The Stranger in Room Six Summary, Characters and Themes

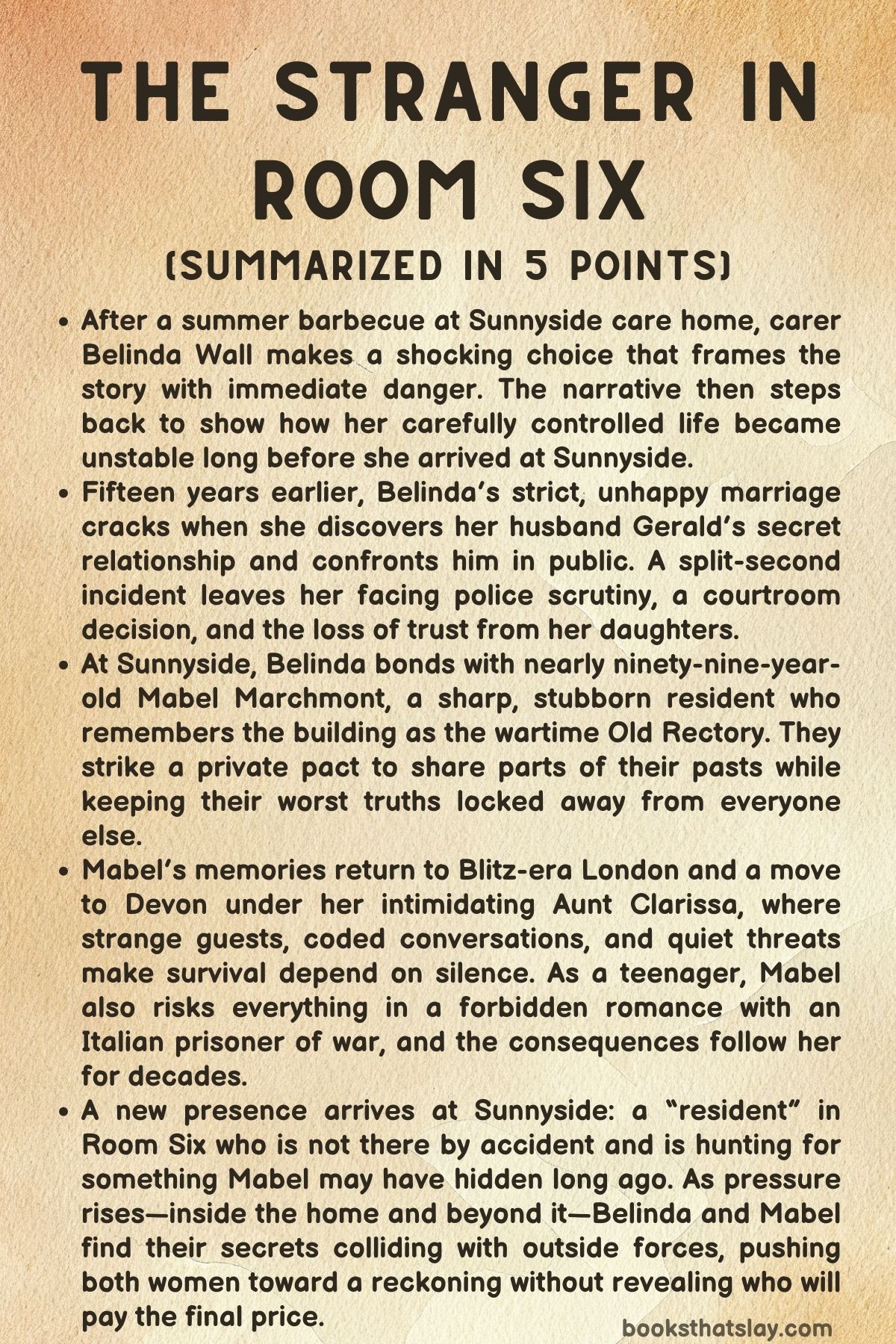

The Stranger in Room Six by Jane Corry is a layered psychological mystery about guilt, secrets, and redemption that unfolds across decades. Set partly in a care home and partly during World War II, the story follows Belinda, a former prisoner hiding her past as a carer, and Mabel, an elderly woman burdened by her own hidden crimes.

When a mysterious stranger arrives with dangerous motives, their worlds collide, revealing long-buried truths about love, betrayal, and identity. Corry constructs a tense narrative that examines how past sins echo into the present, forcing both women to face what they have tried hardest to forget.

Summary

The story opens at Sunnyside Home for the Young at Heart, during a quiet summer evening after a celebration. Carer Belinda is alone in the garden with Mabel Marchmont, an elderly resident in a wheelchair.

As music plays from inside, Belinda realizes the garden is empty and takes out a gun—then fires.

Fifteen years earlier, Belinda Wall lives a dull, suffocating life with her husband Gerald, an accountant obsessed with order. Their marriage lacks affection, held together only for the sake of their daughters.

One morning she receives a letter from Imran Raj, her former lover at Oxford, asking to meet. She hesitates but eventually calls him.

The call goes unanswered, and shortly after, she receives a phone call from a woman accusing Gerald of having an affair with someone named Karen.

Initially dismissing it as a prank, Belinda visits Gerald’s office to deliver his forgotten lunch and finds an unsealed envelope containing a photo of a blonde woman signed “With love, Karen x.” Confronted with evidence of betrayal, Belinda storms out, shaken. When she runs into Gerald on the street, she accuses him.

In the heated confrontation, she pushes him away; he falls, hits his head, and dies instantly. The crowd watches in horror as Karen arrives, screaming accusations.

Belinda is taken into custody and charged with manslaughter. In desperation, she calls Imran for help.

With his assistance, she obtains a lawyer, but despite her claims of an accident, witnesses say she pushed Gerald deliberately. She pleads guilty on legal advice and is sentenced to prison.

Her daughters become distant, and her once-structured world collapses.

The narrative alternates between Belinda’s timeline and Mabel’s memories from the late 1930s and 1940s. As a child in London during the Blitz, Mabel loses her mother and baby sister in a bombing.

She is sent to live with her austere Aunt Clarissa at the Old Rectory in Devon, where she encounters the enigmatic Colonel Dashland. Mabel senses secret wartime activities between her aunt and the Colonel, involving coded conversations and hidden documents.

She befriends Italian prisoner of war Antonio, assigned to work on the estate, and despite knowing the risks, begins a forbidden romance with him.

When Mabel becomes pregnant, Clarissa is furious, fearing scandal. She sends Mabel away under the guise of a holiday.

Mabel is transported to Cornwall, where she stays with two sisters, Beryl and Olive. When she gives birth to a son she names Antonio, Clarissa arranges for the baby to be taken away, cutting Mabel off from him.

The trauma shapes the rest of her life.

In the present day, Mabel lives at Sunnyside Care Home—the very Old Rectory where she spent her wartime years. She is witty but sharp-tongued, and her memory drifts between past and present.

Belinda, now working under a false identity, is assigned as her carer. The two women form a quiet friendship built on shared loneliness and secrecy.

Mabel confides fragments of her past, while Belinda admits to killing her husband accidentally. Each senses the other is hiding more.

Their fragile peace is disturbed when a mysterious new resident, known only as “The Stranger in Room Six,” arrives. This person is in fact an undercover operative sent to retrieve a hidden wartime document linked to Mabel’s past—a confidential list naming Nazi sympathizers in Britain.

As the operative searches Mabel’s room, they find nothing except an old doll, Polly. Suspicion grows, and violence threatens to erupt again.

The story shifts to Belinda’s years in prison. She endures bullying, isolation, and betrayal from fellow inmates.

One cellmate’s suicide and another’s violent attack leave her hardened. She learns that Gerald’s mistress Karen bore his child, confirming the extent of his deception.

Though Imran continues to support her from outside, Belinda’s daughters refuse contact. She emerges from prison a changed woman—bitter, cautious, and consumed by guilt.

Back at Sunnyside, Belinda grows protective of Mabel. But the investigation surrounding Mabel’s wartime activities intensifies.

When Belinda notices an opening seam in Mabel’s cherished doll, she and the authorities discover a hidden document inside—a government list of suspected Nazi collaborators. Shockingly, Mabel’s own name appears.

Terrified, Mabel insists she never knew it existed, suggesting Clarissa must have hidden it. She also reveals another secret: a badge from the British fascist movement that she accidentally kept as a child.

Soon after, Belinda’s past catches up with her. Stephen Greaves, the son of Gerald’s mistress, visits Sunnyside.

He reveals that Gerald was his father and that he died of an undiagnosed heart condition, meaning his fall might not have been the true cause of death. The revelation forces Belinda to confront years of misplaced guilt.

Meanwhile, the exposure of the wartime list causes public outrage. Mabel is accused of treason when photos emerge of her with Antonio, the Italian prisoner, and their baby.

Rioters target Sunnyside, forcing Mabel into hiding. Belinda is accused of leaking the story to a journalist, which Mabel believes at first.

Their friendship fractures.

Later, Belinda finds Mabel’s lost locket at a jeweller’s. Inside it lies a photo labeled “Our darling daughter,” revealing that Clarissa was actually Mabel’s mother, not her aunt.

This changes everything: Clarissa had fabricated the story of adoption to protect Mabel from disgrace. With help from old friends and the press, Mabel’s reputation begins to recover.

An Italian woman named Isabella then contacts Belinda, claiming to be Mabel’s great-granddaughter. She arrives with Mabel’s long-lost son, Antonio, now elderly and suffering from dementia.

The reunion brings peace to Mabel, who travels with them to Italy to live out her remaining days.

Belinda stays on at Sunnyside for a time, eventually forgiving herself and reuniting with Imran. Her daughters begin to reconnect, and she finds a fragile sense of closure.

In her final letter to Belinda, Mabel reveals the last secret she had kept: after the war, Clarissa begged her to end her life, tormented by guilt for aiding a fascist group. Mabel shot her and staged the death as a political killing, hiding the truth for decades.

Mabel’s great-granddaughter later writes a novel inspired by her story, ensuring her hidden life will be remembered.

The Stranger in Room Six ends with echoes of forgiveness and the recognition that both women, haunted by their pasts, finally find release from the secrets that once bound them.

Characters

Belinda Wall

Belinda is the novel’s emotional engine: a woman who looks ordinary from the outside but carries a life shaped by betrayal, shame, and survival. In The Stranger in Room Six, her first defining quality is restraint—she has learned to swallow rage, perform normality, and keep going for the sake of her daughters, even when her marriage to Gerald feels like a cage built from routine and indifference.

That restraint shatters when she discovers evidence of Gerald’s affair, and her impulsive confrontation on the street ends in catastrophe; the death is accidental, but the public nature of it—and the presence of witnesses and Karen—turns the moment into a moral courtroom where Belinda is judged before any verdict is spoken. Her later decision to plead guilty to manslaughter and refuse Imran’s help, even when it could save her, shows how powerfully she is driven by maternal protectiveness and fear of being seen as selfish.

Prison hardens her, not into a villain, but into someone who understands that kindness can be dangerous and that reputation can become a weapon. When she reaches Sunnyside and forms an intense bond with Mabel, Belinda’s caregiving becomes both genuine and strategic: she craves connection and redemption, yet she also needs safety through secrecy.

Her arc is defined by the tension between wanting to be good and needing to survive—so when she is later accused of betrayal at Sunnyside and cast out by Mabel, it hits her at the deepest wound: the terror of being permanently reduced to “what she did” rather than “who she is.” By the end, her reconnection with Imran and her tentative reconnection with family suggest not an easy absolution, but a hard-won permission to live beyond her worst day.

Mabel Marchmont

Mabel is sharp-tongued, funny, and intimidating in old age, but those traits are armor forged in childhood trauma and lifelong secrecy. In The Stranger in Room Six, her memories of the Blitz and the loss of her mother and sister establish a foundational wound: the world can erase people in an instant, and adults can rewrite the truth to suit themselves.

When she is sent to her aunt Clarissa at the Old Rectory, Mabel becomes a child trained in emotional surveillance—watching faces, reading threats, learning what must not be said. That skill becomes her lifelong survival tactic, and it is why she remains so controlling of her own narrative at Sunnyside, refusing memoirs and rationing what she shares even with Belinda.

Her love story with Antonio reveals the younger Mabel’s hunger to be chosen and cherished; the relationship is reckless and tender, and her pregnancy places her at the intersection of wartime hypocrisy, female vulnerability, and social cruelty. Mabel’s later life is haunted by what she hid and what was taken from her, and the plot’s central mystery turns her into both target and gatekeeper.

When the hidden list and political fallout explode, she is forced to experience a second invasion: once again, powerful forces claim ownership of her story and body of evidence, and once again she must fight not just for safety but for meaning. The final confession—that she shot Clarissa at Clarissa’s request and staged the aftermath—reframes Mabel as someone who has carried an unbearable secret not out of malice, but out of a warped form of duty and love shaped by fear.

Her ending, relocating to Italy and being reconnected to lineage through Isabella, gives her what she has been denied since childhood: a family narrative that finally includes her truth.

Gerald Wall

Gerald initially presents as the safe, boring husband—punctual, routine-obsessed, emotionally predictable—but The Stranger in Room Six reveals that his “tidy” personality is a kind of selfishness disguised as stability. His affair is not only sexual betrayal; it is an administrative betrayal, a life managed in compartments where Belinda is kept functioning as wife and mother while he pursues another existence with Karen and fathers a secret child.

The fact that he calls Belinda for forgotten sandwiches right after the accusation lands is especially telling: he treats her as a service he can summon, assuming her compliance is guaranteed. Yet Gerald is not written as purely monstrous; when confronted, he cries and calls it complicated, which suggests either genuine remorse or fear of consequences, and his reported heart condition complicates the moral picture by implying he may have been living with private vulnerability while still choosing deception.

His death becomes the pivot that destroys Belinda’s social identity and detonates the family, and even after he is gone, his hidden choices keep shaping events—through Stephen, through Karen, and through the truth about what he concealed.

Imran Raj

Imran functions as both Belinda’s past and her alternative future in The Stranger in Room Six. He represents a version of Belinda that existed before compromise—Oxford, love, possibility—and his sudden reappearance via the letter jolts her into remembering that she once wanted more than endurance.

When crisis hits, he becomes practical rather than romantic, answering her call from the police station and arranging legal help, which shows that his attachment is not just nostalgia but responsibility. At the same time, Imran is a complicated symbol: Belinda’s daughters immediately suspect him as part of the disaster, and Belinda herself fears that accepting his help will confirm the worst assumptions about her.

His presence therefore intensifies her shame and her maternal guilt, because he embodies what she “owes” her family versus what she might want for herself. Later, when Belinda chooses to leave Sunnyside and live with him, the decision reads less like a fairytale ending and more like Belinda finally permitting herself a life not entirely dictated by punishment.

Karen Greaves

Karen is introduced through accusation and evidence—a voice on the phone, a photograph in an envelope, a scream at the scene of Gerald’s death—so she first appears as threat, disruption, and moral rival. In The Stranger in Room Six, she is also grief in motion: she calls Gerald “the man she loved,” and her reaction positions Belinda as the public villain regardless of legal nuance.

Yet Karen’s later significance deepens when her child with Gerald is revealed, because it makes her less of a simple “other woman” and more of someone who built a parallel family life inside Gerald’s lie. Karen becomes a living consequence of Gerald’s compartmentalization, and her ongoing presence through Stephen keeps Belinda trapped in the afterlife of the marriage.

Even when Belinda later grows calmer around Karen, that calm is hard-earned; it suggests Belinda has moved from rivalry into resignation and, eventually, into a form of empathy for how Gerald’s deceit harmed multiple women at once.

Gillian Wall

Gillian’s role is defined by rupture: she is one of the daughters whose trust collapses under the weight of public scandal, private suspicion, and the humiliations of prison visiting rooms. In The Stranger in Room Six, Gillian’s estrangement illustrates how a child’s love can be overwhelmed by shame and by the fear that a parent’s hidden life might be the real truth.

Her distance also becomes one of Belinda’s punishments more painful than incarceration itself, because it removes Belinda’s main justification for endurance. When Gillian later has a tentative moment of contact, it reads as emotionally realistic rather than tidy—damage does not disappear, but the possibility of repair appears.

Elspeth Wall

Elspeth functions as the daughter who is still wounded but more willing to look directly at complexity. In The Stranger in Room Six, she visits Belinda in prison and delivers devastating updates—about the funeral, the lost home—yet that act of visiting is also a kind of loyalty, even if it is mixed with anger.

Her discovery of Imran’s letter and suspicion of Belinda’s connection to him show how children become investigators when adults’ stories stop making sense. Elspeth’s later refusal to meet Stephen suggests protective boundaries and lingering bitterness, but her eventual encounter with him at Sunnyside implies she is capable of curiosity and growth once the initial shock has settled.

Penny

Penny begins as a small, almost incidental figure—Gerald’s receptionist—but in The Stranger in Room Six she becomes a hinge of revelation. Her early interaction with Belinda at the office keeps Gerald conveniently out of reach, heightening Belinda’s dread, and her later prison visit delivers one of the cruelest truths: the affair produced a secret child.

Penny’s role demonstrates how “minor” witnesses in an ordinary workplace can hold the matches that ignite a life, and her decision to bring information to Belinda suggests either compassion, guilt for what she saw, or a need to unburden herself. Either way, she is a messenger of the real Gerald—an administrator of secrets.

Jac

Jac embodies the violent social ecosystem of prison and the way power is performed through intimidation. In The Stranger in Room Six, her initial friendliness turning into threat after the drug package incident shows how fragile safety is in captivity and how quickly a person can become a target for accidental transgression.

The boiling sugared tea attack is not just brutality; it is symbolic of Jac’s desire to mark Belinda permanently, to brand her as someone who must pay. The fact that Jac ends up scalded instead underscores Belinda’s reluctant transformation—she is not seeking dominance, but she is learning that survival sometimes requires force, and that consequences in such a system are immediate and irreversible.

Clarissa

Clarissa is the architect of Mabel’s fear and the embodiment of social reputation as a weapon. In The Stranger in Room Six, she is cold, controlling, and deeply invested in appearances, reacting to Mabel’s pregnancy not as a family crisis requiring care but as a scandal requiring containment.

Her decision to intercept Mabel’s note to Antonio and report him to be moved away is an act of strategic cruelty disguised as propriety, and it reveals how she uses institutions—family authority, the camp command, community gossip—to control outcomes. Clarissa is also the center of the most haunting moral knot in the book: her later request that Mabel shoot her, and Mabel’s compliance, suggests a relationship where love and damage are inseparable.

Clarissa is not simply villainous; she is a product and producer of wartime paranoia, class preservation, and private desperation, and she leaves Mabel with a lifetime of contaminated loyalty.

Antonio

Antonio is Mabel’s first experience of being seen as desirable and cherished, and his presence disrupts the wartime logic that insists enemies are simple. In The Stranger in Room Six, he is gentle, musical, and politically ironic in the best way: he explains that his family does not support the Germans, which punctures Mabel’s inherited propaganda and allows her to imagine moral complexity.

Their relationship becomes Mabel’s secret refuge—especially the tunnel meetings—and Antonio’s dream of marriage and Italy offers her an escape from Clarissa’s control and from the grief of London. His disappearance from Mabel’s life is therefore not just romantic loss but the theft of an alternative identity.

The later revelation that he drowned after the war, never knowing he had a son, turns him into a tragic emblem of how war doesn’t only kill bodies; it kills futures.

Beryl

Beryl enters Mabel’s life by chance on the train, but in The Stranger in Room Six she becomes the face of ordinary compassion—the kind that shows up without planning and then refuses to leave. Her talkativeness is not trivial; it is protective, a way of keeping fear at bay and drawing Mabel into human warmth when she is most vulnerable.

Beryl’s decision to take responsibility for Mabel after the failed meeting at Penzance demonstrates moral courage, and her loyalty helps create the closest thing Mabel has to a safe maternal presence after her losses. She also serves as emotional bridge to Olive, softening a household defined by grief and tension.

Olive

Olive is stern, capable, and haunted by a past failure that makes her both cautious and intensely determined. In The Stranger in Room Six, her reluctance to accept Mabel at first is not coldness but fear—fear of repeating tragedy, fear of the village, fear of the consequences of childbirth after Kitty’s death.

Yet when labor comes and help is unavailable, Olive becomes steel: she takes charge, uses her training, and delivers the baby. That act is more than medical competence; it is an attempt at redemption, a refusal to let history repeat itself under her roof.

Olive’s insistence that Clarissa has no right to decide the baby must be adopted positions her as an ethical counterweight to Clarissa’s control.

Frannie

Frannie is important because she shows what friendship looks like when it survives time and public pressure. In The Stranger in Room Six, she exists first as a village connection in Mabel’s childhood and later as Dame Frances Buss, someone with enough stature to defend Mabel publicly.

Her defense reframes Mabel not as a willing collaborator but as a manipulated teenager, and that shift matters because it demonstrates how narratives can be corrected when someone credible chooses truth over spectacle. Frannie’s loyalty is the kind that doesn’t just comfort privately—it intervenes publicly, changing outcomes.

Harry

Harry functions as the political and strategic lens through which the wartime list becomes a modern crisis. In The Stranger in Room Six, he is less defined by warmth than by calculation: he wants Belinda close partly to manage risk, he frames the fallout in terms of reputational warfare, and he treats the list as something that can destroy contracts, careers, and alliances.

His role highlights how history is never past when powerful names are involved, and how institutions respond to danger by controlling people—especially vulnerable ones like Mabel—“for their safety,” even when that safety looks like confinement. Harry is not purely antagonistic, but he represents the world that turns human lives into collateral.

Garth

Garth is the operational counterpart to Harry: practical, directive, and focused on retrieval and containment. In The Stranger in Room Six, his handling of the doll and the concealed document shows professional caution and a belief that objects matter more than comfort, even when the object is someone’s cherished possession.

His approach to Mabel after the list is found—restricting movement and warning of retaliation—positions him as someone who deals in worst-case scenarios. Garth embodies the story’s theme that truth can be dangerous not only because it is shameful, but because it threatens powerful networks.

Stephen Greaves

Stephen is the living proof that Gerald’s betrayal had a second, hidden timeline. In The Stranger in Room Six, his confrontation with Belinda is emotionally surgical: he arrives with documents, photos, and a letter, forcing Belinda to look at the full architecture of Gerald’s deception—another child, another love story, and even a concealed heart condition.

Stephen’s resemblance to Gerald adds a psychological sting, making him feel like a ghost made physical. Yet he is not written simply as an avenger; his willingness not to expose Belinda suggests maturity and a desire for understanding rather than punishment.

His wish to meet Belinda’s daughters is less about intrusion than about assembling the truth of his own identity, which Gerald fragmented through secrecy.

Amanda Smith

Amanda represents the machinery of exposure: the modern appetite for scandal and the way information becomes currency. In The Stranger in Room Six, she matters less as a fully intimate personality and more as a force that turns private pain into public entertainment.

The suspicion that Belinda fed her information, and the resulting confrontation, dramatize the moral trap Belinda lives in—wanting control over her story but risking destruction when she tries to shape it. Amanda’s presence reinforces the book’s theme that confession is never just emotional; it is political and economic.

Claudette

Claudette is a sharp illustration of opportunism wrapped in charm. In The Stranger in Room Six, her decision to sell Mabel’s photos to the press is a betrayal that weaponizes intimacy—turning evidence of teenage love and motherhood into ammunition for humiliation.

Her role shows how harm does not always come from grand villains; sometimes it comes from someone close enough to access what’s private and casual enough to treat it as profit. Her suspended sentence and fine also underline the imbalance between legal consequence and emotional devastation.

Isabella

Isabella enters as a sudden bridge between past and future, transforming Mabel’s story from isolated tragedy into lineage. In The Stranger in Room Six, she functions as both descendant and witness: she arrives with the adopted Antonio, offers context that Mabel never had access to, and gives Mabel a chance to be seen not as a scandal but as an ancestor.

Isabella’s presence also reshapes the meaning of secrecy—some truths, when finally placed in the right hands, become healing rather than destructive. By writing a novel based on Mabel’s life after Mabel’s death, Isabella turns trauma into narrative ownership, ensuring that Mabel’s story is no longer controlled by Clarissa’s shame or by public hysteria, but by someone who loves her enough to tell it whole.

Antonio Marchmont

Mabel’s son, also named Antonio, embodies the long-term human cost of Clarissa’s choices and wartime morality. In The Stranger in Room Six, his adoption and later dementia create a painful irony: the child who was once the reason for secrecy becomes an adult who cannot fully receive the truth when it finally surfaces.

His presence validates Mabel’s motherhood—she was not imagining a future; she created one—yet it also confronts her with what was stolen: years of knowing him, raising him, being recognized. Through him, the novel emphasizes that the past does not end when a secret is hidden; it continues in bodies and families across decades.

Themes

Guilt and Moral Responsibility

Throughout The Stranger in Room Six, guilt operates as a central emotional and moral force shaping the lives of both Belinda and Mabel. For Belinda, guilt is both punishment and survival.

Her accidental killing of her husband Gerald is the turning point that defines her existence; the event becomes not just a crime but an identity. Even after serving her sentence, she cannot escape the weight of her actions, forcing her to conceal her past and live under a new name.

Her work at Sunnyside Home, caring for the elderly, is an unconscious act of penance — a way to serve others and regain a sense of moral balance. The novel explores how guilt can metastasize into self-loathing, mistrust, and a relentless search for redemption.

Belinda’s guilt is complicated by the revelation of Gerald’s betrayal and illness, blurring the line between justice and tragedy. In contrast, Mabel’s guilt is buried deep within the corridors of time, tied to wartime secrets and an act of mercy that cost her innocence.

Her memory of shooting Aunt Clarissa — at Clarissa’s desperate request — reveals the moral complexity of survival and compassion during war. The novel suggests that guilt is not always born from wrongdoing but sometimes from acts of necessity or love.

Through both women, the story questions whether confession truly brings peace or whether guilt becomes an inseparable companion, shaping identity and dictating every choice that follows.

Secrets and the Burden of Truth

The narrative of The Stranger in Room Six is built on secrets — personal, familial, and political — that span decades. From Mabel’s concealed wartime pregnancy and hidden documents to Belinda’s buried criminal past, every layer of the story reveals how secrecy corrodes trust and reshapes lives.

Secrets act as both shield and weapon. For Mabel, silence is a means of protection; revealing her relationship with Antonio or her act against Clarissa would have destroyed her in the judgmental society of wartime England.

Yet the cost of such secrecy is lifelong isolation, shame, and a fractured sense of self. Belinda’s forged identity similarly offers safety but robs her of authenticity.

She lives in constant fear of exposure, even as she develops genuine bonds with Mabel and her patients. The care home itself becomes a metaphor for hidden histories — a place where the past is disguised by cheerful facades and routine.

Jane Corry portrays secrecy not simply as deceit but as a necessary survival mechanism in a world that punishes vulnerability. The revelation of the “CONFIDENTIAL” list hidden inside Mabel’s childhood doll underscores the destructive power of withheld truth on both personal and political levels.

The novel ultimately portrays truth as a dangerous freedom — something that can liberate but also devastate, leaving characters to choose between safety in silence and the peril of revelation.

Female Resilience and the Struggle for Independence

The women in The Stranger in Room Six are marked by endurance in the face of betrayal, confinement, and societal judgment. Belinda’s journey from obedient wife to convicted killer to caregiver highlights a woman’s attempt to reclaim agency after being reduced to a label.

Her resilience lies not in defiance but in persistence — the ability to continue living when the world has already condemned her. Mabel’s story, spanning from a sheltered girl to a secret mother and finally a haunted elderly woman, mirrors the constraints placed on women across generations.

Her forced separation from Antonio and the concealment of her child exemplify how patriarchal and moralistic systems sought to control women’s bodies and choices. Yet, despite repression, both women carve out forms of independence.

Their friendship becomes a quiet rebellion — a bond forged outside societal definitions of respectability. Through them, Corry portrays womanhood as a continuum of survival, one that adapts through silence, wit, and endurance.

The novel’s modern and historical timelines together expose the recurring patterns of female constraint and resilience, showing that the battle for autonomy, though fought in different eras, remains essentially the same.

War, Memory, and the Persistence of the Past

The novel’s dual timelines reveal how the traumas of war never truly end; they merely evolve into new forms of conflict. Mabel’s memories of wartime England, the air raids, and her forbidden love with Antonio expose the long-term psychological scars of living through chaos.

Her later life at Sunnyside is dominated by ghosts of that past — both literal and emotional. The Blitz, the moral compromises made for survival, and the enduring silence around collaboration and betrayal form a shadow that extends into the present.

Even Belinda, born decades later, is trapped in a personal war — one of guilt, secrecy, and emotional imprisonment. The discovery of the wartime “list” ties personal memory to collective history, showing how political sins are never fully buried.

Corry suggests that memory, while fragile, is also inescapable; attempts to suppress it only deepen its hold. The transitions between Mabel’s lucid recollections and her present confusion evoke how the past intrudes upon the present with alarming clarity.

The novel’s closing scenes — with Mabel’s confession to her great-granddaughter and Isabella’s decision to write her story — suggest that remembrance is both burden and salvation. Only by confronting history, however painful, can healing begin.

Redemption and Forgiveness

Redemption in The Stranger in Room Six is neither sudden nor absolute; it emerges slowly through empathy and acceptance. Belinda’s path toward forgiveness begins when she starts caring for others, not as a form of martyrdom but as recognition of shared fragility.

Her friendship with Mabel becomes a mirror through which she sees her own guilt in perspective — understanding that everyone carries shadows of regret. The act of returning Mabel’s locket, her attempts to protect her, and her final honesty with her daughters signify small yet profound steps toward redemption.

Mabel’s forgiveness, too, operates on several levels — forgiving her aunt for cruelty rooted in fear, forgiving herself for survival, and ultimately granting Belinda grace despite betrayal. Corry’s portrayal of forgiveness resists sentimentality; it is portrayed as an act of moral courage that does not erase pain but transforms it into understanding.

The final exchange of letters between Mabel and Belinda reflects the human need to be absolved not by divine justice but by another flawed soul who has also suffered. The story closes not with complete peace but with the possibility of it — a recognition that forgiveness, however partial, allows life to continue after devastation.