The Second Chance Cinema Summary, Characters and Themes

The Second Chance Cinema by Thea Weiss is a romance with a touch of magic, built around the idea that our lives have “scenes” we replay—whether we want to or not. Ellie Marshall, a writer known for spotlighting places on the verge of disappearing, is stuck in a creative slump and weighed down by an old loss she never faced head-on.

Her fiancé Drake, steady and routine-loving, wants a calm life that feels safe. Then they find a hidden cinema that seems to screen the most important memories they’ve ever lived, forcing them to decide what they’ll keep carrying—and what they’ll finally say out loud.

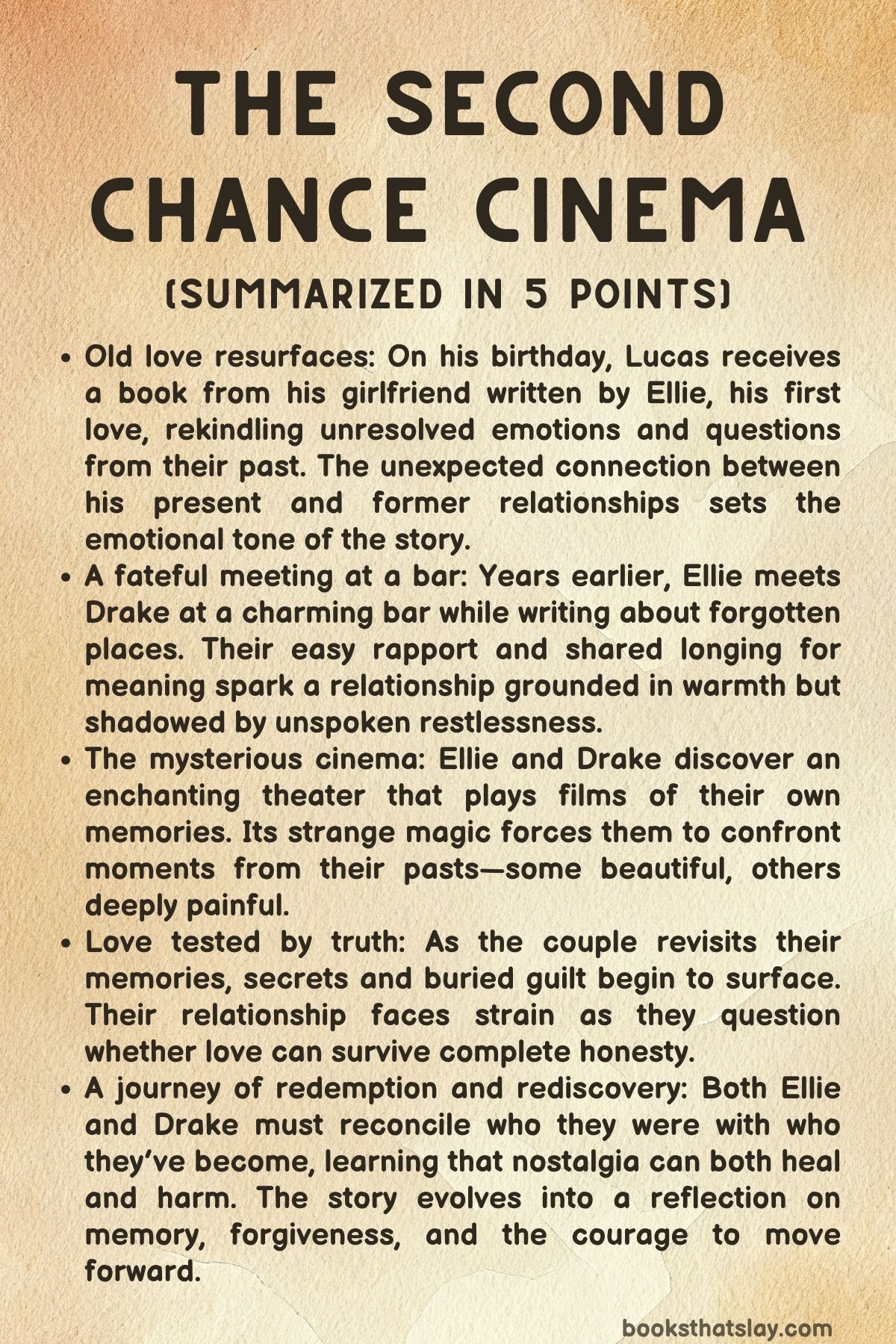

Summary

Lucas, celebrating his birthday with his girlfriend Stephanie, receives a gift that hits like an exposed nerve: a book titled The Compendium of Forgotten Things by Ellie Marshall, his first love. The sight of Ellie’s name snaps open memories he has tried to shelve, including the way she disappeared from his life without closure.

A line in the book about first and second loves feels aimed directly at him, and even though he keeps his reaction contained, the moment makes it clear that Ellie still leaves a mark.

Years earlier, Ellie steps into a dim, cozy bar called Finn’s with a plan to write about it for her series on overlooked places. She’s drawn to its warmth, the jazz, the sense that it holds stories people forgot to tell.

Sitting at the bar, she meets Drake, a kind, grounded man who doesn’t match her usual pattern of messy, unreliable dates. They talk easily.

Ellie explains her work and her obsession with saving vanishing corners of the world by writing them into permanence. Drake admits he’s a creature of habit who builds identical houses for a living, even though he wants to create spaces that matter.

Their connection forms quickly—rainy walk home, a borrowed jacket, exchanged numbers—and soon they’re dating.

Two and a half years into their relationship, Ellie’s career no longer feels secure. Her agent Nolan tells her the spark in her writing is fading; her newer work isn’t landing the way it used to, especially compared to the piece about Finn’s that launched her into public attention.

Small humiliations pile up, like discovering a bookstore no longer carries her book and hearing a clerk dismiss it as “clutter.” Ellie returns home to Drake, who’s absorbed in turning their Queen Anne–style house into a calm domestic nest. He loves her, but he also loves routine, and Ellie can feel herself tightening inside the predictability.

On a night out, Drake tries to cheer her up with a customized Nancy Drew-style book that retells how they met, and for a moment it works—until Ellie’s itch for something different returns.

After dinner, Ellie pushes Drake to wander the city instead of going straight home. They stumble upon a brick archway that leads to a lane that doesn’t seem to belong to the modern world: pastel storefronts, gas lamps, and an ornate old cinema playing a film called The Story of You.

Drake is wary, but Ellie is curious in the way she always is with disappearing places. Inside, they buy ten-entry ticket spools from a teenage clerk.

The theater is lavish and strangely intimate, and a cartoon warning suggests the movie will stop if they try to leave or record it. Then the film begins by showing Drake’s earliest memories—birthday scenes, family moments—followed by Ellie’s childhood with her brother Ben.

It’s not a documentary; it’s their lives. Ellie is stunned and drawn in.

Drake panics, yanking her out as if leaving can make it unreal.

Back home Drake searches online for evidence the cinema exists and finds nothing. He wants to forget it, calling it dangerous.

Ellie insists it was real, and she becomes determined to return—partly because it mirrors her life’s work, and partly because she suspects it can show her something she has never fully remembered from her past. She’s been living for years under a heavy guilt connected to Ben, convinced she caused something terrible.

The cinema feels like a way to finally know the truth.

Their lives continue in uneasy parallel: an engagement party thrown by Ellie’s mother Sandra, who values appearances over closeness; Ellie’s simmering resentment; Drake’s ability to charm people even when Ellie feels exposed and judged. Ellie and Drake’s conflict isn’t loud yet, but it’s there—Ellie wanting change, Drake wanting stability, both pretending the gap isn’t widening.

One Saturday, instead of returning to the cinema as Ellie planned, they play Scrabble with friends Jen and Marc. Jen is pregnant and nostalgic for the chaos and stories of earlier years.

Ellie, restless, impulsively invites them along anyway, hoping that bringing “backup” will force Drake to stop resisting. When they arrive, Ellie is horrified to find the cinema boarded up and ruined, covered in dust and graffiti, like it has been dead for decades.

Drake uses it as proof the whole thing was imagined. But when Ellie drags him back minutes later, the building has restored itself—lights glowing, chandelier shining, marquee alive again.

The ticket clerk appears and tells them the film is only for them. Drake is shaken by the impossibility, and Ellie realizes the cinema can change its face depending on who is looking and why.

Ellie convinces Drake to return under strict rules: they only go together, they tell no one, Ellie cannot write about it, and they will still marry. When they meet the manager Natalie, she confirms the cinema’s power without explaining it, framing the experience as something you accept rather than solve.

Each ticket corresponds to a themed screening built from their most “cinematic” memories—the moments that shaped them.

They watch “School,” seeing Drake’s kindness and early humiliations, and Ellie’s bond with Ben as he rescues her from a miserable day and gives her a taste of freedom that becomes part of her identity. They watch “Teenagers,” where Drake has a tender dance connection with an older girl, and Ellie and Ben explore an abandoned mansion with dates, swapping ghost stories and dancing to music that makes the night feel endless.

The screenings bring them closer in one way, but they also expose raw nerves. Natalie’s “lost and found” case holds objects from their lives, including a label that hints at Ellie’s buried trauma, confirming Ellie’s fear that the cinema is leading them toward the memory she’s avoided.

Outside the theater, real life presses in. Ellie receives a message from her estranged father inviting them for Thanksgiving, and the trip is awkward but meaningful.

Ellie finds her own book on his shelf, worn and annotated, and realizes he has been quietly trying to reconnect. The visit leaves Ellie with complicated hope—proof that people can change, but also proof that silence can stretch for years.

When the cinema finally shows the night Ben died, Ellie is forced to watch what she has tried to block out. She called Ben to pick her up from a bad date.

They laughed, ate fries, talked about his future, and at a red light they were struck by another car. Ellie survived; Ben did not.

His last words, “Don’t forget me,” live inside her like a command and a wound. Ellie has carried the belief that her emotion, her words, her presence caused the crash.

Drake follows her outside and holds her through the collapse, telling her the blame belongs to the driver who ran the light, not to her grief and love.

The cinema doesn’t stop there. It also exposes a second kind of pain: jealousy and distrust.

Ellie discovers evidence that Drake’s relationship with his ex, Melinda, was deeper than he admitted. Drake, in turn, is unsettled by Ellie’s long history of leaving lovers behind, afraid she will do the same to him.

Their arguments escalate—about truth, about the way Ellie writes real people into stories, about whether Drake is repeating old romantic habits because they feel safe. Ellie storms out.

Drake smashes a keepsake tied to Melinda and spirals back toward his hometown, where a conversation with Melinda’s husband and his own parents forces him to see how fear has shaped his life.

A hospital waiting room and the birth of Jen and Marc’s baby pull them back into the same space. In the presence of new life, they apologize with fewer defenses.

They decide to stop hiding behind rules and half-truths. Drake brings Ellie to Ben’s grave and gathers her fractured family there, creating a moment where Ellie can finally speak, remember, and mourn without punishing herself.

Healing doesn’t erase the loss, but it changes how she carries it.

Ellie’s career turns again when she lands a new opportunity, and she and Drake rebuild their home and their holiday with intention rather than habit. They return to the cinema for a final screening that reveals the full truth of the night they met—the messy, human details they left out of their romantic origin story.

Instead of destroying them, the honesty steadies them. Drake takes a preserved red rose from the cinema’s lost and found and gives it to Ellie, choosing a new symbol that belongs to them now.

By summer, they marry surrounded by friends and family, honoring Ben’s place in Ellie’s life while choosing to stop living inside old scenes. The story closes with Ellie and Drake committing to the present—not perfect, not polished, but real and shared.

Characters

Ellie Marshall

Ellie Marshall is a complex and deeply introspective character, shaped by her past experiences and internal struggles. As a writer, she initially gains fame with her heartfelt story about a bar, Finn’s, which captivates readers by preserving the memory of a fading gem.

Over the years, her career stalls, and her creative spark dims, revealing her vulnerability. Ellie is also burdened by guilt over her brother Ben’s death, a tragedy tied to a painful memory she has repressed for years.

She constantly seeks meaning and self-discovery, not just through her work but also by revisiting her past, especially her unresolved feelings for Drake and the trauma surrounding her brother’s death. Ellie’s relationship with Drake is a central focus of her emotional journey, filled with moments of nostalgia, jealousy, and the need for reassurance.

She is a woman caught between her yearning for the past and her desire to create a better future, and her emotional depth makes her both relatable and tragic at times.

Drake

Drake is a steady and somewhat reserved character, in contrast to Ellie’s more volatile and emotionally charged nature. His life revolves around stability, routine, and a quiet, somewhat predictable lifestyle.

Drake’s career as a project manager for new homes reflects his desire for order and consistency, yet he longs for something more meaningful. This yearning is amplified by his relationship with Ellie, who challenges him to break free from his comfort zone and confront unresolved issues from his past, particularly his previous relationship with Melinda.

Drake’s internal conflict arises from his fear of repeating old mistakes and his struggle to define his identity outside of the shadows of past relationships. Despite his hesitations, Drake is deeply in love with Ellie and desires to build a future with her, yet his insecurities—especially related to his past with Melinda—threaten the stability he craves.

His journey is one of self-discovery and reconciliation, as he learns to embrace both his past and present to move forward with Ellie.

Stephanie

Stephanie, Lucas’s girlfriend, plays a minor yet significant role in the story. Her presence contrasts sharply with Ellie’s, as she represents stability and the present.

While Lucas is emotionally unsettled by his past with Ellie, Stephanie seems more grounded in their current relationship. Her gift to Lucas, the book The Compendium of Forgotten Things, which was written by Ellie, serves as a catalyst for Lucas’s emotional turmoil.

While Stephanie’s character is not explored deeply in terms of her inner conflict, she serves as a reminder of the challenges of navigating past and present relationships, as well as the complexities that arise when unresolved emotions resurface.

Ben

Ben, Ellie’s brother, is a pivotal figure in her emotional development, even though his presence is largely through memories and the trauma surrounding his death. His death in a car accident, which Ellie feels responsible for, casts a long shadow over her life.

The guilt Ellie carries regarding Ben’s passing shapes much of her actions and emotional state, even though she has buried these feelings for years. Through the cinema, Ellie is forced to confront her repressed memories, and Ben’s role in her past becomes a powerful motivator for her journey toward healing.

Ben represents both Ellie’s lost innocence and the deep-seated grief she has not fully processed, and his impact on her life is felt throughout the narrative, especially as she comes to terms with her feelings of guilt and loss.

Sandra

Sandra, Ellie’s estranged mother, represents the strained relationship between Ellie and her family. She is more concerned with appearances than with fostering genuine emotional connections, which frustrates Ellie.

Sandra’s cold demeanor and preference for social status over personal bonds cause significant tension, especially when she introduces Drake dismissively at the engagement party. Despite this, Sandra’s actions are not entirely devoid of warmth, and she shows moments of pride for Ellie, even if these are often tinged with superficiality.

Ellie’s interactions with Sandra highlight her feelings of inadequacy and abandonment, as she struggles to reconcile her need for maternal approval with the reality of their fractured relationship.

Nolan

Nolan, Ellie’s agent, represents the pressures of the writing industry and the personal doubts that come with it. His critique of Ellie’s work—especially her more recent writing—feeds into her insecurities about her creative abilities.

Nolan’s role in the story is largely that of a professional figure, but his comments about Ellie’s lost spark and fading career serve as a mirror to her internal crisis. He adds to Ellie’s sense of failure, intensifying her longing for something to reignite her creative passion and personal fulfillment.

While Nolan is not a central character, his role highlights the external pressures that Ellie faces as she grapples with her sense of identity and self-worth.

Natalie

Natalie, the manager of the mysterious cinema, is an enigmatic figure who offers crucial insights into the cinema’s magical, memory-altering nature. She serves as a guide for Ellie and Drake, explaining the rules of the cinema while remaining elusive about its true nature.

Her eccentric personality and confident demeanor suggest that she is well-versed in the theater’s strange workings, though she refrains from delving too deeply into its origins or mechanics. Natalie’s role is pivotal in pushing Ellie and Drake to confront their pasts, but her own motivations and backstory remain shrouded in mystery, adding to the film’s otherworldly atmosphere.

She acts as both a catalyst for Ellie’s exploration of her past and a reminder that some things, particularly memories, may be too dangerous to fully understand.

Melinda

Melinda, Drake’s ex-girlfriend, plays a subtle yet significant role in the narrative, acting as a point of comparison for Ellie. She embodies the kind of uncomplicated, easy love that Ellie feels she can never offer Drake.

Through the memories revealed at the cinema, we learn that Melinda and Drake’s relationship was deep but ultimately lacked the excitement and complexity that Ellie brings into his life. Melinda’s desire for stability and her decision not to have children contrast sharply with Ellie’s emotional tumult and creative passion.

Despite the lingering jealousy Ellie feels toward Melinda, it becomes clear that Drake’s relationship with her was part of his journey toward realizing what he truly needs in a partner—something that Ellie offers, even if it means confronting past insecurities and fears.

Jen

Jen is Ellie’s close friend, a lively and pregnant woman who contrasts with Ellie’s introspective and often restless nature. Jen’s contentment with her life and the imminent arrival of her child highlight Ellie’s own sense of longing and dissatisfaction.

Jen’s friendship with Ellie provides a grounding force, offering both support and moments of levity. Her easygoing demeanor offers a stark contrast to the emotional turbulence Ellie experiences, but Jen’s presence helps Ellie navigate her personal challenges, providing comfort when needed most.

Jen’s role serves as a reminder that not all journeys need to be filled with dramatic revelations or trauma—some lives are content with simplicity, and this offers Ellie a glimpse of what peace might look like in her own life.

Themes

Memory and the Persistence of the Past

In The Second Chance Cinema, memory operates as both a haunting and healing force. The narrative repeatedly returns to the question of how the past shapes identity and whether revisiting it can bring peace or paralysis.

Ellie’s obsession with the mysterious cinema—where films replay moments from her and Drake’s lives—embodies the human impulse to revisit what’s lost and understand it anew. The screenings project not just nostalgia but confrontation, forcing Ellie and Drake to face truths they’ve hidden from themselves.

For Ellie, the cinema becomes an emotional archive where her guilt over her brother Ben’s death resurfaces. The act of rewatching her life translates into both punishment and redemption, illustrating how memory is never static—it evolves as understanding deepens.

Even Drake’s encounters with his past loves and family memories underscore the fragility of perception; recollection is revealed as selective and self-serving. The filmic motif emphasizes the constructed nature of memory—edited, curated, and sometimes unreliable—yet vital for reconciliation with oneself.

By the novel’s end, Ellie learns to stop reliving her life through the screen and begins living beyond it, suggesting that true healing lies not in remembering perfectly but in accepting imperfection. The cinema, thus, stands as a metaphor for the mind’s projection room, where what we choose to replay determines whether we remain trapped or move forward.

Guilt, Grief, and the Search for Forgiveness

Ellie’s emotional arc throughout The Second Chance Cinema is driven by guilt, which has long overshadowed her relationships, creativity, and sense of self-worth. Her brother Ben’s death is the defining event of her life, and her belief that she caused the accident has led her to suppress her grief under layers of distraction—career ambition, romantic escapism, and self-sabotage.

When the cinema replays that night, Ellie is forced to confront her guilt in its rawest form, stripped of denial or rationalization. The scene’s visceral detail—the flashing red light, Ben’s laughter, the impact—transforms guilt into a living presence that demands acknowledgment.

This confrontation not only reawakens her mourning but exposes how her inability to forgive herself has corroded her capacity for intimacy. Drake’s compassion becomes the counterforce to her self-punishment; his insistence that she isn’t to blame offers an external grace Ellie struggles to grant herself.

Forgiveness, in this sense, emerges as both a personal and relational act—it must come from within but is sustained by others’ empathy. By visiting Ben’s grave and finally speaking openly with her family, Ellie performs a symbolic act of release.

Weiss positions forgiveness not as the erasure of wrongdoing but as the courage to face memory without flinching. The theme thus intertwines moral reckoning with emotional rebirth, illustrating how grief, when fully acknowledged, can evolve into gratitude and peace.

Love, Imperfection, and the Fear of Repetition

Romantic love in The Second Chance Cinema is portrayed not as a cure for personal wounds but as a mirror reflecting them. The relationship between Ellie and Drake oscillates between passion and tension, built on both affection and unresolved insecurities.

Their love story questions whether two flawed individuals can truly start anew or whether every romance carries echoes of the ones before. Drake’s lingering attachment to Melinda and his habit of recreating gestures from that past relationship embody his fear of change and desire for control.

Ellie, in turn, fears becoming just another chapter in someone else’s story, haunted by her own tendency to leave before being left. Their arguments expose the danger of projecting the past onto the present—each partner reading the other through an old script.

Yet, as the cinema reveals their intertwined histories and vulnerabilities, love evolves from performance to understanding. Their final union—marked by honesty, forgiveness, and shared grief—signals a mature recognition that love must accommodate imperfection rather than idealize it.

Weiss suggests that intimacy requires surrendering to uncertainty, accepting that repetition is inevitable but renewal is possible. The novel’s closing image of their wedding film symbolizes this truth: they no longer need the cinema to validate their love, for they have learned to live unscripted, aware that love’s authenticity lies not in perfection but persistence.

Art, Creativity, and the Fear of Obsolescence

Ellie’s journey as a writer parallels her emotional struggle with loss and relevance. At the story’s start, she faces creative decline—her agent criticizes her work as lifeless, and even bookstores discard her books in favor of minimalist trends.

This professional crisis mirrors her inner stagnation, suggesting that creative vitality is inseparable from emotional authenticity. The cinema becomes a symbolic workshop for rediscovering inspiration; by reliving her memories, Ellie rediscovers the intensity that once fueled her writing.

However, Weiss warns against art that exploits pain without understanding it. Ellie’s past tendency to fictionalize people for her stories echoes her difficulty distinguishing between empathy and self-expression.

As she re-engages with her memories truthfully, her art regains sincerity—culminating in her new TV opportunity, which signifies not fame regained but integrity restored. The novel thus treats creativity as a moral practice, one that demands honesty with oneself and others.

The fear of obsolescence—whether in art, relationships, or identity—is shown to stem from disconnection, not aging or failure. Through Ellie’s renewal, Weiss celebrates art’s redemptive potential while emphasizing that it must evolve with the artist’s emotional truth.

The cinema, once a place of nostalgia, transforms into a metaphor for the creative process itself: revisiting, re-editing, and finally choosing to stop watching and start living.

The Power of Reconciliation and Second Chances

Every thread in The Second Chance Cinema leads toward reconciliation—not only between Ellie and Drake but within families, with the past, and with oneself. The title encapsulates this redemptive ethos: life constantly offers opportunities to revise what once felt final.

Ellie’s strained relationships—with her parents, her late brother, and even her younger self—illustrate how distance and misunderstanding often mask enduring love. Her father’s quiet annotations in her book and her mother’s eventual gift of Ben’s jacket demonstrate that reconciliation need not erase conflict; it thrives on recognition and acceptance.

Similarly, Drake’s journey back to his hometown and conversation with Melinda’s husband reframe regret as wisdom, not defeat. The novel suggests that healing is rarely grand—it unfolds through small gestures, shared silences, and renewed courage to connect.

The final decision of Ellie and Drake to stop watching the films of their lives and instead live them underscores the culmination of this theme. They move from spectators to participants, acknowledging that while the past cannot be changed, the present can always be re-chosen.

Weiss thus portrays second chances not as miracles but as deliberate acts of forgiveness and faith—the willingness to love again, remember without pain, and keep creating meaning even after loss.