The Ten Year Affair Summary, Characters and Themes

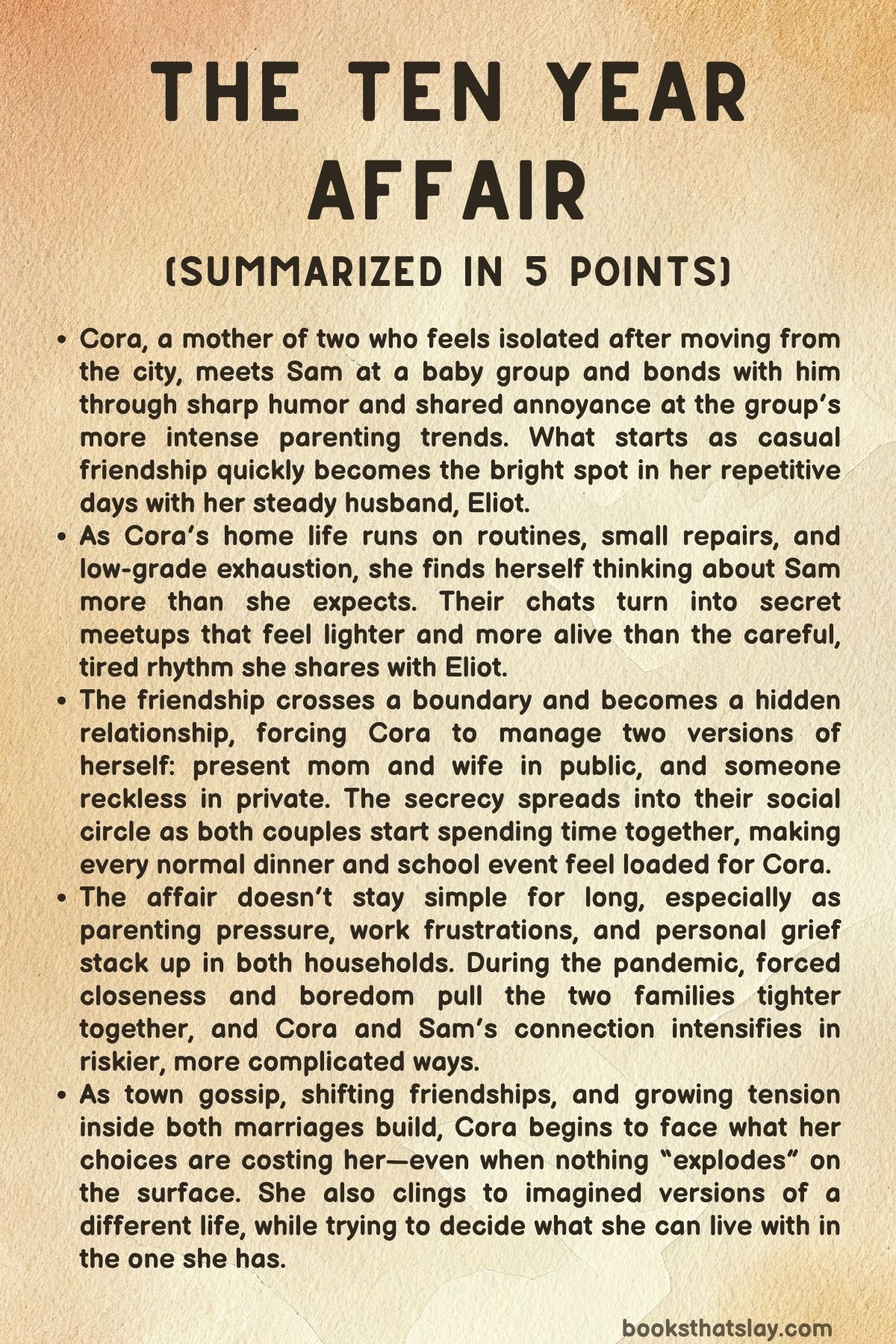

The Ten Year Affair by Erin Somers is a sharply observed exploration of modern marriage, desire, and the quiet restlessness that lingers beneath domestic life. The novel follows Cora, a woman juggling motherhood, work, and a marriage that has settled into routine.

When she meets Sam, another parent in her small town, their friendship gradually turns into an affair that spans years, transforming both of their lives and the families entangled with them. Through humor and unease, Somers examines the contradictions of middle age—love and betrayal, freedom and confinement, the allure of transgression and the comfort of stability.

Summary

Cora’s life revolves around her husband Eliot and their two children, Opal and Miles. Having recently moved from the city to a small town after inheriting her father’s money, she struggles with isolation and the monotony of domestic life.

At a baby group, she meets Sam, another new parent whose sarcasm and cynicism match her own. Their first connection forms when they mock another mother’s extreme parenting tactics, and soon they exchange numbers.

What begins as casual friendship evolves into something deeper—Cora feels drawn to Sam’s easy humor and the sense of possibility he represents, a contrast to her predictable marriage with Eliot.

At home, Eliot is kind and stable, but detached. He smokes weed on the porch while Cora recounts her days, their conversations laced with fatigue.

Their home is a work in progress—faulty appliances, a mysterious bathroom mushroom—that mirrors the imperfections in their marriage. Cora begins waiting for accidental meetings with Sam, craving the spark he brings into her dull routines.

When she finally sees him again, they share a drink after baby group, laughing over the absurdity of suburban life. The attraction between them grows undeniable, and a brief, impulsive kiss marks the beginning of their affair.

At first, their connection feels like a harmless escape. They meet secretly in bars and cars, telling themselves it’s just friendship.

But soon they sleep together, and Cora finds herself living two lives—devoted mother and reckless lover. She fabricates stories about a fictional coworker named Morgan to cover her absences.

Eliot remains unsuspecting, focused on work and childcare. The deception becomes second nature to Cora, who feels both liberated and guilty.

When the two couples start socializing—Eliot and Cora with Sam and his wife Jules—the situation grows more surreal. They share dinners and PTA meetings, pretending to be ordinary friends while hiding an explosive secret.

The affair intensifies but also brings unease. When Cora accidentally becomes pregnant, she and Sam decide on an abortion to preserve their families, but the choice leaves emotional scars.

Their once thrilling connection turns heavy with grief and guilt. Meanwhile, Eliot sinks into depression after his parents’ deaths, further isolating Cora.

She tries to manage the household while maintaining the illusion of normalcy. Though she attempts to end things with Sam, he reacts with anger and desperation, revealing how dependent they’ve become on each other’s chaos.

A shared family vacation to Cape Cod temporarily rekindles their intimacy. On the beach, surrounded by their children, Cora and Sam sneak away to swim naked, clinging to the illusion of freedom.

But when Jules begins to suspect her husband, Cora insists they stop before everything collapses. She deletes Sam’s number and focuses on rebuilding her marriage.

For a time, life steadies—until the pandemic hits. Lockdowns confine both families to their homes, and isolation reignites the affair.

Cora and Sam meet under the guise of shared childcare, resuming their relationship with renewed intensity. They experiment sexually, travel recklessly, and indulge fantasies that blur the line between passion and despair.

Their connection, once exciting, becomes a compulsive escape from the numbness of suburban survival.

When restrictions lift, life resumes its slow rhythm. Sam buys an old yellow Mercedes, a symbolic “project” that never quite works, reflecting his own stagnation.

Jules grows frustrated with his lack of ambition, while Eliot and Cora attempt to repair their fractured intimacy. New neighbors, Richard and Celeste, enter their social circle, bringing flirtation and gossip.

Rumors of infidelity ripple through the town, and Cora’s hidden affair begins to mirror the very scandals she laughs about.

Cora’s career disappoints her—she’s passed over for a promotion due to assumptions about her family obligations. Her resentment deepens as her domestic and professional worlds feel equally limiting.

Jules confides in her about her own potential affair, hinting that marriage itself might be an endless cycle of betrayal and forgiveness. Cora and Sam continue meeting, their encounters increasingly mechanical and joyless.

What once felt like rebellion now feels like repetition.

At a lavish joint birthday party for Eliot and Sam, hosted by Jules and Cora, long-simmering tensions surface. Amid drinking, drugs, and dancing, Cora and Sam finally have sex again—furtive and desperate—in an upstairs guest room.

The act reignites their secret, but guilt quickly follows. Sam later claims it was a mistake, while Cora demands honesty.

Their affair resumes once more, though it’s clear both are exhausted by its weight.

Time passes. Cora and Eliot debate having another child, symbolizing her longing for renewal and his desire to hold onto family life.

On a cruise, she meets an older woman who tells her marriage is a form of captivity, a truth Cora recognizes but can’t fully accept. Back home, she continues balancing her job, parenting, and her clandestine relationship with Sam.

Their meetings at hotels grow increasingly routine. When gossip spreads that Sam is having an affair, the rumor ironically shields Cora, as suspicion falls on others—including Jules.

Jules and Cora eventually clash at book club, their simmering hostility erupting into a physical scuffle. Later, Cora and Sam’s affair unravels for good.

She learns that Jules had known all along and perhaps even had her own indiscretions. Sam and Jules move to California, ending the entanglement that defined Cora’s decade.

She watches their farewell party from a distance, standing beside Eliot, quietly choosing the life she once tried to escape.

Years later, Sam briefly reappears, claiming he still loves her and wants to start over. Cora refuses, finally accepting the ordinariness she once feared.

In the closing scene, she stands in her yard as her daughter calls her inside, noticing a bird take flight above her—a fleeting reminder that beauty and confinement coexist. The novel ends where it began: in the small, imperfect world of family, where the extraordinary hides within the everyday.

Characters

Cora

Cora is the engine of The Ten Year Affair, a woman whose identity is split between the visible competence of motherhood and the invisible hunger for intensity. On the surface, she is a capable parent and professional who can manage logistics, small-town routines, and the everyday humiliations of a house that keeps breaking in petty, symbolic ways.

Underneath, she carries a chronic loneliness that predates the affair, sharpened by her move from the city, her inherited money, and the way domestic life turns time into a loop. Her humor functions as armor: she uses sarcasm to bond, to deflect exhaustion, and to soften the ache of wanting more than she feels allowed to want.

The affair doesn’t create her dissatisfaction so much as give it a shape, and once she experiences a version of herself that feels desired, reckless, and unburdened, she becomes addicted to that contrast. Her moral compromise is not naïve; she knows the cost, but she repeatedly chooses immediacy over stability, partly because stability already feels like a slow disappearance.

Even when she tries to end things, she is pulled back by the fear of going numb again, and by the way secrecy gives her life a pulse. Over time, her emotional arc shifts from thrill to maintenance, from transgression as escape to transgression as habit, until the affair begins to mirror the very stagnation she once used it to flee.

Sam

Sam is charismatic in a way that reads as both playful and evasive, the kind of person who can turn cynicism into charm and anxiety into jokes. In The Ten Year Affair, he initially appears as a lifeline for Cora: someone fluent in irony, quick to mock the absurdities of parenting culture, and willing to step outside the polite scripts of small-town adulthood.

But his appeal is inseparable from his restlessness. He wants to be seen as a good father and husband while simultaneously resenting the responsibilities that make those roles real.

His career identity, with its performative “storytelling” vibe and later job pivots, reflects a deeper pattern: he reinvents narratives about himself faster than he commits to consequences. In the affair, he oscillates between moral handwringing and impulsive pursuit, and that wavering becomes part of the dynamic—Cora pushes for honesty of desire, while he clings to the comfort of ambivalence.

His volatility during the attempted breakup, his need to keep the connection even when it hurts, and his later reappearance with declarations of love suggest a man who confuses intensity with destiny. He is not simply a seducer; he is someone who wants permission to be uncontained, and the affair becomes the place where he can act like the person he imagines himself to be, without paying the full price until reality forces the bill into view.

Eliot

Eliot is steadiness with hairline fractures, the dependable spouse who keeps the household moving but gradually withdraws from intimacy as the years accumulate. In The Ten Year Affair, his practicality is both a stabilizing force and a quiet emotional limitation: he offers Cora safety, routine, and a workable partnership, yet he often meets her restlessness with logistics rather than recognition.

His marijuana use and his tendency to drift onto the porch signal a coping style built on retreat, not confrontation. When grief hits—especially the death of his parents—his depression becomes a physical atmosphere in the house, and he turns inward so completely that Cora is left to carry not only parenting but also the emotional labor of pretending things are fine.

His medication-induced loss of desire deepens the marital distance, and the absence of sex becomes symbolic: not just a missing act, but a missing language of closeness. Eliot is not portrayed as cruel; if anything, his tragedy is how ordinary his unraveling is, how easily sadness becomes a lifestyle.

His small acts of control or punishment, like pushing Cora into cocaine at the party, reveal a submerged resentment and a need to reassert power when he feels sidelined. Yet he also represents endurance—the kind of love that stays, even if it can’t always reach.

Jules

Jules is competence sharpened into resentment, a woman who has built real authority in her career and expects adulthood to be met with reciprocal effort. In The Ten Year Affair, she appears both as a foil to Cora and as her uncomfortable mirror: similarly exhausted, similarly trapped in the optics of good parenting and stable marriage, but more willing to articulate her disappointment.

Her frustration with Sam’s lack of direction isn’t only about money or status; it’s about carrying the invisible weight of planning, worrying, and performing functionality while living with someone who treats life like an improvisation. Her relationship to fidelity is complex: she hints at emotional detachment from the idea of monogamy, admits her own blurred boundaries, and eventually suggests arrangements that complicate the story’s moral binaries.

At book club, her hostility toward Cora reads like social conflict, but it also feels like an instinctive defense of territory—she senses disruption before she has proof, and she reacts with the bluntness of someone tired of being managed or gaslit. Even her public unraveling at the birthday party carries a kind of honesty: she refuses to keep everything pretty.

By the end, her calm acknowledgment that she knew, and her ability to exit without theatrical revenge, makes her one of the most psychologically formidable figures in the book—less a victim than a person who adapts, protects herself, and chooses the terms of her own survival.

Opal

Opal functions as a moral pressure point in The Ten Year Affair, not because she knows the truth, but because childhood perception makes adult deception feel louder. As a toddler she asks about death, forcing Cora to confront what she can’t explain cleanly, and as an older child she becomes part of the rumor ecosystem that threatens to expose the affair.

Opal’s development across the story marks the passage of time more painfully than any calendar: her growing awareness mirrors the way consequences mature in the background. Her social conflicts, including being mean to Jack, also reflect how adult tensions bleed into children’s worlds in distorted forms.

Opal doesn’t exist as a symbol only of innocence; she’s also a reminder that children are active participants in family systems, absorbing tone, stress, and silence even when they don’t understand the plot.

Miles

Miles is quieter on the page, but his presence in The Ten Year Affair intensifies the stakes of every adult decision. As an infant, he anchors the early scenes in bodily reality—sleep deprivation, postpartum storytelling, the relentless demands that shrink personal identity.

Later, as he grows, he represents the continuity of family life that keeps moving regardless of betrayal or grief. Miles is part of what makes the affair possible and unbearable at the same time: he provides the cover of routine, and he embodies the cost of shattering it.

Jack

Jack is a child caught in the crossfire of adult secrecy, small-town surveillance, and children’s gossip. In The Ten Year Affair, his crush on Opal becomes a seemingly trivial conflict that escalates into social friction between Cora and Jules, illustrating how parental anxieties often disguise deeper fears.

Jack also becomes a pivot for rumor—his father is the one people suspect, which turns Jack’s family life into town currency. He is important less for individual agency and more for what his role shows: that in tight communities, children become conduits through which adult narratives spread and mutate.

Victoria

Victoria, the “Broccoli Mom,” is comic on the surface and chilling underneath, a figure whose earnestness becomes its own kind of aggression. In The Ten Year Affair, she begins as an object of shared mockery—broccoli preaching, elimination communication, the performance of superior parenting—but later reappears as a leader of “Pandemic Parenting” ideology, showing how control can dress itself up as optimism.

She functions as a social mirror for Cora and Sam: their contempt for her is partly self-protection, a way to insist they are different from the anxious, performative morality she represents. Yet her return during the pandemic highlights an uncomfortable truth: everyone is constructing narratives to justify how they live, and Victoria simply does it loudly and without irony.

Isabelle

Isabelle represents the city past and the self Cora might have been if she hadn’t settled into suburban ownership and parental routine. In The Ten Year Affair, her visit punctures Cora’s carefully managed normalcy by introducing an outsider’s gaze—someone who can see both the pride and the confinement in Cora’s life.

Isabelle’s warning about Sam carries the weight of an old friend who recognizes danger patterns, and her role emphasizes that Cora’s choices are not inevitable; they are decisions made in a particular emotional climate. Isabelle is also a reminder that friendship can be a moral mirror, even when the person holding it can’t change what they see.

Klaus

Klaus appears as a minor figure, but he matters because he shows what Eliot’s outside world looks like: small, male, and emotionally contained. In The Ten Year Affair, the mention of Klaus as a racquetball friend underscores how Eliot’s life is structured around manageable outlets rather than deep intimacy.

Klaus’s presence also gives Cora an opening to lie about her own social plans, illustrating how easily small marriages develop parallel tracks of assumed trust and unasked questions.

Richard Hood

Richard is predation disguised as neighborly charm, the kind of man who tests boundaries to see what the room will tolerate. In The Ten Year Affair, his flirtation escalates into flashing, and he uses social settings—dinners, dancing, jokes—to keep his behavior deniable while still forcing Cora to carry discomfort privately.

His presence intensifies the book’s theme of blurred consent in social spaces: what counts as harmless, what gets dismissed as “just Richard,” and what women are expected to absorb for the sake of communal ease. Richard also functions as a temptation and a provocation; when Sam asks if Cora will sleep with him, it reveals Sam’s possessiveness and the way desire can turn into territorial thinking even inside an illicit relationship.

Celeste Hood

Celeste is a social architect, someone who stabilizes community through gatherings, shared routines, and curated friendliness. In The Ten Year Affair, her role in hosting dinners and later the farewell party positions her as a kind of town-stage manager, making her home a place where people perform versions of themselves.

Celeste’s importance lies in how she represents the collective: she doesn’t have to be malicious to be powerful, because in a small community, the person who hosts becomes the person who frames the story. Her spaces are where secrets have to coexist with smiles, where tension becomes ambiance.

Ryan

Ryan is the embodiment of workplace impermanence and the false promise of upward mobility. In The Ten Year Affair, his departure and the suggestion that Cora might replace him briefly offers her a narrative of renewal: a career turning point that could counterbalance the stagnation of marriage and suburbia.

The eventual decision to give the role to someone else—based on assumptions about Cora’s availability as a mother—reveals how institutions quietly punish caretaking, and how humiliation can harden into anger. Ryan is not just a boss; he’s the doorway that closes, reinforcing Cora’s sense that her life is being decided by other people’s expectations.

Lily

Lily appears primarily as the beneficiary of the workplace decision that sidelines Cora, and her function in The Ten Year Affair is to make the system visible. The point isn’t that Lily is villainous; it’s that she is legible to management in a way Cora isn’t.

Lily represents the kind of professional who fits the imagined template of “available,” reminding Cora that competence alone doesn’t secure power when social assumptions shape opportunity.

Anita

Anita, as the organizer of the book club, represents the social infrastructure of the town: the well-meaning attempt to create intimacy through structured gathering. In The Ten Year Affair, the book club becomes a stage for exclusion, rivalry, and moral projection, showing that community doesn’t automatically equal kindness.

Anita’s presence matters because she facilitates the environment where Jules and Cora’s tension finally erupts—proof that even benign social spaces can become arenas when people arrive carrying secrets.

Morgan

Morgan is not a person so much as a tactic, but that makes her revealing. In The Ten Year Affair, the invented coworker becomes the practical architecture of deceit, showing how affairs are sustained not only by passion but by administration—calendar gaps, plausible narratives, and the quiet confidence that no one will check.

Morgan’s usefulness also reflects the emotional blindness in Cora’s marriage: the lie works because Eliot isn’t looking too closely, and Cora knows it.

Themes

Infidelity and Moral Ambiguity

In The Ten Year Affair, infidelity operates not as a single transgression but as a sustained, complex mode of living. Cora’s affair with Sam stretches beyond moments of physical betrayal into an ongoing negotiation between passion and morality.

What begins as an impulsive kiss evolves into a shadow existence, parallel to her domestic life with Eliot. The narrative doesn’t sensationalize the affair; instead, it examines how sustained deception reshapes identity and ethics.

Cora’s guilt is diffuse—she is not tormented by moral failure as much as she is trapped by emotional inertia. The novel suggests that long-term infidelity becomes indistinguishable from routine, a kind of stability built on lies.

Sam’s complicity deepens this moral blur: both characters justify their actions through fatigue with marriage, loneliness, and the belief that their connection is “realer” than domestic life. Over time, the affair loses its erotic charge and becomes habitual, echoing the marriages it was meant to oppose.

Erin Somers portrays infidelity less as rebellion and more as resignation, a symptom of emotional stagnation. The novel forces readers to confront how morality frays under boredom and how love can exist alongside deceit.

By the end, the question is not whether Cora is “wrong” but whether she can live with the kind of person she has become—a woman whose duplicity defines her sense of being alive.

Domesticity and the Weight of Ordinary Life

Domesticity in The Ten Year Affair is both comforting and suffocating. Cora’s home, filled with broken appliances, recurring mold, and endless childcare, embodies the slow erosion of individuality within middle-class parenthood.

The novel captures how domestic spaces, once symbols of stability, become traps of routine. Eliot’s dependability contrasts with Cora’s restlessness; he represents the safe monotony that once felt desirable but now drains vitality.

Somers shows how domestic labor—cooking, cleaning, parenting—creates emotional invisibility, particularly for women. Cora’s affair is not simply about passion; it’s a rebellion against the repetition of diapers, PTA meetings, and dinner parties.

Yet, even in her transgression, she replicates the same patterns of care and maintenance. The affair itself becomes domestic in its own way—scheduled, familiar, predictable.

Through this cyclical structure, Somers critiques the myth of fulfillment through family life and the false dichotomy between stability and freedom. Cora’s yearning for intensity is inseparable from her exhaustion with the ordinary, revealing how both are parts of the same domestic machinery.

By the conclusion, domestic life reasserts itself—not as punishment but as inevitability. The novel implies that most lives oscillate between craving escape and clinging to order, with neither offering true satisfaction.

Female Identity and Self-Perception

Cora’s journey across the years of The Ten Year Affair reflects the fragmentation of modern female identity. As a wife, mother, employee, and lover, she inhabits roles that constantly demand performance.

Each sphere—home, work, motherhood, affair—requires a different version of her, none of which feel entirely authentic. Her affair with Sam provides a temporary illusion of selfhood, a space where she feels desired and visible.

Yet as the affair ages, it too becomes another stage for performance, one where she must maintain lies and appearances. Somers explores how women like Cora, educated and self-aware, can still be trapped in the contradictions of modern feminism: striving for autonomy while constrained by emotional labor and social expectation.

The novel is attentive to the quiet humiliations—being passed over for promotion, being criticized by her mother, being reduced to a “mom” at social gatherings—that collectively diminish her sense of worth. Cora’s infidelity becomes less about desire and more about reclaiming a feeling of significance, even if it’s self-destructive.

Her eventual acceptance of her flawed, aging self suggests not redemption but recognition—a weary acknowledgment that identity is fluid, contingent, and often incompatible with happiness.

Time, Aging, and the Illusion of Renewal

Time in The Ten Year Affair functions like a quiet antagonist. The novel unfolds over decades, showing how moments of passion and rebellion fade into habit and fatigue.

Aging transforms both desire and regret: what once felt daring becomes embarrassing, and what once felt unbearable becomes ordinary. Cora’s physical aging—her self-consciousness about her body, her declining energy, her nostalgia for youth—mirrors the emotional decay of her affair and marriage alike.

Somers uses time to dismantle the illusion of fresh starts. Each attempt at renewal—new house, new lover, new baby—ends in repetition.

The regrowing bathroom mushroom, the stalled biodiesel car, and the pandemic routines all symbolize cycles that never truly break. Even when Cora imagines alternate realities—having another baby, or choosing Sam openly—those fantasies dissolve into monotony.

The passage of years does not bring wisdom or closure but a clearer view of life’s circularity. By the final pages, time feels both oppressive and merciful: it dulls pain but also erases intensity.

Cora’s final moments of quiet domestic peace, watching a bird take flight, capture this paradox—freedom exists, but only as something fleeting, glimpsed before being absorbed again into the everyday.

The Collapse of Desire and Emotional Fatigue

Desire in The Ten Year Affair begins as a spark of vitality and ends as exhaustion. The early scenes between Cora and Sam are charged with humor and longing; they represent everything absent from her marriage—spontaneity, recognition, thrill.

But as the years pass, that same desire becomes burdensome. Their sex turns mechanical, their secrecy habitual, their connection tinged with resentment.

Somers shows how sustained transgression drains the very energy that once made it exciting. Cora’s longing shifts from physical passion to a yearning for meaning itself, for something that feels authentic in a life built on roles and pretenses.

Eliot’s depression, Jules’s bitterness, and Sam’s lack of direction all mirror this collective emotional fatigue—a generation disillusioned with both domestic comfort and romantic escape. The novel’s later chapters, set after the pandemic, make this fatigue nearly existential.

Cora and Sam’s renewed affair, complete with Paris escapades and sexual experimentation, feels desperate rather than liberating. In the end, the collapse of desire becomes the truest revelation: that intensity cannot sustain life, and that even passion, unchecked by reality, curdles into routine.

Somers captures this decline not with melodrama but with quiet inevitability, rendering a portrait of love’s slow erosion under the weight of time and familiarity.