The White Octopus Hotel Summary, Characters and Themes

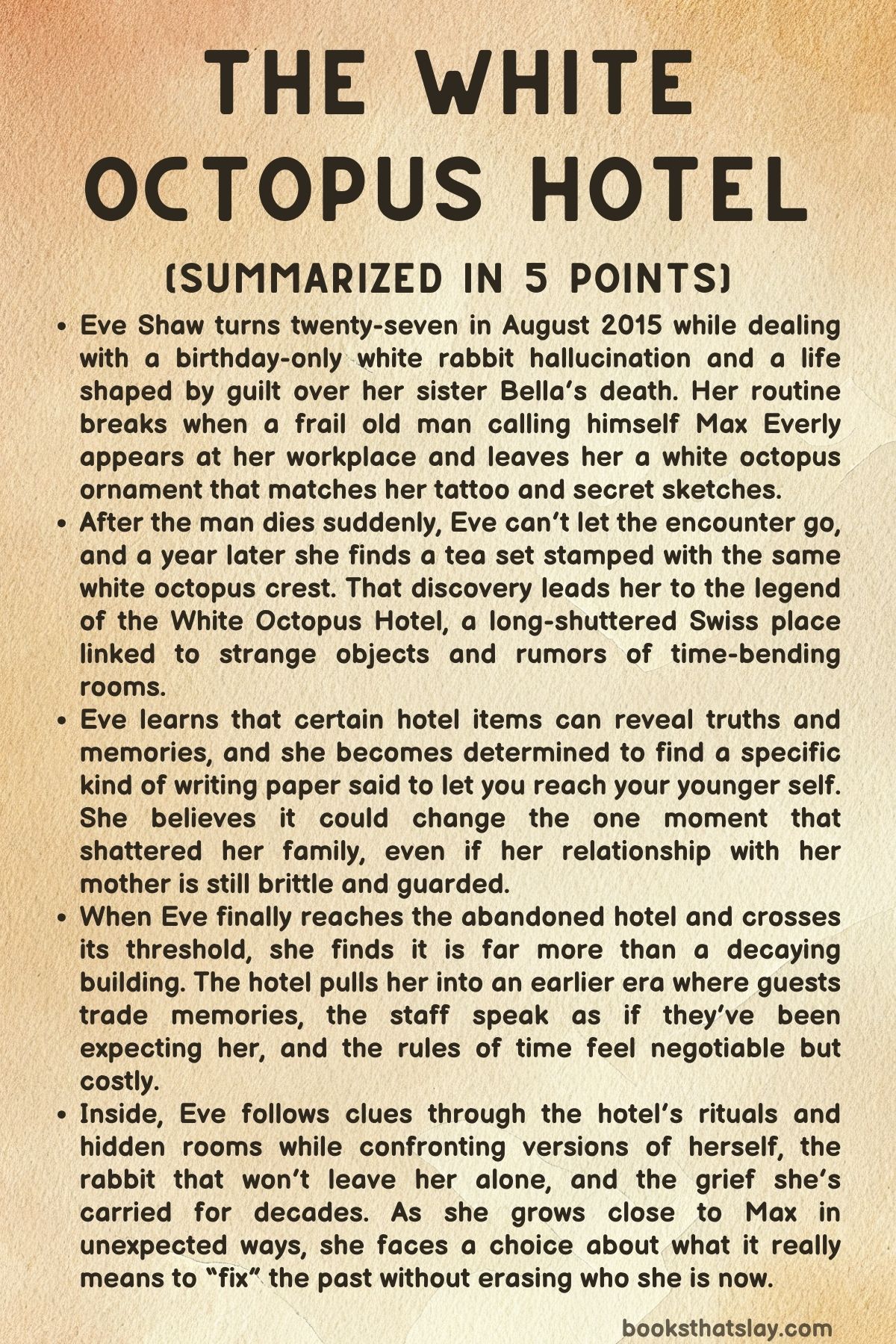

The White Octopus Hotel by Alexandra Bell is a time-bending story about guilt, second chances, and what it costs to rewrite the past. Eve Shaw turns twenty-seven under the weight of a memory she can’t shake: her little sister Bella died when they were children, and Eve has carried the blame ever since.

Every birthday, a white rabbit with a dark mark over one eye appears and follows her through the Underground, as if time itself won’t let her forget. When a frail stranger arrives at her auction house claiming to be the long-dead composer Max Everly, he leaves Eve a white octopus ornament that matches the designs she’s drawn for years.

Summary

On her twenty-seventh birthday in August 2015, Eve Shaw tries to get through the day by sticking to routine at Stanley’s auction house in London. She dresses in black, hides her tattoos, and keeps people at a distance.

The day is harder than usual because the birthday brings back the same unsettling vision she’s had for years: a white rabbit with a black patch over one eye, appearing like an omen and trailing her through the Underground. A brief, tense call with her mother leaves Eve raw, stirring up the old wound at the center of their family: Bella, Eve’s younger sister, died when they were little, and Eve has never stopped believing she caused it.

An elderly man arrives at Eve’s workplace insisting on seeing her. He gives the name “Max Everly,” which makes no sense, because Max Everly is Eve’s favourite composer and has been dead for decades.

When Eve meets him, the man is gentle and strangely familiar. He notices a small wartime good-luck charm on her desk and speaks in riddles about endings and beginnings.

Then he tells her she should stop only judging art and start making it. Before leaving, he places a small white octopus ornament on her desk, its tentacles elegant and one tip stained black, matching both Eve’s own secret sketches and the burning octopus tattoo under her clothes.

Eve accepts the gift mostly to calm him, but the encounter leaves her shaken. Moments later, outside the building, the man collapses on the steps and dies in front of her, thanking her as if she has already saved his life.

A year passes. Eve tries to escape her birthday by travelling to France, but the rabbit still appears.

She keeps the man’s fedora, marked with his initials, and the octopus ornament. In St Malo, she finds a damaged tea set stamped with a white octopus crest identical to her ornament, including the black-tipped tentacle.

Back in London, her colleague Kate mentions auction-house lore about a vanished place called The White Octopus Hotel, where objects were said to be uncanny and were scattered after the hotel closed under strange circumstances. Eve searches for proof and finds articles connecting the hotel to a Victorian painter, Nikolas Roth, who showed his work only there.

The reports describe a grand alpine hotel that shut its doors in 1935 during a final party, abandoned mid-celebration. When Eve sees a photograph of the building, she’s hit with a rush of recognition and homesickness that makes no rational sense.

Eve tracks down Victor Harris, a retired valuer fascinated by the hotel’s legend. He tells her believers collect objects from the place, each with its own rule: a telephone that can call the dead once, glasses that reveal what you need to see, and other items that seem to bend reality.

Victor also has a brass key marked “27,” said to belong to a room that can move someone through time. He’s spent years hunting for the hotel’s rare writing paper, rumoured to let you send a message to your younger self.

Eve’s hope sharpens into obsession: if she could reach the past, maybe she could prevent Bella’s death.

Testing the octopus tea set at home, Eve drinks and is thrown into a vivid vision of a nurse in another era, caring for wounded men while old music plays. The shock confirms the objects are real, not just stories.

Eve confronts her parents for answers. Her father denies anything unusual about a Swiss trip long ago.

Her mother reacts tensely but admits they visited the hotel when it was already abandoned, and she produces a photo of its ruined lobby. In the corner is a blurred, small child who is unmistakably Eve.

Before Eve leaves, her mother mentions finding a key to a room number that didn’t seem to exist, adding another puzzle piece to Eve’s growing certainty that the hotel is tied to her life.

Eve takes leave from work and travels to Switzerland, following the faint trail of the hotel’s location near a mountain lake. The villagers speak of fog and oddness surrounding the building.

A local woman ferries Eve across the freezing water. Eve loses her small good-luck charm into the lake, then enters the decaying hotel alone.

Inside, the ruin matches her mother’s photo exactly: dust, damaged marble, a dead fountain carved into an octopus. When she rings the reception bell, sensations flood her—music, laughter, peppermint, a warmth that doesn’t belong in an abandoned shell.

Searching the upper floors, she can’t find Room 27. In a dark bar, the rabbit appears again, tugging Eve into memories of Bella, of an apple, of a gate left open, of a life split in two.

In the library she finds a photo of the lobby in its prime, and in it stands a woman who looks like Eve.

At last she finds a door marked as Room 27 on one side and Room 28 on the other. Using the key, she triggers a blinding flash and wakes in a restored, bustling hotel.

It is 1935, the night of the hotel’s fortieth anniversary celebration. A bellhop named Alfie calmly explains that some guests arrive “from the future” and that the hotel trades in memories instead of money: when Eve leaves, she must surrender her recollection of her stay.

Eve is given a gown identical to one in the photograph she found, as if the hotel has been expecting her.

Eve meets members of the Roth family and learns the hotel hides rules inside its luxuries. There is a scavenger hunt tied to clocks and octopus symbols, with a final prize: the last piece of special writing paper, locked away.

Eve believes it can help her save Bella. The hotel also confronts her with the people she once was: she sees her younger self visiting the hotel with her pregnant mother years earlier, and she watches that child’s tantrums with a harshness that turns into shame.

In the lobby, the composer Max Everly appears, younger and alive, performing small tricks for the child Eve. Time itself stutters when a lobby clock is wound, rewinding the last five minutes as if the building is casually toying with cause and effect.

As Eve searches for answers, she is pulled into the hotel’s stranger layers: corridors stained with ink, paintings that act like doors, and keys marked with numbers that correspond to different crossings. She is flung into Max’s past during the First World War, where he is haunted, wounded, and saved by a nurse who is Eve herself.

Their bond forms across impossible timelines: Eve steadies Max when he wants to die, and Max becomes devoted to her in return. Back in 1935, Eve and Max reunite with the weight of those memories between them, and their connection turns physical, tender, and complicated by everything Eve is trying to change.

The scavenger hunt tightens around Eve. Objects appear and vanish: a music box with an octopus perched on it, clocks hidden inside toys and globes, mirrors that show other lives, and moments where the hotel’s polished mask slips into ruin.

Eve learns the hotel is not only a place but a mechanism, and the price of using it may be measured in lives, not luck. When she finally wins and the writing paper is offered, the truth lands with force: changing what happened to Bella demands a chain of deaths and rewinds that would erase far more than one tragedy.

Eve cannot accept saving her sister by destroying Max and others. The Roth siblings reveal an even deeper twist: they are connected to Eve and Max in ways that collapse past and future into one family line, and the hotel itself is tied to what Eve and Max will create together.

Eve faces a final choice: return to her own time with her guilt intact, or commit to a life with Max that will still contain hardship, loss, and the cost of the hotel’s rules. She chooses to rewind the hotel’s great clock and step into a shared future with him, not as an escape from pain, but as an acceptance that love and grief can exist in the same life.

In the closing view of their later years, the hotel’s magic remains a quiet companion as they age. Eve dies with Max holding her hand, and when he is left alone, he prepares to use the hotel’s doorways once more, holding to the idea that an ending can also be a beginning.

Characters

Eve Shaw

Eve Shaw stands at the heart of The White Octopus Hotel, a woman consumed by guilt, haunted by loss, and driven by an unrelenting need to make sense of the past. Her journey begins as that of a withdrawn, isolated woman whose life has been shaped by the tragic death of her younger sister, Bella.

The recurring hallucinations of the white rabbit — a symbol directly connected to Bella’s death — act as a physical manifestation of Eve’s internal torment. Her fascination with forgotten objects, art, and the supernatural speaks to a deeper yearning to recover fragments of what was lost.

As she becomes entangled with the mysterious Max Everly and the enigma of the hotel, Eve’s arc transforms from one of grief to self-discovery. Her descent into the hotel’s surreal world blurs the lines between memory, dream, and reincarnation, forcing her to confront not only her guilt but also the cyclical nature of life and love.

Through her relationship with Max, she discovers that her existence is not linear — she is both the haunted and the haunter, both the mother and the daughter. Eve’s eventual acceptance of time’s fluidity and her willingness to embrace both love and loss form the emotional core of her redemption.

Max Everly

Max Everly embodies the intersection between art, time, and love. Introduced first as an enigmatic old man who dies on Eve’s birthday, Max later reemerges as a young composer from 1918, making his presence both spectral and eternal.

His character symbolizes the persistence of creative passion beyond death and the way love echoes through generations. As a war survivor, Max carries the weight of trauma, guilt, and artistic obsession.

His connection to Eve is both mystical and tragic — they are lovers divided by time, drawn together across lives, and bound by the supernatural power of the White Octopus Hotel. Through Max, the novel explores the redemptive potential of art: music becomes a bridge between timelines, emotions, and souls.

His love for Eve, profound yet painful, leads to acts of both salvation and sacrifice. Ultimately, Max’s faith in Eve’s courage and his willingness to let her choose her path — even when it means separation — elevate him from a romantic figure into a timeless embodiment of devotion and creative transcendence.

Bella Shaw

Though Bella’s physical presence in the story is brief, her death defines the emotional landscape of The White Octopus Hotel. She exists as both memory and ghost, an innocent victim whose loss fractures Eve’s family and psyche.

The recurring imagery of the white rabbit — Bella’s childhood toy and symbol — continually reminds Eve of her perceived responsibility for the accident. Yet as the story unfolds and the boundaries between past and present blur, Bella’s presence becomes transformative rather than purely tragic.

She represents innocence, forgiveness, and the possibility of renewal. Through magical realism, Bella’s spirit evolves from a figure of guilt into one of reconciliation, guiding Eve toward self-forgiveness.

Her existence within the hotel’s many mirrors and echoes serves as a gentle reminder that love persists, even through grief and distortion.

Jane Shaw

Jane, Eve’s mother, is a woman defined by repression, bitterness, and unresolved grief. Her relationship with Eve is cold and fractured, marked by the infamous question that haunts them both: “Did you close the gate?” Jane’s inability to forgive — either her daughter or herself — mirrors Eve’s own self-punishment.

The decades of silence between them are emblematic of generational trauma, where sorrow and blame are inherited rather than healed. Yet beneath Jane’s hardness lies deep sorrow and regret.

Her eventual confrontation with Eve reveals not cruelty, but a mother’s inability to face the pain of losing a child. In her photo of the ruined hotel and her mention of Room Seventeen, Jane becomes an inadvertent keeper of memory, linking Eve’s reality with the supernatural.

Her arc, though subtle, provides one of the story’s most human dimensions — the frailty of a parent unable to bear the reflection of their own grief.

Nikolas Roth

Nikolas Roth is the mysterious founder of the White Octopus Hotel and the artistic mind behind its haunting legacy. A visionary painter, Roth represents the archetype of the creator who fuses art and the supernatural, blurring reality and imagination.

His hotel is less a physical space than a living organism — a gallery of souls, dreams, and regrets suspended in time. Though he rarely appears directly, his influence is omnipresent.

Roth’s cryptic scavenger hunt, his fascination with clocks, and his manipulation of time suggest a man obsessed with capturing eternity through art. Later revelations that Eve and Max may embody Roth’s identity in another form deepen the novel’s meditation on creation and reincarnation.

Roth’s legacy is thus both a curse and a gift — the immortalization of love and memory within the decaying walls of art.

Anna Roth

Anna Roth, Nikolas’s daughter, represents the blurred boundary between guardian and ghost, human and myth. Her dual identity — first as the enigmatic hotel custodian, then as Eve and Max’s future daughter — redefines the reader’s understanding of lineage and destiny.

Anna’s role as both protector and manipulator of time gives her a complex moral dimension. She serves the hotel’s cyclical order, ensuring that its balance between creation and destruction is preserved.

Her emotional fragility, expressed through her tears and her fierce love for the hotel, hints at the burden of knowledge she carries — understanding that her own existence is paradoxical. Through Anna, the novel confronts the consequences of defying time and the pain of eternal recurrence.

Tristan Roth

Tristan, the hotel’s librarian and clockkeeper, embodies wisdom, melancholy, and quiet devotion to order. His stewardship of the clocks — instruments that literally bend time — makes him a custodian of history and memory.

Tristan’s demeanor is calm and philosophical, contrasting the chaos that swirls around the hotel’s guests. He becomes a guide for Eve, showing her that time is both mechanical and emotional.

His connection to Anna and the other Roths reinforces the idea that the family serves as the hotel’s conscience, maintaining its rhythm even as it decays. Tristan’s presence also symbolizes the intersection of logic and wonder — the craftsman who understands that every mechanism, whether of gears or hearts, requires both precision and belief.

Mrs. Roth

Mrs. Roth functions as the hotel’s matriarchal presence — a figure of fading grandeur, memory, and compassion. Her conversations with Eve reveal an awareness that transcends ordinary time; she speaks in riddles that reflect both wisdom and resignation.

Through her, the novel meditates on the burden of long life and the loneliness of watching time consume beauty. Mrs. Roth’s reflections on her lost daughter and her advice to Eve about the dangers of rewriting the past mark her as both mentor and warning.

She embodies the cost of living too long within the confines of memory, suggesting that love without release can turn to sorrow.

Alfie

Alfie, the young bellhop, introduces a sense of warmth and humanity amidst the novel’s surrealism. Cheerful and kind, he acts as the first bridge between Eve’s modern consciousness and the hotel’s enchanted world.

As Nikolas Roth’s grandson, Alfie is linked to the hotel’s legacy, yet his youthful innocence allows him to navigate its magic with acceptance rather than fear. He welcomes Eve as though her arrival were expected, establishing the tone of the hotel as a place where time is not linear but cyclical.

Through Alfie, the story briefly recalls the wonder of childhood — an echo of the innocence Eve and Bella once shared.

Victor Harris

Victor Harris serves as a narrative catalyst, introducing Eve to the mythos of the White Octopus Hotel and its magical objects. As a retired valuer and storyteller, he represents the human fascination with mystery and the desire to find meaning in forgotten relics.

His pragmatic skepticism is balanced by a quiet belief in magic, making him a bridge between the rational and the supernatural. Victor’s possession of the key to Room 27 and his tales of miraculous objects propel Eve’s transformation from passive observer to active seeker.

His role underscores one of the novel’s core themes: that even ordinary people are drawn to the extraordinary when it offers the promise of redemption.

Themes

Guilt, grief, and the need for absolution

Eve’s adult life in The White Octopus Hotel is structured around a loss she never metabolized: Bella’s death on Eve’s fourth birthday and the accusation that followed, “Did you close the gate?” The recurring white rabbit is not just a spooky motif; it behaves like a fixed point in Eve’s calendar, showing up on birthdays as if the mind has scheduled an annual audit of blame. Eve’s habits—dressing in black, hiding tattoos, keeping her work solitary and controlled—read as a long attempt to live in a world where nothing unexpected can happen again.

Even the setting of an auction house, with its emphasis on cataloguing, condition, provenance, and price, echoes her psychological effort to turn chaotic pain into something measurable. But grief does not cooperate with measurement.

It breaks into the everyday through hallucination, body sensation (the burning tattoo), and sudden recognition of places she “couldn’t” have been. The story keeps returning to moments where Eve wants a single clean verdict: guilty or innocent, fixable or final.

That desire explains why she latches onto the hotel’s rumored writing paper and the idea of sending a message to her younger self. If she can correct one action—close the gate, stop the chain reaction—then her mother would not have shattered, Bella would live, and Eve’s adulthood would not feel like a sentence she is serving.

Yet the narrative steadily complicates the fantasy of a simple undoing. The hotel’s rules, the repeated insistence that tragedy is not always someone’s doing, and Eve’s encounter with her younger self all challenge the cruelty of retroactive blame.

The child version of Eve is small, impulsive, hungry for cake, not a villain with adult foresight. By forcing adult Eve to witness that reality, the story reframes guilt as something that can attach itself to an innocent mind and then harden over decades into identity.

The movement of the plot is less about proving Eve “not responsible” and more about loosening the grip of punishment that has replaced mourning, so that love, creativity, and honest connection can exist again without requiring a miracle to justify them.

Memory as currency and the fragile construction of identity

The hotel’s most unsettling bargain is that it “deals not in money but in memories,” demanding that guests surrender recollection when they leave. That rule turns a familiar idea—memory shapes who we are—into a literal transaction with consequences.

Eve’s obsession with remembering is already intense before she reaches the Swiss Alps: she replays the birthday crash, her mother’s shaking hands, the missing comfort, the single question that became a lifelong wound. In that context, a place that threatens to erase memory is not merely magical; it is an attack on the one thing Eve believes she still possesses: the right to hold the past and use it as evidence.

At the same time, the story shows how memory can be a trap. Eve’s recollections are selective and contaminated by guilt, to the point where she experiences the rabbit as an external pursuer rather than an internal signal.

The tea set’s visions push this further by giving her other lives, other times, and other bodies—suggesting that memory is not always personal property and that identity may be more porous than Eve wants to believe. This is especially sharp when she sees the woman identical to herself in an old photograph and feels a homesickness that has no rational source.

The plot treats that recognition as real, not a metaphor, and asks what it means if your sense of self includes experiences you never “lived” in your timeline. The hotel’s clocks, rewinds, and mirrored scenes underline that the self is assembled from repeated moments, not a stable core.

Even the scavenger hunt becomes a test of what Eve can record and keep: some written evidence vanishes, some stays, and the difference matters. When the story reveals that Eve becomes “Nikolas Roth” and helps create the very institution she is trying to exploit, it turns identity into a loop: Eve’s future self authors the conditions that shape her past self’s choices.

In that light, memory is not just content in the mind; it is infrastructure. Taking away memories is like removing the beams from a house and expecting the rooms to remain.

The theme lands hardest in Eve’s fear that leaving the hotel could erase the very experiences that finally make her feel understood and alive. The question becomes painful and practical: if healing happens but you cannot remember it, did it happen in any meaningful sense?

The narrative suggests that remembering is part of healing, but it also warns that clinging to memory as proof can freeze a person in the worst hour of their life.

Time, choice, and the ethics of rewriting what happened

Time travel in The White Octopus Hotel is not presented as a fun escape hatch; it functions as a moral pressure cooker. Eve arrives with a clear agenda—find the writing paper, prevent Bella’s death, repair her mother—and the hotel seems built to tempt that agenda with tools that look like solutions.

But every mechanism that touches time carries a cost: five-minute rewinds, forty-year jumps, rooms that only exist for certain people, and, most brutally, the claim that bringing Bella back would require eight deaths. That number forces the reader to confront what “saving” means when the price is paid in other lives.

Eve’s initial plan is shaped by a child’s logic trapped in an adult body: if one mistake created this pain, one correction can erase it. The hotel’s systems argue the opposite.

They imply that changing the past is not a neat edit; it is a reconstruction that demands sacrifice and produces new losses. The ethical tension is intensified by Eve’s growing love for Max.

If Bella is restored at the cost of Max and others, then Eve becomes the author of a different tragedy. The story refuses to let her keep moral cleanliness by treating the alternative deaths as abstract.

Max is present, vulnerable, and increasingly irreplaceable, so the choice becomes personal rather than ideological. Even the revelation that Eve and Max’s children exist as Anna, Harry, and Tristan sharpens the dilemma: choosing to rewind or not is also choosing whether those children will exist.

Time travel turns into a question about responsibility across generations, not just across days. The narrative also complicates “choice” by showing how often Eve is guided, tricked, or cornered.

Anna locks her in Room 17; the hotel produces doors and signs; objects appear and vanish; the environment reacts to her fear. Agency is real, but it operates inside a maze designed by people who already know parts of her story.

That is why the final decision—to wind the clock, to accept a hard life with Max rather than a fantasy of perfect repair—feels like an ethical maturation. Eve stops chasing a purified timeline and chooses a life that includes grief without being ruled by it.

The theme does not claim that accepting loss is easy or virtuous in a simple way; it shows that rewriting the past can become another form of denial, one that spreads harm outward. Time travel becomes a mirror for any human wish to reverse a defining event, and the story’s answer is not “never want that,” but “face what your wanting would demand from others.”

Art, music, and creation versus appraisal

Eve begins as someone trained to assign value to paintings, to translate human feeling into market categories. Her world at Stanley’s auction house rewards distance: the ability to stay cool, to see an object’s worth without being pulled into its meaning.

Max Everly’s intrusion disrupts that system immediately when he tells her to stop valuing paintings and start creating masterpieces. The line is provocative because it attacks Eve’s survival strategy.

Appraisal allows her to keep emotion at arm’s length; creation would require exposure. The octopus ornament, matching her secret sketches and tattoo, acts like evidence that her private imagination is not trivial, not “just doodles,” but part of a deeper identity she has refused to honor.

The hotel expands this conflict by surrounding Eve with art that is not neutral décor but living machinery: paintings that release apples, walls that open into ink corridors, portraits that mutate, and spaces that appear only when someone is meant to see them. In this environment, art is not a commodity; it is an active force that can trap, reveal, and transform.

Music functions similarly. Max’s compositions are not background entertainment; they soothe soldiers, alter perception in the baths, and become artifacts that outlast the people who made them.

The mirrored piano music box engraved with a declaration of love embodies the theme in a concentrated form: the object is beautiful, intimate, and impossible to price honestly because its value is relational. Eve’s job taught her to ask “what is it worth?” but the story keeps pushing her toward “what is it for?”—comfort, survival, connection, witness.

This matters for Eve’s healing because grief has turned her into an evaluator of herself, grading her past and assigning herself a permanent negative verdict. Creative work offers a different language: you cannot create from a place of pure self-contempt without eventually collapsing.

The later reveal that Eve becomes the hotel’s founder figure and that Max’s music becomes the music boxes reframes their talents as a way of building a refuge for others, especially the damaged and displaced. Art becomes care given a physical form.

Even the auction lore about magical objects being scattered after the hotel’s closure echoes a cultural truth: when art is treated only as property, its deeper purpose fractures. The theme argues that creating and sharing meaning is not a luxury; it is one of the ways people endure what cannot be fixed.

Family rupture, blame, and the long afterlife of one accusation

The relationship between Eve and her mother is shaped less by what they say than by what they cannot say. Their calls are strained, brief, loaded with decades of avoidance.

When Eve finally returns to her childhood home, the gate is more than a setting detail; it is a symbol of the boundary where childhood ended and a family’s internal structure failed. The crash on Eve’s fourth birthday is portrayed through a child’s sensory experience—cake, banners, a tantrum—then immediately through adult panic, sirens, waiting, and a phone call that transforms the house into a place of dread.

The most damaging moment is not simply Bella’s death but the absence of repair afterward. Eve runs to her mother for comfort and receives shaking hands and a hissed question.

That reversal—child reaching out, parent turning the child into a suspect—creates a blueprint for Eve’s adult loneliness. It also traps the mother in her own injury.

The story does not excuse her cruelty, but it makes clear that grief can deform a person’s ability to care, especially when they cannot tolerate randomness and need a target for rage. The mother’s later obsession with abandoned buildings and her photograph of the ruined hotel lobby suggest a mind drawn to places that mirror her interior: preserved damage, frozen loss, the comfort of decay because it matches what she feels.

When she tells Eve they never stayed at the hotel “in a manner of speaking,” the phrasing captures how trauma distorts truth. The mother is simultaneously hiding and confessing, trying to control the narrative while needing someone to finally hear it.

Eve, meanwhile, seeks supernatural technology as a substitute for conversation. It is easier to hunt writing paper than to sit across from her mother and risk being blamed again.

The hotel forces that confrontation indirectly by placing Eve beside her younger self and her pregnant, exhausted mother at tea. Seeing her mother snap at the child version of herself adds nuance to Eve’s anger: the mother was already strained, already limited, already human, not a pure villain.

This does not erase harm; it contextualizes it. The theme ultimately examines how families can become stuck in a single moment, repeating it in different forms for decades.

The rabbit that returns every birthday functions like a family ritual of pain that no one agreed to but everyone participates in. Healing, in this frame, is not only forgiving the self; it is also recognizing that blame was a misguided attempt to impose order on chaos, and that breaking the pattern requires a new story—one that makes room for love that was never expressed, grief that was never held, and responsibility that does not become lifelong punishment.

Love, intimacy, and fear of attachment when the future is unstable

Eve’s connection with Max is charged from the start because it violates ordinary logic: he arrives under an impossible name, recognizes her, gives her an object that mirrors her own private imagery, and dies in her presence. Their bond is therefore haunted before it becomes romantic.

When Eve later meets Max in the hotel’s past, the relationship grows in conditions that intensify everything—war aftermath, temporary sanctuary, and the knowledge that time can separate them at any moment. Eve repeatedly tells herself it is friendship, partly because admitting love would mean risking another loss she cannot survive.

Her reluctance to say “I love you” even after intimacy is not coyness; it is self-protection shaped by Bella’s death and her mother’s emotional withdrawal. If love equals vulnerability, and vulnerability once led to catastrophe, then withholding becomes a way to stay safe.

Max, by contrast, expresses devotion through music and through a readiness to orient his life around Eve, even when he suspects it will hurt. The mirrored piano music box that appears and then vanishes captures the instability of their intimacy: a gift that proves love exists, then disappears as if the universe refuses to let it be kept.

The hotel itself pressures the theme by making memory the price of departure. Love usually relies on shared memory—private jokes, small rituals, remembered tenderness.

If those can be stripped away, love becomes fragile, almost theoretical. The story tests whether affection can survive not only distance but erasure and paradox.

It also complicates love with the revelation of children and the life Eve and Max build across decades. Love is not just a feeling; it becomes a commitment that generates consequences, including family, war, aging, and death.

Eve’s final refusal to trade eight lives for Bella, and her choice to wind the clock toward a difficult future with Max, reframes love as an ethical stance. She chooses a relationship that will include sorrow rather than a fantasy where no one dies.

That choice does not romanticize suffering; it asserts that love is not validated by perfection but by presence, honesty, and endurance. The last movement, with Max preparing to use the key to find Eve again, turns attachment into a kind of faith: not a denial of death, but a refusal to let death be the only truth.

Love becomes a counterweight to guilt, offering Eve a way to live forward without needing the past to be rewritten into a painless version.

Endings, beginnings, and the acceptance of a life that cannot be made spotless

From the first encounter with “Max Everly,” the story is marked by statements about endings being beginnings, but it earns that idea by showing how brutal endings can be. Bella’s death ends a childhood; Max’s collapse on the auction house steps ends the possibility of simple explanations; the hotel’s closure mid-party ends an era with eerie suddenness.

The abandoned building, preserved as if time stopped, externalizes the temptation to freeze life at one moment and never move again. Eve’s obsession with going back is an attempt to reject endings entirely, to treat death and regret as administrative errors that can be corrected with the right key.

The hotel repeatedly undermines that fantasy through its rules and through the emotional reality Eve encounters. A clock can rewind five minutes, but it cannot erase what those five minutes meant.

A door can open into 1935, but it cannot guarantee that returning will make anyone whole. Even the magical objects, for all their wonder, do not produce a clean rescue; they produce insight, confrontation, and cost.

The revelation that Eve becomes part of the hotel’s origin story is crucial here. It suggests that beginnings are not pure starting lines; they are built out of earlier endings, griefs, and choices.

The hotel itself, born from Eve and Max’s lives, is a monument to the idea that people try to make meaning out of what they cannot prevent. When Eve chooses not to resurrect Bella at the cost demanded, she is not “giving up” on Bella; she is refusing a false beginning purchased through other endings.

The narrative then offers a different kind of beginning: a chosen life with Max that contains hardship, aging, and eventually death, but also contains music, children, and moments of joy that are not canceled by sorrow. The final image of Max seeking Eve again affirms that acceptance is not the same as resignation.

The ending is still painful, but it is not portrayed as meaningless. The story’s emotional thesis becomes clear: the desire to undo loss is human, but living requires a willingness to let some events remain final while still allowing life to grow around them.

In that sense, “ending as beginning” is not a clever slogan; it is the only way the characters can honor what they loved without being destroyed by what they lost.