The Zorg by Siddharth Kara Summary and Analysis

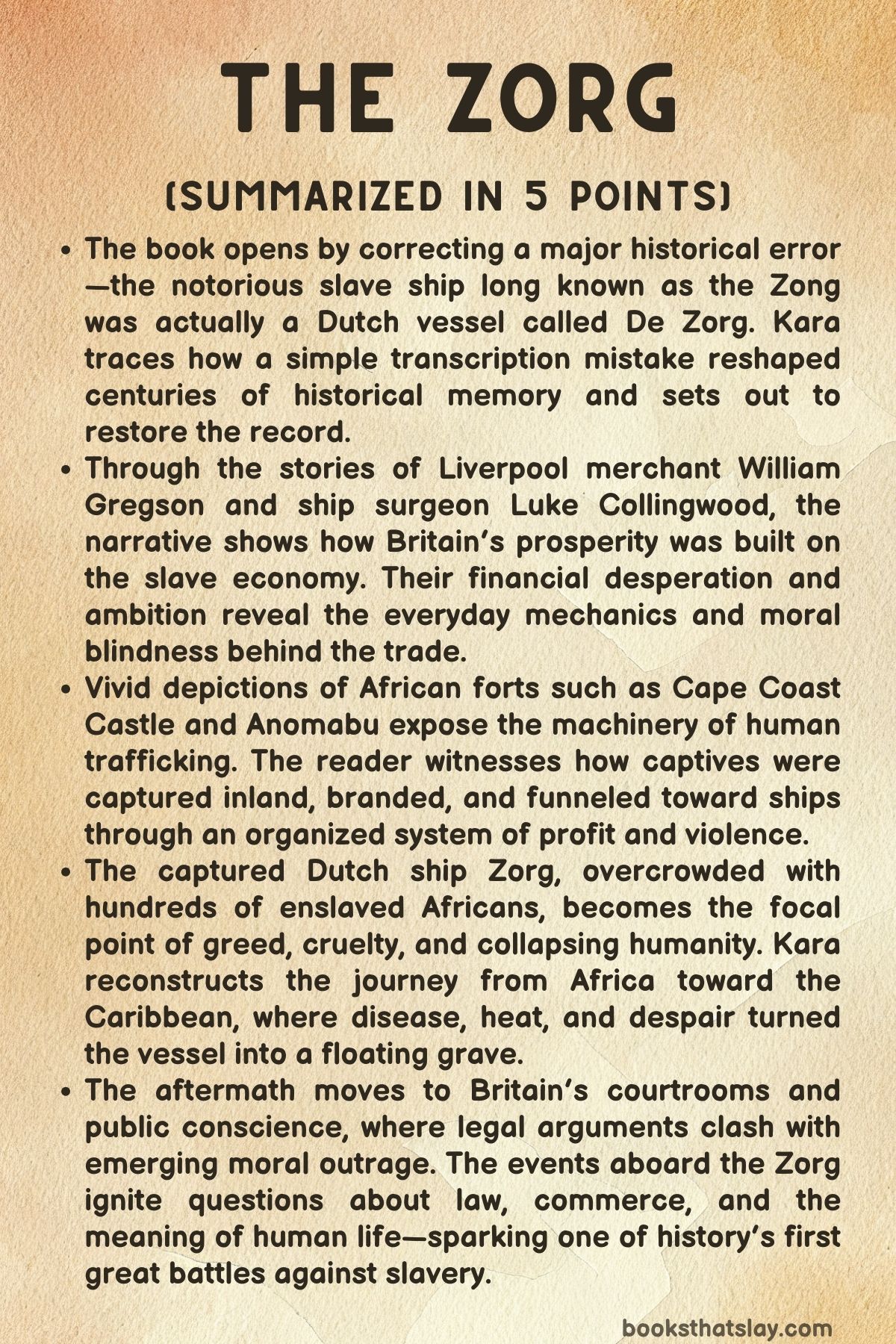

The Zorg by Siddharth Kara is a work of narrative history that reconstructs the story behind one of the most notorious episodes of the transatlantic slave trade. It begins by challenging a detail many people think they know: the ship remembered as the “Zong” was originally a Dutch vessel named De Zorg, its name altered by a small reading mistake that hardened into accepted history.

From there, the book follows the people, profits, and institutions that made such voyages possible—merchants in Liverpool, forts on the West African coast, and courts in London—showing how a massacre at sea could be argued as a routine insurance dispute, and how exposing that logic helped energize British abolitionism.

Summary

The story opens by correcting the record: the slave ship widely known as the Zong began life as a Dutch vessel called De Zorg, meaning “Care.” A misread letter turned “Zorg” into “Zong,” and that error repeated until it became the name attached to the ship’s crimes. This correction is not treated as a small technicality.

It becomes a reminder of how easily the identities of ships, and the lives trapped inside them, can be blurred by careless retelling. With the name clarified, the narrative steps back to explain the machinery that produced slave voyages: European maritime expansion, sugar plantations and their labor demands, and the steady rise of a trading system that exchanged manufactured goods for human beings and then sold plantation products back into European markets.

By the eighteenth century, Britain’s economy—especially its Caribbean wealth—depended on this system, and ports like Liverpool became specialists in human trafficking.

Against this backdrop, the book follows Luke Collingwood, a man trained as a surgeon who makes his living aboard slave ships. He is portrayed not as a monster from another world, but as an ordinary participant shaped by grief, ambition, and financial pressure.

After the death of his infant son and with his prospects limited, he accepts another voyage. His work is both medical and managerial: he must keep sailors healthy enough to operate the ship and keep enslaved Africans alive long enough to be sold.

The cruel arithmetic is constant. His pay and status rise when “cargo” survives, even though the methods used to force survival—branding, confinement, punishment, starvation-level provisioning—are themselves forms of violence.

Collingwood’s employer is William Gregson, a powerful Liverpool merchant who embodies the city’s transformation into a major slave-trading hub. Liverpool’s docks, shipping expertise, and finance networks make it efficient at fitting out voyages and turning people into profit.

But war shakes that structure. The American Revolutionary War disrupts shipping routes, threatens vessels at sea, and weakens commercial confidence.

Gregson suffers losses and sees previous ventures fail. In response, he finances another voyage as a high-stakes attempt to recover his fortune.

The ship is stocked with trade goods used to buy captives—textiles, weapons, liquor, beads, and cowrie shells—alongside the supplies and restraints needed to transport hundreds of chained people across the Atlantic.

The narrative shifts to the West African coast and to the forts that function as the trade’s coastal engines. Places like Cape Coast Castle are presented as fortified warehouses of captivity: administrative offices and barracks above, and dungeons below where men, women, and children are held in heat, darkness, and filth until they are sold.

Enslaved labor sustains the fortress itself, from maintenance to food production. The human pipeline feeding these forts is traced inland, where captives are taken through raids, wars, and organized slaving expeditions.

Prisoners are forced into chained marching columns and driven for hundreds of miles to markets, then sold onward through layers of traders until they reach the coast. At each handoff the price increases, and at each stage the captive’s identity is reduced further, first to a commodity and then to a unit in a ledger.

Alongside these scenes, the book introduces Granville Sharp, a London clerk whose earlier efforts to help an abused Black man pushed him into antislavery legal work. Sharp becomes important later not because he controls events at sea, but because he refuses to accept the legal language used to excuse what happens there.

Another key figure is Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved African who gains his freedom and becomes an organized voice against the trade. Their roles show how the battle over slavery is fought not only on ships and plantations, but also through letters, testimony, and public argument.

The central ship enters the story through wartime seizure. De Zorg, sailing as a Dutch slaver, is captured by a British privateer after Britain declares war on the Dutch Republic.

Already carrying enslaved Africans, it is taken as prize property. Captives from other seized ships are added, increasing the number trapped below deck.

This creates a floating crisis before the voyage truly begins: the ship is crowded, the crew is insufficient, sickness spreads, and the captives’ survival becomes less likely by the day. In the trading zone near the forts, Gregson’s interests converge with this captured vessel, and control shifts into British hands.

Collingwood is placed in command, and the ship is prepared for departure under conditions that are dangerous even by the standards of the slave trade.

As the ship leaves Africa in 1781, it carries hundreds of enslaved people in a space that cannot humanely hold them. The crew is small, the air below deck is foul, sanitation is minimal, and disease and dehydration worsen as the crossing drags on.

Navigation problems and delays intensify fear about water supplies and about profits. The book explains the legal incentive that makes the coming decision possible: insurers might reimburse owners for enslaved people lost as “cargo” in an emergency jettison, but not for deaths attributed to disease or neglect.

That distinction encourages a form of accounting logic in which murder can be reframed as maritime necessity.

Over multiple days, the crew throws large numbers of enslaved Africans overboard alive, selecting people described as sick, weak, or burdensome. Some captives jump into the sea rather than remain on the ship.

The killings are later defended as essential to preserve water for those remaining, yet evidence suggests the situation is not as the owners claim. When the ship reaches Jamaica, the story does not end with arrival.

It shifts into the courtroom, where the deaths are argued in the cold terms of insurance loss.

In London, the case Gregson v. Gilbert becomes a public flashpoint.

An observer notes with horror that the drowned Africans are treated as property rather than as victims of homicide. An anonymous letter to a newspaper describes the trial and forces readers to confront what the legal process is refusing to name.

Equiano brings the report to Sharp, and Sharp pushes for accountability, pressing the issue as murder rather than mere commercial dispute. In court, testimony and questioning expose contradictions, including evidence that rainwater had been collected before additional killings occurred.

The presiding judge signals that the matter demands closer scrutiny, and a retrial is ordered. Even so, criminal punishment never arrives.

What does emerge is lasting public outrage. The story of De Zorg—misremembered as the Zong—becomes a catalyst for abolitionist organizing, shaping how Britain’s slave trade is debated and, eventually, challenged as a national crime rather than a private business.

Key People

Luke Collingwood

Luke Collingwood stands at the moral and psychological center of The Zorg, embodying the contradiction of a man torn between conscience and complicity. Once a ship’s surgeon driven by financial desperation and personal tragedy—the death of his infant son—Collingwood returns to the slave trade despite his evident distaste for its horrors.

His character captures the uneasy intersection of science, commerce, and morality in the eighteenth century. As a doctor, he is charged with preserving life, yet his income depends on treating human beings as cargo.

The novel traces his gradual descent from reluctant participant to active perpetrator, culminating in his decision to jettison over one hundred enslaved Africans. Collingwood’s moral corrosion reflects both the corrupting power of economic necessity and the blindness fostered by an inhuman system.

His deteriorating health mirrors the decaying moral fabric of the world he inhabits, and his death shortly after reaching Jamaica symbolizes the ultimate collapse of a man who could neither atone nor escape his guilt.

William Gregson

William Gregson represents the institutional and civic embodiment of Britain’s slave economy. As a wealthy Liverpool merchant and former mayor, he epitomizes the respectability of cruelty disguised as enterprise.

Gregson’s rise from humble rope-maker to one of Liverpool’s dominant slave traders reveals the city’s transformation through slavery’s profits. His investments, risks, and failures mirror the economic pulse of the trade itself—driven by ambition, greed, and denial.

Gregson’s involvement in the insurance case following the Zorg massacre exposes how deeply commerce had divorced morality from legality. To him, the drowned Africans are not victims but lost assets, and his courtroom defense underscores the dehumanizing logic that allowed atrocity to masquerade as business.

Gregson’s character functions not merely as an individual but as an indictment of an entire society that normalized profit from human suffering.

Richard Hanley

Captain Richard Hanley, Gregson’s nephew, is a figure of maritime discipline and inherited entitlement. His authority aboard The William and later his dealings at Cape Coast Castle portray him as a professional steeped in the codes of command and obedience that defined the slave trade’s operations.

Hanley’s composure and pragmatism mask a deep moral emptiness: he enforces brutality as routine, maintaining order through fear and efficiency. Though less overtly cruel than some, his indifference is equally chilling.

Hanley’s interactions with Collingwood reveal a hierarchy where economic survival overrides empathy. His role as a link between Gregson’s business ambitions and Collingwood’s moral unease positions him as a necessary cog in the machinery of exploitation—an officer who ensures that commerce and cruelty sail in unison.

Robert Stubbs

Robert Stubbs is portrayed as the embodiment of greed, corruption, and opportunism within the colonial world. Once a governor at Anomabu, Stubbs’s downfall and subsequent alliance with Collingwood highlight the moral rot at the heart of Britain’s overseas empire.

He manipulates trade, inflates prices, and treats human lives as commodities, seeing in every transaction a chance for personal gain. His disgrace and humiliation at the hands of the Fante chiefs do little to awaken his conscience; instead, he clings to the remnants of influence by joining the Zorg’s voyage.

In the ensuing legal trials, Stubbs reemerges as a witness whose testimony is riddled with self-interest, dramatization, and deceit. His character demonstrates how corruption is not merely a byproduct of empire but its lifeblood—sustaining itself through lies, greed, and complicity.

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp stands as a moral counterweight to the system that produced men like Gregson and Collingwood. A modest London clerk turned activist, Sharp channels quiet persistence into transformative moral energy.

His journey from helping the beaten youth Jonathan Strong to challenging the entire legal framework of slavery reveals a man guided by faith, principle, and intellect. When he learns of the Zorg massacre, his outrage becomes a defining moment in Britain’s abolitionist awakening.

Sharp’s insistence that the killings constitute murder rather than property loss reframes the discourse on slavery from economics to ethics. He operates not through violence or rhetoric but through the disciplined power of law and documentation.

Sharp’s legacy in the narrative is that of conscience made institutional—a reminder that individual conviction, when persistently applied, can shift the moral compass of a nation.

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano brings a voice of lived experience and moral clarity to The Zorg. A former enslaved African who endured the Middle Passage, purchased his freedom, and became an eloquent advocate for abolition, Equiano’s appearance in the narrative transforms historical documentation into personal testimony.

His reading of the anonymous letter about the massacre and his decision to bring it to Granville Sharp serve as the crucial bridge between atrocity and action. Through him, the story transcends the courtroom and enters the public conscience.

Equiano’s humanity contrasts starkly with the dehumanization practiced by men like Collingwood and Gregson. His very existence undermines the racist assumptions on which slavery was built, proving that intellect, morality, and courage know no color.

In the broader arc of the novel, Equiano embodies survival, witness, and the power of truth.

Kojo and Sia

Kojo and Sia, though partially fictionalized, personify the millions of voiceless Africans who endured capture, transport, and death in the transatlantic slave system. Kojo’s forced march from the Sahel to the Gold Coast, his repeated sale through layers of African and European traders, and his eventual imprisonment in the Zorg’s hold illustrate the scale and cruelty of the trade’s logistics.

His suffering is not individualized for sentimentality but presented as emblematic of collective trauma. Sia, the pregnant woman noted among the Zorg’s captives, symbolizes both the generative and destructive aspects of humanity under bondage—the life within her juxtaposed with the death surrounding her.

Together, they serve as the emotional core of the narrative, grounding the historical analysis in human pain. Through Kojo and Sia, The Zorg restores identity and dignity to those reduced to statistics, transforming the massacre from abstraction into remembrance.

Themes

Greed and the Dehumanization of Commerce

The narrative of The Zorg exposes how the pursuit of profit transformed human lives into mere commodities. The entire machinery of the Atlantic slave trade—its ports, merchants, captains, and financiers—was governed by a system that valued economic gain above moral or human consideration.

The detailed accounts of Liverpool’s rise as a trading hub reveal a city whose prosperity was literally built upon human suffering. The merchants’ ledgers replaced empathy with arithmetic; human beings were categorized not by name or story but by physical fitness and resale value.

This reduction of life to ledger entries reached its grotesque zenith aboard the Zorg, where enslaved Africans were thrown overboard to protect insurance claims. The justification that such killings were “necessary for the safety of the ship” underscores how greed had annihilated moral perception.

The law itself, structured to safeguard property rather than people, became complicit, turning mass murder into an accounting dispute. Through this, Siddharth Kara reveals that economic systems built on exploitation erode humanity not only in their victims but also in their perpetrators, who lose their capacity for conscience and empathy.

Greed here functions not merely as individual corruption but as a societal ethos, infecting commerce, governance, and even faith, until cruelty becomes rationalized as necessity.

Law, Morality, and the Corruption of Justice

The Zorg demonstrates the profound moral dissonance between legality and justice in eighteenth-century Britain. The trials that followed the massacre aboard the ship expose a legal system more concerned with property rights than human rights.

When the deaths of 132 Africans were discussed in court, the debate centered not on murder but on insurance liability. Lawyers, judges, and merchants treated lives as goods whose loss could be compensated in pounds.

The courtroom scenes reflect a society where law had been bent to serve commerce, and morality had been displaced by technical argument. Yet within this corruption, Kara also portrays the emergence of conscience through figures like Granville Sharp and the anonymous letter writer who reframed the case as a moral outrage.

Their voices transformed the language of legality into a discourse of humanity, insisting that law without justice is tyranny. The conflict between the courtroom’s cold rationality and the moral clarity of abolitionists captures a transitional moment in Western thought: when society began to question whether legality could excuse evil.

The narrative thereby becomes a study in how systems of justice can sustain atrocity through language and procedure, and how moral courage is required to rehumanize the law.

Suffering and Resistance of the Enslaved

Amid the vast machinery of oppression, The Zorg restores attention to the endurance and resistance of the enslaved Africans. Through the imagined figures of Kojo and Sia, the book reconstructs the human cost of capture, transport, and bondage.

These individuals endure chains, marches, branding, and confinement, yet their continued survival asserts a form of defiance. Their stories highlight the continuity of suffering—from the Sahel’s slave raids to the dungeons of Cape Coast Castle and finally to the suffocating holds of the ship.

Each stage reduces them to objects, yet they resist erasure through memory, through acts of self-preservation, and even through suicide, which becomes the final assertion of agency. The women, often subjected to sexual violence, bear another dimension of endurance, surviving both physical and psychological degradation.

Kara’s reconstruction gives voice to those silenced by history, demonstrating that resistance existed not only in rebellion but also in endurance, in the will to survive and remember. This theme reclaims individuality from anonymity, restoring moral weight to those whom history recorded only as numbers.

The enslaved become not victims of circumstance but witnesses to the enduring capacity of the human spirit under absolute oppression.

The Birth of Conscience and the Rise of Abolitionism

The aftermath of the Zorg massacre marks the awakening of Britain’s moral consciousness. The anonymous letter that condemned the killings became a moral lightning strike across society, forcing readers to confront their complicity in a system they had long accepted as commerce.

Figures such as Olaudah Equiano and Granville Sharp embody the transformation of outrage into activism. Equiano’s personal suffering became the emotional bridge between the public and the enslaved, while Sharp’s insistence on legal accountability gave structure to moral protest.

The alliance of these figures, one speaking from lived horror and the other from moral conviction, represents the union of empathy and reason that would give rise to the abolitionist movement. Kara portrays this awakening not as a sudden revelation but as the painful emergence of a collective conscience from centuries of denial.

The massacre, once an obscure legal case, became the emblem of moral failure and the catalyst for reform. The theme thus captures a turning point in human history—the realization that progress and civilization cannot coexist with inhumanity, and that conscience, once awakened, can reshape nations.

Power, Race, and Historical Memory

The Zorg interrogates how race and power determined who was remembered and who was erased. For centuries, the atrocity of the Zong was misrecorded—even its name distorted—revealing how history itself becomes complicit in oppression.

By restoring the ship’s true identity and reconstructing the lives aboard it, Kara performs an act of historical justice. The narrative shows how racial hierarchy justified not only slavery but also the selective preservation of memory.

The British merchants’ names—Gregson, Hanley, Collingwood—survive in archives and court documents, while the Africans remain faceless except for a few symbolic figures. This imbalance of remembrance mirrors the broader structure of imperial history, where the oppressor’s narrative dominates the record.

Kara’s work thus challenges the reader to confront how power shapes truth, how archives conceal as much as they reveal, and how reclaiming forgotten names is itself an act of resistance. The restoration of “Zorg” over “Zong” becomes symbolic of reclaiming accuracy, identity, and accountability from centuries of distortion.

In doing so, the book not only recounts a tragedy but also redefines how history must be written—by restoring the humanity of those whom the past sought to erase.