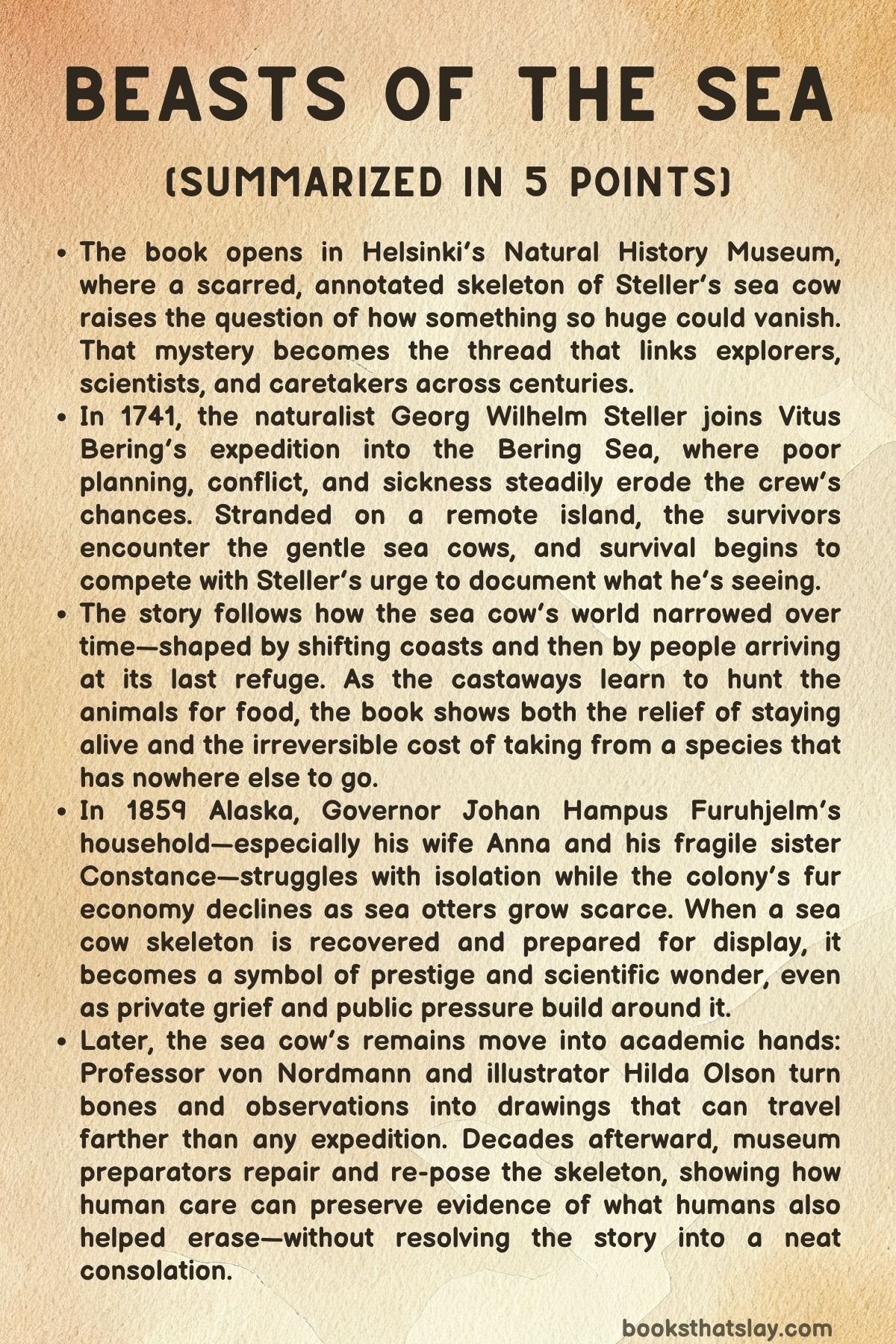

Beasts of the Sea Summary, Characters and Themes

Beasts of the Sea by Iida Turpeinen is a novel about an animal that is gone, and the people who briefly lived close enough to touch the edge of its world. It begins with a modern visitor staring at the marked, battered skeleton of Steller’s sea cow in Helsinki’s Natural History Museum, then moves across centuries to show how that skeleton came to exist at all.

The book follows explorers, colonists, scientists, artists, and conservators—people driven by hunger, ambition, curiosity, and fear—as they encounter abundance, loss, and the long afterlife of extinction.

Summary

A visitor enters the Natural History Museum in Helsinki and finds a strange exhibit among familiar bones: a massive, cracked skeleton, covered in handwritten numbers and old labels. Children guess it is a dinosaur, but the tag identifies it as Steller’s sea cow.

The sight of its size and damage suggests a long journey, and the story rewinds to the Bering Sea in 1741, when the animal still lived.

On the Kamchatka Peninsula, Captain Commander Vitus Bering prepares a state-backed voyage meant to chart waters between Asia and the Americas. Two ships, the St Peter and the St Paul, gather with sailors, officers, and an intended scientific team.

That team, worn down by years of brutal travel and setbacks in Siberia, gives up and returns west, leaving the expedition without its researchers. Georg Wilhelm Steller—an outspoken theologian-naturalist who has endured Siberia and wants to push farther—takes their place, arriving by dogsled and quickly clashing with the expedition’s leadership.

The departure drags on for months. Supplies go missing, deliveries fail, and arguments consume time.

Steller waits, complains, and studies local fish while the ships sit in cold uncertainty. When they finally sail on June 4, the weather turns against them.

In fog and drizzle the two ships separate and never reunite, leaving the St Peter short of provisions. Steller tries to advise the officers using his observations of currents, seaweed, and birds, but he is ignored.

He watches them calculate positions incorrectly and sees the voyage slide into confusion. During the crossing he notices a playful red-furred sea creature and orders a marksman to shoot it, hoping to secure proof.

The animal escapes, and the mystery stays unresolved.

After weeks at sea, water grows scarce and the officers agree to turn back if land does not appear. On July 20 the St Peter starts home—only for a lookout to spot land.

They anchor near a green island on St Elias’ Day and name the place Cape St Elias, despite Steller’s objections to their certainty about where they are. Bering, exhausted and ill, remains aboard.

Steller fights for time ashore and wins only a brief trip to fetch fresh water. On land he finds unfamiliar birds and evidence that people have stored supplies there.

He takes an arrow, flint, and a strap of seagrass, leaving trade goods behind as payment. He returns furious that the expedition has reached the Americas only to fill barrels, and Bering insists they depart immediately.

The homeward journey becomes a collapse. Winds and island-clogged seas slow them, barrels leak as hoops rot, and rations thin.

Scurvy spreads. Men’s gums bleed, teeth loosen, and bodies fail.

Deaths increase, recorded with grim regularity. On November 5 a shoreline appears through rain.

Steller doubts they are at Kamchatka, but the crew is desperate and anchors anyway. A night gale snaps their cables, and in panic they throw stored corpses into the sea to lighten the ship.

The St Peter is driven into shallow water and breaks apart. Survivors reach an uninhabited shore that they do not yet understand.

They build a rough camp in pits roofed with sailcloth. Sea otters are so tame that they can be killed easily, and the men roast them for food.

Arctic foxes raid the camp, biting the sick, and the crew responds with escalating cruelty. Three of the least ill men go to seek help, but none comes.

Steller tries to salvage preserved specimens from the wreck, but seawater ruins chemicals and destroys much of his work. As hunted animals grow wary, hunger returns.

Exploring the shore, Steller finds an enormous plant-eating sea mammal grazing on kelp in the shallows—giant sirenians that will later be known as Steller’s sea cows. Bering dies on December 8 and is buried deep to keep foxes away.

A bleak Christmas follows, and scouts confirm the worst: they are stranded on an unknown island, beyond rescue. The book pauses to explain how the sea cow’s ancestors once ranged widely along Pacific coasts, then were pushed into smaller habitats by changing seas, leaving a final vulnerable population near the Aleutians.

For the survivors, the sea cow becomes food and hope. The first attempts to kill one fail: bullets bounce off its thick hide, and carcasses can sink before they can be hauled in.

The crew refines a plan using harpoons and ropes. When they finally spear a young animal and wedge it against rocks, the herd gathers nearby as the wounded sea cow cries.

A midshipman finishes it with an axe. The starving men rush into freezing water to climb onto the animal’s back and end it quickly.

Onshore they cut it open, melt blubber into hot fat, and eat until pain replaces hunger. Warm blood, roasted flesh, and organs restore them.

Within days, scurvy eases: gums tighten, strength returns, and men who seemed near death begin to stand again.

Steller, relieved to see recovery, hopes to study the carcass scientifically, but the crew hacks it apart for food. In spring the island fills with birds, and he watches sea cows courting and mating, recording careful notes.

The narrative also shows Steller’s marriage to Brigitta-Helena in St Petersburg and the strain of his Siberian assignment. She begins the journey east but turns back in Moscow, unable to endure it, while Steller continues alone, bitter and increasingly isolated.

With no rescue coming and winter certain to return, the acting leader, Waxell, offers the forty-six survivors a choice: stay and die, or dismantle the wreck and build a new vessel. They choose construction.

Hope rises, along with gambling and a new obsession with pelts. Foxes and otters are killed in staggering numbers as the men imagine profit and redemption.

Steller wants a proper specimen and arranges for a female sea cow to be brought in. He dissects it with crude tools, bribing assistants with tobacco, measuring organs and searching for legendary stones said to exist inside manatees.

Finding none, he tries to prepare the skeleton, hiding bones around camp and working almost alone. By August the crew completes a small boat, the Hooker St Peter, barely large enough to carry essentials.

Steller must abandon his collections and the sea cow bones, taking only his notes and a pipe carved from a bird bone. They launch on August 13, cramped and afraid, and reach Avacha Bay on August 27 to the astonishment of those who assumed them dead.

Back on Kamchatka, Steller refuses a sea journey and travels west through Siberia, collecting plants and seeking rumored mammoth remains. His path tangles with colonial politics: he is drawn into interrogations, angers officials, and is ordered to face treason charges.

Though testimony later clears him, the stress and illness break his body. He dies near Tyumen on November 12, buried quickly, his grave later robbed, and his wife never properly informed.

The story shifts to Alaska in 1859. Professor Alexander von Nordmann arrives seeking the legendary sea cow.

Governor Johan Hampus Furuhjelm, pressured to restore a failing fur economy, has married Anna Elisabet von Schoultz and brought her to Sitka. Anna’s long trip ends in isolation, depression, and a struggle to keep her infant daughter alive.

A Yupik wetnurse is found, monitored and controlled, and Anna’s household grows tense, especially with the presence of Hampus’s fragile sister, Constance. As sea otters vanish and the colony frays, Constance is given a new purpose: managing the governor’s zoological collection of dead specimens and artifacts.

In that silent room she finds calm and competence. A German taxidermist, Martin Wolff, is hired to modernize the collection, and Constance learns, catalogs, and changes in ways that unsettle the household’s fragile balance.

A discovery electrifies the colony: Aleut men find a largely intact sea cow skeleton on Bering Island and bring back the skull as proof. Wolff cleans and numbers the bones under supervision, while Constance watches with fierce attention and presses for anatomical understanding.

Hampus hopes the mounted skeleton will impress officials from St Petersburg and prove Alaska’s value, yet the delegation remains unimpressed. Constance’s health collapses, and after a severe seizure she dies.

Anna arranges her burial with care, shocked by her own grief. Soon after, Kekoor Castle burns, destroying much of the collection.

Russia sells Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million, and the sea cow skeleton is shipped to Helsinki.

In 1861, von Nordmann’s failing eyesight leads him to hire a young illustrator, Hilda Olson, whose precision with tiny spiders proves her skill. Their partnership produces hundreds of scientific drawings.

When the sea cow skeleton arrives at the university, Hilda is tasked with drawing its bones as scholars reconstruct the frame and replace missing parts with carved wood. Von Nordmann speaks publicly about extinction caused by humans, insisting the sea cow’s disappearance is not a myth but a warning.

Years later he dies suddenly, and Hilda, blocked by sexist institutions, loses opportunities and even proper credit for her work. She survives by copying legal documents until a chance offer from England brings her to London, where she designs wallpaper patterns and quietly hides spiders in the flowers as a private signature.

Time advances again. Museum collections consolidate, and the sea cow’s bones remain a prized exhibit.

In the mid-1900s, preparator John Grönvall restores specimens and is hired to repair a cracked great auk egg, another relic of a vanished species. His youth is marked by efforts to protect seabirds, and his adult life becomes a form of repair work for damage humans have caused.

He restores the sea cow skeleton, correcting earlier mistakes and giving it a more natural posture, keeping the animal’s form present even as its living world is gone.

The book returns to the museum in the present day. An elderly woman stands before the sea cow’s skeleton, surrounded by rain and quiet, and feels what the bones represent: not only a lost species, but a chain of human choices—starvation and survival, commerce and vanity, study and preservation—that turned a living animal into an exhibit marked by hands across centuries.

Characters

Georg Wilhelm Steller

Steller is the book’s driving human conscience: brilliant, stubborn, and relentlessly observant, he treats the living world as something to be known accurately rather than conquered quickly. His intellect is matched by a rough-edged temperament—he complains, argues with officers, and refuses to flatter authority—yet that abrasiveness is inseparable from his moral clarity, especially when the expedition’s vanity and incompetence turn lethal.

On Bering Island, his role expands from scientist to reluctant survivalist, forced to watch hunger and desperation convert discovery into slaughter. Even then, he keeps trying to “save” meaning from catastrophe by recording what he sees, measuring what can no longer be protected, and attempting to build a specimen out of chaos.

The tragedy of Steller is that his methods—attention, care, naming, documentation—are constantly undermined by the very human systems that brought him there: empire, command hierarchy, and scarcity-driven violence.

Captain Commander Vitus Bering

Bering embodies the expedition as a state project: cautious, burdened, and physically failing, he is less a swashbuckling navigator than a weary administrator of risk. His decisions are shaped by exhaustion and institutional pressure, and his illness becomes a metaphor for the expedition’s larger decay—once the ship is losing water, direction, and bodies, command turns increasingly into grim damage control.

He is not portrayed as purely villainous; rather, he is a man whose authority persists even when his capacity collapses, and that mismatch magnifies the crew’s suffering. His death on the island crystallizes the cost of imperial ambition: the leader who “must” reach somewhere dies in a place that isn’t even properly named, while those under him inherit the consequences.

Sven Waxell

Waxell emerges as the expedition’s practical center of gravity once the crisis hardens into long-term survival. Where others cling to rank or panic, he works in probabilities—food, shelter, labor, morale—and makes decisions that are ethically messy but collectively stabilizing, especially when the survivors must choose between waiting for death and building a new ship from wreckage.

He also represents a different kind of leadership than Bering: adaptive rather than positional, persuasive rather than purely authoritative. Yet the book does not let competence become innocence; under Waxell’s watch, survival still depends on relentless killing, and the return to “order” includes gambling, cruelty, and exploitation, reminding us that efficiency can coexist with moral compromise.

Toma Lepekhin

Lepekhin functions as the hard edge of Steller’s scientific desire: the marksman whose skill can transform curiosity into a wound, a specimen, or a meal. His presence shows how exploration depends on labor and violence that are often assigned to subordinates, allowing officers and scholars to maintain cleaner hands in theory while relying on blood in practice.

When he shoots at the strange red-furred creature, the moment captures the book’s recurring tension between wonder and possession—the impulse to understand something new immediately becomes the impulse to seize it. Lepekhin’s role is less about interior psychology than about what he represents: the human body trained to make the natural world available at a distance, through force.

Midshipman Johann Sind

Sind is most visible at the moment the sea cow becomes food, not knowledge—finishing the first kill with an axe when bullets fail and hunger overrides hesitation. He stands for the crew’s threshold-crossing, the point where desperation rewrites what is acceptable and turns a monumental animal into an emergency resource.

Even if he is not deeply individualized, his action is thematically decisive: it signals the shift from “we might survive” to “we will survive by taking,” and it initiates the pattern of consumption that both saves human bodies and accelerates extinction.

Brigitta-Helena

Brigitta-Helena’s storyline reframes exploration from the viewpoint of the person left behind, revealing how empire and science fracture private life. She is intelligent and capable—engaged with learning, conscious of social expectations—yet her marriage is shaped by Steller’s ambition and by the brutal logistics of Siberian travel.

Her refusal to continue the journey is not weakness so much as a boundary drawn against a system that treats spouses as portable attachments to male destiny. Steller’s bitterness toward her exposes his blind spot: a man who can see animals and landscapes with exactness can still fail to see another human’s limits with compassion.

Professor Alexander von Nordmann

Von Nordmann represents the later institutional phase of the story, when extinction has moved from immediate violence to curated aftermath. He is ambitious and strategically social—able to ask governors for legendary specimens and convert faraway remains into scholarly prestige—yet he is also one of the first characters to speak with clarity about human-caused disappearance.

His failing eyesight is symbolically sharp: as his literal vision dims, his intellectual vision about loss and responsibility grows more pointed, and he needs another person’s eyes and hands to keep producing knowledge. In him, the book shows a complicated continuity—science can both participate in extraction and become a language for mourning and warning.

Hilda Olson

Hilda is the book’s most vivid portrait of disciplined attention as a form of power, and of how that power is constrained by gender and institutions. Her talent is not merely artistic; it is epistemic—she makes creatures and bones legible through precision, turning small lives (spiders) and gigantic absence (the sea cow skeleton) into images that can travel where bodies cannot.

She is repeatedly confronted by male spaces that treat her presence as a disruption, and later by the theft of credit that turns her labor into someone else’s legacy. Her eventual shift into wallpaper design is not a retreat from truth but a reinvention: she hides spiders in ornamental motifs as a private act of remembrance, proving that scientific seeing can survive even when professional gates close.

Governor Johan Hampus Furuhjelm

Hampus is a political manager trapped between imperial expectations and ecological reality. He wants Alaska to “prove” its value, but the colony’s wealth depends on animals that are disappearing under pressure, and the rules of governance—bans, quotas, delegations, reputational performance—arrive too late or cut in the wrong ways.

At home, he can be tender and attentive, especially with his daughter, yet he also treats people as solutions: a wetnurse must be found, Constance must be given a role, a skeleton must impress officials. His arc shows how administration turns living systems into accounting problems, and how that mindset can deepen both domestic and environmental crisis.

Anna Elisabet von Schoultz Furuhjelm

Anna’s character reveals the psychic cost of transplantation: she moves through grand journeys and arrives in a place she cannot narrate except by describing interiors, as if controlling rooms can substitute for understanding the world outside them. Her postpartum suffering, isolation, and anxiety make her both sympathetic and controlling; she responds to uncertainty by tightening rules, monitoring others, and trying to preserve appearances.

Her relationship with motherhood is especially painful—her inability to feed Annie becomes a wound that never fully closes, and the wetnurse’s calm competence intensifies Anna’s sense of displacement. Yet Anna is also capable of real devotion, most strikingly in how she tends to Constance at the end, suggesting a deep, buried capacity for care that surfaces when performance finally becomes irrelevant.

Annie

Annie functions less as a speaking character and more as an emotional axis around which adults reveal themselves. As a baby, her fragility exposes the colony’s precariousness and forces decisions that cross cultural and moral boundaries, especially the acquisition and surveillance of the wetnurse.

As she grows, her attachment patterns—clinging to the woman who fed her, wary of Anna—become a silent verdict on what love can and cannot be willed into existence. Annie also embodies continuity amid imperial churn: while men argue over markets, specimens, and borders, her ordinary development becomes the most human measure of time passing in a place defined by extraction.

Constance Furuhjelm

Constance begins as a source of fear and inconvenience—her illness, shakiness, and “falling fits” make her the household’s unpredictable element—but she becomes one of the book’s most poignant studies of refuge. The zoological collection offers her a world that does not demand social fluency or physical steadiness, only patient attention, and she grows into a quiet competence that is both empowering and heartbreaking.

Her interest in dead specimens is not morbidity so much as safety: preserved animals cannot judge her, and labels provide a structure her body cannot guarantee. Her death, after she briefly finds purpose, underscores the book’s insistence that vulnerability is not a side plot—it is a central human condition, intensified by isolation and by systems that treat weakness as a problem to hide.

Ida Höerle

Ida is the domestic instrument of control, a figure through whom surveillance becomes routine and morality becomes enforcement. She is tasked with watching the wetnurse, guarding propriety, and maintaining boundaries, but her increasing resentment suggests how authority can poison the person made responsible for it.

Ida’s distance is revealing: she is close to every intimate crisis and yet remains emotionally shut out, as if constant policing prevents genuine care. Through Ida, the book shows how households can mirror colonial administration—monitoring bodies, regulating contact, and turning dependence into suspicion.

The Yupik wetnurse

The wetnurse enters as necessity rather than choice, and the rituals imposed on her—washing, cutting hair, burning clothes, constant monitoring—make her the clearest symbol of colonial power operating at the level of the body. Yet she is not depicted as merely passive; her calm presence and soft singing suggest a steadiness that quietly outlasts the household’s panic.

Her bond with Annie highlights an uncomfortable truth: the most life-giving relationship in the house is also the one most constrained, controlled, and ultimately disposable once the crisis passes. She embodies how indigenous labor sustains colonial families while being denied dignity, privacy, and permanence.

Martin Wolff

Wolff is a professionalizer of death: a taxidermist hired to modernize a collection and convert animal remains into display, status, and persuasion. He is opportunistic and socially aware—briefly considering courtship as strategy—yet he is also a craftsman whose work depends on close knowledge of bodies.

His warnings about extinction are unsettling precisely because they come from someone whose career thrives on the afterlife of animals; he senses the pipeline is running dry. Wolff illustrates the book’s moral ambiguity around preservation: to mount a skeleton is to honor it and to advertise the system that erased it.

Hjalmar Furuhjelm

Hjalmar represents the colonial fantasy in its most self-deceiving form: he romanticizes native life while exploiting it, performs benevolence while trafficking in forbidden goods, and mistakes impulse for righteousness. His mining venture is both economically incompetent and socially corrosive, producing rumors that expose how quickly “civilized” narratives collapse into scandal when power is unchecked.

By bringing home a Yupik girl under the story of rescue, he reveals the violent entitlement that often hides inside sentimental talk about saving others. Hjalmar’s presence darkens the domestic plot by showing how the colony’s private harms and public extraction share the same root: treating people as possessions.

Otto Edvin

Otto Edvin is a brief but symbolically heavy figure: the son whose birth is supposed to stabilize lineage and relieve anxiety, yet whose arrival cannot erase the household’s fractures. Anna’s pride in nursing him, after failing with Annie, makes him a vessel for repaired identity—a second chance at the motherhood she felt denied.

At the same time, his relative narrative silence emphasizes the book’s pattern: children are not causes of change so much as mirrors reflecting adult hopes, fears, and the stories they tell themselves to endure.

Professor Bonsdorff

Bonsdorff stands for collection as legacy and for the uneasy desire to control what happens after death—both one’s own and that of the animals one preserves. His insistence that his skeleton collection not be merged is a demand for posthumous integrity, as if identity can be protected by organizational rules.

In old age, his awareness of mortality turns the museum into a moral space: a place where bones are both evidence and reminder, and where the boundaries between scientific order and human vanity blur.

Professor von Wright

Von Wright appears as a builder of institutional meaning, involved in reconstructing the sea cow skeleton with the practical compromises that museums require. The crafted wooden substitutes used to fill missing bones highlight a key theme he embodies: knowledge is often an engineered structure, not a perfect recovery of truth.

His work suggests that preservation is always partly interpretation, and that what visitors call “real” is frequently a collaboration between remains and human invention.

Botanist von Steven

Von Steven offers a rare interlude of mythic framing, linking Hilda’s observational craft to the story of Arachne and turning scientific illustration into a modern form of weaving. He functions as a bridge between disciplines—botany, folklore, art—implying that extinction and transformation are not only biological facts but also cultural narratives we use to understand loss.

By giving Hilda that story, he validates her work as something older and larger than academic permission.

John Grönvall

Grönvall is the custodian of the book’s late-stage ethics: a restorer whose vocation is to repair what human desire has damaged, even though repair can never resurrect. His youth as a bird lover who helps protect an island reserve shows him as someone who moves from admiration to responsibility, and his later mastery with eggs and bones turns patience into a kind of moral practice.

When he corrects earlier display errors on the sea cow skeleton, he is not just improving a specimen—he is arguing that the dead deserve accuracy, that even absence should not be distorted for convenience. Grönvall’s life suggests a quieter alternative to conquest: careful maintenance, humility before materials, and the refusal to let greed be the last touch on an extinct world.

Ragnar Kreuger

Kreuger embodies the collector’s paradox: he treasures rare objects born of destruction and is willing to pay for restoration that keeps that destruction beautiful. His commission to repair a great auk egg ties him to the pattern of extinction-as-luxury, where rarity increases value after life is gone.

Yet his patronage also funds preservation, showing how the same impulses that harm can later support conservation—without erasing the original violence. Kreuger’s role helps the book ask an uncomfortable question: when we preserve remnants, are we honoring lost life or curating trophies of our own appetite?

Steller’s Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)

The sea cow is the book’s central “character” in the sense that it is the constant presence shaping every era—first as living abundance, then as salvation, then as specimen, then as exhibit, and finally as absence made visible through bones. In the survival narrative, the sea cow exposes the cruel logic of desperation: it saves starving men and simultaneously becomes the hinge on which extinction swings.

In the museum narrative, it becomes an argument rendered in anatomy—a massive body reduced to numbered fragments, reconstructed with care, and marked by the human urge to catalogue what we have already destroyed. The sea cow’s changing form across the story—animal, meat, skeleton, icon—turns it into the book’s moral mirror, reflecting how humans translate life into use, use into knowledge, and knowledge into mourning.

Themes

Human Relationship with Nature

In Beasts of the Sea, the relationship between humans and nature unfolds as a reflection of curiosity, conquest, and remorse. From Steller’s voyage to the modern museum visitor, the narrative captures humanity’s shifting role—from explorer to destroyer to restorer.

Steller embodies the era’s Enlightenment ideal of knowledge through observation, yet his scientific curiosity is inseparable from violence. His discovery of the sea cow comes at the price of its suffering, and his dissections, while aimed at understanding, foreshadow extinction.

The sailors’ desperate slaughter of sea cows for survival transforms scientific wonder into consumption, highlighting how necessity and greed erode boundaries between preservation and destruction. In later centuries, figures like von Nordmann and Hilda Olson engage with nature differently—through documentation and art—but they, too, depend on the remnants of life already lost.

The sea cow’s skeleton, cleaned and catalogued, becomes a relic of both discovery and disappearance. The novel’s closing scenes in the Helsinki museum underscore the paradox of human reverence for what humanity itself has annihilated.

Nature is thus portrayed not merely as an external environment but as a mirror reflecting moral and historical truths about human desire, ignorance, and the longing to immortalize what has vanished.

Knowledge, Science, and Legacy

The pursuit of knowledge in Beasts of the Sea spans centuries, linking explorers, scientists, and artists in an unbroken chain of observation and recording. Steller’s meticulous notes, written amid hunger and death, are the first link—knowledge carved out of chaos.

His successors, from von Nordmann to Hilda Olson, inherit both his spirit and his burden, transforming bones and specimens into repositories of understanding. Yet Turpeinen questions whether knowledge ever truly redeems destruction.

Scientific progress is shown as cumulative but also exploitative, dependent on colonial expansion and the appropriation of nature and indigenous labor. The act of naming species, preserving skeletons, and illustrating anatomy serves both enlightenment and domination.

Hilda’s art introduces a moral dimension to this pursuit—her drawings capture not just structure but vitality, suggesting that the human eye can record beauty even in death. By the twentieth century, the taxidermists and restorers continue this lineage, preserving fragments of lost species to keep memory alive.

Knowledge in the novel is thus double-edged: it rescues what it ruins, preserves what it kills, and in doing so, becomes a record of both triumph and guilt.

Colonialism and Power

Colonial ambition threads through every generation in Beasts of the Sea, shaping lives and landscapes alike. The early expeditions to the Bering Sea are state-backed enterprises of empire disguised as scientific missions.

Steller’s ship carries not only explorers but agents of conquest, whose mapping and cataloging serve imperial control as much as curiosity. The Russian colonization of Alaska later transforms exploration into governance, as the Furuhjelm family presides over a world built on exploitation—native hunters driven to exhaustion, animals exterminated for fur, and women confined within domestic and political expectations.

Anna’s isolation in Sitka reflects how colonialism traps even its own administrators within emotional and moral paralysis. Indigenous lives appear mostly through their absence—their silence haunting the narrative like the vanished herds of sea cows.

The extinction of species parallels the erasure of native cultures under imperial rule. Power, in Turpeinen’s vision, is sustained through classification and ownership: of land, of bodies, of bones.

Even the sea cow’s skeleton, transported to Helsinki as scientific treasure, is an artifact of empire—a reminder that conquest survives not only in territories but in museums, archives, and the stories nations choose to tell about themselves.

Gender and the Margins of History

Across its centuries-spanning narrative, Beasts of the Sea foregrounds women whose lives orbit the male world of exploration and science yet whose experiences reveal the unseen costs of progress. Brigitta-Helena, Anna, Constance, and Hilda each embody different facets of constraint and resilience within patriarchal and colonial frameworks.

Brigitta-Helena’s abandonment marks how ambition can consume domestic bonds; Anna’s slow suffocation in Sitka exposes how empire’s domestic front mirrors its oppressive hierarchies; Constance’s tragic devotion to taxidermy becomes both her liberation and undoing. Hilda Olson represents a fragile breakthrough—a woman who earns intellectual recognition through her craft but is later erased from authorship.

Her story illustrates how women’s labor in science and art has historically been made invisible, even as it sustains the very knowledge systems that exclude them. Through these women, Turpeinen reconstructs the emotional archaeology of history, showing that the pursuit of discovery has always depended on unseen female endurance.

The recurring motif of observation—whether through microscopes, drawings, or diaries—becomes a metaphor for women’s quiet acts of preservation, resisting erasure through attention, patience, and care.

Extinction and Memory

Extinction is the moral and emotional axis of Beasts of the Sea, binding past and present in an unending reckoning. The Steller’s sea cow, hunted to disappearance within decades of its discovery, becomes both a literal and symbolic monument to loss.

Each era confronts its absence differently: Steller sees it as sustenance and study, von Nordmann as scientific curiosity, Grönvall as restoration, and the modern museum visitor as mourning. The novel portrays extinction not as a singular event but as a continuum—species vanish, empires collapse, knowledge fades, yet memory persists in fragments.

Museums, drawings, and preserved skeletons act as vessels of remembrance, their stillness charged with moral weight. The persistence of the sea cow’s bones across centuries evokes the tension between decay and preservation, between forgetting and responsibility.

Turpeinen suggests that remembering extinction is an act of conscience—a recognition that every preserved specimen carries both wonder and guilt. The closing image of the elderly woman standing before the skeleton encapsulates the novel’s haunting question: what does it mean to remember life only after it is gone?

Extinction, in this sense, is not just the end of species but the measure of human failure—and the fragile hope that memory might still redeem what history has consumed.