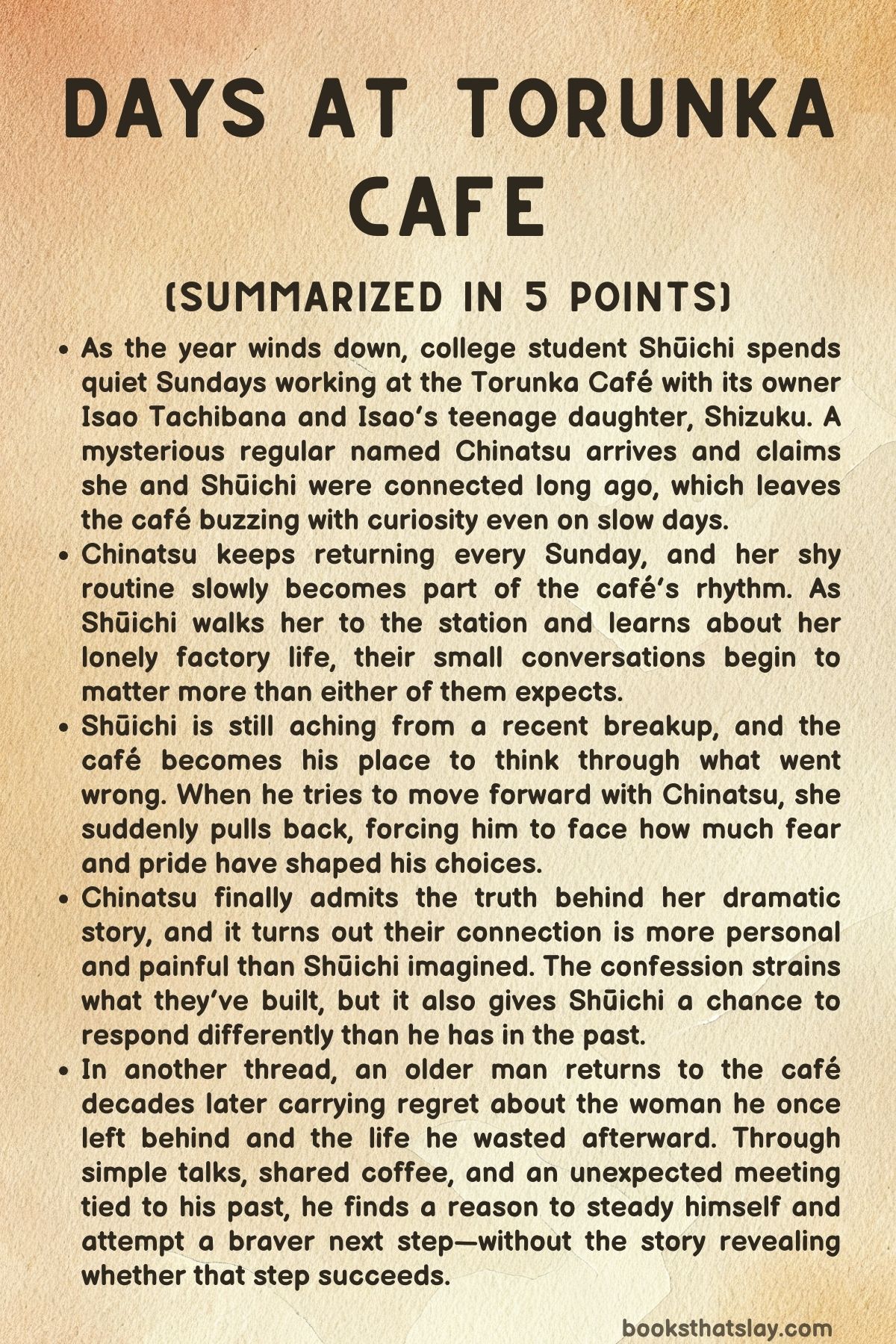

Days at the Torunka Café Summary, Characters and Themes

Days at the Torunka Café by Satoshi Yagisawa is a quiet, character-led novel set around a small Tokyo coffee shop where people keep arriving with unfinished business. Across connected stories, the café becomes a place where strangers turn into regulars, old choices surface, and new ones begin.

A part-time worker nursing a breakup meets a woman whose strange confession hides a long-kept truth. A man returns after decades to face the love he abandoned. And a café owner’s teenage daughter learns what it means to step out of someone else’s shadow and grow into herself.

Summary

Near the end of the year, Shūichi Okuyama spends a slow Sunday working at the Torunka Café with the owner, Isao Tachibana, and Tachibana’s high school daughter, Shizuku. With no customers and only music and a ticking clock to fill the room, Shizuku pokes fun at Shūichi’s aimless college life.

The quiet breaks when a young woman in a black coat and a scarlet scarf walks in and orders Colombian coffee. When Shūichi serves it, she suddenly grabs his hands and announces that they have finally met again.

She introduces herself as Chinatsu Yukimura and insists that, although they have never met in this life, they were lovers in a past one during the French Revolution—she as a man named Etienne and Shūichi as a woman named Sylvie. Shizuku is delighted by the drama, while Tachibana listens with amused patience and Shūichi stands frozen, unsure what to make of it.

The café closes for the holidays, and Shūichi spends New Year’s alone in his apartment, passing time by making coffee and circling back to thoughts of Megumi, the girlfriend who ended their relationship three months earlier. His mind returns to the day he first discovered Torunka Café: he and Megumi followed a cat down an alley and stumbled into the shop by chance.

That day became the start of their relationship and eventually Shūichi’s part-time job at the café. Now, with Megumi gone, he tells himself she will never come back, and the café feels like one of the few steady things he still has.

When the café reopens, Chinatsu returns, calmer and more courteous, bringing sweets as a gift. She explains she lives nearby and also found the café by chasing a cat, which unsettles Shūichi because it mirrors his own story.

After that, she begins visiting every Sunday. She sits quietly with her coffee and children’s books, speaking little unless Shizuku is present and pushes her to talk about her “past life.” Shūichi avoids that topic, but he learns practical details about her: she is twenty-four, works at an automotive assembly plant, and has a hard time fitting in.

She has been fired before and carries a constant worry that she will be cast out again. Shūichi, moved by her sincerity, starts making her coffee himself instead of treating her like just another customer.

One day after she leaves, Shizuku finds a napkin folded into a ballerina and insists it looks strangely lifelike. Soon the folded figures appear again, and Shizuku begins collecting them in a tin as if they are small clues to Chinatsu’s inner world.

Over the weeks, Shūichi and Chinatsu develop a quiet routine. After Sundays at the café, they often walk together to the station.

Shizuku, acting like a watchful younger sister and matchmaker at once, makes sure Shūichi escorts Chinatsu when it’s dark. Neighbors tease him about “dates,” and Chinatsu notices small habits—like the way he rubs his ear when he’s nervous.

During one walk, Shūichi talks about his childhood in Wakayama and his father’s cruelty. He describes being dragged along when his father visited a girlfriend, then left outside to wait like an inconvenience.

Chinatsu tries to lighten the weight of it by teaching him a silly phrase to shout at the station: “Let’s keep going with zero accidents!” He feels embarrassed, yet the ritual oddly steadies him, as if putting words to the day gives him a little control.

By Valentine’s Day, Shizuku is certain Chinatsu will bring Shūichi chocolates. Chinatsu arrives late, soaked from snow, and hands him homemade chocolates anyway.

The moment shifts the tone between them. Shūichi begins thinking about asking her out, and by March he finally does.

Chinatsu reacts badly—uneasy, closed off, almost frightened—and then pulls away. The next Sunday she asks to talk and leads him to a park, where she admits the French Revolution story was a lie.

The truth is closer and more painful: they met as children.

Chinatsu explains that her mother was the woman Shūichi’s father visited. When his father came over, both children were left outside together.

Chinatsu tried to protect Shūichi from the humiliation and fear of waiting by distracting him with imaginative stories, building a small private world where he wasn’t alone. She once hoped he might become her “little brother,” but then his father suddenly stopped coming, and Shūichi disappeared from her life.

Years later, as Chinatsu’s mother neared death, Chinatsu sought out Shūichi’s father, desperate to learn what happened to the boy she remembered. She discovered Shūichi was in Tokyo, working at a café in Yanaka.

Chinatsu moved to Tokyo, took factory work, and spent nearly a year wandering cafés on Sundays until she finally found Torunka. She invented the reincarnation story because she couldn’t bear saying the real reason she came looking for him.

After confessing, she apologizes and runs, deciding she won’t return.

The café’s Sundays go quiet again, and Shizuku is openly disappointed. Shūichi realizes he cannot accept Chinatsu choosing the ending alone.

After work, he goes to her factory, finds her among the workers, and asks her directly to go out with him. She agrees, and he brings her to Torunka after hours with Tachibana’s permission.

Over coffee in the closed shop, Shūichi admits he is angry not because she lied, but because she tried to disappear without letting him respond—something he recognizes in his own behavior with Megumi. Chinatsu reveals that Shūichi’s father visited her mother in the hospital and helped with medical costs, carrying shame about how he treated his son.

Shūichi, still wounded, apologizes for his father anyway and admits he may face him someday. When Shūichi asks if he once called her “Chi-chan,” Chinatsu breaks down and confirms she called him “Shū-chan.” He tells her he loves her and asks her not to vanish again.

They repeat their shared phrase—“Let’s keep going with zero accidents”—and Shūichi moves to brew fresh coffee as their earlier cups sit forgotten.

In another thread, a man returns to the same café after thirty years, remembering it as Nomura Coffee. He finds the place renamed Torunka Café, the old owner gone, and Tachibana behind the counter.

The visit awakens memories of Sanae, the woman he loved in his youth and abandoned when his hunger for success outweighed his ability to stay. He recalls falling for Sanae’s steady kindness, sharing her small apartment, and making Nomura Coffee their place.

Then he chose ambition, entered a shady business, and left her one night without looking back, telling himself it was for her good. His later life became a chain of bad decisions—marrying for status, enduring a cold marriage under pressure, and numbing himself with alcohol until he lost almost everything.

He eventually hired an investigator to find Sanae and learned she had died of cancer, leaving a daughter named Ayako. That name becomes his reason to quit drinking and rebuild.

Now sober, he becomes a regular at Torunka and meets Ayako by chance. She works at a flower shop, helps at the café, and carries her mother’s warmth in her laughter and habits.

They grow close through ordinary conversations over coffee. He hides who he is and also hides the seriousness of his health, even as heart trouble catches up with him.

After collapsing, he is told a risky surgery is his best chance. Afraid, he considers leaving quietly, but a dream of Sanae pushes him back toward courage.

When he tries to say goodbye, Ayako appears with gifts: an old photograph of him and Sanae that her mother kept, and a painting Ayako made of him with a pink flower meant to wish for reunions. Holding these, he boards the train with a vow to return.

Shizuku’s own story runs alongside these adult regrets and second starts. Named after coffee by her father, she grows up in the café but hates coffee after tasting it as a child and having a terrifying nightmare that left her afraid of its bitterness.

As a teenager, she helps at Torunka, trades easy talk with Chinatsu, and bickers with her childhood friend Kōta. With the anniversary of her older sister Sumiré’s death approaching and her mother returning from abroad for the memorial, Shizuku feels both grief and the pressure of relatives’ expectations.

A chance meeting with Ogino, Sumiré’s former boyfriend, stirs old memories. Shizuku mistakes her longing for her sister—and for the past—for romantic love, and she begins wearing Sumiré’s clothes, trying to become someone “older” and more like the sister she lost.

Kōta confronts her, angry that she’s erasing herself. Later, advice from Ayako echoes the same message: stop forcing yourself into someone else’s shape.

Shizuku finally meets Ogino in her own simple clothes and confesses. He gently rejects her, saying he cares for her as a younger sister and already has someone else.

The rejection hurts, but it also clears her vision. She realizes what she wanted was not Ogino himself, but a way to touch the part of her life that ended with Sumiré.

Kōta, waiting for her afterward, helps her cry it out, and they reconcile. After the memorial, Shizuku decides to live as herself rather than as a shadow of her sister.

Riding the train home, she makes a small, brave promise: she will drink coffee again after ten years, even if it scares her, because growing up means facing what once sent you running—one steady step at a time.

Characters

Shūichi Okuyama

Shūichi begins Days at the Torunka Café in a kind of emotional suspension: he’s physically present behind the counter and competent with coffee, but inwardly he’s drifting after Megumi’s breakup and the lingering damage of a childhood shaped by a cruel, unreliable father. His default coping style is avoidance disguised as passivity—he lets Sundays happen to him, lets feelings sit unspoken, and tries to keep life small enough that nothing can hurt too much.

Chinatsu’s arrival disrupts that stasis. Even when her “past-life lover” story sounds absurd, it forces Shūichi to confront a deeper truth: he has unfinished business with loss, abandonment, and the need to be chosen.

What makes his arc satisfying is that he doesn’t become a different person overnight; he stays awkward and self-protective, but he learns to act anyway. Going to Chinatsu’s factory and asking her out is the moment he finally stops outsourcing decisions to fate, nostalgia, or fear.

By admitting his anger and recognizing how he also “disappeared” emotionally from Megumi, Shūichi becomes more honest with himself and less likely to repeat the same pattern. Even his small habits—like rubbing his ear—read as a physical tell of anxiety, and the shared phrase about “zero accidents” becomes a gentle, practical spell he uses to keep moving forward.

Chinatsu Yukimura

Chinatsu is introduced as a dramatic intruder—black coat, scarlet scarf, intense gaze—yet the longer she stays, the clearer it becomes that her theatrics are armor rather than manipulation. Her reincarnation story isn’t simply a quirky belief; it is a carefully chosen mask that lets her express longing without naming the real wound: childhood abandonment and a bond formed in a humiliating, powerless situation.

Chinatsu’s defining trait is her protective instinct. As a child, she tried to shield Shūichi with stories while both were left outside by his father; as an adult, she repeats the same pattern by inventing a safer narrative to cover the truth.

Her vulnerability sits alongside a tough daily reality—factory work, job instability, isolation—which gives her softness a lived-in resilience instead of fragility. The napkin ballerinas quietly reveal her inner world: she makes something delicate and lifelike out of what’s disposable, which mirrors how she’s tried to salvage meaning from a past that felt throwaway to the adults involved.

When she confesses and runs, it’s not cowardice so much as a reflex to control the pain by leaving first. Her healing begins when Shūichi refuses to let her decide everything alone and asks to share the burden of what she carries.

Chinatsu’s story ultimately reframes love as persistence and honesty rather than grand romance—less “revolutionary lovers,” more two people choosing not to vanish on each other again.

Shizuku Tachibana

Shizuku is the emotional barometer of the café and, in many ways, its future. She’s sharp-tongued, easily bored, and thrilled by drama, but that surface liveliness hides a girl shaped by grief, family pressure, and a lingering fear that vulnerability will swallow her the way that childhood nightmare did.

Her hatred of coffee is symbolic without feeling forced: she grows up inside the scent and ritual of it, but rejects it because the first taste coincided with terror and disorientation, as if bitterness unlocked a world where safety dissolves. In her interactions with Chinatsu and Shūichi, Shizuku acts like a catalyst—she pushes conversations forward, teases truths into the open, and collects the napkin ballerinas as if gathering proof that something meaningful is happening in the quiet.

Her coming-of-age arc is tied tightly to her sister Sumiré’s shadow. When Ogino reappears, Shizuku mistakes longing for love because Ogino is a doorway back to a time when her sister was alive and her family still felt intact.

Her choice to wear Sumiré’s clothes is both a bid for adulthood and a confession that she doesn’t yet know who she is without comparison. The crucial change is that Shizuku learns to locate her value in her own “richness” rather than borrowed elegance.

By the end, deciding she’s ready to drink coffee again becomes a declaration that she can tolerate bitterness, memory, and uncertainty—and still find her way home.

Isao Tachibana

Isao is the quiet stabilizer of Days at the Torunka Café, the kind of adult presence that doesn’t demand attention but steadily makes a space feel safe. His humor is gentle, his patience unshowy, and his authority never becomes oppressive—he lets young people be messy without humiliating them for it.

That matters because many of the novel’s wounds come from adults who made children wait outside, disappear, or carry burdens alone. Isao runs the café as a refuge from that pattern.

He also models a version of masculinity that contrasts with Shūichi’s father: warm instead of cruel, steady instead of selfish, forgiving without being naïve. His willingness to loan the closed café to Shūichi for a private conversation with Chinatsu shows that he understands love isn’t only romance; sometimes it’s giving others a protected place to speak the truth.

Even when he laughs at Chinatsu’s early theatrics, it reads not as mockery but as a recognition of how people perform when they’re desperate to be seen.

Megumi

Megumi exists largely through Shūichi’s memory, which is fitting: she represents how the past can become a locked room we keep returning to, hoping the furniture has rearranged itself into a happier ending. The way Shūichi recalls meeting her—following a cat into the café—casts their beginning as serendipity, and his nostalgia makes their relationship feel like a “before” that should still be recoverable.

Yet Megumi’s absence is instructive precisely because it is ordinary; she doesn’t need to be villainous for Shūichi to be hurt. She becomes a mirror for Shūichi’s avoidance: he convinces himself she will never return, and in doing so he avoids the harder task of grieving properly and asking what he contributed to the distance between them.

The emotional lesson Megumi leaves behind is not that love ends, but that waiting for someone to come back can become an excuse not to live. Shūichi’s eventual anger at Chinatsu for deciding everything alone is also an indirect reckoning with what he never voiced to Megumi—his needs, his fears, and his tendency to retreat into silence.

Hiroyuki Yumata

Hiro, the narrator of the later story functions as a portrait of regret aging into wisdom. As a young man, he is restless, ambitious, and seduced by the idea that “success” will justify emotional harm.

He leaves Sanae the way some people leave a room they’ve decided is too small for their dreams—quickly, without looking back, and with a self-serving story about doing her a favor. His life afterward is a chain of substitutions: a status marriage instead of intimacy, alcohol instead of comfort, money instead of meaning.

What makes him compelling is that he doesn’t pretend these were misunderstandings; he calls them mistakes and lives with their consequences in his body, through illness and fear. When he returns to the café decades later, he’s not asking to rewrite history so much as seeking a place where memory can be held without destroying him.

His bond with Ayako becomes a second chance that isn’t romantic or transactional—it’s relational repair. The tenderness of his growth lies in accepting that love doesn’t always return in the form you want; sometimes it returns as responsibility, gratitude, and the courage to tell the truth before time runs out.

Sanae

Sanae is the novel’s embodiment of steady, everyday devotion—humble, practical, and quietly profound. Her love is not flashy, but it is structurally important: she builds a “home” out of scarcity, turning a small apartment and shared routines into a sense of belonging.

She is also emotionally strong in a way that resists melodrama. When abandoned, she refuses money, as if refusing to let their relationship be reduced to compensation.

Her insistence that their greatest gift was sharing coffee at the café reframes love as lived time rather than future promises. Even after her death, Sanae’s presence remains active: she becomes the narrator’s moral compass, the memory that both accuses and saves him.

The photograph she keeps is especially telling—it suggests she did not erase him from her life, but preserved a truthful piece of the past without letting it stop her from moving forward. In that balance—remembering without being trapped—Sanae becomes the story’s quiet ideal.

Ayako

Ayako carries warmth that could have been sentimental, but the story grounds it in agency: she works hard at a flower shop, helps at the café, and pursues illustration with the stubborn optimism of someone choosing hope as a practice. She resembles Sanae in laughter and gentleness, yet she is not merely a replacement; she is the next generation translating kindness into a different era.

Her talkativeness and literary quoting give her a voice that feels self-authored, and her belief in life as worth fighting for becomes a lifeline for the narrator, who is learning how to live without numbing himself. Ayako’s most striking trait is her generosity without entitlement.

When she realizes who he is from the photograph, she does not expose him, punish him, or demand a confession; she offers him “luck,” a symbolic reunion, and a painting that turns his battered life into something worthy of color. In doing so, Ayako becomes the story’s proof that inheritance can be healing: a daughter can carry her mother’s warmth without carrying her mother’s wounds.

Mrs. Nomura

Mrs. Nomura exists as a kind of absence that still shapes space. Her café, once Nomura Coffee, becomes the physical container for memory—the furniture remains, the atmosphere shifts, and the narrator feels the ache of time in the details.

Her death marks the unavoidable fact that places change even when we want them to preserve our past intact. Yet what lingers from her is the idea of a café as sanctuary: a room where people can sit with themselves long enough to become honest.

Even when she is gone, the continuity of the shop suggests that what she built was bigger than her—an ethic of quiet hospitality that survives through others.

Tachibana (the later café owner)

The middle-aged owner named Tachibana in the later narrative reflects another kind of redemption: not the long, regret-soaked arc of the narrator, but a practical pivot away from harm. His past job in debt collection implies a life spent around pressure, fear, and coercion, and his decision to run the café instead reads like a conscious choice to become a gentler presence in the world.

The fact that he offers free coffee and conversation shows a philosophy that counters transactional living. He becomes a listener who does not pry, a steady human witness who helps the narrator feel less alone without demanding performance.

Whether or not he is directly connected to Isao Tachibana, his role continues the book’s broader pattern: the café is repeatedly saved by people who choose softness as a form of strength.

Sumiré Tachibana

Sumiré is the gravitational center of Shizuku’s grief. In Shizuku’s memories, Sumiré feels “otherworldly”—quiet, bookish, mature beyond her years—which makes her death not only a loss of a person but a loss of a certain imagined future.

Sumiré’s relationship with Ogino, and her decision to break up by saying she liked someone else, reveals a protective love that mirrors Chinatsu’s childhood protectiveness: she tries to spare someone pain by choosing solitude. That choice becomes tragic because it leaves the living with unanswered questions, and Shizuku with a longing that can attach itself to the wrong object.

Sumiré’s continuing influence is double-edged: she inspires tenderness and depth, but also tempts Shizuku into self-erasure. Shizuku’s growth requires loving Sumiré as her sister, not using Sumiré as a template for becoming “worthy.”

Ogino

Ogino arrives as a figure of suspended mourning. His avoidance after the funeral reads as guilt and fear: he associates Shizuku’s family with a moment when he lost control of himself, and staying away becomes his way of containing grief.

When he returns and drinks the coffee “unchanged,” he embodies how people search for fixed points after loss—flavors and rituals that reassure them something survives. Ogino’s pain is sincere, and that sincerity is what Shizuku mistakes for romantic possibility; she senses the depth of his love for Sumiré and tries to step into the vacancy it left.

His gentle rejection is important because it refuses to exploit Shizuku’s feelings. He treats her as someone to protect, not someone to use, and in doing so he becomes part of Shizuku’s education: longing can feel like love, but love must meet reality and mutuality.

Ogino also helps clarify Sumiré’s character—his continuing affection suggests she was deeply loved, not merely idealized by family memory.

Kōta

Kōta is the messy, vital presence that keeps Shizuku tethered to her real life while she flirts with becoming a ghost of her sister. Their bickering has the texture of intimacy built over years—automatic, unguarded, and sometimes cruel in its bluntness.

What makes Kōta valuable is that his anger is protective, not possessive. When he confronts Shizuku for wearing Sumiré’s clothes, he is essentially fighting for Shizuku’s right to exist as herself rather than as an imitation designed to win someone else’s attention.

His refusal to engage during the festival shows that he also gets hurt and doesn’t always communicate well, which prevents him from becoming a flawless “nice guy” figure. The reconciliation scene reveals his deeper loyalty: he stayed close because Sumiré asked him to look after Shizuku, and he honors that request not by controlling her, but by insisting she doesn’t abandon herself.

Kōta represents the love that’s nearby and imperfect—the kind that doesn’t sparkle like nostalgia but lasts because it’s rooted in everyday care.

Themes

The café as a shelter for belonging and continuity

A quiet shop with a familiar clock, soft music, and the repeated act of making coffee becomes the one place where people can show up as they are, even when their lives outside feel unstable. In Days at the Torunka Café, the Torunka Café is not treated like a romantic backdrop; it functions more like a steady room in a city that keeps changing, a space where the same chair, the same cup, and the same greeting can hold someone together for one more day.

Shūichi’s Sundays, Chinatsu’s careful routine, and later Hiro’s return after decades all depend on the café’s calm predictability. That predictability matters because the characters are carrying histories that are hard to speak out loud: family cruelty, loneliness, regret, grief, fear about the future.

The café allows these burdens to be present without forcing immediate explanation. People can sit with silence, or with small talk, or with a single surprising confession, and none of it has to be resolved in one dramatic moment.

Even the smallest repeated gestures—handing over a warm cup, borrowing the closed café for a private conversation, offering a free coffee to a stranger—become ways of saying “you are allowed to be here.” The shop also works as a bridge between different generations of pain and recovery: the younger characters treat it as a natural part of their week, while an older visitor experiences it like a doorway into a life he thought he had lost forever. Changes to the café—brighter light, a different owner—don’t erase what happened there; they show how a place can keep its emotional function even when its surface shifts.

The café’s real power is that it makes connection feel ordinary rather than heroic, and that ordinariness becomes the foundation for healing.

Invented stories, hidden truths, and the fear of being known

The book repeatedly shows people using stories as protection, not entertainment. Chinatsu’s past-life claim is extreme on the surface, but it fits a very human impulse: when the truth is too raw, a person may reach for a safer explanation that still communicates longing.

By framing her attachment to Shūichi as fate and reincarnation, she can approach him without having to name the humiliating details of childhood neglect, her mother’s complicated position, and her own years of searching. The story gives her a role with dignity—someone brave, someone chosen—rather than someone who waited outside like a forgotten child.

Shūichi’s resistance to the fantasy is also revealing. He isn’t only skeptical; he is frightened by intimacy that arrives too quickly, too confidently, because his life has taught him that closeness can be followed by abandonment.

In that sense, the “lie” becomes a test of whether someone will stay when the performance drops. The same pattern appears in Hiro’s sections, though his disguise is quieter: he hides his identity from Ayako, hides his illness, and even hides from his own memories by turning his regrets into a private monologue rather than a conversation.

The book does not treat deception as a simple moral failure. It treats it as a survival habit that forms when a person expects rejection.

What changes the characters is not punishment for lying; it is the moment when someone insists on sharing the burden of reality. Shūichi’s anger after Chinatsu’s confession isn’t really about the false story; it is about her deciding alone, leaving alone, and denying him the chance to choose her with full knowledge.

The narrative keeps returning to a central idea: truth is difficult not because it is complicated, but because it makes a person visible, and visibility creates risk. Love, in this world, begins where the fear of being known is met with steady presence rather than ridicule.

Abandonment, responsibility, and the work of repair

Many relationships in the book are shaped by someone leaving and someone being left behind, and the story examines how abandonment changes a person’s sense of agency. Shūichi’s father drags cruelty into everyday life, teaching Shūichi to expect humiliation and to cope by shrinking his needs.

That early training carries into adulthood: after Megumi leaves, Shūichi settles into a belief that return is impossible, that hoping is naïve, and that waiting is safer than acting. Chinatsu’s childhood experience mirrors his—two children left outside while adults choose their own desires—and this shared origin is important because it shows how abandonment creates a quiet kinship among survivors.

Later, Hiro’s choice to walk away from Sanae becomes a long-term study of self-justification. He convinces himself that leaving is kindness, that money can replace presence, that ambition excuses damage.

The book makes the consequences unavoidable: his later life is not “punished” by fate in a simplistic way, but his avoidance becomes a habit that spreads into every area—marriage, work, drinking, health. What finally disrupts these cycles is a shift from passive regret to active responsibility.

Shūichi goes to the factory rather than waiting for Sunday. He says directly what hurt him: not the confession itself, but the unilateral decision to disappear.

Hiro quits drinking and chooses surgery because he decides his future actions still matter, even if the past cannot be repaired. The book’s view of responsibility is practical: apologizing is necessary, but it is not the finish line.

Repair is shown as effort over time—showing up, speaking plainly, asking rather than assuming, allowing other people to respond with their own feelings. Even Shūichi’s decision to someday face his father suggests a movement away from being acted upon and toward choosing his own stance.

The theme insists that abandonment may explain someone’s patterns, but it does not have to define their next decision.

Grief, continuing bonds, and learning to live beside absence

Loss in the book does not fade into the background; it remains present in daily routines, anniversaries, objects, and the way characters misread their own feelings. Shizuku’s relationship with her sister Sumiré is especially central to this.

Sumiré’s death shapes Shizuku’s sense of herself, not only through sadness but through a pressure to make meaning out of what remains. The memorial gathering brings out the social side of grief—relatives who judge, rituals that feel heavy, a mother who is physically distant because her life is elsewhere.

Shizuku carries her sister in sensory details: the stars Sumiré named, the summer air, the way a familiar neighborhood can feel haunted by what used to be. Importantly, the book shows how grief can disguise itself as desire.

Shizuku believes she loves Ogino, but the more honest reading is that she longs for a doorway back into the world where Sumiré was alive, and Ogino seems like a living archive of that world. Her attempt to wear Sumiré’s clothes is not simply imitation; it is an experiment in becoming closer to the lost person by borrowing her shape.

The rejection Shizuku receives is painful, but it gives her a cleaner truth: she can miss her sister without trying to replace her or compete with her memory. Hiro’s grief is more delayed but equally intense.

Sanae becomes the fixed point around which his regret circles, and when he learns she has died, grief turns into a moral wake-up: he cannot apologize to her, so he tries to live differently in the time he has left. Ayako’s presence makes grief complicated because she is both separate and connected—her own person, yet carrying small echoes of her mother.

The book suggests that “moving on” is not erasing bonds; it is allowing bonds to change form. People keep the dead with them through habits, phrases, photos, and promises, and the healthiest moments are when those bonds encourage life rather than freeze it.

Redemption through ordinary kindness and second chances

Rather than treating transformation as a single dramatic turning point, the book builds redemption out of modest acts that are repeated until they become a new identity. Chinatsu bringing sweets, Shūichi making coffee with care, Tachibana offering free coffee to a stranger, Ayako giving a drawing for luck—these gestures are small enough to seem harmless, which is why they work.

They do not demand immediate intimacy, and they allow trust to form without pressure. The characters who are most damaged are not repaired by lectures or grand declarations; they are repaired by being treated as worth time and attention.

Hiro’s recovery from alcoholism is described through decision and routine: quitting drinking, accepting help, rebuilding life piece by piece. Shūichi’s growth is shown through learning to act instead of retreating, and through admitting that his anger is connected to his own past behavior.

Even Chinatsu’s growth involves accepting that she cannot control outcomes by disappearing; she must stay long enough to let someone respond. The idea of “second chances” is not sentimental here.

Some chances are missed permanently—Sanae is gone, childhood cannot be re-entered, the years lost to cruelty do not return. Yet the book argues that meaningful change is still available in the present: a person can choose courage today even if they lacked it before.

This is why the repeated phrase “Let’s keep going with zero accidents” matters. It is not a magic spell or a joke; it becomes a shared practice of careful forward motion, a way to say “we will try again, we will be attentive, we will not abandon each other casually.” The café, again, supports this theme because it makes return possible.

You can come back next Sunday. You can sit down again.

You can admit what you did and still be offered warmth. Redemption is framed as a relationship between effort and forgiveness, where both sides participate: one person changes behavior, the other allows space for that change to count.

Coming of age, authenticity, and the courage to choose one’s own shape

Shizuku’s story presents adolescence as a struggle between borrowed identities and self-made identity. She grows up in a café named into her life by her father’s wish, yet she cannot even drink coffee because of an early experience that attached fear to bitterness.

That aversion becomes symbolic: she dislikes the taste, but she also fears what bitterness represents—loss, adulthood, complexity, the possibility that comfort can vanish. As she watches Chinatsu and Shūichi, she sees a gentler love that contrasts with her own confusion, and she begins testing the boundaries of who she might become.

Ogino’s reappearance triggers a powerful mix of nostalgia, admiration, and longing, and she mistakes that intensity for romantic love. The choice to wear Sumiré’s clothes shows how a teenager may reach for an existing template when her own identity feels unfinished.

She tries on her sister’s elegance because it seems like a shortcut to maturity and attention, but the result is discomfort and conflict. Kōta’s anger, and Ayako’s blunt advice at the festival, function as a mirror: both recognize that Shizuku is forcing herself into a shape that is not hers.

The turning point arrives when she chooses to meet Ogino in her own simple clothes and speaks honestly. Even though she is rejected, she experiences a new kind of strength—she can survive embarrassment, survive disappointment, and still keep her dignity.

The real growth is her ability to name what was true: she was longing for her sister, not actually in love with Ogino. That clarity allows her to reconnect with Kōta and to accept care without turning it into a battle.

The decision to try coffee again at the end is not about liking coffee; it is about facing bitterness without letting it control her. It signals readiness for adult life as something she can enter without pretending to be someone else.

By grounding coming-of-age in concrete relationships, everyday jealousy, and sincere apologies, the book treats maturity as the ability to remain oneself under pressure—no costume, no borrowed shadow, just a person choosing her own way forward.