A Day in the Life of Abed Salama Summary and Analysis

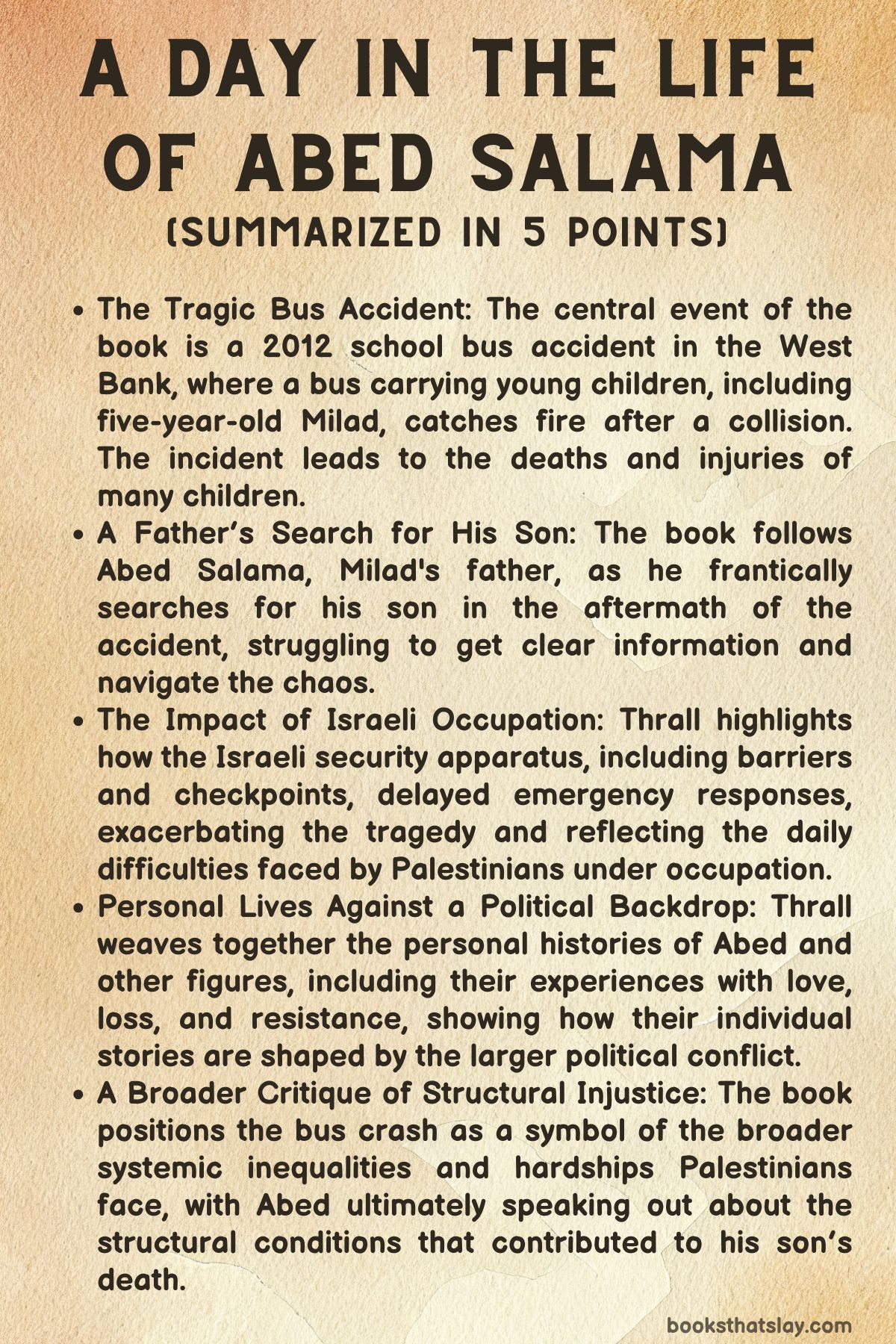

“A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy” is a 2023 nonfiction book by Nathan Thrall, a journalist with deep ties to Jerusalem. The book provides a heartbreaking account of a Palestinian father’s frantic search for his son following a tragic school bus accident.

However, it also goes beyond personal grief to expose the deep structural inequalities Palestinians face under Israeli occupation. Released amid heightened tensions following the 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, the book offers timely reflection on the human toll of decades-long conflict, shedding light on the overlooked struggles of Palestinian life.

Summary

The heart of A Day in the Life of Abed Salama revolves around a devastating bus crash in 2012 that claimed the lives of several young children. Although Nathan Thrall avoids specifying the date in the narrative, the book begins with the chaotic aftermath of the accident.

Abed Salama, a Palestinian father, learns that the bus carrying his five-year-old son Milad has been involved in a fiery collision. Milad had almost stayed home that day, and now, Abed finds himself in a desperate race against time, trying to figure out where his son is and what has happened to him.

From here, Thrall delves into Abed’s life, tracing his past to provide a broader understanding of his emotional journey. Abed’s early years are marked by love and loss, particularly his affection for a young woman named Ghazl, whom he hoped to marry. His resistance to Israeli occupation lands him in prison, which causes tensions in his family and derails his relationship with Ghazl.

In the years that follow, Abed experiences a string of failed marriages, eventually settling down with a woman named Haifa, with whom he has two sons, including Milad.

The story of Abed’s personal struggles intertwines with the larger political and social backdrop of life in the West Bank, where residents live under constant surveillance and restriction.

Other figures are introduced to broaden the perspective of the tragedy. Huda Dahbour, a doctor living nearby, steps in to help as the chaos unfolds, offering medical care to the children caught in the inferno. Radwan Tawam, the bus driver, finds himself at the center of scrutiny after the accident.

Meanwhile, Dany Tirza, the Israeli architect of the West Bank security barrier, plays an indirect role in the incident by complicating access to the accident scene due to the physical barriers and checkpoints that hinder swift emergency response.

Thrall also focuses on Nansy Qawasme and Haya al-Hindi, two mothers whose children were on the same bus as Milad. Both women endure the same excruciating uncertainty as Abed, frantically seeking information about their children’s fate. As the hours pass, the narrative reveals the grim reality: all three families are about to face unbearable loss.

Abed’s son Milad and Haya’s child perish at the scene, while Nansy’s son holds on for a few more hours before succumbing to his injuries.

The core of the tragedy is not just the accident but the excruciating delays in emergency response, exacerbated by Israel’s security infrastructure. Thrall illustrates how the system designed for “security” impedes the very services that could have saved lives.

For Abed, the deaths are not just personal but emblematic of a larger systemic failure, one that stems from decades of occupation and oppression.

In the end, Abed resolves to break his silence, to speak out against the structural violence that he believes took his son’s life, joining the ranks of those who struggle to make sense of loss under occupation.

Characters

Abed Salama

Abed Salama is the central figure in Nathan Thrall’s narrative, a father caught in the excruciating uncertainty of finding his son after the tragic school bus accident. His story is deeply personal but also reflective of the broader Palestinian experience under Israeli occupation.

Thrall weaves together Abed’s journey through life, which includes his youthful idealism, his participation in the Palestinian resistance, and his disillusionment with both personal relationships and the political situation around him. Abed’s early involvement in the resistance leads to a prison sentence, a significant moment that shapes his future decisions.

His failed relationship with his first love, Ghazl, and his subsequent unhappy marriages reveal a man grappling with disappointment and instability in both personal and political realms. His eventual settling down with Haifa and their two sons provides a brief semblance of peace, but the tragic accident and the death of his son, Milad, shatter that fragile balance.

In the aftermath, Abed becomes emblematic of the grief, frustration, and helplessness experienced by Palestinians. His decision to speak out about the loss of his son and the oppressive systems he holds responsible encapsulates his transformation from a man absorbed in personal struggles to one who seeks justice for the structural conditions he believes led to his son’s death.

Milad Salama

Although Milad is only briefly alive in the narrative, his presence looms large over the entire book. Milad’s death in the bus accident serves as the emotional and narrative catalyst for Abed’s story.

His near absence from the amusement park trip initially—he almost didn’t attend—adds an agonizing layer to his father’s subsequent grief. Milad symbolizes the innocence and vulnerability of Palestinian children, caught in the broader geopolitical conflict that surrounds them.

His death is the personal tragedy that intersects with the structural violence of occupation, transforming the story from an individual’s loss into a collective tragedy.

Ghazl

Ghazl represents the missed opportunities and shattered hopes in Abed’s personal life. Abed’s first love, she embodies his youthful aspirations and dreams of personal happiness.

However, their relationship ultimately collapses amid family disagreements, reflecting the broader theme of fragmented Palestinian unity. Ghazl’s role underscores how the pressures of living under constant political tension can seep into personal relationships, tearing them apart.

The failed relationship with Ghazl sets Abed on a path of unhappiness, as his subsequent marriages fail to bring him the solace or stability he seeks.

Haifa

Haifa is Abed’s second wife, with whom he has two sons, including Milad. Though her role is not as central as Abed’s, she represents the quiet endurance of Palestinian women living through personal and political turmoil.

Haifa’s presence offers a fleeting sense of stability after Abed’s earlier failed relationships. Her significance deepens after Milad’s death, as she bears the weight of this unimaginable loss alongside Abed.

Radwan Tawam

Radwan Tawam, the driver of the ill-fated bus, is a figure shrouded in the complexity of guilt, responsibility, and fate. His role in the tragedy is ambiguous—he is not portrayed as the primary cause of the accident, yet he cannot escape his involvement.

Tawam becomes a tragic figure caught in the machinery of a society where even the most basic services, like safe transportation for children, are compromised by larger systemic issues. The difficulty in assigning clear blame highlights the convoluted nature of accountability in a system where many factors, including the failure of emergency services, intertwine.

Huda Dahbour

Huda Dahbour, a local doctor, represents Palestinian professionals who work tirelessly within a flawed and restrictive system. Her role in providing emergency care at the accident scene exemplifies the resilience of those trying to help their communities despite overwhelming obstacles.

Dahbour is a symbol of everyday heroism in Palestinian society, as she works to save lives despite limited resources and access. Her presence underscores the tension between individual acts of compassion and a larger system that fails to effectively support such efforts.

Dany Tirza

Dany Tirza serves as the Israeli official responsible for constructing the security barrier around the West Bank. His role highlights the bureaucratic and structural aspects of the Israeli occupation.

Tirza represents the cold, calculated nature of a system designed to control and contain Palestinian life. The wall he helped build contributes to the tragedy by delaying emergency services during the bus accident, underscoring the devastating consequences of occupation policies justified on security grounds.

Nansy Qawasme

Nansy Qawasme is a mother whose child also dies in the bus accident. Her story parallels Abed’s, adding another layer of parental grief and frustration.

Nansy’s role emphasizes that Abed’s experience is part of a larger pattern of suffering among Palestinian families. Like Abed, Nansy faces the bureaucratic challenges of finding her child after the crash, and her grief reflects the collective suffering of Palestinians enduring systemic failures.

Haya al-Hindi

Haya al-Hindi, another parent who loses a child in the accident, completes the trio of grieving parents. Her story illustrates the shared trauma experienced by Palestinian families, particularly mothers, who must grapple with the emotional toll of their children’s deaths.

Like Nansy and Abed, Haya struggles with the overwhelming pain of loss. Her involvement in the narrative shows how individual stories of loss intersect with the broader societal and political dynamics that shape Palestinian life under occupation.

Analysis and Themes

The Intersecting Forces of Personal and Political Trauma within the Context of Occupation

Nathan Thrall’s A Day in the Life of Abed Salama presents a deeply intricate exploration of personal trauma that cannot be disentangled from the larger political framework of life under Israeli occupation. Abed Salama’s desperate search for his son following the school bus crash is not merely a father’s reaction to an unimaginable personal tragedy, but also a powerful indictment of the systemic barriers that Palestinian families must navigate daily.

The delay in emergency response, exacerbated by the Israeli security forces and the labyrinthine bureaucracy that comes with the occupation, serves as an emblem of how structural violence exacerbates personal grief. The occupation becomes not just a backdrop but an active player in the tragedy.

Abed’s personal history, from his involvement in the Palestinian movement to his broken relationships and eventual family life, highlights how political oppression infiltrates and shapes the most intimate aspects of human life. His failed engagement to Ghazl is laden with intergenerational trauma and communal expectations, all complicated by the political reality of resistance and imprisonment.

Abed’s experiences, and those of other characters, illustrate how Palestinian lives are not only disrupted by overt violence but also by the constant, low-level hum of occupation. Thrall masterfully intertwines personal grief with the broader framework of political repression, presenting a narrative that demands readers see individual pain as inextricably linked with collective oppression.

The Impact of Bureaucratic and Physical Barriers on the Right to Life and Mobility

The school bus crash provides a tragic lens through which to understand how physical and bureaucratic barriers, both literal and metaphorical, impact Palestinian lives. Thrall’s recounting of the accident centers not only on the collision itself but on the deeply flawed response to the emergency, where the separation wall and other security apparatuses play a lethal role.

The inability of emergency services to arrive in time, compounded by the intricate system of checkpoints, walls, and restricted roads, turns what should be a moment of urgent care into a deadly delay. This failure is emblematic of the broader, everyday violence of the occupation, where mobility—the right to move freely, to access services, and to respond to crises—is a privilege denied to Palestinians.

The structural violence at play here isn’t simply the wall or checkpoints as physical objects but as manifestations of a system that systematically undermines the right to life. The very infrastructure designed to protect Israeli citizens from violence, in the form of the separation barrier, becomes a key contributor to the deaths of Palestinian children.

Thrall carefully unpacks this theme, showing how these barriers, justified under the banner of security, often produce suffering and death for those on the other side. The narrative calls into question the ethics of a security apparatus that not only divides land but fractures the very possibility of coexistence.

The Tragic Consequences of a Fractured Social Fabric under Prolonged Occupation

The book not only focuses on the physical and political barriers but also the psychological and social fragmentation that results from prolonged conflict and occupation. Abed’s personal story is one of repeated fracture: his romantic relationship with Ghazl collapses due to family infighting, and his later marriages are marked by unhappiness and instability.

These personal ruptures mirror the broader disintegration of Palestinian social structures under occupation. Thrall subtly suggests that the occupation doesn’t just exert pressure on individual bodies or political systems, but also on the fundamental social bonds that hold communities together.

The characters in the book, from Abed to Huda Dahbour, Nansy Qawasme, and others, reflect a society that is frayed by decades of instability. Personal and familial relationships are caught in the crosshairs of political conflict. The tragedy of the bus accident exposes the limits of communal support in the face of overwhelming structural challenges.

As families scramble to locate their children and navigate a broken system, their grief becomes a collective yet isolating experience. Thrall emphasizes that prolonged occupation creates not only physical and political barriers but erodes the very foundation of community and social cohesion.

The Role of Memory, Commemoration, and the Struggle for Narrative Sovereignty in the Context of Occupation

The book also grapples with the theme of memory and how the act of remembering itself becomes a contested space in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Thrall’s decision to leave out the date of the accident underscores how Palestinian tragedies, while profound, are often rendered timeless in the larger narrative of occupation.

The deaths of these children are part of an unending cycle of violence, displacement, and suffering that stretches back decades. By omitting the date, Thrall situates the accident as part of a broader collective memory of Palestinian suffering that defies chronological boundaries.

The book highlights the struggle for narrative sovereignty. Abed’s decision to speak out after his son’s death is an attempt to reclaim agency over the story of his loss. In a political landscape where Palestinians often feel their stories are erased, minimized, or misrepresented, the act of telling one’s story becomes an act of resistance.

Thrall’s narrative foregrounds Palestinian voices and experiences, participating in this struggle. The theme of memory in the book is not just about remembering a specific tragedy but about the larger battle over how these tragedies are understood and commemorated.

The Intersection of Infrastructural Violence and Environmental Determinism in a Militarized Landscape

Lastly, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama examines how the physical environment itself—both natural and constructed—plays a determinative role in the fates of those living under occupation. The crash and the resulting fire are shaped by infrastructural deficiencies that plague the occupied territories.

The landscape of the West Bank, with its dangerous roads, militarized zones, and settlements, becomes a death trap for the most vulnerable, in this case, young children. The environment here is not neutral but deeply political.

The separation wall, checkpoints, and restricted areas are designed to shape behavior, movement, and ultimately, life and death. Thrall presents an analysis of environmental determinism under occupation, where geography and infrastructure become tools of control and violence.

This theme asks readers to consider how the land itself, far from being a mere setting for conflict, is an active agent in the suffering of its inhabitants. Thrall offers a profound reflection on how the militarized landscape of Palestine shapes the possibilities for life, with infrastructural violence becoming a key mechanism of control.