A Ferry Merry Christmas Summary, Characters and Themes

A Ferry Merry Christmas by Debbie Macomber is a warm, holiday-time contemporary romance set almost entirely on a Washington State ferry. Two days before Christmas, a routine crossing from Bremerton to Seattle turns into an hours-long breakdown in Puget Sound.

The delay strands strangers together and quietly rearranges their lives. Through shifting viewpoints, the story follows an accountant still mourning her grandmother, a Navy sailor on leave, a little girl wishing for her parents to reunite, a woman carrying gingerbread cookies toward reconciliation with her twin, and an anxious husband racing to reach his laboring wife. The ferry becomes a small, temporary community where kindness spreads.

Summary

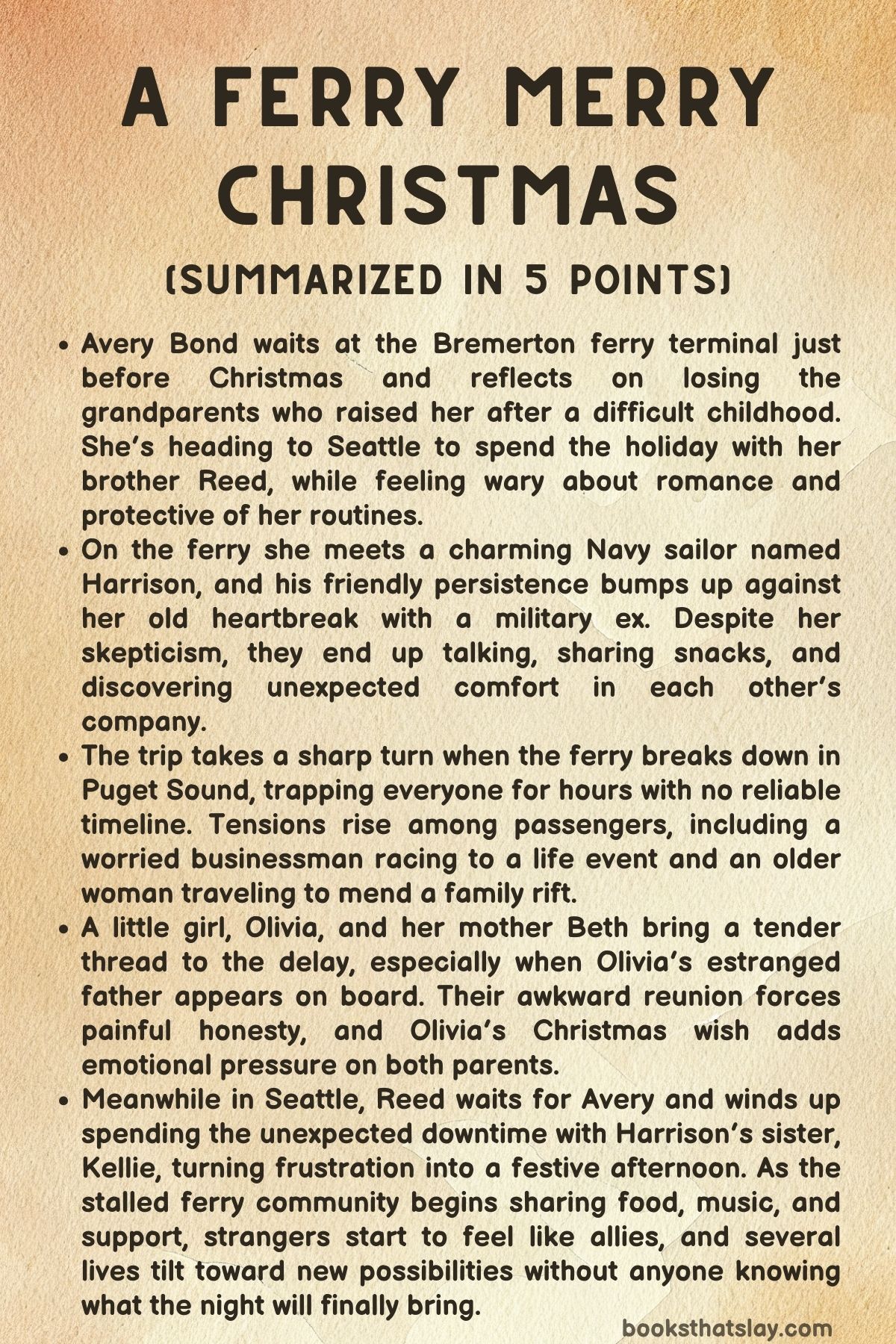

Avery Bond sits in the Bremerton ferry terminal two days before Christmas, killing time by watching other travelers. One man stands out as frantic and rushed, and an older woman carries a tin of holiday treats that stirs Avery’s memories of her grandmother.

Avery’s thoughts drift to her own past. She and her brother Reed were raised by their grandparents after their mother’s addiction made her unable to care for them.

Their mother died young, their father never stepped up, and the grandparents became their safe harbor. Avery’s grandfather died when she was fifteen, and her grandmother—Grams—passed away recently after cancer.

Avery and Reed sold the family home, bought condos, and planned a quiet Christmas together in Seattle, their first without Grams. Reed has built a high-powered career at Microsoft, and Avery is proud of him, even if she suspects he is always trying to manage her life.

What annoys her most is his ongoing habit of setting her up with friends. Avery likes steadiness and keeps her walls up when it comes to dating, especially after a college romance with a sailor named Rick ended in humiliation when she learned he was married.

Boarding begins, and Avery joins the walk-on line. A Navy sailor about her age runs in late and falls in behind her.

She notices his easy charm and good looks but tightens inside as soon as she sees the uniform. He tries friendly conversation, explaining that he has been at sea twelve weeks and is headed to Seattle to see his sister.

He asks if Avery is meeting a man. Wanting to shut down any flirtation, she says yes—meaning Reed—but lets it sound as if she has a boyfriend waiting.

On board, she takes a seat alone. The sailor is greeted by friends across the deck, and she hears his first name as “Harry.”

A cheerful little girl named Olivia plops down beside Avery and immediately starts talking about visiting Santa in Seattle and wanting an iPad. Her mother, Beth Sullivan, sits after her, apologizing for Olivia’s bold friendliness.

Olivia soon shares a different wish in a whisper meant only for Avery: she wants her daddy to come home. Beth’s face gives away a buried ache.

Avery, still thinking about Grams and the emptiness of this coming holiday, listens with quiet sympathy.

Reed calls Avery to say he is already waiting at the Seattle terminal. He insists on meeting her at the dock and taking her to lunch at Anthony’s.

Avery correctly guesses this might be another matchmaking attempt. She makes him promise lunch will be just the two of them.

Across the ferry deck, the sailor—Harrison Stetler—watches Avery and tells his shipmates Dan and Kyle that he’d like to get to know her. Harrison is on leave after a long stretch underwater, and he is excited to see his sister Kellie, a Microsoft executive he hasn’t visited in two years.

Noticing the engine noises, Kyle reports a mechanical concern to a crewman, but is brushed off. Soon the ferry slows, then stops fully in Puget Sound.

The captain announces an engine failure and says a replacement part is needed, without offering a clear timeline. Frustration spreads through the passenger areas.

One of those passengers is Virginia Talbot, a middle-aged woman carrying a tin of homemade gingerbread cookies. She is on her way to see her twin sister Veronica for Christmas, hoping to repair a two-year rift sparked by a bitter argument over their late mother’s china.

Their recent texts have been sharp and tentative. Veronica has warned her not to arrive late, so the breakdown feels like a cruel test to Virginia.

She fears the fragile opening between them will close again.

Avery texts Reed about the delay. Drifted from her private seat by hunger and restlessness, she ends up in the cafeteria line where she runs into Harrison again.

In conversation she lets slip that the man waiting in Seattle is her brother. Harrison introduces himself properly and gently challenges her rule against dating sailors.

He asks only for conversation until they reach shore. She says yes, half to pass time and half because she can’t deny her curiosity.

Food sells out fast; they wind up with popcorn and Skittles, which they share while sitting together. Virginia, overhearing their talk, warns Avery to be careful with Navy men.

Avery and Harrison start to enjoy each other. She explains she is an accountant who likes routine and order.

He talks about ten years in the Navy, his work in submarine missile defense, and how enlistment helped him trade a reckless youth for discipline. Avery feels herself relaxing, even though she assumes nothing lasting could work with someone who lives at sea.

As the delay deepens, Avery sees the anxious businessman she noticed earlier. His name is James, and his pregnant wife Lilly has gone into early labor in Seattle, alone.

Harrison recruits Dan, a medic, to reassure James that first labors tend to take time and to advise him to get support to Lilly while he’s stuck offshore.

Olivia’s family story becomes clearer. Beth and Logan Sullivan separated two years earlier.

Medical bills from Olivia’s premature birth, financial pressure, and Logan’s pride pulled them apart. Logan has been asking for divorce, while Beth has kept a quiet hope that they might find a path back.

In a jolt of coincidence, Olivia spots Logan on the ferry. She runs to him, thrilled, and his surprise turns into tenderness.

Beth is forced into a wary conversation with him. Olivia begs Logan to come to Christmas dinner at Beth’s parents’ home.

Logan admits he was laid off and is riding the ferry to sell his motorcycle for money. The child’s hope and Beth’s honesty soften him, and he agrees to try, if her parents will have him.

Beth makes the call, taking a first step toward mending what broke.

In Seattle, Kellie waits for Harrison at the terminal and meets Reed Bond, who recognizes her from a Microsoft workshop. Both are there for delayed siblings.

Since Avery won’t make lunch, Reed offers Kellie his reservation at Anthony’s. Over lunch they trade backstories.

Kellie has recently ended a relationship with a coworker who used her and misled her about commitment, leaving her guarded. Reed shares how Avery sacrificed much of her young adult life to care for their grandmother.

They discover mutual attraction while the news confirms the ferry will be delayed for hours. With nothing else to do, Reed and Kellie turn waiting into a holiday afternoon—Pike Place Market, the original Starbucks line, and the Seattle Great Wheel.

Their easy companionship grows into something promising.

Back on the ferry, tension peaks. An empty ferry passes them without towing or rescuing, and passengers snap at the crew.

Earl Jones, a crewman, tries to calm everyone but is overwhelmed. Virginia, hurt by another curt message from Veronica, decides that stewing in anger helps no one.

She opens her tin and offers gingerbread cookies, letting Olivia hand them out. The gesture changes the temperature of the crowd.

Other passengers share what food they have, musicians pull out instruments, and irritation gives way to a makeshift holiday gathering. Virginia and Veronica’s text exchange cools as truth replaces blame; Veronica admits she still wants Virginia to come, and Virginia promises she will, ferry or no ferry.

Mechanical updates arrive in fits and starts. A replacement part is located and ferried out, but the fix fails; a tugboat is needed.

James grows frantic as Lilly’s labor advances. Avery lends her phone when his battery dies, and passengers rally around him with chargers, reassurance, and practical support.

A nurse onboard, Cherise, takes charge, coaching Lilly over speakerphone. The crowd times contractions aloud so Lilly can hear steady voices.

At her request, the musicians play country songs and Christmas tunes through a Bluetooth speaker. The ferry, once angry, becomes a chorus of strangers helping a woman they’ve never met bring a baby into the world.

In the middle of that shared focus, Beth and Logan finally talk without armor. Logan admits shame over accepting financial help from Beth’s parents and how broken he felt as a provider.

Beth admits her secrecy made things worse. Remembering Olivia’s birth and the fear they survived together cracks open the distance between them.

Beth tells Logan she wants him back. He admits he regrets leaving and agrees to come home.

Then the miracle of the day arrives through a phone speaker: Lilly delivers a baby girl. The doctor’s announcement is followed by the newborn’s cry.

James sobs, laughs, and tells everyone her name—Noelle Rose. Cheers erupt across the deck.

In the swell of joy, Avery lets herself imagine a future that isn’t shaped by past betrayal. She agrees to see Harrison again after Christmas, and they share a kiss that feels like a beginning.

With the tugboat’s help, the ferry finally reaches Seattle. Passengers disembark calmer than they boarded, bonded by the long wait and what they gave one another.

James rushes to the hospital on Logan’s motorcycle. Virginia reaches Veronica’s home, where the twins embrace and apologize, choosing family over old arguments.

Christmas Day brings follow-through. Beth’s parents welcome Logan, and Beth’s father privately admits his mistake in paying bills without including Logan.

He tells Logan Beth chose him for his character and urges him to rebuild their family. A year later, the ferry group reunites at Noelle’s first birthday.

Avery and Harrison are steadily together, Beth and Logan are thriving and expecting another child, and Reed and Kellie are engaged. Hearing that another ferry has stalled on the same route, they recognize how one long delay turned a stressful day into the start of new lives.

Characters

Avery Bond

Avery is the emotional anchor of A Ferry Merry Christmas, carrying a quiet resilience shaped by early loss and instability. Raised by her grandparents after her mother’s addiction and her father’s unfitness, she grew up learning to be self-reliant and cautious, especially in matters of love.

Her grief is fresh—first her grandfather, then her grandmother “Grams,” whom she cared for until cancer took her—so this Christmas is not just a holiday but a test of how to live without the people who defined safety for her. Avery’s personality reflects her coping style: she is practical, routine-oriented, and guarded, choosing the predictability of accounting because it mirrors the order she had to build for herself.

Her suspicion of romance is not cynicism for its own sake; it is a protective reflex born from betrayal, particularly her college relationship with Rick. Yet the ferry delay forces her into community and intimacy, and she slowly reveals her tenderness—first through empathy for strangers like James, then through her growing ease with Harrison.

By the end, Avery’s arc is not about suddenly becoming carefree, but about permitting hope again while still honoring who she has had to be to survive.

Harrison Stetler

Harrison is introduced through Avery’s wary gaze—handsome, a Navy man, and therefore a walking trigger for her past—but his deeper role in A Ferry Merry Christmas is to challenge fixed narratives about people and second chances. He is disciplined without being stiff, friendly without pushing, and confident enough to flirt playfully while respecting Avery’s boundaries.

His background adds dimension: he joined the Navy not as an inevitable calling but as a deliberate choice to reinvent himself after a rebellious youth, implying a man who understands personal change from the inside. Harrison’s patience during the crisis shows his values more clearly than his charm: he brings coffee to James, helps keep Lilly connected by finding a charger, and supports the collective effort to steady her labor through song and counting.

He doesn’t need to dominate the moment; he contributes quietly and consistently, which is precisely what makes him credible to Avery. Harrison also represents a balanced kind of masculinity—he’s emotionally available, comfortable with community, and unashamed of wanting connection.

His romance with Avery is built not on grand gestures but on earned trust in ordinary conversation under extraordinary circumstances.

Reed Bond

Reed embodies the protective older-brother role, but A Ferry Merry Christmas gives him more nuance than a simple caretaker archetype. He is successful at Microsoft and clearly loves Avery, yet his affection comes out as control—especially in his persistent matchmaking.

That behavior isn’t rooted in arrogance so much as worry. Reed saw Avery sacrifice her youth to care for Grams and wants to “fix” what he thinks she missed, but he underestimates how much her independence matters to her.

The ferry delay becomes a subtle turning point for him: instead of orchestrating Avery’s life, he is sidetracked into his own unexpected connection with Kellie. Through lunch and their shared wandering around Seattle, Reed shifts from being a planner for others to someone willing to be surprised himself.

He reveals emotional honesty when he explains their childhood to Kellie, showing that his steadiness has been forged in the same fire as Avery’s, just expressed differently. Reed’s trajectory suggests quiet growth—learning that love doesn’t need to be managed to be real.

Kellie Stetler

Kellie functions as a mirror to Avery in A Ferry Merry Christmas, offering another portrait of a competent woman whose heart has been bruised by disappointment. She is a Microsoft executive who appears polished and capable, yet her avoidance of talking about herself quickly signals guardedness.

Her past relationship with Jude left her wary of being valued only for professional advantage, so she approaches romance cautiously, especially with coworkers. What makes Kellie compelling is the warmth beneath that caution.

She doesn’t mock sentiment or resist connection outright; she simply needs proof that it’s safe. Her day with Reed—lunch, Pike Place, the Great Wheel—softens her through shared joy rather than forced vulnerability.

She is playful enough to agree to knit a hat on impulse, a small act that symbolizes her willingness to invest in someone again. Kellie’s role is also familial: she is eagerly waiting for Harrison, highlighting her loyalty and affection as a sister.

Her engagement to Reed a year later feels earned because it grows from mutual respect and gradual trust, not sudden holiday magic alone.

Olivia Sullivan

Olivia is the story’s spark plug—small, direct, and emotionally fearless in A Ferry Merry Christmas. She radiates childlike excitement about Santa and iPads, but her real desire is deeper and heartbreakingly simple: she wants her father home.

Olivia’s openness cuts through the adult world’s cautiousness; she says what everyone else is too afraid to articulate. Her innocence is also a quiet form of wisdom: she doesn’t deny pain, but she refuses to accept separation as permanent when love still exists.

Olivia catalyzes reconciliation by physically running to Logan on the ferry and emotionally refusing to let him retreat behind shame. Even her playful moments—asking if Harrison is Avery’s boyfriend or encouraging reindeer drawings—are tools of connection.

She represents hope not as naïveté but as persistence, and the adults around her change partly because they cannot bear to disappoint someone so unguardedly loving. Olivia is the child through whom the book argues that families can be rebuilt if people are brave enough to try.

Beth Sullivan

Beth carries the quiet ache of abandonment in A Ferry Merry Christmas, not only from Logan’s departure but from the slow erosion of trust that preceded it. She is portrayed as exhausted but not bitter, still hoping for reconciliation even after two years of practical and emotional strain.

Beth’s struggle is layered: she is balancing motherhood, the humiliation of being left, financial stress, and the fear that wanting Logan back might be a form of weakness. Yet her strength shows in her honesty.

When the ferry crisis forces an encounter, she chooses conversation instead of avoidance, and later she admits her own role in the rift—especially the secrecy over her parents paying medical bills. Beth’s love is not blind; it is deliberate.

She wants a partner, not a rescuer, and her willingness to ask for what she needs becomes the moral pivot of her arc. By the time Logan returns, Beth hasn’t “won him back” through pleading; she has rebuilt the bridge through clarity, vulnerability, and self-respect.

Logan Sullivan

Logan is one of the most psychologically complex figures in A Ferry Merry Christmas, defined by shame more than malice. He left Beth not because he stopped loving his family but because he felt crushed by inadequacy after Olivia’s medical crisis and the financial fallout.

The revelation that Beth’s parents quietly covered bills shattered his sense of being a provider, and his pride turned into self-exile. Logan’s internal world is shaped by old wounds—childhood abandonment and a cruel father—so failure feels not temporary but identity-level.

His plan to sell his motorcycle shows both desperation and devotion; he is trying, in his way, to show up for Olivia, even if he can’t yet show up emotionally for Beth. The ferry ordeal dismantles his defenses: Olivia’s trust, Beth’s honesty, and communal kindness during Lilly’s labor force him to see that love is not something you earn only by being flawless.

His return is believable because it comes after self-recognition and apology, not because circumstances magically improve.

Virginia Talbot

Virginia represents the theme of reconciliation outside romance in A Ferry Merry Christmas. She is practical, proud, and deeply wounded by the fight with her twin sister Veronica over their mother’s china—an argument that is really about grief, identity, and feeling unseen.

Bringing gingerbread cookies is both a peace offering and a symbol of who she is: a woman who expresses love through doing, cooking, arriving even when it’s hard. The ferry delay threatens her fragile attempt at mending things, and her anxiety reveals how much she wants connection despite her brusque exterior.

Her decision to share the cookies when tempers flare shows emotional intelligence; she intuitively understands that community can soften isolation. Virginia’s arc is small but meaningful: she learns that reconciliation isn’t ruined by imperfect timing, and that love can survive pride if someone risks the first step.

Veronica Talbot

Though mostly offstage, Veronica’s presence in A Ferry Merry Christmas is powerful because she embodies the other half of a broken bond. Her terse texts and initial rigidity suggest someone who has also been wounded and who uses anger to protect herself.

The inherited china fight hints at long-standing rivalry and grief magnified by loss. Yet Veronica’s eventual softening, sending Phoebe to meet Virginia and welcoming her home, shows that her resistance was never indifference.

She wants reconnection but fears being hurt or diminished again. When the twins finally embrace and apologize, Veronica completes the story’s argument that estrangement is often a misunderstanding left to rot, not a lack of love.

James

James begins as a stereotypical frantic businessman in A Ferry Merry Christmas, but the delay strips that surface away to reveal a vulnerable, devoted husband. His urgency comes from love rather than ego; he doesn’t care about meetings or status once he learns Lilly is in labor alone.

James moves from isolated panic to shared experience, letting strangers witness his fear and then his joy. His willingness to accept help—from Dan’s reassurance to Avery’s phone to Cherise’s coaching—marks a subtle humility.

By narrating Lilly’s contractions out loud, he also becomes a conduit for communal empathy, allowing the whole ferry to participate in something life-affirming. His transformation underscores the book’s idea that crisis can re-humanize people who otherwise move through life armored.

Lilly

Lilly is physically absent for most of A Ferry Merry Christmas, yet emotionally central during the labor sequence. Through her voice on the phone, she appears courageous, practical, and receptive to support.

She accepts counting, coaching, and music from strangers without embarrassment, suggesting a person who values connection over pride. Her labor becomes a shared rite for the ferry passengers, turning her private ordeal into a communal celebration.

Naming her daughter Noelle Rose seals Lilly’s role as the quiet heart of the story’s most dramatic event: she brings literal new life into a stalled, tense world.

Dan

Dan, Harrison’s shipmate and a medic, plays a steadying role in A Ferry Merry Christmas. He is the kind of person who responds to anxiety with structure, offering James realistic reassurance about first births and later helping the crowd shift from helplessness to support.

Dan’s presence highlights the non-romantic value of the Navy characters: they are not merely love interests but competent, service-oriented people whose training becomes useful in civilian crisis. His calm professionalism helps set the tone for the ferry’s eventual solidarity.

Kyle

Kyle serves as an early warning voice in A Ferry Merry Christmas, noticing the engine’s wrong sound before the breakdown. Though his role is brief, it reveals a perceptive and slightly skeptical personality—someone who trusts experience more than authority.

His awareness also foreshadows the story’s main ordeal and shows how ordinary expertise can be dismissed until it’s too late, a small reflection on listening and humility.

Earl Jones

Crewman Earl Jones embodies the stress of responsibility in A Ferry Merry Christmas. He is caught between an increasingly hostile crowd and a problem he cannot quickly solve.

His attempt to explain the severe backlog and promise repair shows he is trying to treat passengers as adults, but his retreat under pressure reveals how overwhelming collective anger can be. Earl’s later announcement of the tugboat and docking becomes a moment of relief not just for travelers but for him personally.

He represents the often unseen labor of public service: trying to hold order while being the most immediate target of frustration.

Captain Douglas

Captain Douglas is a figure of institutional duty in A Ferry Merry Christmas, tasked with balancing safety and fairness. His refusal to let James board the delivery boat is harsh emotionally, but consistent with a leader fearing chaos and escalation.

Douglas’s decisions show the limits of compassion within systems: he can empathize, but he must prioritize the whole ship. By the end, his successful coordination of repair and tug assistance restores order, positioning him as a reminder that authority in crisis is rarely about satisfying everyone, but about preventing the worst outcome.

Cherise

Cherise, the nurse passenger, is a quiet hero in A Ferry Merry Christmas. She steps forward without fanfare when she realizes Lilly needs guidance, translating medical knowledge into calm, human language.

Her coaching makes the difference between panic and manageable focus for both Lilly and James. Cherise also models altruism: she doesn’t ask to be in charge, but she accepts responsibility when needed.

Her presence highlights the theme that ordinary people can become extraordinary supports when they choose to show up.

Grant

Grant, Beth’s father, appears late but delivers one of the story’s most important forms of accountability in A Ferry Merry Christmas. He apologizes to Logan for paying bills without consulting him, acknowledging that good intentions can still wound someone’s dignity.

Grant’s conversation with Logan reframes masculinity away from pride and toward perseverance and love. He is firm but compassionate, offering Logan a path back into the family without humiliation.

Grant functions as a moral elder figure, echoing the lost guidance Avery once received from her grandparents.

Phoebe

Phoebe, Virginia’s grandniece, is a small but symbolic character in A Ferry Merry Christmas. She is the physical sign that Veronica is willing to reconcile, sent to meet Virginia at the terminal.

Her role shows how family repair often involves younger generations acting as bridges, whether intentionally or simply by being present. Phoebe represents the future that makes reconciliation worth pursuing.

Rick

Rick exists in Avery’s backstory in A Ferry Merry Christmas, but his impact is outsized. He is the betrayal that hardened Avery’s boundaries, not because he was a sailor, but because he embodied deception and abandonment—two themes already embedded in her childhood.

Rick’s disappearance and secret marriage taught Avery that attraction can be dangerous and trust can be humiliating. He functions less as a character to be understood and more as a scar that explains why Avery needs more than charm to risk love again.

Jude

Jude, Kellie’s former boyfriend, is another offstage catalyst in A Ferry Merry Christmas. His manipulation—performing commitment while using Kellie for career gain—left her guarded around workplace romance.

Jude represents a specific kind of modern betrayal: not dramatic disappearance like Rick’s, but opportunistic exploitation. His presence in her memory allows Kellie’s slow trust in Reed to feel meaningful because it is earned against real skepticism.

Noelle Rose

Noelle Rose, James and Lilly’s newborn, is the literal embodiment of renewal in A Ferry Merry Christmas. Her birth transforms the stalled ferry from a place of irritation into a place of wonder.

She functions less as a developed character and more as a symbol: life arriving right on time within delay, and hope growing out of inconvenience. The one-year reunion centered on her birthday underscores how a single fragile moment can reshape many lives.

Themes

Grief, memory, and carrying love forward

Avery’s wait in the ferry terminal is already soaked in absence. She is two days away from the first Christmas without her grandmother, and that loss is not a background detail; it shapes how she sees everything.

The older woman with homemade treats pulls Avery into a vivid memory of her Grams, and that moment shows how grief works in ordinary life: it arrives through smells, objects, and strangers who accidentally mirror what is gone. Avery’s childhood history deepens this theme.

Being raised by grandparents after parental addiction and instability means her grandparents were not just caregivers but the center of her emotional world. Their deaths remove a whole sense of belonging, and the sale of their house marks a second kind of goodbye, less dramatic but equally final.

The story treats grief as something that does not end neatly. Avery is functional, responsible, even witty, yet her caution about dating and her preference for routine feel like strategies built to prevent more pain.

The ferry breakdown then becomes a strange space where grief is both present and challenged. Avery is pulled into the needs of others—James’s panic, Beth’s family crisis, Olivia’s hope—and that shared urgency gently loosens her isolation.

Instead of grieving alone, she participates in a temporary community that makes room for sorrow and joy at the same time. By the end, grief has not vanished; it has shifted into a quieter companion that allows new bonds.

The one-year-later reunion underlines this movement. The characters do not replace what they lost; they grow around it.

Christmas, in A Ferry Merry Christmas, is not about pretending sadness isn’t there; it is about letting memory stand beside present love, so that what was received in the past becomes something you can still give in the future.

Trust after betrayal and the risk of opening up

Avery’s first instinct toward Harrison is attraction followed by self-protection. Her college relationship with Rick—who disappeared and was secretly married—left a scar that is specifically tied to military men, but the deeper wound is about believing someone’s words and being made to feel foolish for it.

That background explains why Avery says she is meeting “a man” even when she means her brother. She is used to guarding herself, not only from romance but from being read too easily by strangers.

Harrison, on the other hand, enters the ferry wanting connection. He notices her, tries to talk, and accepts her coolness without turning it into a fight.

Their later conversation works because it is deliberately limited: he offers only companionship for the duration of the ride, no promises, no pressure. That small, bounded invitation feels safe enough for Avery to test trust again.

The question game they play is a key step; it is not a grand confession, just a gradual trade of honest answers that lets her feel seen without being cornered. Trust in the book is therefore shown as incremental, made of tiny risks rather than sweeping declarations.

This theme echoes in Kellie’s story. She was misled by Jude, whose ambition outgrew his sincerity, and she now fears dating in her workplace.

Reed respects that boundary while still expressing interest, making trust possible for her too. Even Logan and Beth live inside a trust rupture shaped by shame and silence.

Their reconciliation does not come through a flashy apology, but through admitting fears and naming what went unsaid. The ferry delay forces truth into the open because there is nowhere to escape to.

People either harden or soften; most choose softness. By presenting several versions of betrayal and repair, A Ferry Merry Christmas argues that trust is not restored by denying the past but by meeting it directly, then choosing to act differently anyway.

Love becomes credible when it is patient, specific, and willing to grow at the speed of the wounded person, not at the speed of a holiday deadline.

Community formed through shared crisis

The stalled ferry turns a routine commute into a long, uncertain ordeal, and the story uses that disruption to show how community can appear among strangers. At first, passengers are fragmented by their private urgencies: Avery missing lunch plans, Virginia fearing her reconciliation will fail, James desperate to reach his laboring wife, Beth managing her family pain, and countless unnamed riders simply furious at inconvenience.

The atmosphere begins with complaint, suspicion, and blame. Yet a slow shift happens once people start noticing one another’s vulnerability.

James’s situation becomes the hinge. When the crowd hears his wife is alone in labor, irritation gives way to empathy.

Avery lending her phone is a simple act, but it opens a channel for others to offer chargers, reassurance, and attention. Cherise’s volunteer coaching and the passengers counting contractions together create a chorus of care that makes the deck feel like a single room.

Music then enlarges that unity. The band’s decision to play for Lilly is not entertainment; it is service, a way of holding someone’s fear.

Virginia’s gingerbread cookies work similarly. She shares them almost out of frustration, but the act gives people a reason to look at each other kindly.

Food, counting, singing, even a conga line later on—these are rituals of belonging that form quickly when people face uncertainty together. Importantly, the book does not treat community as perfect.

People yell at crewman Earl, threats of lawsuits fly, and impatience is real. The point is not that humans are automatically generous, but that generosity becomes easier once a shared story replaces separate agendas.

The ferry becomes a temporary village where roles emerge naturally: someone calms, someone feeds, someone instructs, someone jokes, someone listens. In A Ferry Merry Christmas, this kind of spontaneous community is not a sentimental extra; it is the mechanism that changes lives.

The crisis gives individuals an excuse to step outside their usual scripts and practice care without long histories or obligations. When the passengers finally disembark calmly and bonded, the book suggests that belonging is not only something you inherit through family or long friendships.

Sometimes it is built in a single day by people who decide to treat a stranger’s problem as partly their own.

Family rupture and the possibility of repair

Nearly every main character is carrying a broken family tie, and the story places these fractures side by side to show different paths toward healing. Avery’s family rupture is old and structural.

Her parents’ failures forced her grandparents to become parents again, and their deaths raise the fear that she and Reed might drift without that anchor. Reed’s insistence on spending Christmas together is his way of protecting that bond, even if his matchmaking schemes annoy Avery.

Their sibling relationship shows repair through steadiness: they keep choosing each other, not because everything is easy, but because losing their grandparents made them understand what family can mean when it is chosen and maintained. Virginia and Veronica offer another kind of rupture—one born from pride and a seemingly small dispute over inherited china that grew into two years of silence.

Their conflict shows how grief can distort relationships, turning objects into symbols of love or betrayal. The ferry delay threatens their reunion, but it also pushes them into honesty.

Virginia’s refusal to quit, and Veronica’s eventual softening, show repair as a decision to value the relationship more than the argument that froze it. Beth, Logan, and Olivia display the most fragile rupture.

Their separation is steeped in financial stress, shame, and a man’s fear of not measuring up. Olivia’s longing for her father is simple and direct, and her innocence forces the adults to face what their silence is doing to her.

Repair here is not portrayed as instant forgiveness; it is an uncomfortable conversation about hidden help, wounded pride, and regret. Logan’s return home finally comes when he can name his failure without being destroyed by it, and when Beth can admit her own part in the secrecy.

Even James and Lilly belong to this theme in a gentler way. Their crisis on the day of labor exposes how families rely on wider circles; the ferry passengers become a temporary extension of their family, helping birth Noelle into the world.

A Ferry Merry Christmas treats family as both a source of hurt and a place where hope stays stubbornly alive. Repair does not erase what happened, but it re-orients people toward each other with clearer eyes and softer pride.

Time, chance, and the quiet ways life changes

The entire plot hinges on a delay that no one chooses. A ferry engine problem becomes a reminder that time is not fully ours to manage, no matter how carefully we plan.

Avery expects a neat afternoon and a controlled holiday visit; Reed expects lunch with his sister; Kellie expects to pick up her brother; Virginia expects a tense but on-time arrival; James expects to reach his wife before labor escalates; Logan expects to stay anonymous in a crowd while selling his motorcycle. The breakdown pulls every plan out of alignment, and the story uses that to explore how chance can reroute a life without asking permission.

What looks like wasted time turns into the exact space where transformation happens. Reed meets Kellie only because he waits at the terminal; their connection grows through unplanned wandering and shared hours.

Avery meets Harrison only because he lands behind her in line and then again in the cafeteria; the conversation that begins as a way to kill time becomes a doorway to a relationship she thought she had closed off. Beth and Logan confront their marriage because Olivia literally runs toward him on the deck; without the delay, that collision never occurs.

Virginia’s reconciliation survives because the delay forces both twins to admit how much they still want each other. Even James’s daughter is born into a soundscape of strangers counting and singing, a story that will forever attach meaning to that day.

The one-year-later reunion emphasizes that change is often recognized only in retrospect. None of the characters could predict that a mechanical failure would become a turning point; they can only see later that life sometimes grows through interruption.

The holiday setting strengthens this theme because Christmas is a time when people cling to tradition and timetables, hoping to control joy. A Ferry Merry Christmas gently argues the opposite: joy often arrives through the unscheduled, the inconvenient, the moment you did not arrange.

The delay teaches the characters to stop treating time as merely something to spend efficiently and to notice it as something that can open unexpected doors. In that sense, the stalled ferry is not just a plot device.

It is a reminder that the hours we resist most may be the ones that change us.