A Great Marriage by Frances Mayes Summary, Characters and Themes

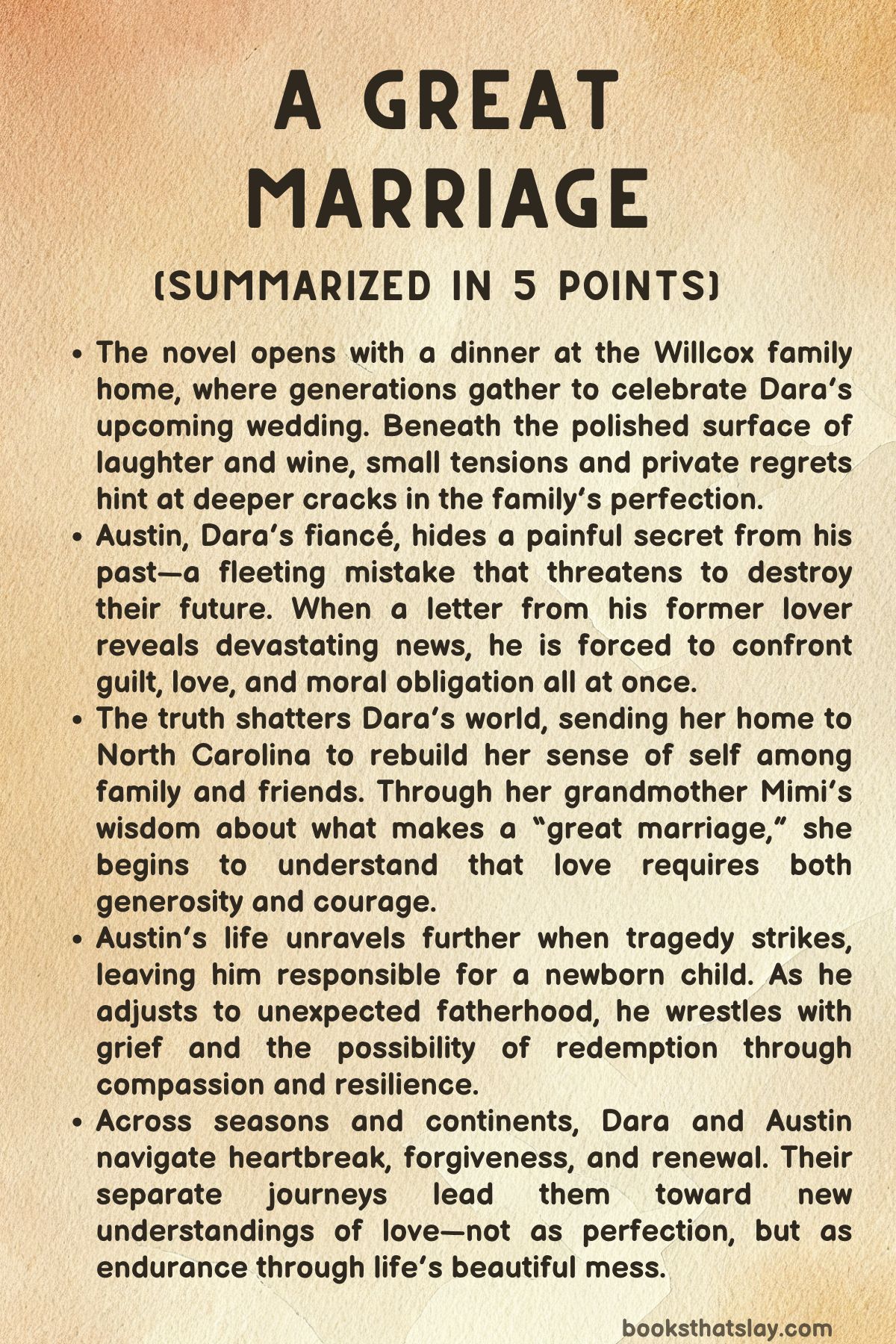

A Great Marriage by Frances Mayes explores the complexities of love, fidelity, and the constant evolution of human connection. Set against the backdrop of Southern charm and cosmopolitan life, the novel follows Dara Willcox and her fiancé Austin Clarke as they prepare for their seemingly perfect wedding.

Beneath the surface of celebration, however, lie secrets that threaten to unravel not only their future but also the harmony of their families. Through interwoven perspectives of mothers, daughters, and lovers, Mayes examines how people navigate betrayal, forgiveness, and the enduring hope for renewal in relationships that are anything but simple.

Summary

The story begins in Hillston, North Carolina, where Lee and Rich Willcox host an intimate dinner to celebrate their daughter Dara’s upcoming marriage to Austin Clarke, a young architect. The evening, filled with laughter and warmth, takes a brief awkward turn when Lee spills wine on the tablecloth—a small imperfection that mirrors her lifelong desire for order and control.

Around the table sit family and friends: Lee’s mother, Charlotte “Mimi” Mann, Dara’s close friends Moira and Mei, and Austin’s architect colleagues, Amit and Luke. Though everything appears harmonious, subtle tensions simmer beneath the pleasant conversation.

That night, each character’s private reflections reveal the emotional depth behind the family’s polished surface. Lee, unable to sleep, recalls Dara’s troubled romantic past and the loss of her stillborn son, Hawthorn, years earlier.

She sees Austin as the ideal partner for her daughter—steady, kind, and reliable—but also feels that her attachment to him fills an emotional void left by her lost child. Her husband, Rich, lies beside her, content yet preoccupied with thoughts of aging and an impending reporting trip to Alaska, where he will cover an oil spill.

The environmental disaster hints at emotional contamination that soon mirrors their family’s own turmoil.

Charlotte, Lee’s outspoken mother, reflects on her past marriages and complicated love life. Now seeing an aging naval officer, she views Austin as decent but senses deeper unrest within him.

She recognizes that Lee’s perfectionism is born from her own past mistakes and a generational effort to mend emotional fractures through appearances of stability. Meanwhile, Dara lies awake in her childhood bedroom, reminiscing about growing up by the Eno River and her early days with Austin—moments filled with laughter, spontaneity, and a shared passion for art and discovery.

She dreams of a joyful future, convinced their marriage will be effortless.

Outside that same night, Austin shares a quiet talk with Lee about family quirks and wedding plans. Beneath his charm, he hides a burden: memories of Shelley Suri, a former lover from Cambridge University.

Months earlier, he had spent a drunken night with her after their breakup, a lapse he deeply regrets. When he later received a message from Shelley asking to speak, he ignored it, believing the past was buried.

Yet guilt lingers, shadowing his engagement.

Soon after, Austin receives a letter from Shelley that shatters his composure. She confesses she is seven months pregnant with his child and gravely ill.

The pregnancy, she writes, was meant as a private solace, a way to preserve part of him after he left her. Torn between shame and dread, Austin realizes that one reckless night has ruined the future he imagined with Dara.

Alone in his apartment, he grieves not only for his mistake but for the innocence of his love.

Back in Washington, D. C., Dara senses his distance but assumes it’s wedding stress. When Austin finally confesses the truth, she is devastated.

She tells him to sleep in the guest room, and by morning, she’s gone—leaving behind his mother’s engagement ring and a note saying the wedding is off. Her parents, shocked but compassionate, welcome her home without pressing for details.

Gossip spreads through their small community, while Dara withdraws into reflection and grief.

To clear her mind, Dara visits her grandmother Mimi on Indigo Island. Mimi, known for her books The Good Marriage and The Good Divorce, offers wisdom on relationships—that love requires generosity and imagination.

Dara listens but feels uncertain whether forgiveness is possible. On her way home, she meets John Harrison, a painter from her childhood summers.

She confides everything to him, and their conversation brings her a rare sense of peace. John paints her portrait, capturing the sorrow and quiet resilience beneath her calm.

Austin, in the meantime, struggles alone. He tells his friend Amit about Shelley’s pregnancy and his shattered engagement.

When Shelley later dies giving birth to a son, Hawthorn, Austin is consumed by guilt but resolves to take responsibility for the child. Dara learns of Shelley’s death and Austin’s new role as a single father.

Though she still loves him, she admits she cannot imagine helping raise another woman’s child. They part with tenderness but uncertainty.

Months pass. Dara focuses on rebuilding her life—meeting with friends, taking comfort in her parents, and accepting John’s invitation to help restore his family’s seaside inn, The Palms.

The project becomes a turning point. Working among artists and surrounded by coastal light, Dara regains a sense of purpose and begins to imagine a new path.

Meanwhile, in London, Austin adjusts to fatherhood with the help of his sister Annsley and a kind nanny. He finds solace in caring for baby Hawthorn, slowly rediscovering equilibrium amid the quiet rhythm of domestic life.

Time heals them in different ways. Dara decides to pursue law school in Georgetown, while John departs for an art fellowship in Rome.

Both she and Austin continue to correspond sporadically, their connection alive but fragile. When they finally meet again months later in London, Dara visits Austin unexpectedly.

They fall easily into conversation about art and architecture, and old feelings resurface. Austin introduces her to Hawthorn, whose innocent presence softens her heart.

That night, they share a meal, memories, and eventually reconciliation.

Later, the narrative brings the extended families together once more at Redbud, the Willcox home, for Christmas. Lee is recovering from a serious accident, and her survival has prompted her to embrace change and creativity anew.

Amid laughter, gifts, and holiday traditions, Dara and Austin’s love rekindles fully. During the celebration, Reverend Wilson arrives unexpectedly, and in a spontaneous decision, Dara and Austin marry before family and friends.

Their vows are unscripted but sincere, a declaration of acceptance rather than perfection.

As dawn approaches, the newlyweds prepare to leave North Carolina for Washington, D. C., with Hawthorn in tow. Lee and Rich watch them drive away, their daughter’s future uncertain but chosen.

The story closes on a note of renewal: through loss, betrayal, and reconciliation, each character learns that true love is not flawless but made stronger by forgiveness and courage to begin again.

Characters

Lee Willcox

Lee Willcox stands at the emotional and symbolic center of A Great Marriage, embodying the tension between order and chaos, control and acceptance. A writer by profession, she lives in constant negotiation between the need to curate perfection and the inevitability of imperfection that life insists upon.

The dinner scene where she spills wine on the white tablecloth captures her character’s essence—a woman whose meticulous nature cannot shield her from the accidental messes that mirror emotional realities. Lee’s reflections on her lost son, Hawthorn, reveal a grief sublimated into her drive to preserve harmony within her family.

Her attachment to Austin, her daughter’s fiancé, is complex: she sees in him the son she lost, the stability she craves, and a vessel of redemption for the past. Yet her perfectionism often borders on control, revealing her fear of life’s unpredictability.

Over the novel, her journey is one of gradual surrender—accepting imperfection, forgiving the inevitable, and rediscovering vitality through both crisis and recovery.

Rich Willcox

Rich Willcox serves as Lee’s emotional counterpoint: pragmatic, affectionate, and grounded. A journalist who travels widely, his professional life contrasts with Lee’s inward literary world.

He symbolizes steadiness amid turbulence, often mediating between his wife’s anxieties and his daughter’s emotional upheavals. Though deeply loving, Rich occasionally drifts into quiet resignation, accepting the erosion of time and routine.

His inner monologues expose a man who cherishes family yet wrestles with aging and the loss of passion. His experiences as a reporter—facing environmental disasters and human frailty—mirror the moral and emotional contamination that creeps into his domestic world.

By the novel’s end, Rich’s compassion and resilience form the moral backbone of the family, underscoring that endurance, not perfection, sustains love.

Charlotte “Mimi” Mann

Charlotte, or Mimi, is both matriarch and philosopher of love in A Great Marriage. A flamboyant psychologist and author of books like The Good Marriage and The Good Divorce, she has lived a life of emotional experiments—multiple marriages, countless analyses, and a defiant pursuit of self-knowledge.

Her charm lies in her contradictions: irreverent yet wise, vain yet perceptive. Mimi’s relationship with Lee is a generational echo—Lee’s quest for control arises from Mimi’s chaos.

In her interactions with Dara, she becomes a mirror of possibility and warning, offering advice shaped by experience and failure. Her belief that a “great marriage” requires generosity and imagination transcends her own missteps.

Through her, the novel interrogates whether love can ever be entirely rational or healed through understanding. Mimi represents a life lived vividly, even if imperfectly, and her unapologetic embrace of the messiness of love provides the thematic foundation for the story’s title.

Dara Willcox

Dara is the novel’s beating heart—a woman whose idealism about love collides painfully with betrayal and loss. Intelligent, independent, and imaginative, she begins as a bride-to-be glowing with the promise of romance and ends as a woman tempered by sorrow and renewal.

Her journey charts the transformation from innocence to maturity. The discovery of Austin’s infidelity and the existence of his child devastate her, not merely because of betrayal, but because it shatters her belief in the perfect symmetry of love.

Her recovery is gradual and deeply human: through solitude, friendship, and rediscovery of purpose, Dara learns to embrace complexity. Her bond with John Harrison brings both comfort and self-reflection, marking her passage into a quieter, wiser understanding of love.

By the novel’s close, when she reunites with Austin, Dara’s forgiveness feels earned—no longer an act of naivety, but a conscious acceptance of love’s contradictions.

Austin Clarke

Austin Clarke embodies both the novel’s tragedy and its redemption. As a gifted architect, he is drawn to structure and design—yet his life collapses under the weight of emotional architecture he cannot sustain.

His love for Dara is sincere and luminous, but his weakness in the face of temptation marks him deeply human. His affair with Shelley Suri and the resulting pregnancy shatter the fragile ideal of perfection surrounding him.

Austin’s guilt and self-reproach shape his descent into moral reckoning, and Shelley’s death forces him to confront responsibility in its purest form—fatherhood without choice. Caring for his son, Hawthorn, becomes his atonement.

Through this act, he redefines love not as desire or escape but as endurance and care. By the time Dara reenters his life, Austin has evolved into a man capable of the depth and steadiness that once eluded him.

His story completes the book’s cycle of chaos turned into creation—love reborn through accountability.

Shelley Suri

Shelley Suri, though largely absent in person, haunts A Great Marriage as both specter and catalyst. An Indian-British architect, she represents unfulfilled longing and the consequences of emotional excess.

Shelley’s relationship with Austin is a collision of passion and obsession, rooted in cultural dislocation and personal fragility. Her letter—confessing her pregnancy and illness—transforms the narrative, merging guilt with tragedy.

Shelley’s motivations are layered: she is both manipulative and sincere, using motherhood as redemption and as a means to keep Austin bound to her memory. Her death, during childbirth, gives her a paradoxical immortality—her child ensures that she remains forever intertwined with the lives she disrupted.

Shelley personifies the destructive beauty of love untempered by reason.

John Harrison

John Harrison enters the story as a symbol of healing and artistic introspection. A painter rooted in nostalgia and observation, John reconnects with Dara when she is at her most fragile.

His calm empathy and creative sensibility offer her a refuge from chaos, reminding her of the simple human act of witnessing. Through their conversations and shared time at The Palms, John becomes a catalyst for Dara’s renewal.

His ability to see and render beauty in pain echoes the novel’s broader theme—the transformation of loss into art, of fracture into form. Though their romance remains fleeting, his presence helps Dara regain trust in herself and in love’s possibility.

John’s quiet decency and aesthetic sensitivity contrast sharply with Austin’s turmoil, making him a figure of balance and peace.

Hawthorn Clarke

Hawthorn Clarke, the child of Austin and Shelley, carries the novel’s deepest symbolism. Named after Lee’s lost infant, he bridges generations of grief, love, and rebirth.

Though only a baby, he becomes the vessel through which forgiveness and continuity flow. To Dara, he initially embodies the unbearable evidence of betrayal; to Austin, he represents both punishment and salvation.

As the story unfolds, Hawthorn’s innocence softens the adults around him, transforming guilt into grace. His presence at the novel’s end—during the impromptu Christmas wedding—turns him into a silent witness to reconciliation.

In Hawthorn, the novel finds its closure: life emerging from loss, imperfection giving birth to hope.

Themes

Perfection and the Fragility of Order

In A Great Marriage, Frances Mayes presents perfection not as an attainable ideal but as a brittle construct that masks human vulnerability. Lee Willcox’s fixation on flawlessness—whether in her home, her daughter’s wedding, or her family’s image—symbolizes the deep unease that underlies social harmony.

The novel begins with a dinner scene in which a spilled glass of wine becomes a quiet metaphor for imperfection intruding on the illusion of control. For Lee, order functions as both defense and denial; it keeps chaos at bay but also prevents authentic connection.

Her pursuit of perfection extends to Dara’s life, especially her marriage, which she imagines as a continuation of the ideal domestic world she has built. Yet the novel dismantles this illusion through the revelation of Austin’s betrayal and Shelley’s pregnancy, events that fracture every notion of ideal love and family.

Mayes uses these ruptures to suggest that perfection, far from being sustaining, isolates individuals within expectations they cannot fulfill. As Lee later learns after her accident, life’s beauty lies in its mess—the unpredictability, pain, and forgiveness that allow growth.

The fragility of her carefully arranged world exposes a broader truth: perfection is not a state of purity but a form of paralysis. Only when the characters confront disorder—the “mess,” as Beckett’s quote in the hospital scene frames it—do they begin to live truthfully.

Through Lee’s evolution and the novel’s cyclical structure of breakdown and renewal, Mayes critiques the cultural reverence for composure and celebrates imperfection as the only space where love and resilience can coexist.

Betrayal, Guilt, and Moral Responsibility

Austin’s moral crisis forms the emotional core of the novel, turning A Great Marriage into an exploration of human frailty and ethical reckoning. His one-night relapse with Shelley transforms what was once a luminous love story with Dara into a study of conscience.

Mayes renders his guilt not as an external punishment but as a corrosive force that dismantles his identity. Austin’s initial silence reveals how betrayal thrives in secrecy; his inability to confess early to Dara mirrors his deeper fear of losing the image of himself as honorable and devoted.

When Shelley’s pregnancy becomes known, his guilt evolves into responsibility, forcing him to confront not only the consequences of his actions but also the moral weight of fatherhood. The birth of his son, Hawthorn, and Shelley’s death place him in a paradox—his greatest failure has produced an innocent life he must now protect.

Mayes uses this paradox to probe the limits of redemption: whether love can survive when trust has been irreparably damaged, and whether remorse can be transformed into moral courage. Austin’s eventual care for Hawthorn represents an act of atonement rather than absolution.

His grief, exhaustion, and quiet endurance suggest that integrity is not restored through confession alone but through sustained responsibility. Dara’s later forgiveness, though hesitant, emerges from recognizing this transformation.

Betrayal in the novel is not portrayed as a singular act but as a chain of human misjudgments that demand empathy rather than condemnation. Through Austin’s journey, Mayes redefines moral failure as an invitation to maturity—painful, humbling, and essential for genuine love.

Love, Forgiveness, and Renewal

Love in A Great Marriage is portrayed as mutable, resilient, and shaped by forgiveness. Rather than idealizing romantic union, Mayes presents it as a dynamic process of breaking and rebuilding.

Dara’s journey from joy to heartbreak and eventual reconciliation with Austin illustrates the necessity of forgiveness not as moral weakness but as an act of courage. When Dara learns of Austin’s infidelity and its devastating consequences, her response—silence, withdrawal, and eventual self-reinvention—marks her passage from innocence to emotional maturity.

Through her time with Mimi, John, and her friends, she discovers that love’s endurance lies not in purity but in understanding. Forgiveness, in this sense, becomes creative: it allows her to reimagine her life without erasing pain.

Austin’s steadfast care for his son deepens this theme; Dara’s final acceptance of both father and child at Christmas is less about reconciliation than recognition—that love, to remain alive, must embrace imperfection. Mayes positions forgiveness as the novel’s moral center, countering the destructiveness of betrayal with the healing power of empathy.

Renewal emerges in small, quiet gestures—letters, meals, shared laughter, the rebuilding of a seaside inn. Each act signifies the reclamation of hope from loss.

The closing scene, with Dara and Austin’s impromptu wedding, transforms forgiveness into celebration: a declaration that life, despite its wreckage, can still yield joy. Through this progression, Mayes suggests that great love is not one that remains unbroken but one that endures the breaking and learns to begin again.

Family Legacy and Generational Influence

The multigenerational dynamic among Charlotte, Lee, and Dara anchors A Great Marriage in a meditation on inheritance—emotional, psychological, and moral. Each woman embodies a response to the past: Charlotte’s flamboyant restlessness, Lee’s compulsive order, and Dara’s oscillation between control and surrender.

Mayes constructs their relationships as mirrors reflecting the cyclical patterns of love and self-protection passed from mother to daughter. Charlotte’s multiple divorces and outspoken independence haunt Lee, whose quest for stability becomes a corrective to her mother’s volatility.

Yet Lee’s obsession with structure only perpetuates anxiety rather than peace. Dara inherits this burden of expectation but ultimately transcends it by embracing uncertainty.

Her decision to rebuild her life, to work at The Palms, and to accept both love and loss marks a generational shift—from fear of imperfection to acceptance of complexity. The conversations between Mimi and Dara about what constitutes a “great marriage” provide the philosophical frame for this evolution: that endurance, imagination, and generosity define family more than adherence to form.

The later scenes, where the family gathers after Lee’s accident, underscore the healing power of shared vulnerability. Instead of control or rebellion, connection becomes the legacy they pass forward.

Mayes portrays family not as static lineage but as an ongoing dialogue—between what is inherited and what is chosen. The transformation of these three women illustrates how understanding one’s family history allows renewal rather than repetition.

Through them, the novel asserts that love matures only when individuals reconcile with the flawed legacies that shaped them.

Resilience and the Art of Living Forward

Resilience serves as the final unifying theme of A Great Marriage, threading together the emotional recoveries of its characters into a meditation on endurance. After betrayal, death, and illness, the Willcox and Clarke families learn to rebuild meaning through continuity rather than erasure.

Mayes treats resilience not as stoicism but as creative adaptation—a willingness to reimagine life amid chaos. Dara’s rebuilding at The Palms symbolizes this transformation: a literal restoration of a space that mirrors her internal repair.

Austin’s evolution into a devoted single father parallels hers, showing that survival involves accepting responsibility and reshaping identity. Even Lee, recovering from her accident, embraces imperfection and spontaneity after years of rigidity.

The novel’s closing Christmas scenes emphasize that healing is collective; music, laughter, and shared meals restore what isolation once eroded. The impromptu wedding embodies this renewal—a spontaneous act that rejects the earlier obsession with control.

Through these converging arcs, Mayes proposes that resilience is an art form rooted in love, forgiveness, and imagination. To live forward, her characters must accept that beauty and chaos coexist; that the future is not a return to the past but a continuation of it, reshaped by grace.

In affirming life after loss, the novel honors human endurance as its highest expression of faith—not in perfection or fate, but in the stubborn, hopeful act of beginning again.