A Rome of One’s Own Summary and Analysis

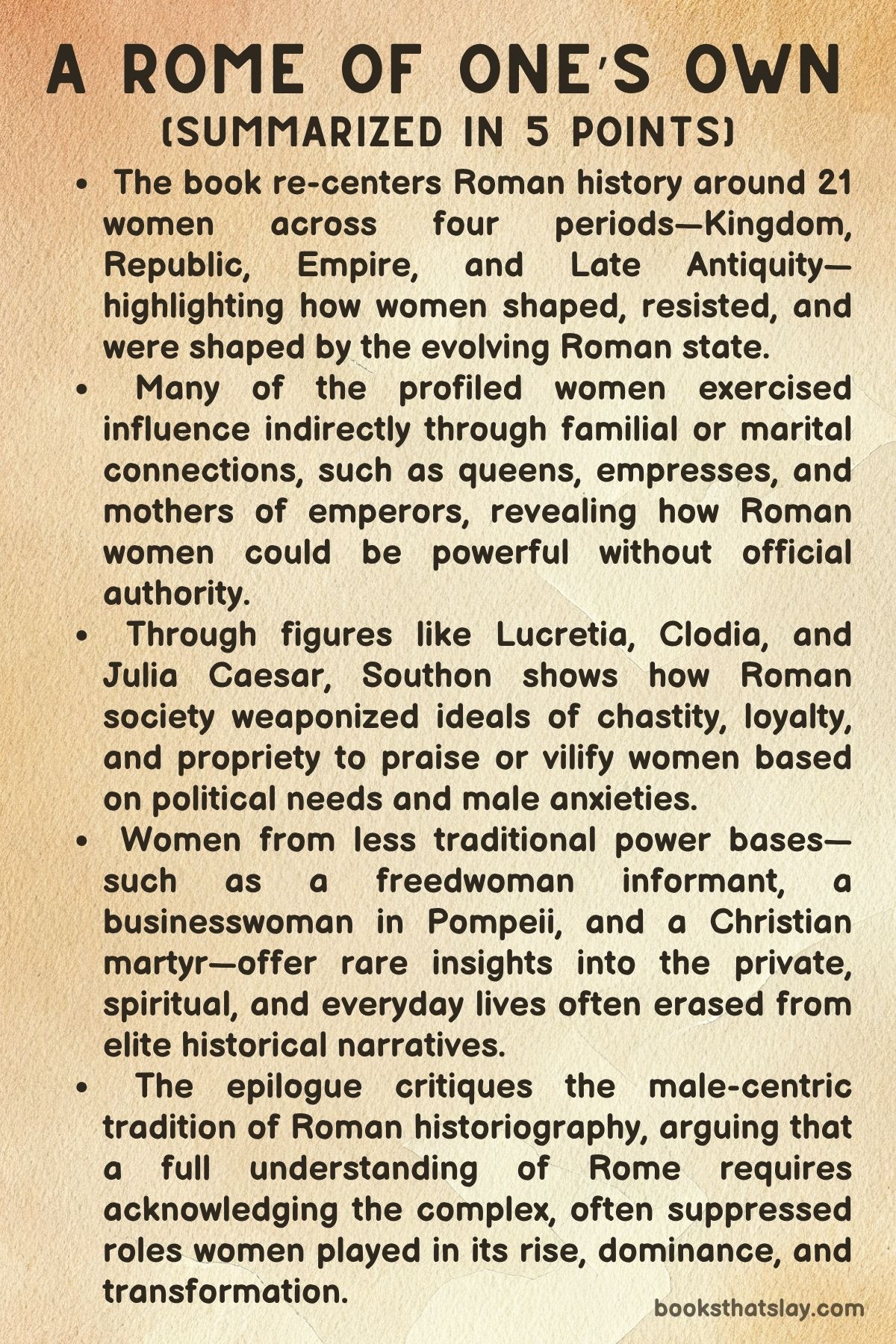

A Rome of One’s Own by Emma Southon is a bold, irreverent, and deeply engaging reexamination of Roman history through the lives of 21 women. These women lived across its major political phases—from the mythic Kingdom to Late Antiquity.

With sharp wit and an unapologetically feminist lens, Southon dismantles the traditional, male-centered version of Roman history that dominates our understanding. Instead of generals, emperors, and senators, she offers up sex workers, saints, rebels, queens, and empresses—women whose stories were often ignored, misunderstood, or misrepresented by the male historians of their time.

The book is not just a story. It’s a lively declaration that women’s lives mattered in the making and breaking of Rome.

Summary

The book opens with the semi-legendary figures of Tarpeia and Hersilia during the founding of Rome. Tarpeia, remembered as a traitor, is killed by the Sabines after betraying Rome, while Hersilia helps mediate peace between the warring Sabines and Romans.

These stories highlight early Roman ideas of loyalty, betrayal, and female influence in shaping civic order. Tanaquil, an Etruscan queen, ensures her husband and later her son-in-law ascend to the Roman throne, using her reading of omens and social intelligence.

She is a striking example of how women exercised political power behind the scenes. Lucretia and Tullia offer contrasting tales during Rome’s transition to a republic.

Lucretia’s rape and suicide become foundational myths of Roman virtue and resistance to tyranny. Tullia, known for conspiring to murder her father and seize the throne with her husband, becomes a symbol of immoral female ambition.

The Vestal Virgin Oppia is executed after being accused of breaking her vow of chastity. Her story reflects how women were often scapegoated in times of crisis.

Hispala Faecenia, a freedwoman and former sex worker, alerts the Senate to the Bacchanalia cult’s activities, leading to a massive state crackdown. She plays a vital role as a truth-teller from society’s margins.

Clodia, a scandalous noblewoman, is publicly condemned by Cicero for her alleged immorality during a court trial. Her portrayal reflects elite anxieties about women who defied societal norms.

Turia, by contrast, is praised by her husband in a funerary inscription for her loyalty, sacrifice, and courage. She is idealized as the dutiful Roman matron.

Julia Caesar, daughter of Augustus, is married off multiple times for political alliances. She is later exiled for perceived moral failings.

Her fall illustrates the impossibility of navigating elite female virtue under imperial scrutiny. Queens Cartimandua and Boudicca, both in Roman Britain, present contrasting relationships with Roman rule—one cooperating, the other violently rebelling.

In Pompeii, Julia Felix thrives as a landowner and businesswoman. She represents women in economic life.

Sulpicia Lepidina, whose letters were found at Vindolanda, offers a rare window into the emotional and domestic world of Roman military wives. Poet Julia Balbilla carves her verses on Egyptian monuments while traveling with Emperor Hadrian.

She shows that women could leave intellectual marks in public spaces. Perpetua, a Christian martyr, defies Roman religious norms and embraces death rather than abandon her faith.

She leaves behind a powerful personal narrative. Julia Maesa and her daughter Julia Mamaea orchestrate the rise of emperors within their family.

They wield influence at the heart of Roman power, though their hold is ultimately shattered by military politics. Zenobia, queen of Palmyra, openly challenges Rome by expanding her empire before being defeated and memorialized in legend.

Melania the Elder abandons her wealth and embraces ascetic Christianity. She founds monasteries and redefines elite female roles through religious devotion.

Galla Placidia navigates an empire in collapse. She serves as a regent, mother, and political actor at the crumbling edge of Roman authority.

The epilogue ties these stories together by emphasizing the historical silence imposed on women. Southon argues that Rome was never just a man’s world.

Including these women in the narrative changes how we understand power, culture, and identity in the ancient world.

Characters

Tarpeia

Tarpeia is emblematic of the Roman distrust of female betrayal. Her infamous act of leading the Sabines into the Roman citadel—allegedly for gold—ends in her own execution, not by Romans but by those she aids.

Her story becomes an enduring lesson in greed and treason, particularly when committed by women. Tarpeia’s legacy is not just personal tragedy but a societal parable, where her motives are overshadowed by the consequences, making her a scapegoat for anxieties around loyalty and gendered power.

Hersilia

Hersilia functions as the archetype of the peacemaker wife, using her familial role to mediate between warring peoples. As Romulus’ wife and a Sabine, her dual identity allows her to become a unifier, bridging conflict through maternal authority.

She stands in contrast to Tarpeia by showing the idealized, virtuous woman whose diplomacy helps establish social cohesion. Hersilia symbolizes how Roman femininity was often equated with the ability to smooth political tensions through domestic virtue.

Tanaquil

Tanaquil’s narrative reveals how women could exert power behind the scenes, particularly through their husbands. As a noblewoman of Etruscan origin, she operates within the religious and prophetic framework of Roman politics, using omens to legitimize her husband and son-in-law’s rule.

Tanaquil’s actions show the backroom orchestration of monarchy through maternal foresight and manipulation. Though invisible in formal roles, she is deeply enmeshed in the machinery of dynastic transition.

Lucretia

Lucretia embodies the ideal Roman matron, whose chastity becomes both a personal virtue and a political weapon. Her rape and suicide catalyze the overthrow of monarchy and the birth of the Republic.

Yet, she becomes less a person and more a mythic symbol of Roman virtue. Lucretia’s story illustrates how women’s bodies and moral choices were often co-opted into grand narratives, used to justify sweeping societal change while silencing the individual trauma.

Tullia

Tullia stands as the antithesis of Lucretia. She murders her father and marries her brother-in-law to consolidate power, embodying unchecked female ambition.

Her manipulation and violence make her a cautionary figure against women wielding overt political influence. Tullia’s legacy is one of revulsion and fear—used to underscore the dangers of women overstepping moral and political boundaries.

Oppia

As a Vestal Virgin punished for breaking her vow of chastity, Oppia’s fate reflects the intense symbolic and civic burden placed on religious women in Rome. Buried alive, she is both a victim and a vessel—her body punished to cleanse the state’s perceived impurity.

Oppia’s story exposes the impossibility of autonomy for such women, where divine and civic duties collide with mortal consequences.

Hispala Faecenia

Hispala, a freedwoman and former sex worker, shows that marginal women could wield surprising influence in moments of crisis. Her revelation about the Bacchanalian cult helps the Senate dismantle what it sees as a subversive network of unregulated female religious activity.

Hispala’s credibility is paradoxical: she’s valued for her information yet reviled for her origins. She stands as a reminder of how the Roman state both feared and exploited female agency at the margins.

Clodia

Clodia defies every norm of Roman female decorum—she is educated, wealthy, sexually autonomous, and politically visible. Attacked by Cicero as the “Palatine Medea,” she becomes a scapegoat for elite female transgression.

Her trial becomes more about her reputation than the legal matter itself. Clodia’s narrative exposes how anxieties about gender, class, and sexual agency intersected, and how the courtroom became a theatre for moral judgment.

Turia

Though anonymous in her funerary inscription, Turia is immortalized through her husband’s praise. She is celebrated for her loyalty, endurance, and active participation in his political survival.

Her life story, as told by him, turns her into the ideal Roman wife—supportive, courageous, and morally upright. Turia’s characterization reveals the narrow lane available for female heroism: it must remain aligned with the preservation of male legacy.

Julia Caesar

Julia, Augustus’ daughter, serves as a political pawn in the dynastic games of early empire. Despite her strategic marriages and potential, she is cast out for alleged promiscuity, becoming a casualty of Augustan sexual morality.

Her treatment reflects the fragility of women’s public roles in Rome. Julia’s personal tragedy is emblematic of Rome’s contradictions around purity and propaganda.

Cartimandua and Boudicca

These two Celtic queens reflect divergent responses to Roman imperialism. Cartimandua cooperates with Rome, using alliance and betrayal to maintain power, while Boudicca violently rebels after Roman abuse.

The former is dismissed as untrustworthy; the latter is feared and mythologized. Their contrasting legacies highlight the racial and cultural dynamics at play in Roman views of foreign femininity.

Julia Felix

Julia Felix, a property-owning entrepreneur in Pompeii, offers a rare look at economic independence among elite women. Her estate, leased for public and private use, shows the legal and commercial freedoms some Roman women possessed.

Julia’s life suggests that in times of relative stability, women could operate publicly and materially outside the constraints of marriage or familial dependence. Her visibility in the archaeological record challenges the narrative of complete female domesticity.

Sulpicia Lepidina

Through her letters found on the Vindolanda tablets, Sulpicia provides a deeply personal glimpse into military life from the perspective of an officer’s wife. Her correspondence mixes affection, daily concerns, and familial planning.

She reveals emotional depth and domestic engagement even on Rome’s far-flung frontiers. Sulpicia disrupts the image of Roman women as either absent or passive.

Julia Balbilla

Julia Balbilla asserts her intellectual and cultural presence through inscribed poetry during Hadrian’s travels. Her epigrams blend Greek literary tradition with political flattery, showcasing elite female education and voice.

Though tied to imperial narratives, her work reveals a woman deliberately shaping how she is remembered. Julia Balbilla is notable not just for her words, but for her insistence that they endure.

Perpetua

Perpetua’s martyrdom is unique for its surviving autobiographical record—a young Christian noblewoman who embraces execution rather than renounce her faith. Her prison diary documents a spiritual transformation that redefines Roman identity through Christian virtue.

Perpetua’s defiance is both religious and gendered. She becomes a symbol of transcendence and conviction that challenges the very basis of Roman order.

Julia Maesa and Julia Mamaea

These imperial matriarchs of the Severan dynasty exemplify how women could rule indirectly through familial proximity to power. Maesa orchestrates her grandsons’ rise to emperorship, while Mamaea governs alongside her son Severus Alexander.

Their influence is real but fragile, always contingent on military and political favor. Their eventual downfall underscores the limits of female power in Rome.

Zenobia

Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, leads a short-lived but powerful rebellion against Rome, extending her rule over Eastern provinces. Educated and politically savvy, she declares herself Augusta, adopting Roman imperial titles to legitimize her reign.

Though ultimately defeated, she is admired even in failure. Zenobia complicates Rome’s imperial ideology by embodying both the admired “other” and the dangerous female sovereign.

Melania the Elder

Melania relinquishes immense wealth and status to pursue a monastic life in the East. She represents the shifting axis of Roman femininity—from public virtue to religious piety.

In her asceticism and charity, she pioneers a new model of influence. Melania’s life reflects Christianity’s growing power and the ways elite women could carve new roles through religious devotion.

Galla Placidia

Galla Placidia’s political journey spans barbarian captivity, imperial regency, and dynastic maneuvering. As daughter, wife, and mother to emperors, she governs during Rome’s twilight with considerable autonomy.

Her ability to maintain stability amid fragmentation makes her one of the last figures to embody classical Roman authority. Placidia’s rule, though shaped by male relatives, asserts the possibility of female sovereignty during imperial collapse.

Themes

Power Through Kinship and Marriage

One of the consistent themes in the book is how Roman women could acquire influence through their roles as wives, mothers, sisters, or daughters. These familial relationships became powerful tools, not only in private households but in the mechanisms of state power.

From the mythical Hersilia who uses her domestic position to mediate peace, to historical figures like Tanaquil, Turia, Julia Maesa, and Julia Mamaea, Southon shows that these women operated from within the patriarchal framework to steer political outcomes. However, their power was often contingent upon the men they were attached to, underscoring the limitations placed on female autonomy.

Tanaquil’s manipulation of succession or Mamaea’s co-rule with her son were possible because they remained tethered to male authority. Once those bonds were broken or undermined, their influence often collapsed.

These women were not simply background figures. They played central roles in governance and dynastic continuity, yet their efforts were rarely immortalized with the same dignity as their male counterparts.

Southon’s presentation complicates the idea that Roman women were universally voiceless. She emphasizes how kinship ties were manipulated in service of political agendas.

Still, this power was seen as legitimate only when it was in service to male heirs or dynastic needs, not self-agency. This exposes the fragility and instrumental nature of female influence in Roman society.

The Weaponization of Female Sexuality

Another major theme is how women’s sexuality—whether protected, transgressive, or weaponized—functioned as a focal point of moral, legal, and social anxieties in Roman culture. Southon demonstrates that Roman narratives were obsessed with defining what women should or should not do with their bodies.

Chastity is shown as a deeply political tool. The stories of Lucretia, Oppia, and the Vestals portray female virtue as a linchpin of social order, with any breach regarded as a symptom of broader societal decay.

In contrast, women like Clodia or Julia Caesar are condemned not for their actions alone, but for defying sexual and social decorum. The state used allegations of sexual misconduct to police behavior and consolidate authority, particularly when political stakes were high.

The contrast between Lucretia’s martyrdom and Clodia’s vilification illustrates how women could be lionized or demonized depending on their alignment with Roman ideals of sexual virtue. Even when women were active agents—as in the case of Julia Felix, who owned property and likely had personal relationships outside of patriarchal structures—their independence was frequently framed in terms of sexual morality.

By centering this theme, Southon reveals the double standards and contradictions within Roman values. Women were expected to be sexually pure yet politically useful, desirable yet modest, visible yet silent.

The female body, rather than male ambition, often bore the consequences of political instability and cultural shifts.

Subversion, Resistance, and Female Agency

Southon emphasizes the theme of female resistance—whether direct or symbolic—as an undercurrent to Roman history that both challenges and affirms patriarchal authority. Characters like Boudicca and Zenobia embody outright defiance, leading military campaigns or political revolts that shocked Roman norms and expectations.

Their resistance is portrayed as both fearsome and awe-inspiring, but ultimately punished to reassert the male-dominated status quo. Meanwhile, figures like Hispala and Perpetua represent more intimate forms of resistance: the former, a freedwoman and sex worker, uses her voice to inform the Senate, while the latter embraces Christian martyrdom in opposition to state-sanctioned religious norms.

These acts of defiance are particularly significant because they come from outside the traditional avenues of power. They signify that female agency did not only operate through noble birth or marriage ties but could emerge from personal conviction, moral clarity, or survival.

Yet, resistance is rarely rewarded. It tends to end in death, exile, or erasure, reinforcing the idea that Rome tolerated deviation only within strict boundaries.

Through these stories, Southon reframes Roman history not as a linear progress of male heroes and emperors, but as a dynamic space where women frequently disrupted dominant narratives—at great cost. Even acts that seemed compliant, such as Turia’s protection of her husband or Galla Placidia’s political maneuvering, carry undertones of resistance when viewed against societal expectations.

The theme insists that agency often comes in contested, vulnerable, or paradoxical forms. This is especially true for women in a rigidly hierarchical society.

Memory, Legacy, and Historical Erasure

Southon’s book is acutely aware of the politics of memory and the historiographical gaps that obscure women’s contributions. The theme of historical erasure appears explicitly in the epilogue but runs throughout the chapters, underscoring how the recording of history itself was a gendered act.

Women like Turia are remembered only through a funerary inscription composed by her husband, while Perpetua’s diary survives almost by miracle, offering a rare first-person female voice. Many other women—such as Julia Balbilla or Sulpicia Lepidina—survive through fragmentary records, inscriptions, or casual mentions in male-authored texts.

The effect is that women’s stories are refracted through the perspectives of others, often distorted or truncated. Southon critiques this archival bias by presenting these stories as central, not peripheral, to Roman history.

She argues that what is remembered and what is forgotten reveals the ideological priorities of a culture. The exclusion of women from political records, moral debates, or military annals was not accidental but deliberate, reinforcing the illusion that Rome was a civilization built only by men.

The book becomes a corrective exercise, positioning these women not as curiosities or exceptions but as co-authors of Roman civilization. Southon also challenges modern readers to question how our understanding of antiquity is shaped by those erasures.

This theme makes the book as much about the present-day politics of history-writing as it is about ancient Rome. It encourages a broader reexamination of who gets to be remembered and why.