Again and Again Summary, Characters and Themes

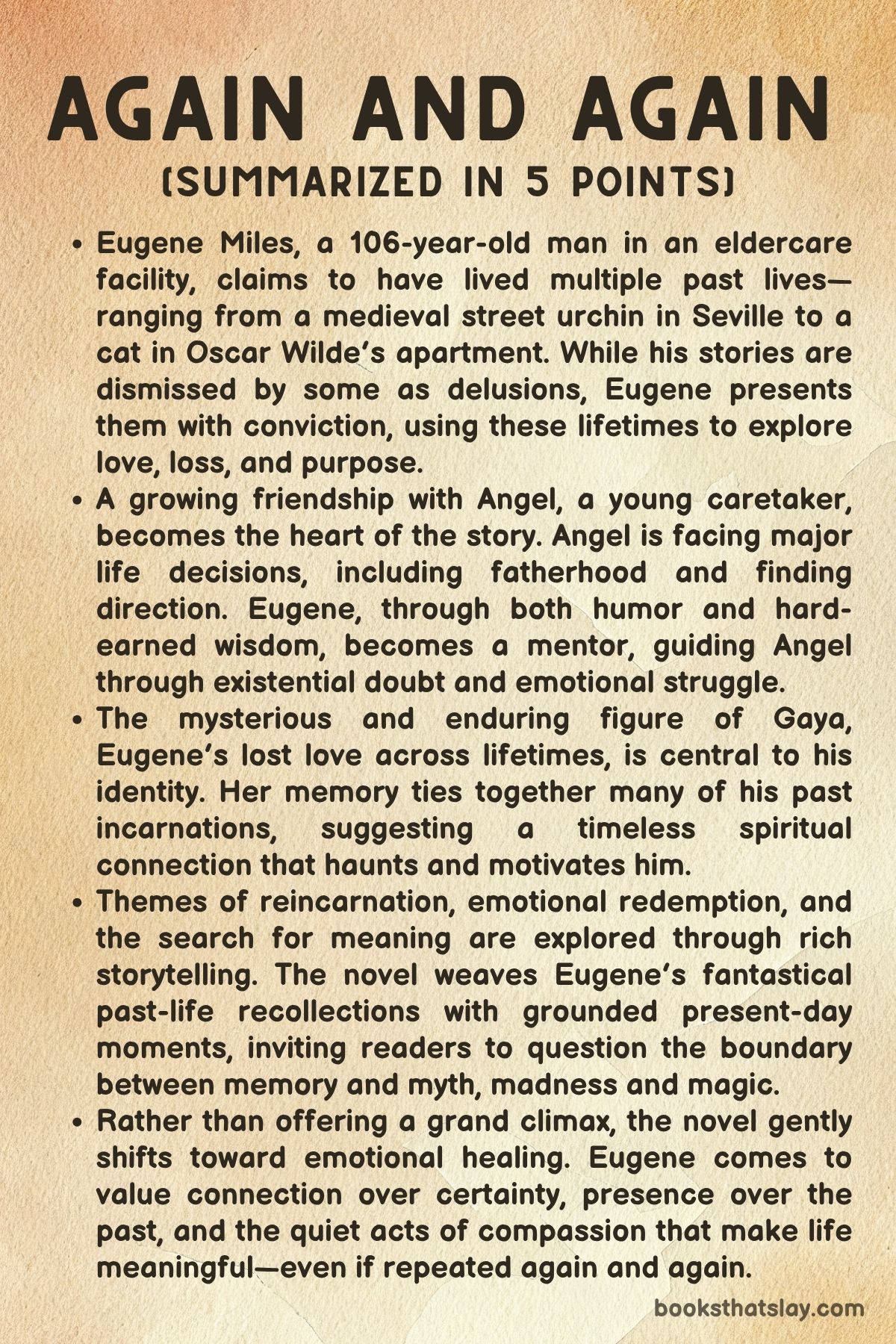

Again and Again by Jonathan Evison is a moving and unconventional novel that blends speculative elements with intimate character study.

It follows Eugene Miles, a 106-year-old man living in a California eldercare facility, who claims to have lived countless past lives across centuries and continents. Through his reflections and a growing friendship with a young housekeeper named Angel, Eugene explores themes of memory, love, identity, and purpose.

This is a story about the search for meaning in a life that refuses to end, and the redemptive power of human connection, even in the most unexpected places.

Summary

Eugene Miles is a 106-year-old man confined to a care facility in California. He claims he’s lived numerous lives over centuries, as people and even as a cat, in places as far apart as medieval Spain, 1930s Los Angeles, and Victorian London.

These recollections are not whimsical fantasies to him—they are deeply emotional memories that form the basis of his identity. At the core of his many lifetimes is a woman named Gaya, whose love has haunted him across generations.

In his current life, Eugene is largely dismissed as senile by the staff and visited occasionally by Wayne, a well-meaning but skeptical mental health worker. Then he meets Angel, a young, tattooed housekeeper with a complicated personal life.

Angel is reluctant to open up, but Eugene sees something in him—vulnerability, curiosity, and perhaps an echo of someone he’s known before. Their slow-growing friendship becomes the anchor of Eugene’s present-day story.

As Angel shares his struggles—particularly an unplanned pregnancy with his girlfriend Elana—Eugene becomes a source of counsel. He tells Angel about his past lives, particularly his life as Euric, a street urchin in medieval Seville.

In that life, he meets Gaya after a botched robbery, and she hides him from guards, offering compassion he doesn’t understand at first. They eventually commit a violent act in self-defense, and flee together.

The experience forms one of Eugene’s strongest memories of love, risk, and sacrifice. Other lives trickle through Eugene’s memories: a lonely boy in Victorville, a gas station worker in Los Angeles, and a cat cared for by Oscar Wilde.

In each existence, he searches for love, belonging, and purpose, yet always ends up grieving and moving on—reborn without closure. Angel, meanwhile, faces personal challenges.

Elana leaves, and Angel doubts his ability to be a good father or to pursue anything more meaningful in life. Eugene pushes him gently toward hope, encouraging him to apply to college and consider a future beyond his current pain.

For the first time in years, Eugene feels relevant, valued, and proud—not because of something he’s done, but because of someone he’s helped. As the relationship deepens, Angel begins to ask Eugene deeper questions about destiny, faith, and legacy.

Eugene continues to explore what his repeated rebirths mean—whether they are punishment, chance, or fate. He wrestles with the possibility that his inability to fully love or forgive may be the reason he keeps returning.

But through Angel, he begins to experience something new: hope not rooted in the past, but in someone else’s future. Their bond grows into something close to family.

Angel brings his young cousin to visit, and Eugene is reminded of the innocence and energy of childhood. He watches Angel take small steps to repair his relationship with Elana, pursue education, and imagine a meaningful life.

Eugene’s final reflections suggest he may not escape the cycle of rebirth, but perhaps the lessons are finally sinking in. Love may not always end in reunion, but it can transform and carry forward into others.

In the final chapters, Eugene doesn’t find Gaya again in the flesh. But her essence—her influence—appears in how he guides Angel, how he forgives himself, and how he accepts the uncertainty of death or rebirth.

The book closes with ambiguity: whether Eugene will die or live again is left open. What’s clear is that he has changed.

He is no longer merely a man remembering. He has become someone who participates, supports, and connects.

The true afterlife, perhaps, is in the love we pass on.

Characters

Eugene Miles

Eugene is the emotional and philosophical core of the novel. At 106 years old, confined to an eldercare facility in California, Eugene is not merely an aging man—he is a man who has lived many lifetimes, both literal and metaphorical.

His claim of past lives serves not only as a narrative device but as a lens through which his trauma, longing, and spiritual exhaustion are interpreted. Whether as Euric the street urchin in medieval Spain, a Victorian-era cat companion to Oscar Wilde, or a broken man in postwar Italy, Eugene wrestles with questions of identity, purpose, and love.

The most enduring aspect of his personality is his eternal yearning for Gaya, the woman who became an archetype of salvation and loss in his many incarnations. His journey from isolation and disillusionment toward connection—particularly through his relationship with Angel—marks a gradual, redemptive arc.

By the end of the novel, Eugene begins to accept impermanence and embraces the idea that life’s worth lies not in grandeur or legacy, but in love, forgiveness, and companionship.

Gaya

Gaya is both a literal character and an ethereal symbol in Eugene’s narrative. Introduced first as a mysterious and kind woman who saves Eugene in medieval Seville, she becomes a recurring figure across his various lifetimes.

Her presence is associated with safety, compassion, and transcendental love—qualities that Eugene returns to again and again, searching for meaning and connection. Gaya is not just a romantic interest but represents Eugene’s moral compass and the emotional peak of each life he remembers.

In many ways, she embodies the concept of soul recognition, as her reappearances in different forms suggest that she, like Eugene, may also be part of a cycle of reincarnation. However, her character is always somewhat elusive—never fully explained, always deeply felt.

This ambiguity strengthens her role as the emotional and spiritual lodestar of the novel.

Angel

Angel begins the story as a seemingly peripheral character—just a young, tattooed housekeeper working at the eldercare facility. But he evolves into Eugene’s closest human connection in his final lifetime.

Initially wary of Eugene’s eccentricities, Angel is gradually drawn into his stories and haunted wisdom. Angel’s own life is fraught with uncertainty: an unplanned pregnancy, financial insecurity, and emotional hesitation.

Yet, through Eugene’s mentoring and storytelling, Angel begins to grow—emotionally and morally. He becomes a stand-in for the future: someone still capable of change, redemption, and forward movement.

Angel’s transformation—from a confused and struggling young man into a determined student and father-to-be—mirrors Eugene’s inner transformation. Their friendship becomes mutually salvational, offering both men a sense of completion that transcends time and age.

Wayne

Wayne serves as a foil to Eugene’s spiritual, mystical worldview. As a well-meaning but rigid mental health worker, Wayne approaches Eugene’s stories with clinical detachment, treating them as symptoms of dementia or fantasy rather than legitimate expressions of a broader human experience.

His skepticism embodies the conflict between rational empiricism and emotional truth. Although often unintentionally patronizing, Wayne’s presence helps sharpen Eugene’s own convictions.

He forces Eugene to articulate what he believes and why, revealing the depth of Eugene’s emotional intelligence and spiritual insight. While Wayne remains mostly unchanged, his conversations with Eugene elevate the narrative tension between science and soul, and between belief and experience.

Elana

Though Elana appears more on the periphery, she represents the consequence and potential of Angel’s life choices. Her initial departure from Angel due to uncertainty about his maturity and commitment acts as a turning point in Angel’s development.

Elana’s willingness to later engage in conversations again suggests not just forgiveness, but the idea that change is possible and relationships can evolve. She is a quiet but pivotal influence whose presence prompts Angel to reflect, recalibrate, and strive toward responsibility.

Her character underscores the novel’s themes of healing, family, and the fragility of human connection.

Oscar Wilde (as seen through Eugene’s past life as a cat)

While Oscar Wilde himself is not a central character, Eugene’s life as a cat companion to the famed poet serves as one of the most whimsical yet poignant sections of the novel. Wilde, through Eugene’s memory, represents an era of flamboyant suffering, emotional repression, and artistic brilliance.

Eugene’s time as Wilde’s cat illustrates how even in lives where he is not human, he remains tethered to human emotion and loss. Wilde’s character, seen through this lens, is melancholic and lonely, echoing the novel’s theme of being both loved and unseen.

Themes

Memory and the Weight of Time

One of the most prominent themes in Again and Again is the burden of memory stretched across lifetimes. Eugene Miles carries the emotional residue of centuries lived, each life layered with experiences, failures, and unresolved longings.

Unlike ordinary memory, which often fades or becomes unreliable, Eugene’s recollections are vivid and persistent, defining his present reality more than the actual moments unfolding around him. His consciousness exists in a kind of temporal overlap, where past and present constantly intrude upon one another.

This accumulation of memory becomes both a source of richness and torment, for it denies him the relief of forgetfulness. He remembers wars, love, betrayal, enslavement, and even the mundane aspects of obscure lives—experiences that shape his philosophy and worldview.

Yet, this endless chain of remembrance isolates him from others, particularly those like Wayne, who interpret his stories as either mental illness or senile fantasy. Eugene’s memories resist rational explanation and clinical frameworks; they carry a soulful truth that challenges conventional boundaries of time.

Through his internal monologue and storytelling, the novel explores how memory, when not linear or limited to a single lifetime, can distort a person’s sense of self and reality. Time, for Eugene, is not a river flowing forward—it is a whirlpool that traps him in moments of beauty and regret, constantly reminding him of what was and what never truly ended.

This theme ultimately raises the question: can one truly live in the present when the past is not behind but still alive within?

Reincarnation and the Quest for Redemption

Reincarnation is not merely a narrative device in Again and Again but the philosophical engine that drives Eugene’s existential crisis. Through the repeated cycles of birth and rebirth, Eugene is forced to confront his own moral and emotional shortcomings.

Each life presents an opportunity not just to begin anew but to correct some spiritual or emotional failure from before. However, Eugene is not certain whether reincarnation is a blessing or a curse.

The idea that he may be living again and again because he has yet to fulfill some higher purpose or pass some moral test haunts him deeply. He speculates on his own guilt—whether it was cowardice, selfishness, or the inability to fully love—that has tethered his soul to the world.

The consistency of Gaya’s presence across these lives acts as a symbol of what he continually strives for: an unattainable emotional and spiritual connection that might release him from this eternal recurrence. But reincarnation is not presented as a romanticized journey toward enlightenment; it is exhausting, confusing, and alienating.

Eugene’s despair is not rooted in fear of death but in the exhaustion of life’s repetition without resolution. The novel subtly critiques the notion that time alone leads to healing.

Instead, it suggests that true redemption comes only through meaningful connection, courage to change, and acts of love untainted by fear. Whether or not Eugene is granted another life by the end of the novel is left ambiguous.

But what becomes clear is that his redemption lies not in escaping the cycle but in finally learning to live within it with grace.

Love as Eternal and Transformative

Love is the spiritual nucleus of Again and Again, both grounding and unmooring Eugene across lifetimes. His connection to Gaya is not merely romantic; it transcends categories of time, identity, and even bodily form.

Whether as Euric the street thief or Eugene the elderly man, his longing for Gaya remains unchanged—an emotional compass pointing to a lost ideal. This love is both a source of joy and a persistent ache, as it remains unresolved and constantly out of reach.

The novel asks whether true love is something that must be consummated in a traditional sense or whether its essence lies in its endurance across space and time. Eugene’s love for Gaya is counterbalanced by his emerging bond with Angel, which unfolds not romantically but in the realm of mentorship and chosen family.

Here, the novel makes a profound statement: love need not be tied to possession, passion, or permanence to be transformative. Through Angel, Eugene experiences a kind of redemption that romantic love alone could not provide—a sense of purpose, emotional reciprocity, and the act of nurturing.

Love, in this novel, is shown to be as multifaceted as life itself. It is romantic, parental, platonic, and spiritual, and it functions as both a mirror and a teacher.

The ability to love selflessly, to give without expectation and to guide without control, becomes the highest form of spiritual evolution. Eugene may never again hold Gaya in his arms, but his capacity to love Angel with sincerity and humility becomes the true culmination of his long journey.

The Desire to Be Understood

Throughout Again and Again, Eugene’s struggle is not only against time or mortality but against invisibility—the deep human need to be seen and believed. Whether interacting with Wayne, who represents rational skepticism, or recounting lifetimes to Angel, Eugene consistently faces the painful reality that his truth is too strange for most to accept.

The dismissals he encounters echo those from earlier lives where he was ignored, mistrusted, or dehumanized. Being labeled as delusional or senile in his final years is a final insult to a man who has witnessed entire eras pass.

This yearning to be understood is not about vanity or even vindication; it is about affirmation of existence. Eugene does not simply want someone to nod politely—he wants to be believed in a way that makes his experiences matter.

This desire is partially fulfilled in his growing relationship with Angel, whose own struggles with identity and worth make him more receptive to Eugene’s story. The empathy that grows between them allows Eugene, for perhaps the first time, to feel less alone.

It is not just the acceptance of his narrative that comforts him, but the fact that someone sees his pain, his hope, and his truth. The novel uses this theme to explore the broader idea of how marginalized voices—those who speak of the mystical, the traumatized, the emotionally complex—are often erased in modern culture.

Eugene’s arc becomes a meditation on the sacredness of being known. Even one act of genuine understanding can alter the trajectory of a life, or many lives.