Airplane Mode Summary, Analysis and Themes

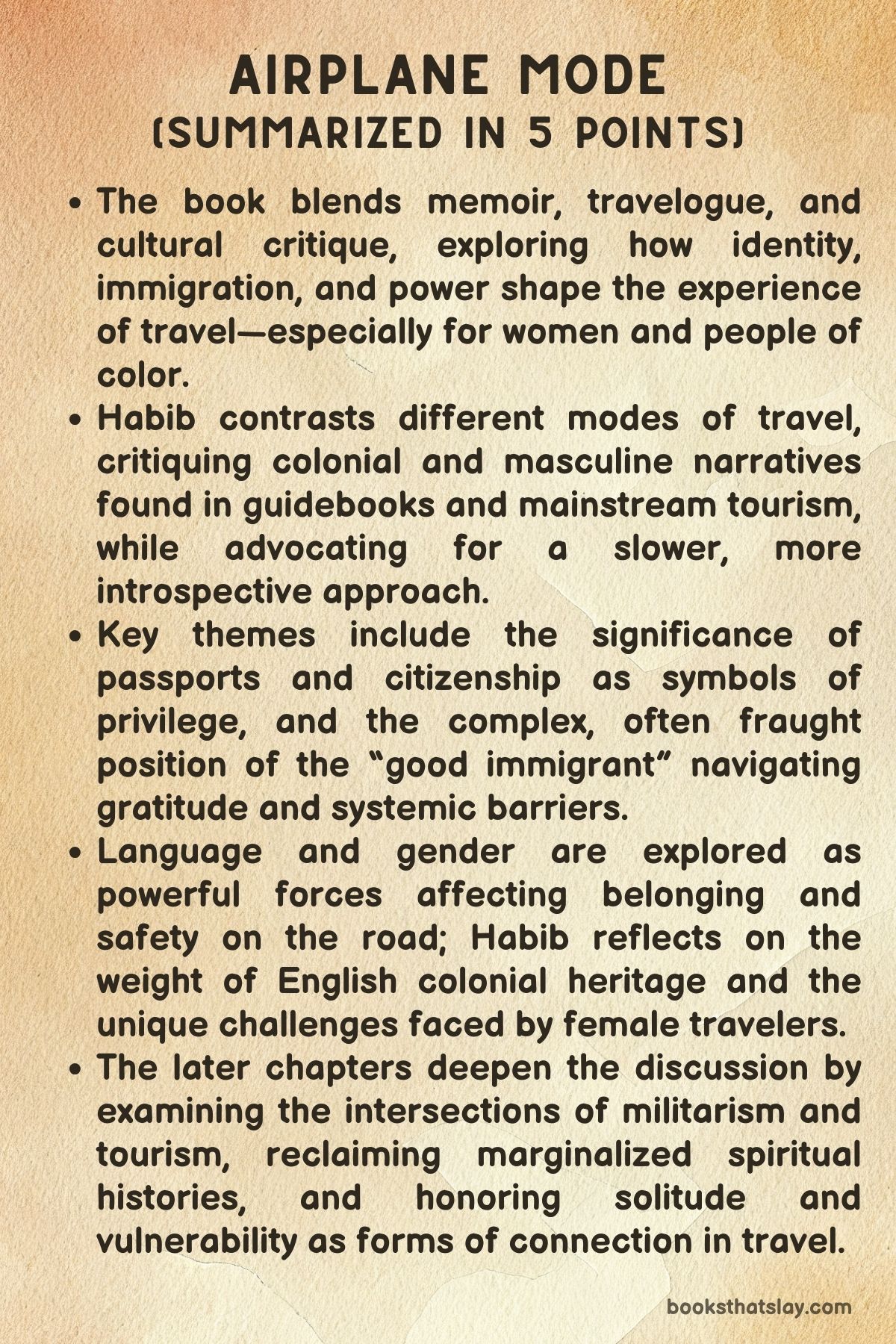

Airplane Mode by Shahnaz Habib is a striking blend of memoir, travelogue, and cultural critique.

It is written by Shahnaz Habib—a writer, translator, and immigrant who deftly explores what it means to move through the world when you don’t quite fit the image of the “default traveler.” Through nine beautiful chapters, Habib interrogates travel’s entanglement with race, gender, class, and postcolonial legacies. She reflects on her experiences as a brown, Muslim, immigrant woman traveling alone. The book traces how identity shapes—and is shaped by—mobility, documentation, and the stories we tell about journeys. With sharp intelligence and tender vulnerability, Habib invites readers to rethink what it means to belong, to wander, and to see.

Summary

Shahnaz Habib’s Airplane Mode opens not with a checklist of exotic destinations, but with a sense of uncertainty and contradiction. She describes her own experience as a brown, Muslim, immigrant woman who both longs to travel and feels out of place wherever she goes.

In Istanbul, she befriends Megan, a white backpacker, and is struck by how differently the world receives each of them. Habib’s travels are marked by constant self-surveillance and caution, in stark contrast to the carefree mobility associated with Western tourists.

This tension becomes the foundation for her deep, searching inquiry into the politics and psychology of travel. Early on, Habib revisits the first time she lost her passport in Japan, and what it meant to move from India to the United States.

The passport, for her, morphs from a piece of paper to a symbol heavy with meaning—of borders, belonging, and vulnerability. Becoming a U.S. citizen isn’t a simple upgrade; it means giving up her Indian citizenship, a wrenching bureaucratic and emotional shift.

Throughout, she traces how passports and visas serve as gatekeepers, enabling some to cross borders with ease and others only with risk or fear. The narrative shifts to Habib’s life as a new immigrant in America, where the myth of the “good immigrant” looms large.

She recounts the invisible labor, precarity, and expectation of gratitude that defines her early years—working low-wage jobs, navigating legal limbo, and feeling perpetually watched. Unlike privileged travelers who see migration as an adventure, Habib notes how immigrants rarely get to distinguish between migration and travel.

Movement is always fraught, survival, not leisure. Language, too, is an arena of power.

Habib reflects on her complicated relationship with English—a colonial legacy in her native Kerala that becomes both a ticket to literary ambition and a reminder of her outsider status. She meditates on code-switching, translation, and the deep desire to belong linguistically, much as she does physically.

Habib then turns to gender, examining the dangers and isolation that trail female travelers. She shares stories of street harassment and the ever-present tension between risk and freedom.

The book sharply critiques the romance of “finding oneself” through solo travel—a privilege rarely available to women, who are trained to be vigilant even as they’re told to seek adventure. Here, Habib’s voice is resolutely honest, acknowledging both the joys and exhaustion of traveling while female.

In the later chapters, Habib expands her focus to the links between tourism, militarism, and empire. In Turkey’s Konya, she observes how tourists, soldiers, and local guides occupy overlapping spaces—each enacting a different kind of power.

She critiques the way Western guidebooks shape narratives, often presenting the Global South as an exotic, consumable spectacle. Habib calls for more authentic, hybrid perspectives.

The book also takes on a spiritual and historical dimension as Habib seeks out the tomb of Tavuz Khatun, a semi-mythical Sufi figure who may have defied both gender and cultural boundaries. Her solitary pilgrimage becomes a moment of connection across time and difference, highlighting the power of marginalized stories and mysticism.

As the journey winds down, Habib reflects on solitude, prayer, and being an outsider—finding unexpected communion in sacred spaces and in the company of other women travelers, past and present. The narrative remains fiercely self-aware, always circling back to the question: Who gets to travel, who gets to tell the story, and what does it really mean to belong?

Airplane Mode ultimately refuses the easy triumphs of typical travel writing. Instead, it’s a meditation on movement that is as much about vulnerability as it is about discovery, centering those who are too often left at the margins of travel narratives.

Important People

Shahnaz Habib

Shahnaz Habib, the narrator and central figure of Airplane Mode, is both the traveler and the lens through which the entire book is experienced. She is a complex, introspective woman, shaped by her identity as an immigrant, a woman of color, and a writer.

Habib’s journey is not just geographical but existential. She is constantly negotiating her place between cultures, languages, and social expectations.

Her approach to travel is marked by vulnerability and honesty, often questioning the colonial, masculine norms that define conventional tourism. Throughout the book, she wrestles with loneliness, anxiety, and a persistent sense of otherness, both in foreign countries and in her adopted home of America.

Habib’s intelligence and self-awareness make her both a sharp critic and an empathetic observer, able to see herself as both subject and object of travel’s power dynamics. Her voice is reflective, skeptical of authority—whether it is embodied in passports, guidebooks, or cultural myths—yet also deeply open to spiritual and emotional transformation.

Megan

Megan, a white Western backpacker whom Habib encounters early in her travels, serves as a foil to Habib’s own tentative, self-questioning mode of travel. Megan represents a particular archetype: the bold, carefree, and often oblivious traveler for whom the world is a playground and who moves through it with inherited confidence.

Megan’s privilege, both racial and cultural, is evident in her lack of fear and her sense of entitlement to spaces and experiences that feel fraught and contested for Habib. While Megan is not a villain, her presence throws into relief the many layers of negotiation and caution that shape Habib’s travels.

Megan’s character thus acts less as an individual and more as an embodiment of the Western gaze and its unexamined freedoms.

The Parents

Habib’s parents, though largely present in memory and through her reflections rather than in real time, exert a significant influence on her understanding of travel, belonging, and identity. Her relationship with them is colored by the complexities of migration and cultural inheritance.

As loving yet cautious figures, they embody both the nostalgia and the anxieties of home, representing a world that is both lost and continuously recreated through Habib’s journeys. Her parents’ experiences of place, language, and adaptation are echoed in her own, forming a generational dialogue that underpins the memoir’s exploration of displacement.

The Immigrant Worker

The figure of the immigrant worker, though often presented collectively or through composite vignettes, is a crucial character in Habib’s narrative. Whether it is herself working minimum-wage jobs, or the anonymous laborers she encounters while traveling, this character stands in contrast to the myth of the carefree tourist.

The immigrant worker embodies vulnerability, resilience, and the necessity of movement for survival rather than pleasure. Through these figures, Habib interrogates who gets to move freely and who moves out of compulsion, revealing the labor, sacrifice, and bureaucratic hurdles that underpin most forms of modern travel for marginalized people.

The Gatekeepers

Guidebook authors, border officials, and bureaucrats appear throughout Airplane Mode as “gatekeepers,” wielding both literal and symbolic power over movement and belonging. These characters are often faceless or anonymous, but their impact on the narrator is profound.

Whether through the imposition of arbitrary rules, the shaping of narrative through travel literature, or the silent surveillance of immigration offices, the gatekeepers reinforce systems of privilege, exclusion, and control. Habib’s encounters with them are marked by frustration and skepticism, but also by an acute awareness of the historical and ongoing violences that shape global mobility.

Tavuz Khatun and the Sufi Figures

In the latter chapters, Habib’s journey brings her into contact with mythic and spiritual characters, most notably Tavuz Khatun, a possibly legendary Sufi saint. These figures are enveloped in ambiguity, gender fluidity, and the mysteries of faith.

Tavuz Khatun, who may have been an Indian woman traveling in disguise, becomes a symbol of the hidden, transgressive travelers of history—those who move not for conquest or commerce, but for love, devotion, or transformation. The dervishes and spiritual seekers Habib meets are both guides and gatekeepers of a different kind, inviting her to imagine new forms of belonging beyond national or gender boundaries.

The Women Travelers

Throughout the memoir, Habib invokes an imagined community of women travelers—both her contemporaries and those who came before her. These women, often unnamed or overlooked by history, appear as silent companions and sources of inspiration.

Habib honors their resilience, creativity, and the ways they have carved out space for themselves in a world not built for their freedom. Their presence in the text is less as individuals and more as an ancestral chorus, urging the narrator toward courage and self-acceptance.

Analysis and Themes

Decolonizing Travel

A fundamental theme of Airplane Mode is the dismantling of colonial frameworks that persistently shape how travel is imagined, experienced, and documented. Habib interrogates the inherited gaze embedded within traditional travel writing—exemplified by the Baedeker and Lonely Planet guidebooks—which historically positioned the white, Western, male traveler as the default narrator and arbiter of value.

In her journeys, Habib is constantly aware of how her own presence is mediated through these established templates, which cast the Global South as a site for Western consumption, exoticism, and adventure. By deliberately slowing down, foregrounding subjective experience, and resisting the pressure to “collect” places as achievements, she seeks to unravel this imperial legacy and invent a new travel ethos.

This ethos is more accountable, self-aware, and open to the ambiguous realities of postcolonial identities. Through this process, Habib advocates for a radical reorientation of travel: away from conquest and cataloguing, toward an ethic of listening, vulnerability, and mutual transformation.

Bureaucratic Intimacies of Citizenship, Borders, and the Politics of the Passport

Habib’s narrative is haunted by the shifting power of documentation—most notably, the passport—as both a bureaucratic tool and a deeply personal artifact. Her evolving relationship with her own passport, from a casual booklet to a heavily weighted symbol of privilege and loss, dramatizes the painful trade-offs of migration and naturalization.

The act of renouncing Indian citizenship and acquiring American nationality is not just an administrative shift, but a rupture that severs and remakes the self at multiple levels.

Habib connects her story to a broader politics of borders, where travel is never just a question of movement, but a fraught negotiation with state surveillance, institutional suspicion, and ever-present vulnerability for those who are not globally privileged.

Her reflections reveal how the freedom to travel—often romanticized in Western narratives—is in fact a highly uneven and contingent right, subject to the whims of political regimes and the accidents of birth. In this theme, travel itself is exposed as a privilege denied to many, and the passport becomes an emblem of the world’s deep inequalities.

Risk, Resilience, and the Mythology of Female Freedom

Another major theme in Airplane Mode is the negotiation of physical and psychological space by women travelers, as Habib scrutinizes the gendered realities that structure the experience of movement. The book candidly examines the double-bind faced by women on the road: while travel is supposed to be a journey toward freedom, self-discovery, and adventure, it is simultaneously shadowed by threat, scrutiny, and the imperative to remain hyper-vigilant.

Habib interrogates both the external dangers—harassment, violence, and societal policing—and the internalized burdens that come with occupying space as a woman.

Yet, instead of succumbing to victimhood or valorizing simplistic empowerment, she explores how solitude, caution, and even fear can become sites of creativity, resistance, and strength.

By sharing the ordinary acts of courage required in “traveling while female,” Habib destabilizes romanticized narratives. She claims a more complex, embodied agency for women who move through the world on their own terms.

Linguistic Belonging and the Afterlife of Empire

Language emerges in Habib’s work not simply as a tool for communication, but as a deeply fraught inheritance tied to colonial history and personal aspiration. Growing up in Kerala amidst the lingering ghosts of the British Empire, Habib’s relationship with English is ambivalent: it is at once a pathway to cosmopolitan mobility and literary expression, and a reminder of dispossession, exclusion, and longing.

The act of writing—and traveling—in English thus becomes a metaphor for navigating borderlands of identity, always negotiating between translation, code-switching, and the desire for genuine belonging. Habib’s linguistic journey mirrors her physical travel, as both are shaped by questions of power, legitimacy, and desire.

Ultimately, her use of English is neither a simple act of assimilation nor resistance, but a complicated process of reclaiming agency within the ongoing aftermath of empire.

Militourism and the Entanglement of Travel with Violence, War, and Narrative Control

One of the most original themes in Airplane Mode is Habib’s exploration of “militourism”—the way tourism and militarism intersect, often invisibly, in shaping who can travel, where, and under what circumstances.

Through her observations in places like Konya and Gallipoli, she exposes how the paths of tourists are frequently carved out by the lingering presence of armies, wars, and geopolitical interests.

Soldiers buying carpets, tourists visiting battlefields, and the infrastructure that connects these spheres reveal the extent to which violence underpins the apparent innocence of travel.

Habib’s analysis complicates the idea of tourism as a harmless leisure activity, arguing that it often perpetuates imperial power structures and narratives, especially in postcolonial landscapes.

She urges readers to recognize these hidden connections and question the ethical implications of their own mobility.

Spiritual Wayfaring

In its later chapters, the book takes on an almost mystical dimension, as Habib’s travels become quests for meaning beyond the physical journey. Her search for the tomb of Tavuz Khatun and her participation in secretive Sufi ceremonies reflect a longing for spiritual connection that transcends conventional religious boundaries.

These experiences are filtered through the lens of gender and marginality, as Habib finds herself drawn to figures and spaces that defy official histories—whether it’s a possibly legendary Sufi woman or a modest hilltop mosque. Spiritual seeking becomes an act of feminist reclamation, as Habib honors forgotten or overlooked stories, embraces vulnerability as sacred, and frames solitude itself as a form of prayer.

In this sense, the book’s journey is not toward mastery or possession, but toward deeper humility, gratitude, and the recognition of shared humanity across difference.

Hybridity, Inauthenticity, and the Ethics of Storytelling in an Age of Global Tourism

Finally, Airplane Mode offers a critical meditation on the idea of authenticity—both in travel and in storytelling. Habib resists the fetishization of the “authentic” that pervades tourist marketing and mainstream travel narratives, recognizing that cultures, people, and places are always in flux, shaped by migration, hybridity, and contradiction.

She points to the importance of making space for messy, imperfect stories—ones that acknowledge inauthenticity as not a failure, but a more honest reflection of the complexities of the modern world.

Through this embrace of hybridity, Habib calls for a more ethical form of travel writing: one that centers humility, amplifies marginalized voices, and refuses the easy satisfactions of consumption and spectacle.