American Bulk by Emily Mester Summary and Analysis

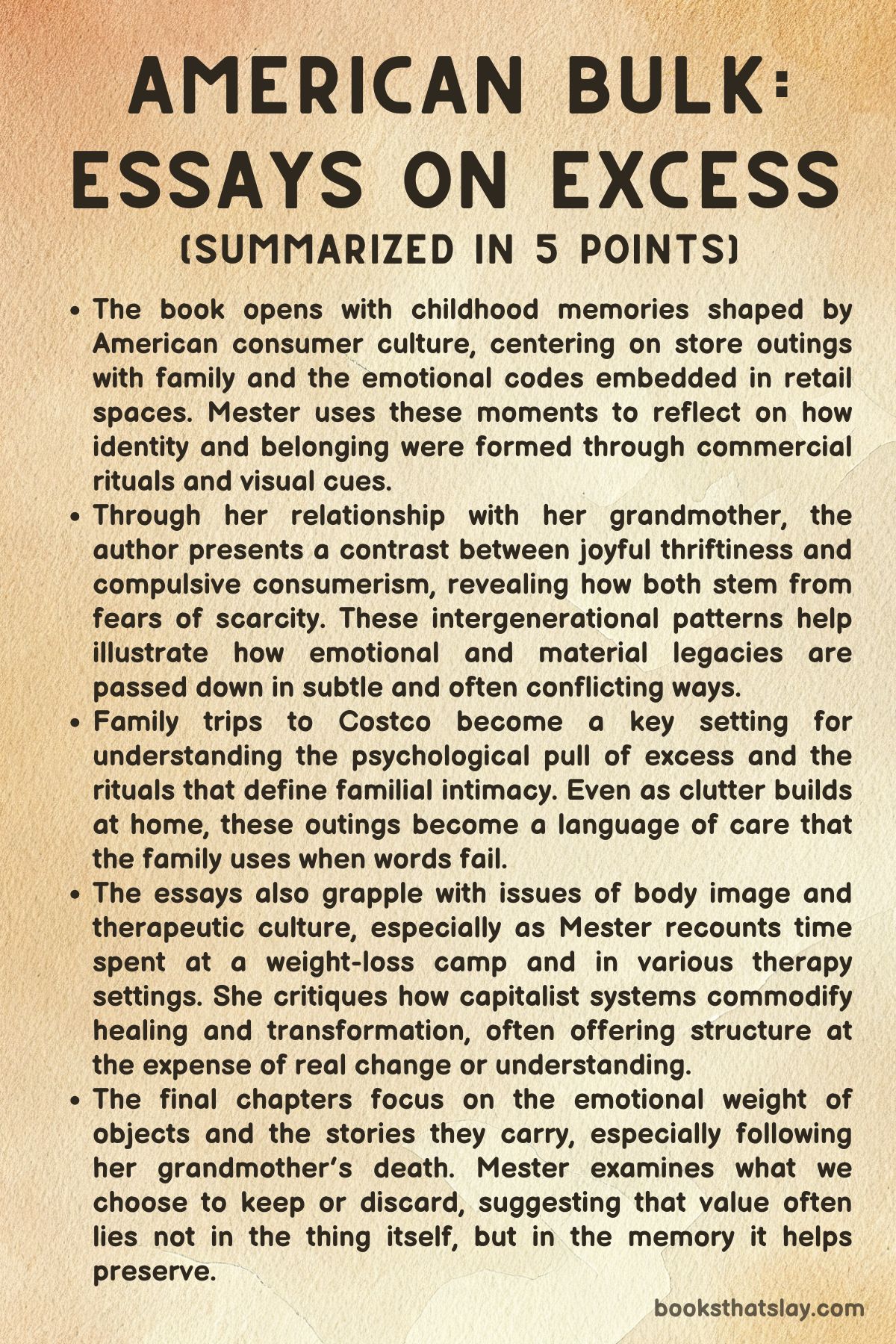

American Bulk by Emily Mester is a striking, often heartbreaking, and sharply intelligent collection of personal essays that reflect on consumerism, body politics, class anxiety, and familial inheritance in modern America. Rather than offering straightforward memoir or cultural criticism, Mester blends the two—her personal history of growing up with a compulsive-shopping father and a frugal grandmother becomes a lens through which broader systems of consumption, scarcity, and identity are explored.

Her prose is intimate yet analytically rich, frequently moving between nostalgia, satire, and sorrow. At its heart, the book is a meditation on the emotional and psychological residue of living in a country where the desire for more—more stuff, less body, more control—is never quite fulfilled.

Summary

Emily Mester’s American Bulk opens with memories of her childhood shaped by the rhythms of suburban shopping. In the “Introduction,” she recalls how store signs and family rituals of consumption became her first language—learning to read not through books but through branding.

Her home, filled with unopened purchases, becomes an emblem of affection and identity formed in the aisles of big-box retailers. Her father’s tendency to leave bags on the dining table, a space meant for holidays, stands as a symbol for both bounty and disarray.

Consumption wasn’t just a habit—it was a familial script she internalized early. In the first installment of the recurring “Storm Lake” essays, Mester introduces her grandmother, a woman who collected brochures and free goods with purpose and pride.

Visits to Storm Lake, Iowa, are colored by the warmth of that relationship, though marred by her grandmother’s reluctance to reveal the full truth of her cluttered, shame-filled life. These chapters trace how class, memory, and identity are passed down not only through genetics but through the emotional undercurrents of how and why we keep things.

In “Wholesale,” Mester positions Costco as a sacred space of abundance, where her father’s compulsive shopping takes on ritualistic meaning. She contrasts his acquisitive behavior with her grandmother’s thriftiness, showing how both were driven by the same desire: to possess against the threat of future loss.

Costco becomes a backdrop for family bonding, where shared silence and overflowing carts act as a substitute for spoken love. “Al Forno” turns the focus to food and class as Mester grapples with the contradictions of loving mall-chain restaurants like Olive Garden while trying to assimilate into the elite culture of a New England prep school.

The essay critiques both WASP taste and hipster aesthetic for their covert systems of judgment. Her father’s unashamed palate stands in opposition to her own insecurity, embodying a freedom she can’t quite claim.

Food, once a source of comfort, becomes a symbol of cultural tension. “Live, Laugh, Lose” recounts her experience at a fat camp, where control and structure paradoxically offer a reprieve from shame.

She finds comfort in routine, absence of temptation, and a communal space where other girls carry the same bodily burdens. The camp becomes a strange haven where solidarity thrives under systems of weight loss.

In contrast to mainstream narratives of cruelty, Mester presents the camp as a site of relative freedom and belonging. Returning to her grandmother in “Storm Lake, Part 2,” Mester examines how aging and mental decline blur the lines between collecting and hoarding.

Her grandmother’s condo becomes a dense archive of sentiment, cluttered with items that cannot be parted with because of the emotions they carry. This triggers a reflection on Mester’s own tendencies and the broader human desire to preserve memory through objects.

In “Shrink,” the focus shifts to therapy, where Mester critiques the commodification of mental health. Finding the right therapist begins to resemble product hunting—fit, branding, emotional ROI.

She laments how therapy often becomes another space of managed performance, where insight doesn’t always lead to change. “Testimonial” centers on her brief stint as the face of a diet company, where her weight loss is commodified and her image becomes a marketing tool.

She interrogates the narrative arc of redemption embedded in weight loss stories, recognizing that transformation is often shallow and short-lived. The testimonial becomes both confession and performance, driven by a culture obsessed with thinness and discipline.

In “While Supplies Last,” Mester unpacks the artificial scarcity manufactured by capitalism. Flash sales and discount bins echo broader cultural urgencies—get love, get thin, get success before it’s gone.

The constant call to act fast creates a state of anxious living. This anxiety returns in “Storm Lake, Part 3,” where Mester and her father sift through her late grandmother’s belongings, struggling to discern what to keep and what to let go.

Objects transform into emotional artifacts, and grief resists neat resolution. Through all ten chapters, American Bulk builds a mosaic of American life marked by longing, accumulation, and the ache of what’s missing even in abundance.

Key People

Emily Mester (Narrator and Protagonist)

Emily Mester presents herself as both the observer and the observed, a self-aware narrator who uses memoir as a mirror for cultural critique. She is complex, often conflicted, and deeply reflective.

Her identity is shaped by the contradictions of American consumer culture, body image, class anxiety, and familial attachment. From early childhood, she is steeped in the visual and emotional language of consumerism, absorbing its codes like scripture.

Yet, she is never just a passive product of her environment. Mester is constantly interrogating the structures that shape her: the rituals of Costco, the norms of elite boarding schools, the commodification of therapy, the emotional labor of weight-loss testimonials.

She is attuned to how excess—whether material, emotional, or bodily—both nurtures and suffocates her. Her character is at once tender and analytical, oscillating between humor and vulnerability.

Her journey across the essays traces not a linear arc of growth, but a spiral of returns to shame, nostalgia, and desire. She is always looking for meaning in the mess.

Mester’s Father

The father is a vivid emblem of consumerist excess, yet he is never caricatured. He is a man who expresses love through accumulation.

His compulsive shopping habits—particularly in bulk at Costco—are less about utility and more about symbolic wealth, emotional abundance, and the fear of not having enough. He buys items he never uses, lets clutter fill their home, and resists the aspirational values of elite culture.

His vulgarity and consumer appetites are both a rejection of social pretension and a source of tension in the family. But he is also deeply affectionate in his own way, especially during shopping trips when he becomes unusually generous and carefree.

In later chapters, especially in the posthumous sorting of the grandmother’s belongings, his emotional depth emerges through his unspoken grief and reverence for memory. His character encapsulates a kind of American masculinity tethered to consumption, but also to love expressed through material provision rather than words.

Mester’s Grandmother

The grandmother is a poignant counterpoint to the father, embodying a different kind of excess: that of sentimental hoarding rather than acquisitive consumption. She collects not to display wealth, but to preserve meaning.

She hoards brochures, business cards, and old teaching supplies—not for show, but because they contain remnants of life and identity. Mester’s connection to her grandmother is intimate and haunted by unfulfilled knowing.

Her grandmother’s reluctance to show her the cluttered Storm Lake house or to openly discuss her inner life conveys a sense of shame that runs beneath their shared history. As she ages and descends into dementia, her hoarding takes on a tragic texture, a visible metaphor for the erosion of selfhood.

Yet, Mester ultimately reframes her clutter as an act of emotional archiving—an attempt to resist erasure and to hold on to a life that mattered. The grandmother’s character becomes a quiet center of the book’s meditation on memory, legacy, and the intimate cost of material things.

Mester’s Mother

The mother is less central but offers a sharp contrast to both father and daughter. She is disciplined, moderate, and emotionally restrained, particularly around food and consumption.

Her farewell dinner at the Olive Garden, before Mester departs for fat camp, reveals her role as a kind of moral compass—unmoved by indulgence, quietly judgmental, and emotionally guarded. While not cold, she seems detached from the larger dramas of excess that preoccupy other characters.

Her intuitive moderation stands in contrast to Mester’s appetites, creating a dynamic of both admiration and alienation. The mother appears as a foil to Mester’s struggles, representing a kind of stoicism that Mester cannot adopt and perhaps resents.

Camp Pocono Trails Bunkmates

Though unnamed and briefly sketched, the girls Mester meets at fat camp form a crucial emotional community in her narrative. They are fellow travelers in the struggle for bodily acceptance, each carrying their own burdens of shame and desire.

Mester portrays them with affection and empathy, highlighting the silent solidarity that arises among them in a space where fatness is both normalized and pathologized. They are not just backdrops to her story but co-authors of a collective experience.

This experience challenges the mainstream narrative of fat camps as unilaterally traumatic. Their presence gives shape to Mester’s evolving understanding of hunger—not just for food, but for recognition, connection, and freedom.

The Therapist

The therapist in “Shrink” is a figure of clinical detachment and institutional failure. She represents the impersonal, commodified version of mental healthcare that Mester critiques.

She is a practitioner fluent in the language of boundaries and reframing but disconnected from emotional nuance. Mester’s interactions with her are marked by frustration, as she feels unseen and misunderstood.

This character becomes a stand-in for a broader critique of therapy in neoliberal culture. In this world, healing is monetized and emotional labor is bureaucratized.

The therapist isn’t malicious, but her clinical rigidity reveals the limits of a system that privileges technique over intimacy.

Emily’s SlimGenics Persona

This version of Mester—posed, performative, and scripted—emerges in “Testimonial” as a fragmented character in her own right. She is the “After” photo in a commercial, a public-facing avatar of transformation meant to sell a product.

This persona is less a mask and more a cultural artifact—a version of the self designed to be consumed. Mester’s reflections on this period reveal the hollowness beneath the surface.

Despite weight loss and applause, hunger persists. Her testimonial self is a mirror to society’s obsession with visible success and the moral arc of weight loss.

As a character, this version of Emily embodies the tension between appearance and authenticity, self-erasure and self-creation.

Analysis of Themes

Consumerism as Emotional Infrastructure

Emily Mester presents consumerism not just as a cultural force, but as the bedrock of emotional life and familial connection. The essay collection is haunted by the logic of acquisition—not only as a way of getting things, but as a structure through which love, memory, and identity are mediated.

The retail landscape becomes the geography of her childhood. Stores, products, and routines aren’t trivial—they are sacred, encoded with feeling.

Costco visits serve as a rare moment of family unity. The accumulation of khakis and gadgets reflects a father’s emotional vocabulary, a way to provide when words might have failed.

Consumer objects—mass-produced, disposable, garish—become relics of relationship. Mester suggests that for many working- or middle-class American families, especially those shaped by financial precarity or aspirational striving, the language of retail can often feel more tangible than the abstract vocabulary of intimacy.

Her grandmother’s obsessive collection of free items reflects a similar logic. The free brochure is not just a thing but a gesture, a declaration of existence.

Mester resists easy condemnation of consumerism. She doesn’t romanticize it, but she understands its emotional gravity.

The act of purchasing or hoarding becomes a way of managing anxiety, recording care, and confronting scarcity. In this light, the excess isn’t just about stuff—it’s about everything we fear we won’t have enough of: love, time, safety, memory.

American bulk, then, is not just about volume but about value. It captures the desperate attempt to make love visible and legacy material.

Inheritance, Memory, and Material Legacy

A central theme coursing through Mester’s essays is the way inheritance functions not just through genetics or money, but through objects, habits, and emotional residue. She returns repeatedly to her grandmother—first as a lively figure thrilled by free things, then as a fading presence buried under her own belongings.

Mester examines the slow erosion of dignity and memory that aging brings. This is particularly poignant in a culture where meaning is so often tied to order and productivity.

As her grandmother deteriorates, her hoarding becomes less joyful and more desperate. It becomes a silent protest against disappearance.

But Mester resists the clinical impulse to pathologize this behavior. Instead, she treats it as a kind of memorial-making, a futile but noble effort to preserve a self no longer recognized in the mirror.

Her essays suggest that what we leave behind often isn’t coherent—it’s messy, contradictory, and charged with private meaning. Children and grandchildren are left to make sense of this emotional detritus.

They sift through boxes that are equal parts trash and treasure. This search becomes a meditation on legacy.

How do we want to be remembered? What parts of us survive through the things we leave behind?

The act of sorting becomes a form of grieving, but also of interpreting. Mester shows that even the most mundane object—a broken chair, a discarded coupon—can become a vessel of narrative.

Through this lens, inheritance isn’t just about what is given. It’s about what is remembered, misunderstood, or mourned.

Shame, Body, and the Desire to Disappear

Across several essays, Mester explores how shame—especially around the body—becomes internalized through social institutions like family, school, therapy, and even retail. The theme of weight recurs with urgency.

From her time at “fat camp” to her testimonial for SlimGenics, Mester examines how the body becomes a site of discipline, surveillance, and projection. These experiences are not framed as isolated incidents.

They are presented as nodes in a cultural script that equates thinness with virtue and excess with failure. Control—over hunger, emotion, self-presentation—becomes aspirational.

At Camp Pocono Trails, Mester paradoxically finds freedom in regimentation. The structured meals and fixed routines eliminate choice, and thus guilt.

This liberation is bittersweet. It highlights how profoundly shame shapes behavior.

Her weight-loss testimonial becomes another performance of conformity. It is a transaction in which personal pain is repackaged as triumph.

Even in moments of supposed transformation, Mester admits to a lingering hunger. This hunger is not just for food, but for security, love, and stability.

The body, in her view, becomes a metaphor for unfulfilled need. In critiquing the culture of shrinkage, Mester implicates both corporate diet culture and a broader neoliberal ideology.

This ideology conflates self-worth with marketable progress. The desire to disappear, to be small, to control the mess—whether bodily or emotional—is not personal pathology but social expectation.

Mester ultimately questions whether any “after” can satisfy in a culture that constantly moves the goalpost. She offers instead a raw honesty about the uneasy truce many live with in their own skin.

Class, Taste, and the Performance of Belonging

Emily Mester’s essays are finely attuned to the social nuances of taste as a marker of class. She reflects on the dissonance between her Midwestern, middle-class upbringing and her later exposure to elite academic and cultural spaces.

Restaurants like the Olive Garden or retail rituals like shopping at TJ Maxx are not treated as punchlines. They are rich sites of belonging, pleasure, and nostalgia.

Once Mester enters spaces dominated by upper-class sensibilities, she becomes acutely aware of the performative dimensions of taste. Both WASP culture and hipster aesthetics operate through codes of authenticity and disdain.

These cultural modes often target the very pleasures she grew up cherishing. This generates a lifelong internal tension.

How does one hold onto what they genuinely love while recognizing the social cost of loving it? Mester’s father, in contrast, represents unapologetic vulgarity.

He enjoys things without needing approval. His confident declaration, “I like this,” becomes a quiet act of resistance against elitism.

Mester finds herself caught between desire and embarrassment. She feels the pull of both loyalty and aspiration.

This theme resonates in a society where class mobility is often accompanied by cultural alienation. Through her exploration of taste, Mester shows that class is not just about income.

It is about fluency—knowing what to wear, where to eat, and how to speak. Her essays dissect how taste becomes a script.

Deviation from it invites scrutiny or shame. Yet she also reveals the emotional cost of assimilation and the quiet bravery of those who refuse to apologize for their pleasures.

Therapy, Self-Help, and the Commodification of Healing

Another vital theme in Mester’s work is the uneasy relationship between therapy and capitalism. In her essay “Shrink,” she shows how mental health treatment can mirror the same consumerist logic it claims to oppose.

Therapy becomes a marketplace. Clients shop for providers, evaluate “fit,” and absorb therapeutic language like branded content.

Mester recalls sessions where buzzwords replace real engagement. Words like “boundaries” and “coping skills” become placeholders rather than paths.

She doesn’t dismiss therapy’s value. But she critiques its assimilation into a system that prioritizes productivity and perpetual self-improvement.

The therapeutic encounter often feels like maintenance. It becomes a way to keep going in a system that remains unchallenged.

Wellness becomes another consumer choice. It is another subscription service or algorithmic recommendation.

This framing flattens suffering. Instead of systemic critique, patients are given coping strategies.

Instead of community or change, they get affirmations and apps. Mester mourns this lost potential.

She imagines a therapeutic space that resists commodification. One that embraces context and complexity.

Her treatment of therapy is not cynical. It is cautionary.

She longs for a space where pain can be named without being monetized. Where help is not wrapped in branding or jargon.