An Age of Winters Summary, Characters and Themes

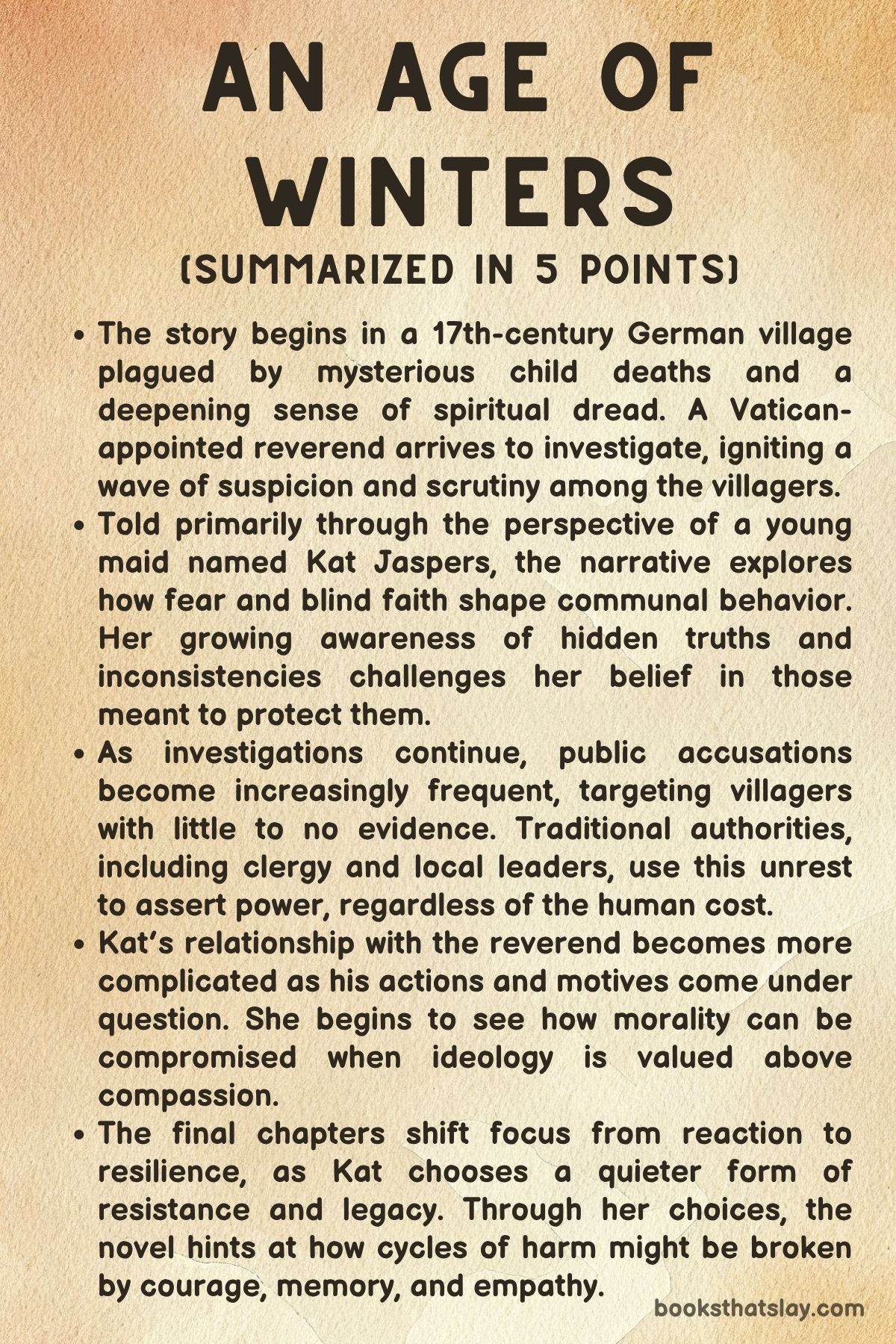

An Age of Winters by Gemma Liviero is a chilling and psychologically dense historical novel that explores the dark undercurrents of power, superstition, and moral decay in a 17th-century European village. Set against the bitter backdrop of an unrelenting winter in Eisbach, the story opens with the disturbing discovery of murdered children and unfolds into a broader tale of community hysteria, religious persecution, and psychological manipulation.

Told primarily through the eyes of Katarin Jaspers, a maidservant with hidden depths, and Reverend Zacharias Engel, a mysterious clergyman with secrets of his own, the novel steadily peels away layers of deceit and horror. Liviero’s narrative delivers a haunting commentary on justice, patriarchy, and the devastating cost of collective fear.

Summary

The novel begins in the village of Eisbach, where the harsh onset of winter coincides with a series of child murders. First, the bruised body of young Hermann Kropp is pulled from the frozen river, the third in a string of killings that includes a slaughtered infant and a four-year-old girl named Lottie, laid carefully in the woods with her throat slit.

The contrast between the brutal method and the tender placement of Lottie’s body hints at a conflicted killer—one who swings between malice and regret.

Reverend Felix Stern, an aging, ailing priest, is burdened with providing spiritual guidance to a traumatized community. He is skeptical of the wave of superstitious paranoia gripping the villagers and cautions against rash accusations.

Despite his warnings, mass hysteria overtakes reason. Fourteen villagers are arrested, including Freya Pappenheimer, accused by her husband of witchcraft after using a fertility potion.

Her confession to this minor act and subsequent suicide in jail bring no closure. Stern believes the real perpetrator remains free and becomes increasingly disillusioned with the Church’s heavy-handed tactics.

Ultimately, he dies without naming a successor, and the ecclesiastical authorities send a young priest, Reverend Zacharias Engel, to replace him.

Engel arrives with a scholarly mind and a commanding presence. He quickly impresses the villagers and unsettles them with his probing demeanor.

Among those most affected is Katarin Jaspers, a servant at the clergy house. She is captivated by Engel’s intellect and power, yet remains wary of his intentions.

As Engel begins interrogations under the guise of divine duty, rumors swirl, and fear festers. His investigation leads him to the imprisoned Leon von Kleist, a once-respected judge now accused of murdering his family and consorting with the Devil.

Kleist, held in medieval squalor, proclaims his innocence. He insists his family died of illness and that his behavior—such as dancing with his daughter—was misread by those seeking a scapegoat.

Despite Engel’s initial doubt, mounting pressure from Commissioner Ehrenberg leads him to endorse a confession extracted through torture. Kleist, shattered and broken, confesses to all charges and is executed in a public spectacle meant to pacify the masses.

The villagers celebrate, believing justice has been served, but Engel remains unmoved, and Katarin’s suspicions grow.

After the execution, the village enters a brief lull. Engel becomes both revered and feared, while Katarin continues to wrestle with her ambiguous feelings toward him.

When a disfigured child’s corpse is found bearing strange markings, the village is once again plunged into fear. Katarin, wary of Margaretha Katz, a newcomer midwife rumored to practice witchcraft, follows her into the woods.

There, she finds a missing child alive, earning praise from Engel and temporarily elevating her status. Still, doubts linger.

Engel’s praise is cold and calculated, and Katarin’s fascination with him borders on obsession.

As the story unfolds, Katarin becomes embroiled in deeper, darker events. She negotiates for an abortive potion on behalf of a desperate woman, Ursula, who later miscarriages and publicly displays her dead child in a moment of madness.

Engel begins to show internal conflict—he expresses concern over false confessions and admits to the burden of hearing horrific truths—but he remains complicit in the church’s operations.

Zilla Lucke, a woman known for her coarse manner but strong maternal instinct, becomes the next target. Her mentally impaired son, Jon, is left helpless as Zilla is arrested on charges of witchcraft.

False testimonies from neighbors Maude and Claudine Meyer, who seek to claim her property, seal her fate. Engel and Katarin visit Jon and see firsthand his heartbreaking state.

Yet Engel does not intervene. Zilla’s imprisonment is harsh, but she maintains her innocence and pleads for Jon’s safety.

Engel listens but allows the injustice to unfold, paralyzed by the system he serves.

Meanwhile, Ursula unravels completely, attacking Katarin and later murdering her mother-in-law. Engel escorts her to the city, where she is destined for a grim end.

The community, rotted by suspicion and desperation, continues to turn on itself.

Gradually, the narrative centers more fully on Katarin, revealing a sinister truth: she is the murderer. Despite initial appearances as a victim of abuse and circumstance, Katarin is shown to be a cunning manipulator, capable of orchestrating murders with precision and cruelty.

Her crimes include poisoning, smothering, and framing others—driven by trauma, desire, and a relentless hunger for control. Her obsession with Engel, her jealousy of Margaretha, and her willingness to use others like Walter all paint a chilling portrait of her descent.

Margaretha, believed to have died in a fire, resurfaces with Engel—who is revealed to be an imposter, a conman who assumed a dead priest’s identity. Together, they expose Katarin through a trap, and Walter—once her loyal companion—abandons her.

Even so, Katarin outmaneuvers justice once again. Pregnant, she is spared and flees into the wilderness.

She gives birth alone, abandons her child, and reinvents herself.

The novel ends with Katarin married to a wealthy doctor in Alsace, mother to a new child, and comfortably entrenched in a new identity. When she hears that Eisbach has been burned down by the prince-bishop, her smile suggests satisfaction, even triumph.

She has escaped all consequences and now lives free, her true nature masked behind charm and status.

An Age of Winters concludes on a haunting note. Katarin, the ultimate antiheroine, survives by weaponizing empathy, trauma, and deceit.

The novel condemns the ease with which societies destroy their most vulnerable, the complicity of institutions, and the terrifying potential of a mind unchecked by conscience. Her story is not one of redemption, but of quiet domination—the unsettling legacy of a survivor who leaves ruin in her wake.

Characters

Katarin Jaspers

Katarin Jaspers is the dark and complex protagonist of An Age of Winters by Gemma Liviero, a character whose arc shifts from sympathetic victim to terrifying antiheroine. Introduced as a lowly maidservant in a village plagued by superstition and murder, Katarin initially appears to be a shrewd observer navigating the oppressive confines of a deeply patriarchal and fearful society.

Her early actions—assisting a desperate woman in procuring an abortive potion or acting with compassion toward the orphan Walter—paint her as both brave and resourceful. Yet, beneath this veneer lies a mind steeped in trauma and driven by a chilling determination to survive, dominate, and reinvent herself.

Her intelligence is cloaked in subservience, allowing her to manipulate others with astonishing precision. As the narrative unfolds, her quiet cunning morphs into overt malice.

She is revealed to be the orchestrator of numerous murders, including the deaths of children, rivals, and those who threatened her ambitions. Even her romantic obsessions—first with Engel and later with Sigi—are filtered through a lens of manipulation and control.

Katarin is both victim and villain, molded by abuse yet fully autonomous in her cruelty. Her final reinvention as a doctor’s wife, wealthy and admired, underscores the disturbing success of her deceitful and violent ascent, leaving readers unsettled by her capacity to survive unpunished and unchanged.

Reverend Zacharias Engel

Reverend Zacharias Engel is a central figure in An Age of Winters, initially cast as a righteous inquisitor tasked with rooting out evil from the village of Eisbach. Presented as a theological and legal expert, Engel arrives with quiet authority and an enigmatic charm, quickly unsettling the villagers.

His stoicism and sharp intellect suggest moral clarity, but as the story progresses, a more conflicted and troubling figure emerges. Engel is deeply aware of the human cost of his work.

His private confessions to Katarin about innocent people being executed and the strain of harboring others’ confessions reveal a tormented man whose conscience is in tension with his clerical duties. Despite this, he continues to enforce the church’s will, even sanctioning the execution of Leon von Kleist under duress and turning a blind eye to the political machinations behind many accusations.

Ultimately, Engel himself is a fraud—an imposter who has assumed the identity of a dead clergyman for power and gain. Yet even this revelation does not entirely erase his earlier complexity; he is as much a survivor of a brutal system as he is a participant.

His ambiguous morality, hidden past, and capacity for both cruelty and care render him a compelling foil to Katarin, embodying the story’s themes of power, deception, and complicity.

Leon von Kleist

Leon von Kleist serves as one of the most tragic figures in An Age of Winters. A former judge and landowner, he is introduced while imprisoned under horrific conditions, awaiting execution for witchcraft and the murder of his family.

His story is a study in dignity eroded by institutional cruelty. Despite claiming innocence and attributing the deaths in his household to illness and betrayal, Leon is steadily broken by interrogation and torture.

His eventual coerced confession—detailing a pact with the Devil and other fabricated sins—exemplifies the novel’s critique of forced morality and show trials. Leon is a man caught in the machinery of political greed, particularly the ambitions of Prince-Bishop Ehrenberg, who covets his land.

His descent from respected patriarch to a broken, publicly executed pariah illustrates the devastating power of mass hysteria and institutional corruption. Even in his final moments, Leon clings to fragments of integrity, making his demise both horrifying and poignant.

Freya Pappenheimer

Freya Pappenheimer’s role in An Age of Winters is brief yet impactful, symbolizing how suspicion and misogyny intersect to destroy the innocent. Freya is accused by her own husband of witchcraft, her crime being the use of a fertility potion in hopes of bearing a child.

This act, intended to bring life, is twisted into evidence of her connection to death and diabolism. Her arrest and forced confession reflect the cruel logic of the witch hunts, where women’s bodies and choices are policed and punished.

Freya’s suicide in prison, following a heartfelt letter expressing grief and faith, underscores the emotional toll of religious and communal condemnation. Her death is not only tragic but emblematic of the wider devastation wrought by the village’s descent into paranoia.

Zilla Lucke

Zilla Lucke emerges as a defiant and resilient woman who, despite her coarse exterior, is a devoted mother to her intellectually impaired son, Jon. In An Age of Winters, Zilla becomes a victim of greed and societal malice when neighbors falsely accuse her of witchcraft to gain her land.

Her arrest is violent and dehumanizing, yet she never abandons her dignity. Her pleas to protect Jon are ignored by those more interested in her downfall than the truth.

Zilla represents the many women condemned not for crimes but for their poverty, independence, and perceived deviation from social norms. Her courage in the face of injustice and her ultimate sacrifice mark her as one of the narrative’s most poignant victims.

Margaretha Katz

Margaretha Katz, the mysterious healer and midwife, is a character cloaked in ambiguity throughout much of An Age of Winters. Feared and revered, she is suspected of witchcraft yet proves to be far more benevolent and perceptive than the villagers believe.

Margaretha operates outside the bounds of conventional medicine and morality, providing care and abortive remedies to women who have nowhere else to turn. Her survival of Katarin’s poisoning and her role in the final confrontation reveal her inner strength and cunning.

Together with Engel—who is revealed to be her husband—she helps expose Katarin’s true nature. Margaretha ultimately symbolizes a different kind of power: one rooted in knowledge, resilience, and empathy, rather than fear or deception.

Walter

Walter, the young orphan boy in An Age of Winters, offers a poignant contrast to the darkness that surrounds him. Innocent, trusting, and emotionally tethered to Katarin, he initially functions as a source of light and purity in the story.

As events unfold, Walter’s loyalty is tested and eventually shattered when he uncovers Katarin’s true, murderous nature. His transformation from a devoted companion to an agent of revelation is both heartbreaking and necessary.

Walter’s decision to align with Margaretha and Engel in unmasking Katarin marks his maturation and moral clarity, even in the face of betrayal. In a world rife with deception, Walter remains one of the few characters guided by a genuine sense of right and wrong.

Ursula Döhler

Ursula Döhler is a tragic figure whose descent into madness is emblematic of the collateral damage inflicted by a society gripped by fear and misogyny. Initially introduced as a desperate woman seeking an abortive potion to escape the cycle of poverty, Ursula’s life spirals into grief and violence after the death of her child.

Her public mourning, erratic behavior, and eventual murder of her mother-in-law reveal a woman unmoored by trauma. Ursula is both a victim and a cautionary tale—her mental collapse exploited and dismissed by those around her.

Her fate, sealed when Engel escorts her to the city, is a sobering reminder of how easily women are discarded once they no longer fit the roles imposed upon them.

Prince-Bishop Ehrenberg

Prince-Bishop Ehrenberg is the invisible hand behind much of the systemic cruelty in An Age of Winters. Representing the entwined powers of church and state, Ehrenberg uses accusations of witchcraft to eliminate rivals, expand his influence, and instill fear.

His insistence on obtaining confessions, regardless of truth, and his manipulation of figures like Engel and the commissioner, underscore his ruthlessness. While rarely seen directly, Ehrenberg’s presence looms over every act of injustice, shaping the moral and political climate of Eisbach.

He is less a man than a symbol of institutionalized oppression, ambition, and the unyielding hunger for control.

Themes

Mass Hysteria and Collective Violence

The villagers of Eisbach, gripped by a series of gruesome child murders and unexplained misfortunes, fall rapidly into a state of hysteria that fuels both suspicion and persecution. This theme emerges most strongly in the public’s swift descent into irrational fear, turning neighbors against each other and empowering institutional authorities to enact extreme measures.

The people, overwhelmed by grief, fear, and the pressing weight of a long, brutal winter, seek a singular source of blame to explain their suffering. They are not content with ambiguity or the slow course of legal truth—they crave spectacle and absolution through sacrifice.

The crowd that once rallied to find Hermann’s body later cheers at Leon von Kleist’s execution, treating his death not as justice but as a kind of ritual purification. The execution becomes a macabre celebration, exposing how easily human empathy can be suspended when social pressure and fear of the unknown take control.

This hysteria is not just emotional—it is weaponized. The ecclesiastical and civil authorities, especially under the influence of figures like Prince-Bishop Ehrenberg, use fear to maintain control, manipulate outcomes, and seize property.

The Church’s investigations, particularly under Reverend Engel, take on an inquisitorial tone, where confessions are extracted, often through coercion, and guilt is presumed before proof. The villagers are not passive observers in this—they contribute, spreading rumors, accusing neighbors, and even testifying falsely.

The result is a community devouring itself. This widespread paranoia reveals how vulnerable justice is in the face of collective panic, especially when fueled by religious fervor and patriarchal enforcement.

Corruption of Religious and Judicial Authority

The presence of corrupt, self-serving authority figures within both Church and State permeates every level of the story. The prince-bishop, Ehrenberg, exemplifies political manipulation cloaked in divine right.

He orchestrates executions not for truth or salvation, but for land, loyalty, and the projection of power. Reverend Engel, though more enigmatic, serves as a reflection of how moral ambiguity thrives within institutions.

He possesses intelligence and insight, and at times seems to recognize the wrongful deaths occurring under his watch. Yet he rarely intervenes meaningfully to stop them.

His actions are not those of a savior or a seeker of justice, but of a man who protects the institution over the individual. He sanctions Kleist’s coerced confession without protest, delivers Zilla to likely execution, and escorts Ursula to a fate as yet unknown—each time surrendering personal ethics for institutional preservation.

Even those who begin with conviction, like Reverend Stern, become worn down by illness and despair, their voices lost amidst the demands of Church superiors and a bloodthirsty public. The law, meant to serve truth, becomes an instrument of terror.

Confessions obtained under duress are treated as divine revelations. Judicial process is reduced to theater, where the outcome is predetermined, and the accused are merely playing roles in a tragic spectacle.

The novel highlights how easily institutions that claim moral and spiritual authority can become mechanisms of repression when unchecked by compassion, truth, or personal accountability. Justice becomes a performance, and mercy an inconvenience.

Misogyny and the Exploitation of Women

Throughout An Age of Winters, women’s lives are dictated by systems designed to control, subjugate, and condemn them. From Katarin’s early life as a child bride to Zilla’s arrest and Freya’s coerced confession, the narrative is replete with examples of how misogyny is embedded in both religious and social structures.

The smallest acts—using a fertility potion, practicing herbal healing, expressing independence—are seen as threats. These acts are punished not just legally but with social excommunication, violence, and, in many cases, death.

Freya’s tragic suicide, following her wrongful implication in her daughter’s murder, illustrates how quickly a woman’s life can be destroyed by rumor and male authority. Her grief, faith, and innocence are disregarded, while her husband’s betrayal is treated as righteous.

Zilla’s imprisonment follows a similar trajectory. She is strong-willed and self-reliant, and her defiance is interpreted as evidence of diabolism.

Her son, Jon, is manipulated by neighbors eager to seize her land. The Church and court accept his confused statements without scrutiny.

Women are not allowed mistakes, complexity, or even sorrow. They are judged by their conformity to passive virtue, and any deviation marks them as witches or sinners.

Katarin, who at first seems a victim of this structure, eventually uses it to her advantage, manipulating others’ perceptions to rise in status. But her success is also an indictment: the only woman who escapes unscathed does so by becoming as ruthless as the forces arrayed against her.

The theme underscores a society where women’s autonomy is criminalized and their suffering rendered invisible unless it serves a political purpose.

The Mask of Innocence and the Nature of Evil

Katarin’s arc gradually unravels the narrative’s moral compass. Initially framed as a quiet observer and emotionally wounded servant, she ultimately reveals herself to be the orchestrator of many of the tragedies afflicting the village.

Her transformation from a seemingly compassionate helper to a cold, remorseless murderer challenges conventional binaries of good and evil. Katarin’s crimes are not driven by supernatural forces but by very human desires: power, security, affection, and revenge.

Her manipulation of Engel, her betrayals of Margaretha and Walter, and her casual brutality toward children all point to a person capable of calculating cruelty hidden beneath a mask of humility and care.

Unlike the other accused in the novel—many of whom are falsely convicted and executed—Katarin is genuinely guilty. Yet she never faces trial.

Instead, she reinvents herself, first in exile, then in comfort, marrying again and erasing her past. This inversion of justice reveals how evil can flourish when it presents itself in socially acceptable forms.

Katarin’s charm, intelligence, and victimhood make her a convincing figure of trust. Her violence hides in plain sight, protected by the very stereotypes and biases that condemn others like Zilla or Margaretha.

The revelation that she alone thrives while so many innocent women are destroyed speaks to the theme’s unsettling conclusion: evil is not always loud, malevolent, or supernatural. It can be ordinary, charming, and strategic—wearing the face of a devoted servant, a grieving friend, or a loving wife.

Psychological Collapse and the Failure of Empathy

The mental unraveling of both individuals and the community at large is a central force driving the story. Reverend Stern, weakened by physical illness and spiritual disillusionment, loses his ability to connect with his flock.

Engel, burdened with confessions of horror and surrounded by suffering, oscillates between duty and numbness. Ursula’s descent into grief-induced psychosis culminates in violence and ultimately her erasure.

But the most extreme example is Katarin, whose early trauma and isolation gradually erode her sense of right and wrong. Her crimes escalate as her empathy fades.

At first, she helps others out of genuine concern—arranging remedies, supporting grieving mothers, sheltering the vulnerable. But as she becomes consumed by envy, obsession, and ambition, she begins to rationalize harm as necessity.

Her detachment becomes complete by the end, when she abandons her newborn child and reinvents herself without remorse.

The village, too, reflects this psychological degradation. Initially a close-knit, grieving community, it becomes a fractured, suspicious, and vindictive mob.

The failure to support individuals like Ursula or protect children like Jon mirrors the broader moral decay. The theme highlights how emotional fatigue, unprocessed trauma, and unchecked fear corrode empathy.

It also shows the danger of neglecting mental and emotional health in favor of punitive measures and moral rigidity. In An Age of Winters, the absence of compassion—both institutional and personal—allows darkness to thrive unchecked, and those who suffer most are left without recourse or redemption.