Anita de Monte Laughs Last Summary, Characters and Themes

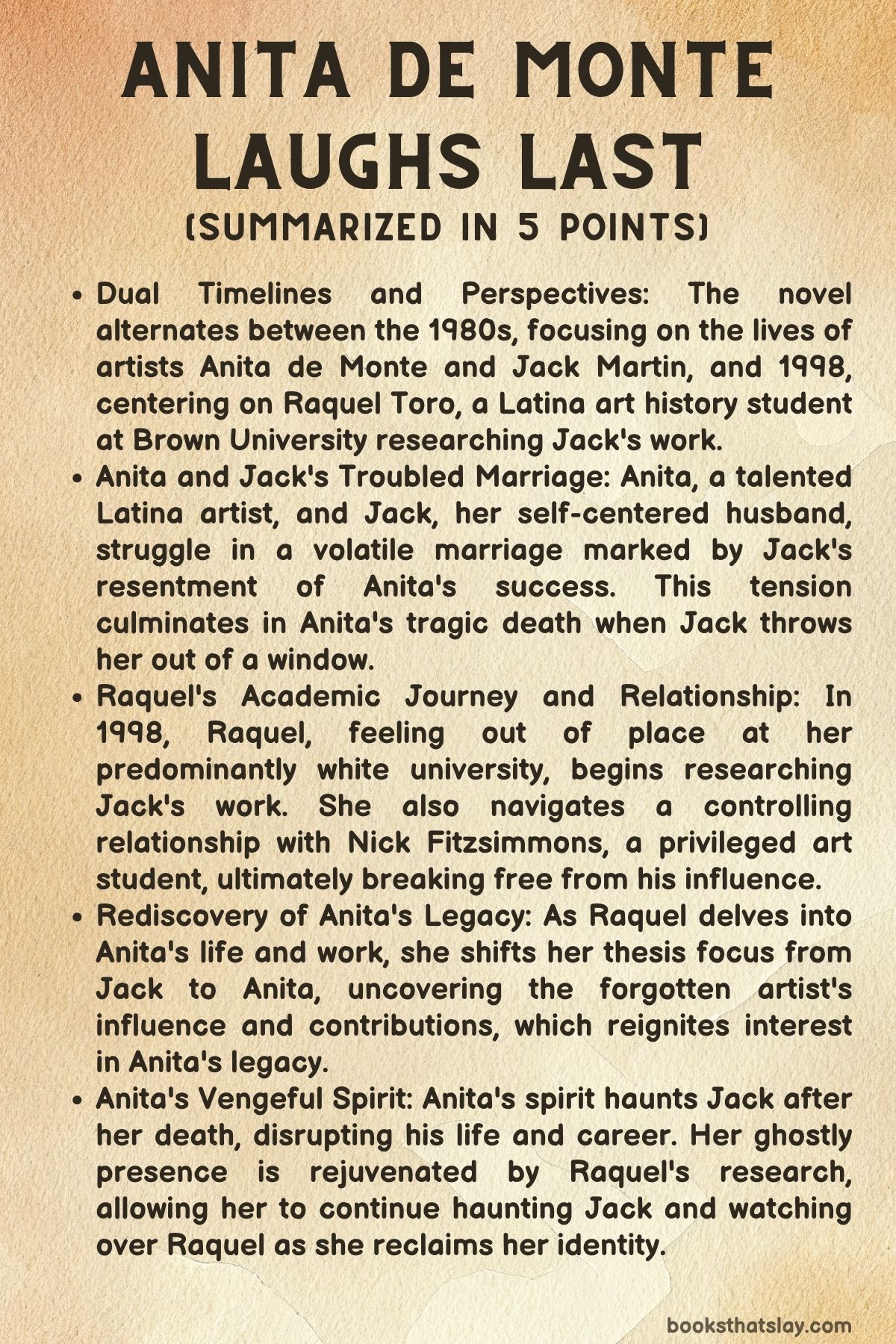

“Anita de Monte Laughs Last” (2024) by Xochitl Gonzalez is a compelling follow-up to her debut, “Olga Dies Dreaming.” This novel brings together themes of art, identity, and the haunting grip of legacy within the lives of its characters.

Set between the 1980s and 1990s, the story explores the intersecting lives of Anita de Monte, a Latina artist, her self-absorbed husband Jack Martin, and Raquel Toro, an ambitious art history student. As Gonzalez masterfully shifts between these timelines, she delves deep into the complexities of ambition, love, and the struggle for recognition in a world that often seeks to erase voices like Anita’s.

Summary

The narrative of “Anita de Monte Laughs Last” unfolds through the intertwined perspectives of three characters: Anita de Monte, an artist; Jack Martin, her husband and fellow artist; and Raquel Toro, an art history student at Brown University.

The story oscillates between the 1980s, when Anita and Jack are at the pinnacle of their careers, and 1998, when Raquel is beginning her research on Jack’s work.

The novel begins by introducing Anita, who is attending a party hosted by Tilly, Jack’s gallerist and confidante. Both Jack and Tilly, who hold Jack’s work in higher regard, are taken aback when they learn that Anita will be featured in her own solo show.

This revelation sets off a chain of events that further strains the already fragile relationship between Anita and Jack.

Switching to 1998, we meet Raquel Toro, a Latina student navigating the predominantly white environment at Brown University. She feels particularly out of place among her peers, especially a group she dubs “the Art History Girls,” who exude an intimidating air of privilege and exclusivity.

Despite this, Raquel is driven by her passion for art and her strong familial ties. She secures a prestigious internship at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and decides to focus her thesis on the work of Jack Martin, encouraged by her advisor, Professor Temple, who is an avid admirer of Jack’s art.

Returning to the 1980s, the novel delves into the turbulent marriage of Anita and Jack.

Jack, egotistical and dismissive, becomes increasingly resentful of Anita’s growing success. He views her not as an equal but as someone who exists to bolster his own status. Their marriage, already strained, begins to unravel as Jack engages in numerous affairs.

Anita, a Latina woman in a predominantly white art world, experiences both subtle and overt forms of discrimination, further alienating her.

Back in Raquel’s timeline, she begins a relationship with Nick Fitzsimmons, a wealthy white student whose parents are influential figures in the New York art scene. Initially dazzled by Nick’s connections and the lavish lifestyle he introduces her to, Raquel soon realizes that Nick views her more as an accessory than a partner.

His controlling behavior, particularly when he drastically cuts her hair against her wishes, signals the toxic nature of their relationship.

Raquel decides to end things with Nick, recognizing that he is more interested in molding her into his ideal rather than accepting her true self.

In the 1980s, tensions between Anita and Jack reach a tragic climax when, during a heated argument, Jack throws Anita out of a window, leading to her death. Though Jack becomes the prime suspect, his gallerist Tilly manipulates the situation to ensure he avoids conviction.

Meanwhile, Anita’s spirit begins to haunt Jack, disrupting his life and career as he struggles to suppress her memory.

Raquel’s research at RISD eventually leads her to discover Anita de Monte’s forgotten work. She is captivated by Anita’s artistry and shifts her thesis focus to explore Anita’s influence on Jack.

This decision revives Anita’s spirit, allowing her to once again torment Jack and, at the same time, guide Raquel in reclaiming her own identity and voice.

Raquel’s thesis is a resounding success, earning her both professional recognition and a renewed sense of purpose.

Characters

Anita de Monte

Anita de Monte is a central figure in the novel, representing both a personal and artistic journey within a predominantly white, male-dominated art world. As a Latinx woman, Anita’s experience in the 1980s art scene is fraught with challenges related to her identity.

She is initially perceived by others, including her own husband Jack, as secondary in talent and importance. However, Anita’s solo show is a pivotal moment that disrupts these perceptions, positioning her as an artist of significant merit.

Despite her success, her marriage to Jack is deeply troubled, marked by his arrogance and resentment. Jack’s belief in his own artistic superiority and his attempts to diminish Anita’s achievements reflect the broader societal tendencies to marginalize women of color.

Anita’s tragic death at the hands of Jack, an act that he manages to evade legal consequences for, underscores the themes of erasure and injustice. Yet, Anita’s spirit is not easily extinguished. Her haunting of Jack, both literally and metaphorically, symbolizes her refusal to be forgotten or silenced.

Even after death, Anita’s influence persists, eventually being revived through Raquel’s discovery of her work. This gives her a form of posthumous justice and recognition.

Jack Martin

Jack Martin is portrayed as the epitome of white male privilege within the art world. His character is marked by deep-seated arrogance, an inflated sense of self-worth, and a profound insecurity masked by his outward success.

Jack’s relationship with Anita is toxic and marked by a lack of respect for her as both an artist and a partner. He sees her primarily as a support figure, an accessory to his own career, rather than as an equal or a competitor.

His resentment of Anita’s success leads to increasingly volatile behavior, culminating in the act of murder. Jack’s ability to escape conviction, largely due to the support of his gallerist Tilly, highlights the systemic biases that protect powerful men at the expense of marginalized voices.

Despite this, Jack is not left unscathed. Anita’s haunting presence disrupts his life and career, suggesting that while he may evade legal justice, he cannot escape the consequences of his actions on a deeper, psychological level.

Raquel Toro

Raquel Toro serves as a modern parallel to Anita, navigating her own struggles as a Latinx woman in a predominantly white academic and social environment. As an art history student at Brown, Raquel feels the weight of her differences, particularly in the face of the elitism and exclusivity of the art world.

Her relationship with Nick Fitzsimmons, an affluent white student, mirrors the dynamic between Anita and Jack, with Raquel initially seduced by the allure of his status and connections. However, as the relationship progresses, Raquel becomes increasingly aware of Nick’s possessiveness and his attempts to reshape her identity to fit his ideals.

The symbolic act of cutting her hair, which Nick takes much further than agreed upon, represents his desire to control and diminish her individuality. Raquel’s eventual decision to leave Nick marks a crucial moment of self-assertion and independence.

Her discovery of Anita de Monte’s work becomes a turning point, as she shifts her academic focus to explore Anita’s influence. Ultimately, Raquel revives Anita’s legacy, establishing her own career while serving as a form of restitution for the wrongs done to Anita. This connection links the two women across time.

Nick Fitzsimmons

Nick Fitzsimmons embodies the insidious nature of privilege and control within personal relationships. As a wealthy, white art student with connections in the New York art world, Nick initially appears to be an ideal partner for Raquel, offering her access to a world that she finds both intimidating and desirable.

However, Nick’s true nature gradually reveals itself through his controlling behavior and subtle forms of manipulation. His insistence on Raquel changing her appearance, particularly his drastic cutting of her hair, symbolizes his desire to mold her into a version of herself that aligns with his expectations rather than accepting her as she is.

Nick’s actions highlight the racial and gender dynamics at play in their relationship, where Raquel’s identity and autonomy are constantly undermined. His inability to connect with Raquel’s family and his condescending attitude towards her background further emphasize his deep-seated biases.

Ultimately, Nick’s failure to appreciate Raquel as an equal partner leads to the dissolution of their relationship, which serves as a critical moment in Raquel’s journey towards self-empowerment.

Tilly

Tilly, the gallerist, is a secondary but significant character in the narrative. She represents the complicity of those who enable and protect figures like Jack Martin.

As both a friend and professional ally of Jack, Tilly plays a crucial role in shaping his career and shielding him from the consequences of his actions. Her intervention in the aftermath of Anita’s death, using her influence to help Jack avoid conviction and to erase Anita’s legacy, underscores the systemic power imbalances in the art world.

Tilly’s character is complex, as she is both a successful woman in a male-dominated industry and an enabler of Jack’s toxic behavior. Anita’s haunting of Tilly, especially her transformation into a bat to terrorize her, serves as a form of poetic justice. This serves as a reminder that Tilly’s actions have not gone unnoticed or unpunished.

Professor Temple

Professor Temple is Raquel’s advisor at Brown and a significant figure in guiding her academic journey. As an admirer of Jack Martin’s work, Professor Temple initially steers Raquel towards studying Jack, reflecting the broader academic and cultural bias towards celebrating male artists, often at the expense of equally talented women.

However, Professor Temple’s support of Raquel’s work, even as it shifts focus to Anita de Monte, suggests a willingness to recognize and correct this imbalance. His character represents the potential for change within institutions, as he ultimately endorses Raquel’s exploration of Anita’s legacy, helping to bring her story to light.

Themes

The Intersection of Art, Identity, and Power in a Predominantly White World

In Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Xochitl Gonzalez delves deep into the intersection of art, identity, and power within a predominantly white and male-dominated world. The novel intricately weaves the struggles of Latinx women like Anita and Raquel as they navigate the art world, which both marginalizes and commodifies their identities.

Anita, a talented artist in her own right, finds her achievements overshadowed by her husband’s arrogance and the broader art world’s unwillingness to recognize her beyond stereotypes. This dynamic highlights the power structures within the art industry, where white male artists like Jack are elevated and celebrated, often at the expense of women and people of color.

Raquel’s journey mirrors Anita’s, as she confronts the subtle and overt racism at Brown University and within her personal relationships. Her transformation from a passive observer of art history to an active participant in reclaiming Anita’s legacy underscores the theme of power reclamation and the importance of challenging the status quo.

The Ghosts of Historical Erasure and Cultural Memory

Gonzalez’s novel explores the concept of historical erasure and cultural memory through the spectral presence of Anita de Monte. Anita’s spirit represents the countless marginalized voices in art and history that have been silenced or forgotten.

Her haunting of Jack symbolizes the unresolved tension between the erasure of minority contributions and the persistence of cultural memory. Although Anita’s physical presence is erased by her death and Jack’s subsequent efforts to suppress her legacy, her spirit endures as a testament to the indelible mark she left on the world.

This theme extends to Raquel’s academic journey as she unearths Anita’s influence, effectively resurrecting her memory and challenging the dominant narratives that have sought to erase her. The novel thus becomes a meditation on the power of art and scholarship to reclaim lost histories and the ways in which cultural memory can serve as a form of resistance against erasure.

The Intersectionality of Gender, Race, and Class in Romantic and Professional Relationships

The novel intricately examines the intersectionality of gender, race, and class, particularly within the context of romantic and professional relationships. Anita’s marriage to Jack is fraught with the dynamics of gendered power, where her Latinx identity is both fetishized and devalued by her white husband.

Jack’s infidelity and ultimate act of violence against Anita are not just personal betrayals but also symbolic of the broader societal violence inflicted on women of color. Similarly, Raquel’s relationship with Nick Fitzsimmons reveals the insidious ways in which race and class intersect to complicate notions of love and partnership.

Nick’s attempts to control Raquel’s appearance and his condescending attitude toward her heritage expose the deep-seated racism and classism that underpin their relationship. Raquel’s eventual rejection of Nick and her embrace of her cultural identity signify a rejection of these oppressive structures. This highlights the novel’s broader critique of the ways in which race, gender, and class intersect to shape the experiences of Latinx women.

The Role of Art as a Medium for Social and Political Resistance

Art in Anita de Monte Laughs Last is not merely a form of personal expression but a powerful medium for social and political resistance. Anita’s artwork, which initially garners recognition only to be overshadowed by her husband’s career, becomes a site of struggle against the forces that seek to diminish her legacy.

Her posthumous influence, revived through Raquel’s thesis, underscores the capacity of art to challenge dominant narratives and assert the presence of marginalized voices. Raquel’s decision to shift her academic focus to Anita de Monte, despite the initial pressure to conform to established academic and artistic standards, is itself an act of resistance.

By doing so, Raquel not only honors Anita’s contributions but also asserts the importance of diverse perspectives in art history. This theme emphasizes the novel’s broader message about the transformative power of art and scholarship in contesting social injustices and rewriting history from the margins.

The Haunting of the Past and the Pursuit of Justice

The novel’s use of Anita’s ghost to haunt Jack and later guide Raquel speaks to the broader theme of the haunting of the past and the pursuit of justice. Anita’s spirit, though weakened over time, represents the unresolved injustices that continue to linger in the present.

Her haunting of Jack serves as a metaphor for the ways in which the past cannot be easily forgotten or dismissed, particularly when it involves acts of violence and erasure. This theme is further complicated by the novel’s portrayal of Raquel’s journey, which becomes a quest to uncover and rectify the wrongs done to Anita.

Raquel’s work to restore Anita’s place in art history is not just an academic exercise but a moral imperative to seek justice for those who have been wronged by history. In this way, the novel suggests that the pursuit of justice is an ongoing process. It requires confronting the ghosts of the past and ensuring that their stories are told.