Apartment Women Summary, Characters and Themes

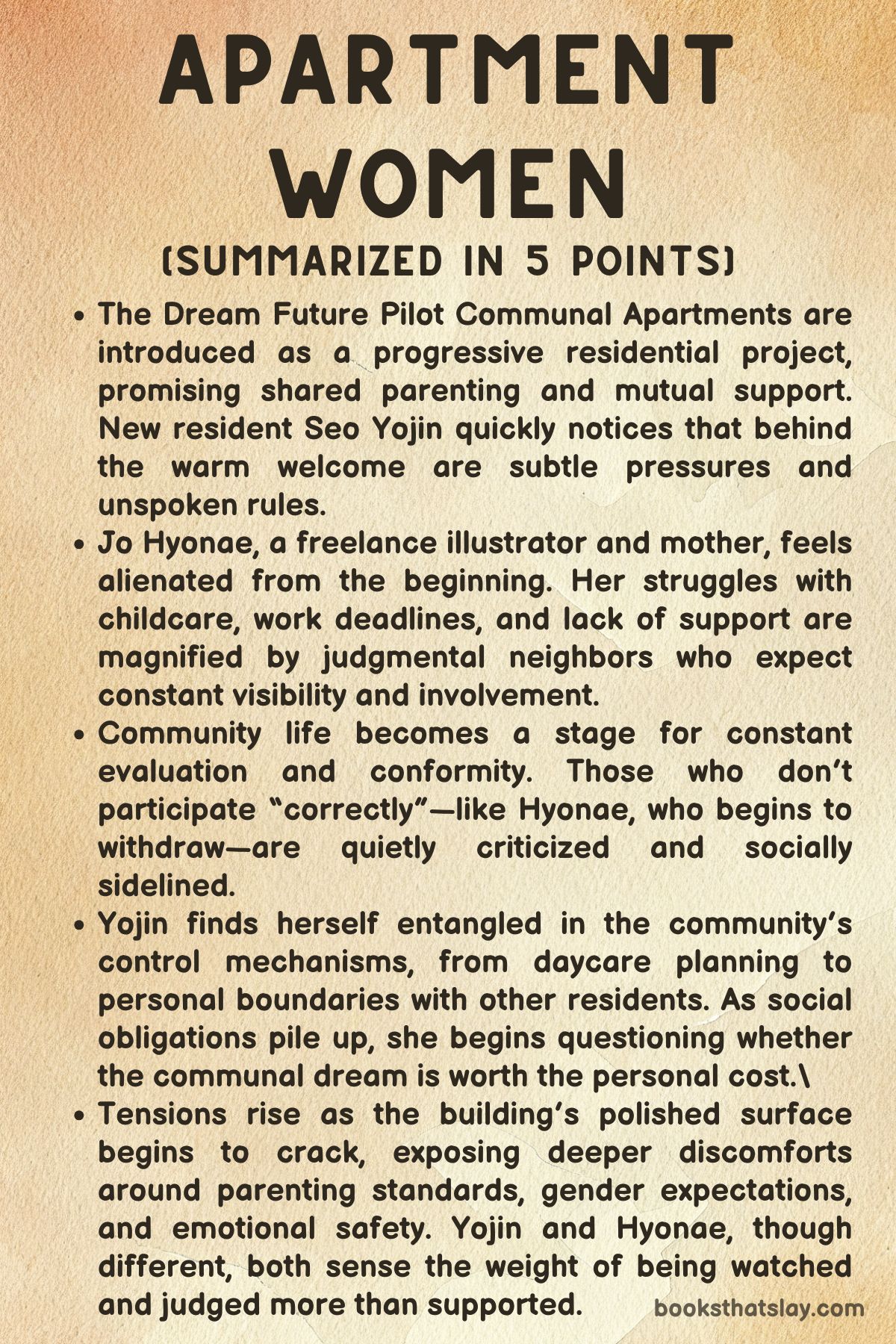

Apartment Women by Gu Byeong-mo is a quiet, sharp, and layered novel that examines the fragile infrastructure of idealized community living. Set within a government-designed apartment complex meant to promote collective family life, the novel presents a stark contrast between policy-driven utopia and real-world emotional strain.

Through the experiences of Yojin, a reserved pharmacy assistant, and her neighbors, we observe how forced proximity amplifies invisible labor, repressed desires, and social expectations. The novel doesn’t rely on large dramatic events but instead focuses on the friction of daily interactions, illuminating the burdens women bear in maintaining civility, appearance, and emotional harmony in the name of community.

Summary

Apartment Women opens with Yojin and her family—husband Euno and daughter Siyul—moving into a new communal housing complex. The space is part of a government initiative designed to encourage large families through shared resources and responsibilities.

At their welcome gathering around an imposing backyard table, Yojin is met with smiles that barely mask control and conformity, especially from Danhui, a leading voice in the apartment’s community culture. Danhui champions collective ideals, but her constant surveillance and personal probing highlight the tension between public friendliness and private policing.

Yojin, soft-spoken and not particularly social, finds herself navigating this environment with quiet apprehension. Her husband is unemployed, and while she works as a pharmacy assistant, she’s consistently treated as if she lacks ambition or sophistication.

As the neighborhood begins to impose expectations, Yojin grows wary of Danhui’s enthusiasm, which often crosses personal boundaries.

Among the residents is Hyonae, a freelance illustrator and new mother. She is judged harshly by others for her aloofness and failure to participate in communal duties.

Through her eyes, we see the toll of balancing motherhood with a physically demanding career. Her insistence on working by hand, rather than going digital, marks her resistance to technological shortcuts but also adds to her exhaustion.

Her artistic discipline becomes symbolic of the personal sacrifices many women make to retain a sense of self, even as they are overwhelmed by domesticity and motherhood.

Yojin becomes further entangled in the social fabric when she’s roped into carpooling Danhui’s husband, Jaegang. The arrangement begins as a logistical convenience but soon reveals emotional undercurrents.

Jaegang offers her gifts, speaks inappropriately, and eventually makes a move that Yojin finds unsettling. His hand brushing her cheek—seemingly innocuous—awakens a lifetime of buried discomfort.

Yojin’s internal response is not explosive, but conditioned and resigned. She doesn’t confront Jaegang but instead adds this moment to her collection of normalized violations, a reflection of societal expectations placed on women to endure rather than react.

As community leaders like Danhui and Jaegang begin to push for a shared childcare initiative, Yojin hesitantly agrees, though she doubts its sustainability. Her doubts come to life when her daughter Siyul is scratched by another child, and she is forced to mediate without any support or accountability.

This moment reflects the gap between theoretical collective parenting and the messy, often unspoken realities of children’s interactions.

Parallel to Yojin’s storyline is the narrative of Gyowon, another mother in the complex. Once a homemaking influencer, she is now mocked for her thriftiness and struggles financially.

Her husband Yeosan is emotionally distant and financially unreliable. A violent domestic altercation one night shatters the illusion of harmony in the complex.

When neighbors intervene, they do so hesitantly, and the next day, no one addresses the incident directly. The trauma is buried under the pressure to keep things running smoothly.

Euno, Yojin’s husband, becomes drawn to Gyowon through shared interests in film. Their bond begins innocently enough, but Yojin is troubled by how easily Euno prioritizes these adult conversations while neglecting parental responsibilities.

Her frustration builds when she comes home early one day to find Gyowon and Euno enjoying pizza while Siyul is left alone, tasked with watching other children. This moment pushes Yojin to a breaking point.

She decides she can no longer carry the emotional and physical burdens of her family and this community by herself. She leaves with Siyul, recognizing that her quiet endurance has only enabled the disregard of her needs.

Gyowon’s arc mirrors Yojin’s in many ways. She grapples with the decay of her marriage and the realization that no amount of online validation or domestic perfection can make up for betrayal and emotional exhaustion.

Her momentary reprieve—an outing to a kid’s café with Euno—offers fleeting companionship but cannot undo the structural failure of her home life.

As families unravel and leave, the narrative passes to a new arrival, a hopeful mother-to-be who tours the nearly empty complex with Seah’s mother, the only remaining resident. Seah’s mother recounts the stories of those who departed: one escaping abuse, one fleeing financial instability and emotional neglect, and Yojin, who left to reclaim her autonomy.

The newcomer sees potential, optimism clouding her view of what really happened in the apartments.

The final image is of the communal table—immense and immovable—symbolizing both the ideals of togetherness and the heavy expectations that come with it. It stands as a monument to a vision of shared life that failed to account for personal trauma, unspoken labor, and the emotional realities of its residents.

While the complex was intended to nurture connection, it instead revealed how communal living can demand performance over authenticity, and how silence is often mistaken for harmony.

In the end, Apartment Women is not a critique of community itself, but of the societal and gendered dynamics that shape it. It questions who gets to define the rules, who bears the emotional labor, and what happens when idealistic policies are layered onto flawed human relationships.

Through the lives of its female residents, the novel gently but unsparingly shows how survival often means stepping away from what was promised in search of something more quietly dignified: space, privacy, and the right to say no.

Characters

Yojin

Yojin is the emotional and narrative anchor of Apartment Women, embodying the nuanced contradictions of motherhood, marriage, and communal living. As a pharmacy assistant and mother to Siyul, she exists in a liminal space between passivity and resilience.

From the outset, Yojin is marked as an outsider—quiet, economically modest, and reluctant to expose herself to the superficial cheer of the communal housing collective. Her restraint is not rooted in hostility but in self-preservation, a learned response from years of being overlooked and subtly patronized.

Her initial attempts to conform—graciously accepting hospitality, tolerating prying questions, and going along with communal decisions—are driven by a quiet hope for belonging, yet she remains deeply aware of the social posturing at play.

As her interactions with Jaegang, Danhui’s husband, grow increasingly uncomfortable, Yojin becomes the lens through which the reader witnesses the creep of boundary violations cloaked in friendliness. Her internal monologue reveals the cumulative burden of microaggressions and unwanted advances she has endured throughout her life—how these moments have taught her not to react for fear of social reprisal.

She is not naive, nor is she complicit; rather, she is caught in a cultural and personal paralysis where reacting can often cost more than enduring. Even as her husband Euno’s inattentiveness adds to her emotional isolation, Yojin remains composed—until the final rupture, when she decides to leave the complex with Siyul.

Her departure is not an act of escape alone, but a declaration that she will no longer allow herself or her child to be shaped by an environment that masks intrusion with idealism.

Hyonae

Hyonae represents the brutal intersection of creative ambition and maternal exhaustion. A freelance illustrator and mother, she carries the invisible weight of postpartum depression, professional instability, and social expectations.

In a space that prioritizes visibility and participation, Hyonae becomes an easy target for criticism, particularly from Danhui, who sees her nonparticipation as selfish or negligent. Yet, beneath her perceived aloofness lies a woman battling not only the physical demands of new motherhood but the deeper existential struggle of identity erosion.

Her choice to continue working with traditional tools instead of digital shortcuts speaks to a desire for authenticity and a connection to something real in a world that demands performance and polish.

Her past traumas—her child’s accident with paint, the judgmental scrutiny from family—underscore how fragile her existence is and how high the stakes are for any perceived failure. She is not disengaged because she is indifferent; she is retreating because survival itself requires her full capacity.

Hyonae’s pain is quiet but resonant, a testament to the silent battles waged by mothers who are artistically driven yet constantly forced to choose between selfhood and caregiving. She remains one of the most poignant figures in the story—a woman broken not by lack of effort but by the unrelenting demand to be everything at once.

Danhui

Danhui is both a caricature and a deeply believable portrait of performative community leadership. She thrives in the structure and social capital of the communal living project, inserting herself into every welcome, decision, and organizational effort with a forceful cheerfulness that borders on coercion.

Her friendliness is not without calculation; it is a mechanism of control and self-elevation. She leverages her visibility and verbal assertiveness to enforce standards of behavior, projecting an image of harmony while quickly othering those who fail to meet her expectations.

Yet Danhui is not evil or malicious in a traditional sense. She believes in the collective ideal, but in doing so, fails to acknowledge the individual struggles within it.

Her inability to see Hyonae’s fatigue or Yojin’s discomfort reveals a blind spot bred by privilege and a desire for order. Danhui’s actions reflect the pressure to curate not only one’s life but the community’s image—an aspiration that masks real vulnerabilities and alienates those unwilling or unable to match her energy.

Through her, the novel critiques how leadership in communal settings can morph into soft authoritarianism when driven by ego more than empathy.

Jaegang

Jaegang is one of the most unsettling characters in Apartment Women, precisely because he operates under the guise of benevolence. As Danhui’s husband and Yojin’s carpool partner, he initially appears helpful and generous, offering brunches and conversation.

But his behavior soon crosses boundaries—his gifts grow inappropriate, his jokes suggest more than neighborly interest, and his actions take on a predatory undercurrent, most notably when he makes an unsolicited, intimate gesture toward Yojin. Jaegang symbolizes a particular breed of male entitlement that thrives in systems where women are conditioned to doubt their discomfort.

His manipulation is subtle, framed as jest or goodwill, but it functions to test how far he can go without consequence. What makes him particularly insidious is that he never explodes into obvious villainy; instead, he persists through the quiet erosion of Yojin’s personal space and agency.

His presence forces readers to confront how often violations occur not through overt violence but through accumulated, tolerated offenses that become normalized. Jaegang’s character exposes the limits of accountability in communal spaces where everyone is watching, but no one truly sees.

Euno

Euno, Yojin’s husband, is a character defined more by his absence than his presence. His emotional passivity and detachment mirror the systemic undervaluing of women’s labor, both domestic and emotional.

Euno is not abusive or antagonistic; he is simply disengaged. He bonds with Gyowon over films, enjoys adult conversations, and fails to recognize—or chooses not to confront—the weight of Yojin’s struggles.

When left to supervise children, he falters, prioritizing leisure over responsibility. His lack of attentiveness becomes especially grating when Yojin finds him eating pizza with Gyowon while their daughter, Siyul, is left alone to care for other children.

Euno’s character critiques the quiet complicity of men who enjoy the benefits of communal or marital structures without contributing equitably to their maintenance. He is a man unmoored, finding solace in fleeting connections while his wife bears the emotional brunt of family and community demands.

His failure to notice or respond to Yojin’s emotional fatigue is not just a marital flaw—it is a societal one, reflected in countless relationships where women are the default caregivers and men, the optional participants.

Gyowon

Gyowon is a complex, wounded figure who enters the story already burdened by betrayal, economic uncertainty, and emotional depletion. Once devoted to presenting an ideal life—through tidy interiors and aspirational social media posts—she has been disillusioned by public shaming and private collapse.

Her husband’s financial recklessness and the betrayal of her extended family have left her bitter and guarded. Yet, in Euno, she finds a rare moment of shared empathy and attention, though their connection remains more therapeutic than romantic.

Her pain is raw and deeply human. She yearns for control, validation, and reprieve—none of which her environment can consistently provide.

Her altercation with Yeosan marks a breaking point, an eruption of long-simmering resentment and frustration. Despite these explosive moments, Gyowon is not unlikable; she is deeply sympathetic.

Her descent reflects the emotional costs of striving for appearances in a society that offers little support for those who fall behind. Like Yojin and Hyonae, she is a casualty of a system that glorifies collective living but offers no real mechanisms to absorb individual grief.

Siyul

Siyul, Yojin’s young daughter, is a subtle but crucial presence in Apartment Women, representing both hope and vulnerability. She is often caught in the crossfire of adult expectations, asked to be responsible beyond her years in an environment that treats communal parenting as an unexamined good.

Her incident of being scratched by other children and left unsupervised while the adults socialize points to the latent dangers of shared living ideals without sufficient accountability. Siyul’s experiences expose the flawed assumptions that children will naturally adapt to collective dynamics without structured oversight.

Though she has limited dialogue or agency, Siyul functions as a barometer for the story’s emotional climate. Her well-being, or lack thereof, serves as a mirror to Yojin’s growing disillusionment.

In many ways, it is Siyul’s neglect—not by her mother, but by the communal apparatus—that catalyzes Yojin’s final decision to leave. In doing so, Siyul becomes a symbol of the future Yojin refuses to compromise on—a future that demands safety, respect, and the right to boundaries.

Themes

Emotional Labor and the Burden of Performing Stability

The women in Apartment Women exist under constant emotional pressure to present themselves as cooperative, composed, and integrated members of the community, even when their private lives are in disarray. Yojin, Hyonae, and Gyowon, in particular, serve as case studies for how women are socially conditioned to absorb stress quietly while maintaining a facade of composure.

Yojin’s polite deflections, Hyonae’s guilt-laden internal dialogues, and Gyowon’s social media curation of domestic bliss are not just coping mechanisms—they are survival strategies in a world that demands self-effacement and cheerful participation. The emotional labor they perform is unpaid, unnoticed, and often extracted under the pretense of community spirit.

When Danhui orchestrates communal obligations, it’s clear that her version of leadership rests on subtle coercion, shaming others into compliance while masking it as camaraderie. The expectation for women to manage their emotions, regulate conflict, soothe tensions, and “pitch in” to an exhausting standard is portrayed not as noble or empowering, but as quietly depleting.

The novel refuses to glamorize these social negotiations; instead, it shows how the constant need to manage appearances—whether through smiling through discomfort, tolerating inappropriate behavior, or pretending contentment in broken marriages—becomes a silent, cumulative burden. The communal table may symbolize shared meals and collective effort, but it also stands as a monument to the emotional compromises and sacrifices women must make to uphold the illusion of harmony.

The Fragility of Idealized Community Living

The government-sponsored co-op apartment complex is introduced as a hopeful social experiment—an attempt to incentivize families into child-rearing and communal participation. But Apartment Women systematically unpacks how quickly these utopian ideals collapse when confronted with real human behavior.

The community is less a sanctuary than a crucible where tensions simmer, resentments fester, and alliances are forged through performance rather than genuine connection. From the very beginning, Yojin senses that behind the polite smiles lies an unspoken hierarchy.

Danhui sets the tone, asserting dominance through a combination of overbearing warmth and moral policing. The rules of the community are unspoken but deeply entrenched: noncompliance is met not with formal sanctions, but with whispers, exclusion, and condescension.

The novel lays bare how fragile these social structures are when residents fail to perform their designated roles. Hyonae is ostracized for being visibly overwhelmed, Gyowon is humiliated online for being frugal, and Yojin’s attempts to quietly endure boundary violations are ultimately met with more overreach.

What begins as a gesture toward collective parenting ends in fractured households, bruised egos, and exits. The shared table that once welcomed newcomers becomes a relic of false promises.

By the end, with three families gone and only one heavily pregnant woman left behind, the failure of the community is complete. The incoming new family reads the space as full of potential, but the reader understands it as a vacuum—a place where ideals once flourished, only to be buried under the weight of unmet expectations and unresolved conflict.

Gender, Power, and Consent

The novel is acutely attuned to the subtleties of gendered power dynamics, particularly in how they manifest through physical space, social obligation, and emotional manipulation. Yojin’s experience with Jaegang is a masterclass in how boundary violations can be normalized under the veneer of friendliness.

His gestures—at first flattering, then gradually more invasive—are designed to entrap her in a dynamic where resistance would seem ungrateful or unfriendly. The moment he touches her face is not just a physical breach but a culmination of a long chain of silent transgressions.

Yet Yojin, conditioned by years of enduring unwanted attention without complaint, shrugs it off—not out of indifference, but because social penalties for naming such violations are steep. This power imbalance is mirrored in other areas: Gyowon’s husband uses their shared finances for selfish ends, while she is left to defend the illusion of prosperity; Danhui weaponizes her leadership role to enforce gendered norms, expecting women to carry the weight of childcare and social upkeep while men, like Jaegang, coast on goodwill and charm.

Even children are pulled into this structure: Siyul is attacked and blamed for not managing younger kids properly, despite never consenting to the role of caretaker. In all of these situations, the question of consent—both explicit and tacit—haunts the interactions.

Women are expected to comply, endure, and excuse. The novel doesn’t offer catharsis or confrontation; instead, it charts how deeply ingrained these power asymmetries are, and how they shape the choices women feel they are allowed to make.

Marriage and the Erosion of Intimacy

Rather than portraying marriage as a stable institution, Apartment Women exposes it as another arena where performance often replaces genuine intimacy. Each marriage in the novel is defined by emotional disconnection, unspoken dissatisfaction, or outright betrayal.

Yojin’s relationship with Euno is polite but hollow; her increasing frustration with his passivity and his emotional availability to Gyowon highlights the quiet ways couples drift apart. Euno doesn’t cheat in the physical sense, but his attention, interest, and energy are spent elsewhere—not on his wife or daughter.

Yojin, who has long endured being unseen, reaches her limit not because of a dramatic infidelity, but because of a pattern of disregard that becomes too stark to ignore. Gyowon’s marriage is even more fraught.

Her husband’s financial recklessness and refusal to acknowledge their mounting problems reveal a relationship built on deception and unequal burdens. Meanwhile, Danhui and Jaegang’s marriage, superficially efficient and unified, masks a dynamic in which Jaegang feels entitled to flirt with other women while Danhui expends energy enforcing social norms.

In each case, the emotional needs of the wives go unmet while the husbands either ignore problems or create new ones. The communal setting only magnifies these fissures.

Shared spaces offer no privacy, and everyone becomes a spectator to everyone else’s failures. In this way, the story suggests that communal living does not intensify intimacy—it exposes its absence.

The final departures of the women from the complex are not just moves away from a failed social project, but quiet declarations of independence from marriages that offered no real companionship or respect.

Motherhood, Isolation, and Societal Judgment

In the lives of the mothers portrayed in Apartment Women, the act of parenting is not just physically demanding but emotionally isolating. Hyonae’s story is a vivid portrayal of the invisible, relentless pressures faced by new mothers.

She is shamed for working, for not participating enough, for being tired, for failing to embody the ideal maternal image. Even when her child’s safety is jeopardized, the focus shifts to whether she’s managing properly rather than what support she needs.

Yojin, too, must constantly prove that she is a good mother, especially when Siyul is expected to be a surrogate caretaker for younger children in the community. Yet no one offers her resources or respite—just expectations.

Gyowon’s carefully curated domestic life, filled with secondhand toys and thrifted goods, is mocked online by people who fail to see the care behind her efforts. The cumulative message is clear: no matter what a mother does, it is never enough, and often open to critique.

These women are not allowed to simply be—they must constantly justify their choices, conceal their fatigue, and maintain appearances for both community approval and social media validation. The shared childcare initiative, rather than relieving their burdens, simply redistributes them under new supervision.

What’s particularly striking is the lack of genuine empathy; communal parenting is less about sharing responsibilities than about policing one another’s parenting styles. The mothers in this story do not find solidarity—they find surveillance.

This theme underscores the profound loneliness that can accompany motherhood, especially in systems designed more to observe than to support.