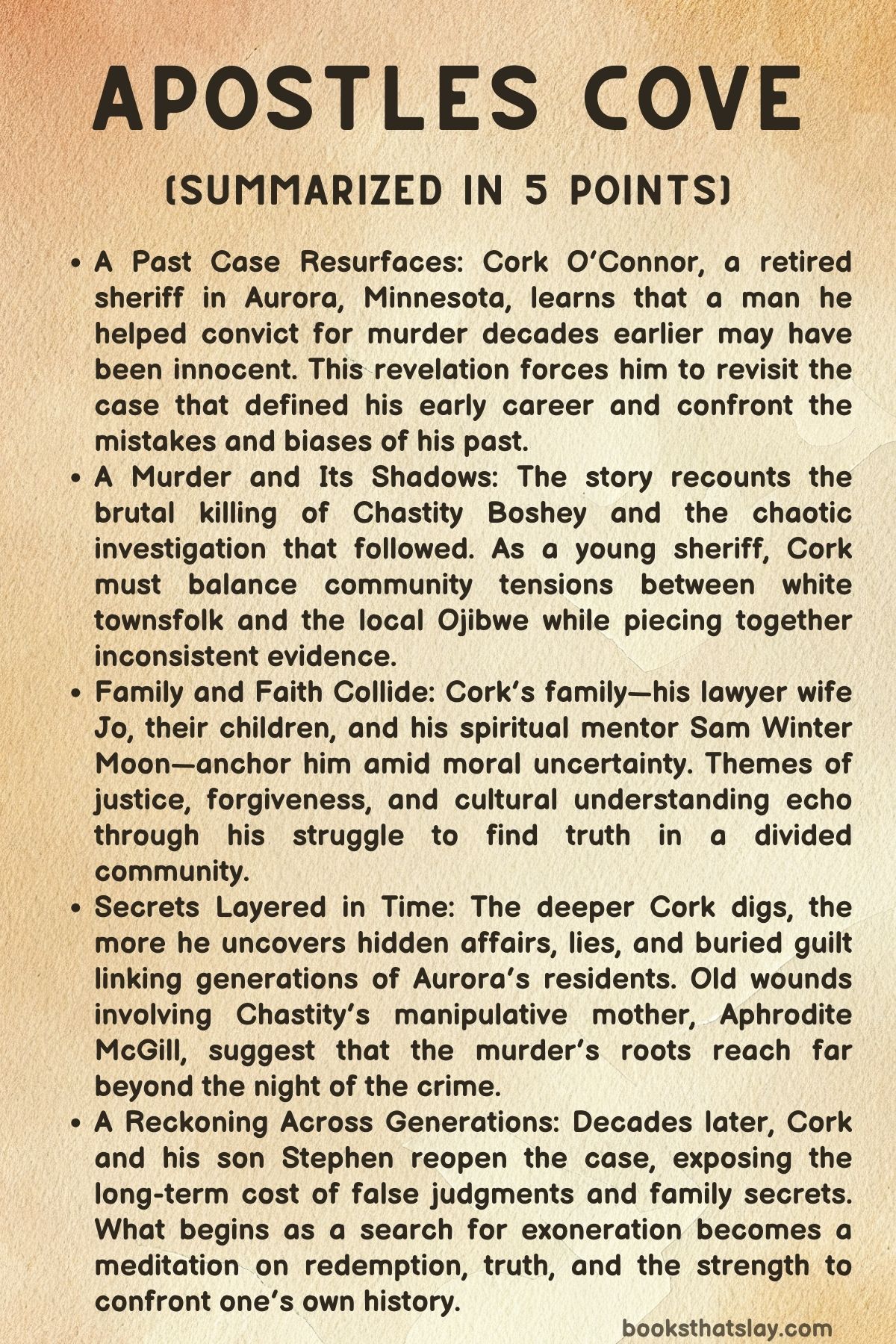

Apostle’s Cove Summary, Characters and Themes

Apostle’s Cove (Cork O’Connor #20) by William Kent Krueger is a deeply layered mystery set in the small Minnesota town of Aurora, where justice, memory, and redemption intertwine through the eyes of Cork O’Connor, a former sheriff facing the haunting weight of his past. When new evidence suggests a man he once convicted for murder may have been innocent, Cork must reopen wounds long buried and confront the moral complexities of truth and guilt.

Blending crime investigation with emotional introspection and a profound sense of community, the novel explores how trauma echoes through generations and how forgiveness can emerge even from the darkest corners of human experience.

Summary

The novel begins in late autumn in Aurora, Minnesota, where Cork O’Connor is preparing to close his seasonal diner, Sam’s Place, for the winter. Feeling the passage of time and a growing melancholy, he receives a phone call from his son Stephen, a law student working for the Great North Innocence Project.

Stephen reveals that new evidence indicates Axel Boshey—a man Cork helped convict twenty-five years ago for murdering his wife, Chastity—may have been innocent. The revelation pulls Cork back into one of the most painful cases of his early career.

Years earlier, when Cork was the newly appointed sheriff of Tamarack County, he received a call about a stabbing at the Timber Lodge and Resort. Upon arriving, he found Chastity Boshey dead and her mother, Aphrodite McGill, in shock beside the body, holding a knife.

Aphrodite accused her son-in-law Axel of the killing, claiming he had “butchered” her daughter. The scene was chaotic—blood everywhere, a crying baby in another room—and the initial evidence appeared to confirm Aphrodite’s accusation.

Cork began investigating, learning from Aphrodite that Chastity and Axel had argued the night before and that Axel had been drinking. When Cork visited Axel’s mother, Patsy Boshey, on the Ojibwe reservation, she insisted her son could not have committed such a crime but admitted he had left his child with her that night and had not returned.

Cork, already under pressure from the community and local media, sought guidance from his mentor, Sam Winter Moon. Sam urged him not to let prejudice against Native suspects color his judgment.

As Cork pursued the case, evidence began to mount against Axel: bloodstained clothes in his woodshed, Chastity’s and Aphrodite’s fingerprints on the knife, and a missing murder weapon—a fireplace poker later found wiped clean. Axel was soon arrested after a tense standoff at his mother’s home, during which Cork’s friend Sam helped defuse the situation.

Axel, confused and drunk, could not remember whether he had killed his wife. His despair and lack of clarity only deepened Cork’s doubts about the case.

During interrogation, Axel admitted to heavy drinking and frequent arguments with Chastity. When Cork’s wife, Jo, an attorney, intervened, she stopped the questioning and agreed to represent Axel.

Despite Jo’s concerns about inconsistencies in the evidence, the community’s anger intensified. The media painted Axel as a violent man, and the sheriff’s department, under political pressure, pushed for conviction.

The deeper Cork dug, the stranger the connections became. Axel had once been suspected—but acquitted—of killing Clyde Greensky, Chastity’s first husband and his cousin.

Chastity’s relationships, her mother’s influence, and the town’s racial tensions blurred the lines between guilt and prejudice. When Cork and Larson, his deputy, discovered Axel had been romantically involved with Bernadette Polaski, the town librarian, suspicion widened.

Bernadette claimed Axel was with her the night of the murder, providing an alibi that seemed too convenient.

As Cork revisited the case’s emotional landscape, old wounds reopened. Aphrodite McGill’s history of manipulation and her decadent lifestyle at Shangri-La—a so-called spiritual retreat tinged with scandal—surfaced.

Cork questioned her motives and possible role in Chastity’s troubled upbringing. It became clear that Aphrodite’s household was filled with secrets, including her toxic control over her daughter and disturbing influence on the family’s children.

Years later, in the present timeline, Cork meets with Stephen and Sunny Boshey—Axel and Chastity’s grown son—along with Marianne Polaski, Bernadette’s daughter. DNA tests reveal both Sunny and Marianne are Axel’s children, proving Axel’s complicated entanglements.

Sunny, convinced of his father’s innocence, begs Cork to reinvestigate. Axel, now an older man transformed by faith and years in prison, admits that he once confessed falsely to protect Bernadette, who was pregnant and whom he believed might have been involved.

Cork reopens the cold case, revisiting witnesses and piecing together fragments of truth. The evidence begins to point toward Aphrodite McGill as the central manipulator in a web of deceit.

Cork’s renewed investigation leads to an assault that nearly kills him, a warning that the past is still dangerous.

The case comes to a head when a new crime surfaces: Lucy Martinelli, a woman long believed dead, is found alive under the name Magdalene. She is the daughter of Wild Bill Gunderson and connected to the original murder through her mother’s death.

When a hostage situation erupts at a cabin, Cork, his daughter Jenny, Sheriff Marsha Dross, and former priest Jude Monroe rush to intervene. Inside, Lucy holds Wild Bill and her ex-husband, Rocky Martinelli, at gunpoint.

As Jude negotiates, long-buried truths emerge.

Rocky confesses that on the night of Chastity’s murder, Aphrodite arrived at the cabin where Chastity and Rocky were having an affair. A fight ensued—Chastity armed with a knife, Aphrodite with a fireplace poker.

In a frenzy, Aphrodite bludgeoned and stabbed her daughter to death. Rocky and Wild Bill then staged the scene to frame Axel, hiding the bloody evidence.

Later, Aphrodite’s memory blurred from drugs and alcohol, she convinced herself Axel was guilty. Lucy, traumatized by years of abuse and manipulation, repressed what she had seen and lived believing she was the killer.

The revelations bring long-awaited justice. Sheriff Dross arrests Rocky and Wild Bill for their roles in the cover-up.

Axel’s conviction is overturned, and though he hesitates to leave prison, feeling his time there had given him purpose, he is finally released.

In the closing scenes, on New Year’s night, the community gathers at Crow Point. Around the fire ring, Henry Meloux leads a prayer of healing and welcome.

Axel—Zoongide’e-makwa, “Brave Bear”—is embraced by his family and friends. Moonbeam, his daughter, struggles with the truth about her lineage but finds comfort in his forgiveness.

The O’Connors and the Bosheys share food, laughter, and renewal, symbolizing the restoration of balance. The circle closes not on vengeance but on compassion, as Aurora’s residents choose to honor truth and begin again.

Apostles Cove concludes as a meditation on the long road to redemption—how one act of mercy, truthfully faced, can free generations from the shadows of the past.

Characters

Cork O’Connor

Cork O’Connor, the central figure in Apostles Cove, embodies the tension between justice, heritage, and moral complexity. Once a sheriff of Tamarack County, Cork is introduced as a man aging into reflection, burdened by years of service and mistakes that refuse to fade.

His moral compass is strong but weathered, and the revelation that Axel Boshey—a man he sent to prison—might be innocent unsettles him deeply. This internal conflict fuels his journey not only to revisit an old case but also to confront his role in perpetuating systemic prejudice and personal bias.

Throughout the narrative, Cork’s mixed Ojibwe and Irish heritage serves as both a source of wisdom and alienation, positioning him as a bridge between cultures and communities. His relationships—with his wife Jo, his friend Sam Winter Moon, and his children—anchor him to empathy and humanity, even as his investigations lead him through moral darkness.

Ultimately, Cork’s pursuit of truth transforms from a professional duty into an act of redemption, reinforcing his identity as a seeker of justice in both legal and spiritual senses.

Jo O’Connor

Jo O’Connor represents intellect, compassion, and quiet resilience within the novel’s emotional core. As an attorney and Cork’s wife, she serves as both a moral counterweight and a voice of reason.

Her belief in Axel Boshey’s humanity, despite damning evidence, reveals her deep faith in redemption and her refusal to accept prejudice as truth. Jo’s relationship with Cork is tender but marked by tension—rooted in their shared commitment to justice, yet tested by the strain of moral dilemmas.

Her empathy toward the Ojibwe community and her understanding of family law allow her to bridge cultural divides, particularly when helping Patsy Boshey retain custody of her grandchildren. Beyond her legal acumen, Jo’s role in the narrative underscores themes of maternal protection and moral clarity.

She sees beyond appearances, challenging Cork to question his assumptions and grounding the story in the strength of ethical conviction.

Axel Boshey

Axel Boshey’s character is one of tragic complexity and misunderstood virtue. Initially depicted as the prime suspect in his wife’s murder, Axel carries the burden of alcoholism, shame, and racial prejudice.

His life spirals between acts of love and moments of self-destruction, and his inability to remember the night of the murder casts him as both victim and scapegoat. His eventual confession—driven by a misguided sense of protection toward Bernadette Polaski—reveals a man defined by loyalty and guilt rather than malice.

Years in prison transform Axel into a figure of quiet grace and spiritual renewal. His acceptance of imprisonment as purpose, and his eventual release into forgiveness, make him a symbol of endurance and faith.

In the end, Axel’s strength lies not in vindication but in his willingness to forgive those who wronged him, embodying the redemptive power at the heart of Apostles Cove.

Aphrodite McGill

Aphrodite McGill stands as the dark center of the narrative—seductive, manipulative, and deeply broken. She is both mother and destroyer, whose influence extends far beyond her daughter’s death.

The owner of Shangri-La, a place tinged with decadence and corruption, Aphrodite weaponizes beauty and sexuality to control those around her. Her relationships—with men like Wild Bill Gunderson and her daughter’s husbands—are marked by exploitation and deceit.

Yet beneath her vanity and cruelty lies a hollow longing for love and power, distorted by trauma and moral decay. Her ultimate exposure as Chastity’s killer unmasks her not just as a murderer but as the embodiment of generational corruption.

Through Aphrodite, the novel explores how abuse, control, and secrecy can fester across families and communities, making her both villain and tragic warning.

Chastity Boshey

Chastity Boshey, though deceased for most of the story, haunts its every page as a victim of violence and generational sin. Her life, marked by cycles of abuse and poor choices, mirrors the scars of her mother’s manipulation.

Despite her flaws—drug use, marital conflict, and emotional instability—Chastity’s love for her children and her desire to protect them from Aphrodite’s influence reveal her humanity. Her murder becomes the catalyst for exposing years of buried secrets, turning her into a tragic martyr of inherited trauma.

In Apostles Cove, Chastity is less a passive victim than a symbol of innocence corrupted and courage denied, representing the consequences of silence in the face of familial abuse.

Sam Winter Moon

Sam Winter Moon serves as Cork’s moral anchor and spiritual guide, a figure who embodies Ojibwe wisdom and balance. Calm, intuitive, and grounded, Sam reminds Cork to “listen to the owl”—to seek truth beyond surface evidence and to respect the spiritual undercurrents of life.

His presence bridges the cultural gap between law enforcement’s rationalism and the Ojibwe community’s holistic worldview. Sam’s philosophy of patience and humility contrasts sharply with the chaos of the murder investigation, offering Cork a path toward understanding rather than judgment.

Through him, the novel celebrates Indigenous spirituality as a force of resilience and guidance, anchoring the human struggle within the broader rhythm of nature and spirit.

Patsy Boshey

Patsy Boshey represents unwavering maternal strength and quiet suffering. As Axel’s mother and caretaker to his children, she embodies dignity amid prejudice and hardship.

Living on the Iron Lake Ojibwe Reservation, she confronts systemic mistrust with grace, protecting her family while maintaining faith in her son’s innocence. Her interactions with Cork and Jo highlight the tension between Native traditions and the white legal system, and her insistence on family unity reflects the novel’s recurring theme of kinship as sacred.

In her steadfastness, Patsy becomes a pillar of endurance, illustrating how love and cultural identity can survive injustice.

Henry Meloux

Henry Meloux, the elderly Mide spiritual leader, serves as the novel’s spiritual conscience. His wisdom transcends law and logic, offering guidance rooted in ancestral connection and moral reflection.

Meloux’s counsel to Cork and others often takes the form of parables and silences, forcing them to seek truth within themselves. He embodies forgiveness, patience, and the belief that every soul carries both light and shadow.

In Apostles Cove, Meloux’s teachings help transform pain into purpose, grounding the story’s resolution in a philosophy of reconciliation rather than vengeance.

Lucy Martinelli (Magdalene)

Lucy Martinelli’s character embodies trauma, guilt, and fractured identity. Once thought dead, she reemerges as “Magdalene,” a woman haunted by repressed memories of abuse and violence.

Her descent into instability mirrors the moral corruption of those who wronged her, while her eventual confrontation with Wild Bill and Rocky exposes the tangled web of deceit surrounding Chastity’s death. Lucy’s journey—from victim to survivor—reveals the enduring cost of silence and the healing power of truth.

Her act of self-defense against Aphrodite brings both closure and catharsis, turning her suffering into a painful redemption.

Wild Bill Gunderson and Rocky Martinelli

Wild Bill Gunderson and Rocky Martinelli personify corruption, cowardice, and the toxic masculinity that festers beneath small-town respectability. Wild Bill, domineering and cruel, exploits women and manipulates others into preserving his secrets.

Rocky, his accomplice and Aphrodite’s lover, epitomizes moral weakness—willing to cover up murder to save himself. Their actions, rooted in selfishness and deceit, catalyze decades of injustice.

In the novel’s conclusion, their exposure not only redeems the innocent but also restores a moral balance long disrupted by lies.

Stephen O’Connor

Stephen O’Connor, Cork’s son, represents the continuity of justice and compassion in a new era. His work with the Great North Innocence Project rekindles the investigation, symbolizing hope that truth can survive time and corruption.

Stephen’s empathy and intelligence contrast with Cork’s weariness, suggesting that the next generation inherits not just the burden of justice but the wisdom to pursue it differently. Alongside characters like Sunny Boshey and Moonbeam, Stephen’s presence affirms the novel’s final message—that forgiveness, truth, and community can heal even the deepest wounds.

Themes

Justice and Moral Responsibility

Throughout Apostles Cove, the notion of justice extends beyond the courtroom or legal statutes and into the realm of moral accountability. Cork O’Connor’s involvement in reopening the decades-old Boshey case forces him to confront the consequences of decisions made under imperfect knowledge and the ways institutional prejudice shapes outcomes.

The early conviction of Axel Boshey illustrates how small-town law enforcement, clouded by racial bias and urgency to find closure, can distort truth into a convenient narrative. As Cork reexamines the case years later, the line between justice and retribution becomes uncertain.

The story insists that true justice requires introspection, humility, and a willingness to admit failure. Cork’s moral awakening lies not only in seeking freedom for an innocent man but also in facing his own role in perpetuating systemic injustice.

The novel positions justice as an evolving process—one that must reconcile law with empathy, evidence with conscience, and personal duty with community healing. By the end, when Axel’s innocence is proven and forgiveness prevails, Krueger presents justice not as the triumph of law but as a restoration of moral balance and human dignity.

Prejudice and Cultural Division

The book exposes the deep social rifts between Native and white residents of Aurora and the surrounding Ojibwe communities. These divisions are not merely external conflicts; they infect personal relationships, police investigations, and even family structures.

Axel Boshey’s wrongful conviction demonstrates how suspicion often follows the marginalized, regardless of evidence. Cork, who is part Ojibwe himself, exists between two worlds, constantly negotiating identity and belonging.

His dual heritage gives him insight into both sides but also subjects him to skepticism from each. The novel uses this cultural tension to critique the blindness of institutions that dismiss Indigenous voices and treat Native communities as peripheral to justice.

Yet, it also acknowledges the internal fractures within the Ojibwe community, where shame, loyalty, and survival often silence truth. Through these depictions, the story insists that reconciliation cannot occur without honesty about historical injustice and shared humanity.

The cultural divide becomes a moral landscape that each character must navigate, revealing how ignorance and prejudice erode trust, while understanding and respect offer the only path toward collective healing.

Family, Love, and Betrayal

Family in Apostles Cove is both sanctuary and battlefield. The Boshey and McGill families embody generations of trauma and secrecy, where love is often twisted by control, shame, and unspoken pain.

Aphrodite McGill’s exploitation of those closest to her—her daughter, lovers, and even grandchildren—represents how power and desire can corrupt the very structure meant to nurture. In contrast, Cork’s family life offers a counterpoint of imperfect but genuine affection, built on mutual respect and forgiveness.

The novel examines how family bonds can perpetuate cycles of abuse and silence but also serve as catalysts for redemption. Axel’s willingness to sacrifice his own freedom to protect Bernadette and her unborn child exemplifies the moral extremes love can drive.

The eventual reunion of Axel with his children underlines Krueger’s belief that forgiveness, though painful, is the only true closure. Family is shown not as an immutable blood tie but as a chosen act of endurance and compassion, one that requires confronting buried truths rather than escaping them.

Truth and Perception

The pursuit of truth is the emotional and structural core of Apostles Cove. What begins as a reopened murder investigation becomes a meditation on how truth is constructed, manipulated, and concealed.

Each witness, from Aphrodite to Bernadette to Cork himself, presents fragments colored by fear, guilt, and memory. The revelation that the wrong man has spent decades in prison underscores how easily perception replaces fact when emotion or bias dominates.

Cork’s journey mirrors that of the reader—moving from certainty to doubt, from judgment to understanding. Krueger portrays truth not as a single revelation but as a mosaic assembled through courage, patience, and the willingness to question one’s assumptions.

The story demonstrates how truth has moral gravity: when suppressed, it festers and destroys; when revealed, it heals and restores. In the end, uncovering what truly happened to Chastity Boshey becomes less about solving a crime and more about reclaiming the integrity lost to lies and fear.

Redemption and Forgiveness

Forgiveness forms the emotional resolution of Apostles Cove, tying together its themes of justice, family, and truth. Axel Boshey’s imprisonment becomes an unlikely crucible for transformation.

Instead of emerging embittered, he discovers purpose in guiding other inmates, embodying a spiritual freedom that contrasts with his physical confinement. His ultimate release is not portrayed as triumph but as the quiet culmination of inner grace.

Similarly, Cork must forgive himself for the mistakes of youth and the failures of his profession. The closing scenes, with the community gathered around the fire at Crow Point, signify a collective act of healing.

The ritual smudging led by Henry Meloux symbolizes purification through acceptance rather than denial of the past. Forgiveness here is not erasure—it is acknowledgment.

It demands remembering pain without letting it define the future. Krueger uses this theme to affirm the possibility of moral renewal even in lives scarred by violence and loss, suggesting that redemption, though hard-won, remains the highest form of justice.