Are You Mad at Me Summary and Analysis

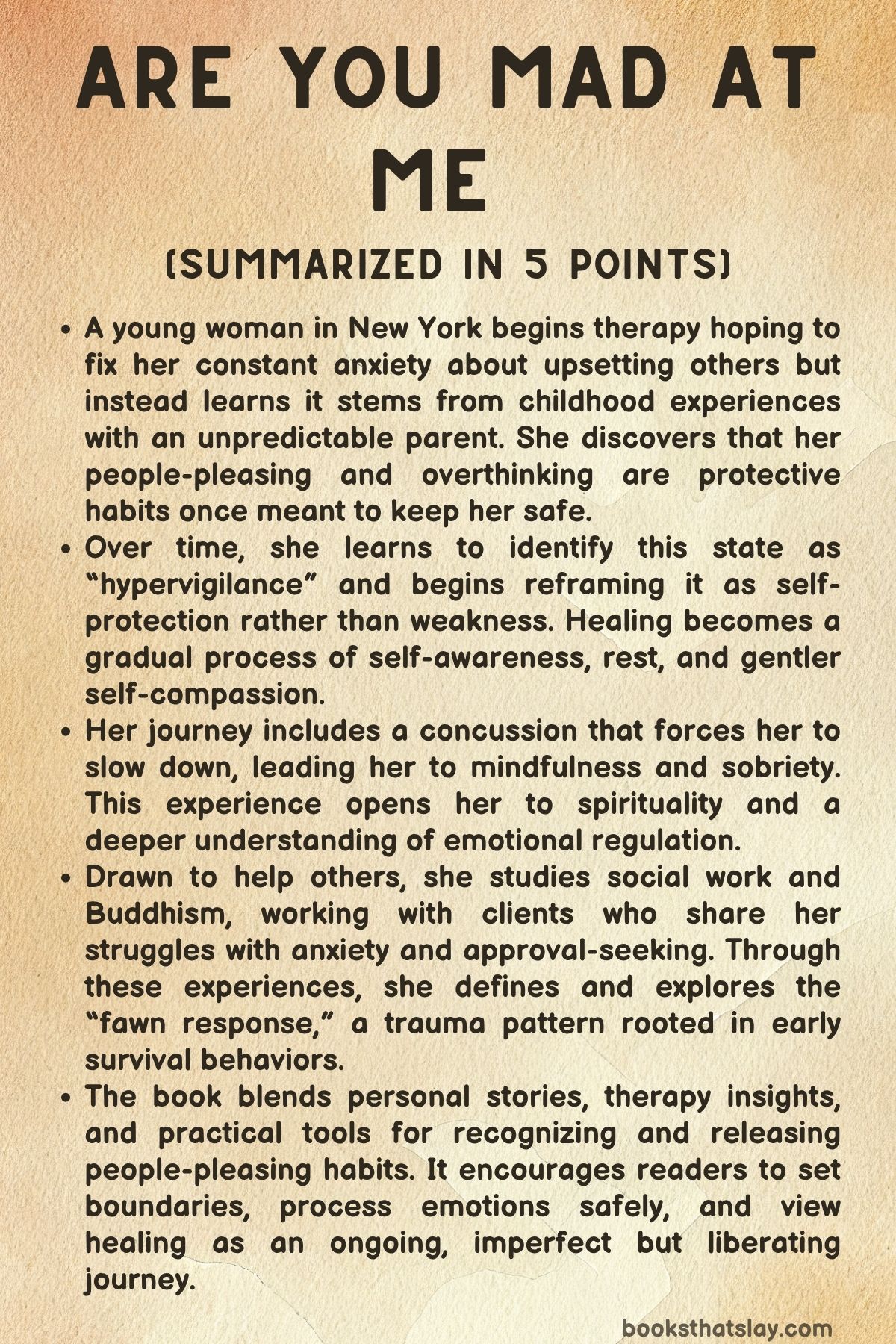

Are You Mad at Me by Meg Josephson is a compassionate exploration of anxiety, trauma, and the lifelong process of unlearning the urge to please others. Blending memoir, psychology, and gentle self-inquiry, Josephson traces her own evolution from a hypervigilant child of an alcoholic parent to a therapist and writer helping others navigate similar fears.

The book offers insight into the “fawn response,” a lesser-known trauma reaction that manifests as appeasement and people-pleasing. Through personal stories, client vignettes, and practical guidance, Josephson reframes healing not as a final destination but as a continuous act of self-understanding, boundary-setting, and compassionate awareness.

Summary

The story begins with a young woman—twenty years old, living in New York City—who starts therapy in search of a quick fix for her constant anxiety that others might be angry with her. Her therapist, instead of offering surface-level reassurance, encourages her to look backward, into the chaos of her childhood with an alcoholic and volatile father.

Through these sessions, she recognizes that her adult tendencies—anticipating criticism, overanalyzing messages, and fearing conflict—are not random flaws but the lingering habits of vigilance that once kept her safe. She names this constant alertness “hypervigilance” and gradually accepts that healing means learning to live with imperfection rather than erasing discomfort altogether.

A concussion during college becomes an unexpected turning point. Forced into stillness, she abandons her coping mechanisms and slowly discovers meditation and spirituality.

These practices expand her tolerance for quiet and help her see that rest and reflection are necessary for growth. Over time, she stops drinking, embraces sobriety, and channels her healing into helping others.

After earning her master’s in social work from Columbia University and studying Buddhism, she becomes a therapist whose clients often mirror her own earlier struggles—fear of disapproval, anxiety, and chronic self-blame. When one client describes ruminating over perceived social mistakes, she shares a short video reminding people that they are safe and not inherently “bad.

” The clip goes viral, encouraging her to continue speaking publicly about these issues and ultimately leading to the creation of Are You Mad at Me.

The central idea of the book lies in unpacking the “fawn response,” a survival mechanism first defined by therapist Pete Walker. Unlike fight, flight, or freeze, fawning involves moving toward threat through appeasement—seeking safety by pleasing others.

Josephson explains that this behavior often forms in childhood environments where love or safety depend on compliance and calm. It can persist into adulthood as chronic self-erasure, showing up as overapology, indecision, boundarylessness, and the desperate desire to maintain peace.

She stresses that these behaviors are not weaknesses but protective strategies that once made sense. Healing begins when individuals recognize that what once ensured survival may now be unnecessary.

To illustrate, Josephson introduces a range of composite clients who represent different ways the fawn response can manifest. Brianna, the Peacekeeper, grows up tiptoeing around her mother’s moods, later avoiding all conflict as an adult.

Theo, the Performer, learns to be funny and upbeat to deflect tension but becomes exhausted by always needing to keep everyone happy. Sophie, the Caretaker, is parentified young and becomes self-sufficient to the point of isolation.

Alicia, the Lone Wolf, hides her needs entirely to avoid burdening others. Carter, the Perfectionist, pursues flawless achievement to dodge criticism.

Rachel and Lucy, the Chameleons, shapeshift to belong—one to escape bullying, the other to survive sexual abuse. Through these stories, Josephson shows how diverse experiences can lead to the same underlying behavior: sacrificing authenticity for safety.

She then explores how trauma embeds itself in both body and mind. The nervous system learns to equate hyperalertness with survival.

The brain’s reward circuitry, through dopamine, even reinforces stress, making individuals unconsciously seek familiar chaos. Josephson explains how breathing practices, gentle movement, and mindfulness can gradually teach the body to identify calm as safe.

Her suggested exercises—lengthened exhalation, sensory grounding, humming, stretching—help retrain the nervous system to rest without fear. Healing, she reminds readers, happens through repetition and patience rather than sudden transformation.

Josephson connects individual pain to larger social patterns. Systems of oppression—gender expectations, racism, ableism, classism—often reward compliance and penalize assertiveness, particularly for women and marginalized people.

She acknowledges that for some, fawning may remain necessary in unsafe environments, and that healing is not about rejecting all appeasement but discerning when it serves genuine safety versus old conditioning.

A major theme of Are You Mad at Me is grief—the emotional reckoning with what was lost or never provided. Josephson recounts her mother’s early-onset Alzheimer’s and the sorrow of losing her before she was truly gone.

This personal grief extends to the emotional neglect of her childhood and the realization that her parents, though loving in their own limited ways, could not meet her deeper needs. She defines grief as acknowledging what did not exist—nurture, stability, emotional safety—before moving toward acceptance.

This process repeats across life: mourning who our parents were not, who we once were, and who we hoped others could become.

She discusses anger as a necessary part of healing. Many fawners suppress anger to preserve peace, but Josephson argues that acknowledging anger is essential—it marks the boundary between self and other.

Suppressing it breeds resentment and shame. Allowing it, without destructive expression, reconnects individuals to their sense of worth and values.

In her own life, recognizing her father’s emotional volatility helped her separate her identity from his moods. She learns that gratitude and grief can coexist: one can appreciate what was given while mourning what was missing.

In later sections, Josephson guides readers through mindfulness and emotional regulation. She introduces the NICER method—Notice, Invite, Curiosity, Embrace, Return—as a framework for responding to emotions with compassion rather than control.

Using real examples, she shows how a pause between feeling and reaction creates space for wiser choices. Emotions are reframed as temporary signals rather than threats.

Anger reveals violated values; resentment points to ignored needs; anxiety signals uncertainty. The goal is not to suppress emotion but to hear its message without letting it dominate behavior.

The book also explores the illusion of personalization—the tendency to assume that others’ moods or words are about us. Through case studies, Josephson dismantles this belief, presenting the “Three P’s”: nothing is personal, permanent, or perfect.

She draws on psychological concepts like the spotlight effect, which shows that people notice us far less than we imagine. Letting go of control over others’ perceptions allows for freedom and authenticity.

Conflict, another major topic, is reframed as an essential part of connection rather than proof of failure. Avoidance, she explains, often stems from childhood environments where disagreement equaled danger.

She teaches how to differentiate discomfort from actual threat and how to repair relationships after conflict through honest communication and accountability. Examples include clients learning to express needs directly and couples transforming blame into understanding.

Boundaries, Josephson argues, are acts of love—not walls but bridges that sustain connection without self-sacrifice. She encourages readers to replace reflexive yeses with questions like “Do I have to?” and “Do I want to? ” Boundaries clarify what one can offer without resentment.

They are not tools to control others but commitments to one’s own actions and capacities. Through various vignettes—friends canceling plans honestly, families adjusting expectations, individuals reclaiming time—she shows how truth fosters respect.

The book culminates in rediscovering identity after a lifetime of pleasing others. Fawners often feel they don’t know who they are because their lives have revolved around others’ needs.

Josephson describes learning to trust her intuition, distinguishing it from anxiety, and reconnecting with desires once buried under fear. She offers tools for rebuilding self-trust: spending time alone, journaling, returning to childhood joys, and treating envy as a signal of unacknowledged longing.

The journey of healing, she concludes, is not about erasing the past but living more fully within the present.

In its final message, Are You Mad at Me frames recovery from people-pleasing as both personal and collective. Healing expands our capacity to connect authentically, to set boundaries without guilt, and to extend compassion without losing ourselves.

The book closes with a reminder that progress is nonlinear—regression is part of the process—and that awareness itself is healing. Every time we meet discomfort with gentleness, we rewrite the patterns that once kept us small.

Characters

Meg Josephson

At the center of Are You Mad at Me is the narrator Meg—a 20-year-old woman whose journey from fearful people-pleaser to compassionate therapist anchors the book’s exploration of trauma, healing, and self-awareness. Initially portrayed as anxious and hypervigilant, she begins therapy in New York believing her fear of others’ anger can be quickly “fixed.”

Through her therapist’s guidance, she uncovers that her reactions stem from childhood experiences with an alcoholic and volatile father. The vigilance that once protected her becomes a maladaptive pattern in adulthood—anticipating criticism, overanalyzing messages, and striving for perfection to secure safety.

Her story charts the slow transformation from self-blame to self-understanding. A concussion forces her into stillness, catalyzing her spiritual awakening and eventual sobriety.

As she grows, she integrates mindfulness, grief, and compassion into her life and career, recognizing that healing is not linear but cyclical. By the book’s end, she embodies the principle she teaches: self-compassion is not indulgence but survival, and fawning can be unlearned through awareness and boundary-setting.

Meg’s Father

The narrator’s father is the primary architect of her early trauma. Charismatic in public but volatile and emotionally abusive in private, he instills in his daughter the belief that love must be earned through appeasement.

His unpredictable moods cultivate her hypervigilance—the constant scanning of emotional weather to preempt explosion. He represents the paradox of conditional affection: capable of kindness but emotionally immature and self-focused.

His alcoholism exacerbates instability, while his dependence on the narrator as an adult reveals his inability to separate emotional needs from parental responsibility. The father’s duality—charming yet cruel—becomes the model through which the narrator learns to navigate love as both dangerous and necessary.

Her healing requires acknowledging his harm without erasing the fragments of love that did exist, illustrating the book’s recurring theme of holding multiple truths at once.

Meg’s Mother

The mother is depicted with complexity—both a source of tenderness and an emblem of grief. Early in life, she provides partial warmth yet fails to protect her daughter from the father’s volatility.

Later, her diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s transforms her into a living symbol of loss. The narrator’s grief for her mother unfolds on two levels: mourning the woman she is losing and confronting the mother she never fully had.

The mother’s decline exposes the emotional emptiness of the family dynamic and forces the narrator to redefine love beyond caretaking. Despite the mother’s passivity in moments of crisis, her illness ultimately deepens the narrator’s compassion and capacity for acceptance.

The mother’s presence—then absence—marks the narrator’s transition from seeking external validation to cultivating inner security.

Brianna

Brianna exemplifies the fawn response through her relentless pursuit of harmony. Raised by a mother whose silence and moodiness govern the household, she learns to anticipate conflict and end it through apology or self-erasure.

As an adult, she remains trapped in patterns of avoidance and excessive empathy, mistaking peacekeeping for love. Her character highlights how emotional neglect masquerades as calm and how chronic guilt becomes a substitute for agency.

Brianna’s journey underscores the book’s assertion that self-abandonment, while once protective, ultimately breeds disconnection and resentment.

Theo

Theo’s upbringing in an environment charged with passive aggression molds him into an entertainer who uses humor as armor. His charm and positivity conceal fear of rejection and a deep-seated sense of responsibility for others’ happiness.

The act of constant performance becomes both a shield and a prison. Through Theo, Are You Mad at Me illustrates the exhaustion of emotional labor and the cost of confusing likability with safety.

His story reveals that underneath laughter often lies loneliness, and genuine connection requires relinquishing control over how one is perceived.

Sophie

Sophie’s narrative captures the burden of premature responsibility. As a child tasked with meeting her family’s emotional and practical needs, she is rewarded for her competence but denied the right to vulnerability.

This early parentification leads to adult hyper-independence, emotional fatigue, and resentment masked as resilience. Sophie’s identity is built on usefulness, making dependence feel dangerous.

Her healing begins when she allows herself to be supported and recognizes that self-worth need not hinge on service. Through her, the author explores how overfunctioning can be a trauma response masquerading as strength.

Alicia

Alicia’s emotional neglect teaches her that needing others invites disappointment. She withdraws inward, creating safety through solitude but also fostering isolation.

Her self-sufficiency becomes a barrier against intimacy, while her search for external validation through achievement or admiration reflects an unhealed longing for recognition. Alicia represents the fawner who hides rather than appeases—her silence a different form of self-erasure.

The narrative uses her arc to show that independence, when rooted in fear, is another mask for vulnerability.

Carter

Carter’s story embodies the pressure of conditional love. Growing up in an environment where mistakes are punished and emotions dismissed, she learns that perfection is the only route to acceptance.

Her identity fuses with productivity; she equates worth with output and safety with flawlessness. This relentless striving becomes a socially rewarded form of fawning, celebrated as ambition while concealing terror of failure.

Carter’s healing involves tolerating imperfection and realizing that love, to be real, must survive disappointment. Her journey reflects the author’s own reckoning with achievement as a substitute for belonging.

Rachel

Rachel’s transformation from bullied child to social shapeshifter illustrates the corrosive impact of minimizing one’s identity to fit in. Parental dismissal of her pain teaches her that authenticity risks rejection.

In adulthood, she constantly adapts to others’ preferences, losing contact with her own desires. Rachel’s character shows how chronic conformity—though superficially adaptive—creates profound inner emptiness.

Her struggle underscores the book’s recurring theme: safety pursued through invisibility results in self-loss. Healing for Rachel means reclaiming visibility and learning that authenticity, not acceptance, is the true antidote to shame.

Lucy

Lucy’s fawning originates from trauma of a far more severe kind—sexual abuse by her stepfather. Her appeasement during abuse is a survival tactic that later morphs into guilt and misplaced self-blame.

Lucy’s narrative is perhaps the book’s most harrowing and redemptive: it dismantles the myth that compliance equals consent and reframes fawning as a brilliant but time-limited survival strategy. Her eventual confrontation of self-blame models the process of transforming trauma from silent endurance to conscious reclamation.

Lucy embodies the book’s deepest message—that understanding the origin of fawning is the first step toward forgiveness of self.

Will

Will appears as a secondary yet symbolic figure, representing the high-functioning perfectionist whose inner urgency masks unresolved childhood fear. His story demonstrates how trauma manifests not only in despair but in overdrive—through constant motion, unrealistic goals, and self-criticism disguised as discipline.

Guided toward micro-practices and incremental healing, Will learns to value “1 percent better” over instant transformation. His evolution mirrors the narrator’s teaching philosophy: regulation over revolution, compassion over control.

Evelyn

Evelyn’s avoidance of conflict exposes the quiet loneliness of chronic appeasement. By keeping people at a distance to prevent discomfort, she sacrifices authenticity and intimacy.

Her realization that avoidance breeds isolation encapsulates the book’s broader argument that discomfort is not danger. Evelyn’s journey toward tolerating confrontation marks the turning point where fear gives way to trust—in herself and in others’ capacity to handle truth.

Stacy

Stacy’s boundary struggle during her brother Ethan’s financial crisis exemplifies how old family roles persist into adulthood. Her automatic rescue response, followed by anger and guilt, reveals the tug-of-war between compassion and self-preservation.

Stacy’s eventual boundary-setting—offering support within limits—models mature relational healing. Her story illustrates that boundaries are not walls but commitments to sustainability, proving that love can coexist with limitation.

Alex

Alex’s longing for her father’s apology encapsulates one of the book’s most poignant insights: that closure from others is often unattainable. Her waiting mirrors the narrator’s own early dependence on external validation.

Through Alex, the narrative teaches that healing involves “changing your relationship to the relationship,” accepting loss without relinquishing dignity. Alex becomes a vessel for the reader’s understanding that self-validation is the final stage of grief.

Themes

Hypervigilance and the Legacy of Fear

In Are You Mad at Me, Meg Josephson portrays hypervigilance as both a symptom and a survival strategy born from instability. The narrator’s early life with an alcoholic and volatile father imprints a deep sense of alertness, where safety depends on anticipating others’ moods.

This state of constant watchfulness seeps into adulthood, coloring professional and personal interactions alike. The book shows how such vigilance—once protective—becomes maladaptive when carried into safe environments, manifesting as anxiety, overthinking, and the relentless pursuit of reassurance.

Josephson frames hypervigilance not as a flaw to be eradicated but as an intelligent adaptation that deserves compassion and understanding. Healing, in this light, means recognizing that the threat no longer exists and teaching the body to stop bracing for impact.

The author’s insight into the mind-body connection—how shallow breathing and muscle tension reinforce perceived danger—transforms hypervigilance from a purely psychological concept into a physiological loop that can be disrupted through conscious practice. The narrative’s honesty about relapse, exhaustion, and gradual progress illustrates that recovery is not a single epiphany but a reconditioning of the nervous system through repetition and care.

Ultimately, hypervigilance evolves from a symbol of fear into one of resilience, showing how awareness can transform old defenses into sources of wisdom.

The Fawn Response and the Quest for Safety

Josephson introduces the “fawn response” as a pivotal theme that reframes people-pleasing as a survival tactic rather than a personality defect. The fawn response—moving toward threat by appeasing it—arises from early environments where love and safety were conditional.

The book’s many case studies, from Brianna the Peacekeeper to Carter the Perfectionist, reveal how children learn to manage chaos by being useful, agreeable, or invisible. These patterns, rewarded by both family and society, mature into adulthood as chronic self-sacrifice and boundarylessness.

What makes this theme particularly compelling is Josephson’s insistence that the fawn response cannot simply be “unlearned” through willpower; it must be replaced with new, safer experiences that teach the body it can survive displeasure. She underscores how systemic pressures—gender expectations, racism, ableism—can reinforce fawning as a necessary social armor.

Through this lens, self-compassion becomes a political and spiritual act. By identifying fawning as an embodied response rather than a moral failure, Josephson dismantles shame and offers readers permission to reclaim their agency.

The theme’s progression—from identifying the behavior to understanding its origin, and finally, to transforming it—forms the backbone of the book’s emotional journey toward authentic selfhood.

Grief, Acceptance, and the Complexity of Love

Grief in Are You Mad at Me is portrayed not only as mourning the dead but as reckoning with the living—parents who could not provide safety, relationships that failed to nurture, and fantasies of love that never materialized. Josephson describes grief as the acknowledgment of absence: the realization that certain emotional needs went unmet, and that no amount of perfectionism or caretaking can retroactively fulfill them.

Her mother’s early-onset Alzheimer’s becomes a powerful metaphor for ambiguous loss—the pain of losing connection while the person still exists. The narrator’s grief deepens into a recognition that acceptance does not erase pain but coexists with it.

Josephson’s refusal to vilify her parents is vital; she insists that love and harm can coexist, that gratitude for what was given can stand alongside sorrow for what was not. This nuanced understanding dismantles black-and-white thinking and invites readers to approach their pasts with both truth and tenderness.

By presenting grief as a recurring companion—returning across life stages—she normalizes its persistence and reframes it as an ongoing dialogue rather than a closed chapter. In doing so, grief becomes not only a vehicle for healing but also a portal to self-compassion and emotional maturity.

Boundaries as Self-Honoring

Boundaries emerge as a radical expression of self-respect and sustainability in Josephson’s narrative. She rejects the popular notion of boundaries as defensive walls, instead presenting them as bridges that preserve connection without self-betrayal.

For survivors of fawning and hypervigilance, setting limits feels like a violation of their survival code; saying “no” threatens the illusion of safety built through compliance. Through stories of characters like Stacy, who must renegotiate her role as the family rescuer, and Lauren, who learns that reduced contact is not rejection but capacity, Josephson reveals how boundaries reorient one’s life around authenticity rather than obligation.

Her framing of boundaries as “self-honoring” reframes them from acts of withdrawal to acts of truth. They are not about controlling others but about clarifying what one will and won’t participate in.

The book’s emphasis on consistency—maintaining limits even amid guilt and resistance—illustrates that safety is built through repetition, not perfection. This theme resonates beyond individual psychology; it challenges cultural scripts that equate goodness with self-erasure.

By reclaiming the right to rest, to say no, and to prioritize emotional bandwidth, Josephson argues that boundaries are not barriers to love but the soil in which real connection grows.

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Emotional Regulation

Throughout Are You Mad at Me, mindfulness operates as both method and philosophy. The NICER framework—Notice, Invite, Curiosity, Embrace, Return—embodies the gentle persistence Josephson advocates for emotional healing.

Rather than suppressing feelings, she teaches readers to observe them as temporary messages. This approach transforms anxiety, anger, and guilt from enemies into guides.

The emphasis on physiological practices such as diaphragmatic breathing, sensory grounding, and nervous-system regulation anchors emotional insight in the body, dissolving the false divide between mind and flesh. Josephson’s exploration of mindfulness is not detached or esoteric; it grows from lived necessity, from years of overthinking and control-seeking that failed to deliver peace.

By recognizing that worry offers only an illusion of control, she encourages surrender—not in defeat but in presence. Self-compassion, framed as the antidote to the inner critic, reclaims the same tenderness once denied in childhood.

This theme culminates in the realization that peace is not the absence of discomfort but the capacity to stay with it without self-abandonment. In this way, mindfulness becomes an act of self-trust, a return to one’s body and breath as reliable sources of safety.

Intergenerational Trauma and Healing Through Awareness

Josephson’s discussion of intergenerational trauma widens the scope of personal healing to encompass lineage and collective experience. She shows how trauma is transmitted not only through behavior but also through biology—altered stress responses, inherited vigilance, and the unspoken rules of survival passed down through generations.

Her references to research on epigenetic changes in descendants of trauma survivors anchor this idea in science while maintaining emotional accessibility. The narrative recognizes that inherited pain can manifest as perfectionism, overachievement, or fear of rest—echoes of ancestors who equated safety with control.

Yet the book is ultimately hopeful: it asserts that awareness interrupts repetition. By naming these patterns and creating new choices, individuals contribute to generational repair.

Josephson’s assertion that “each generation heals what it can” offers both grace and realism, acknowledging that progress, not completion, is the goal. This theme extends healing beyond the self, suggesting that personal transformation ripples outward, softening the collective nervous system of families and communities.

In linking the personal to the generational, Josephson situates healing as both a private reclamation and a form of quiet revolution.