At Dark, I Become Loathsome Summary, Characters and Themes

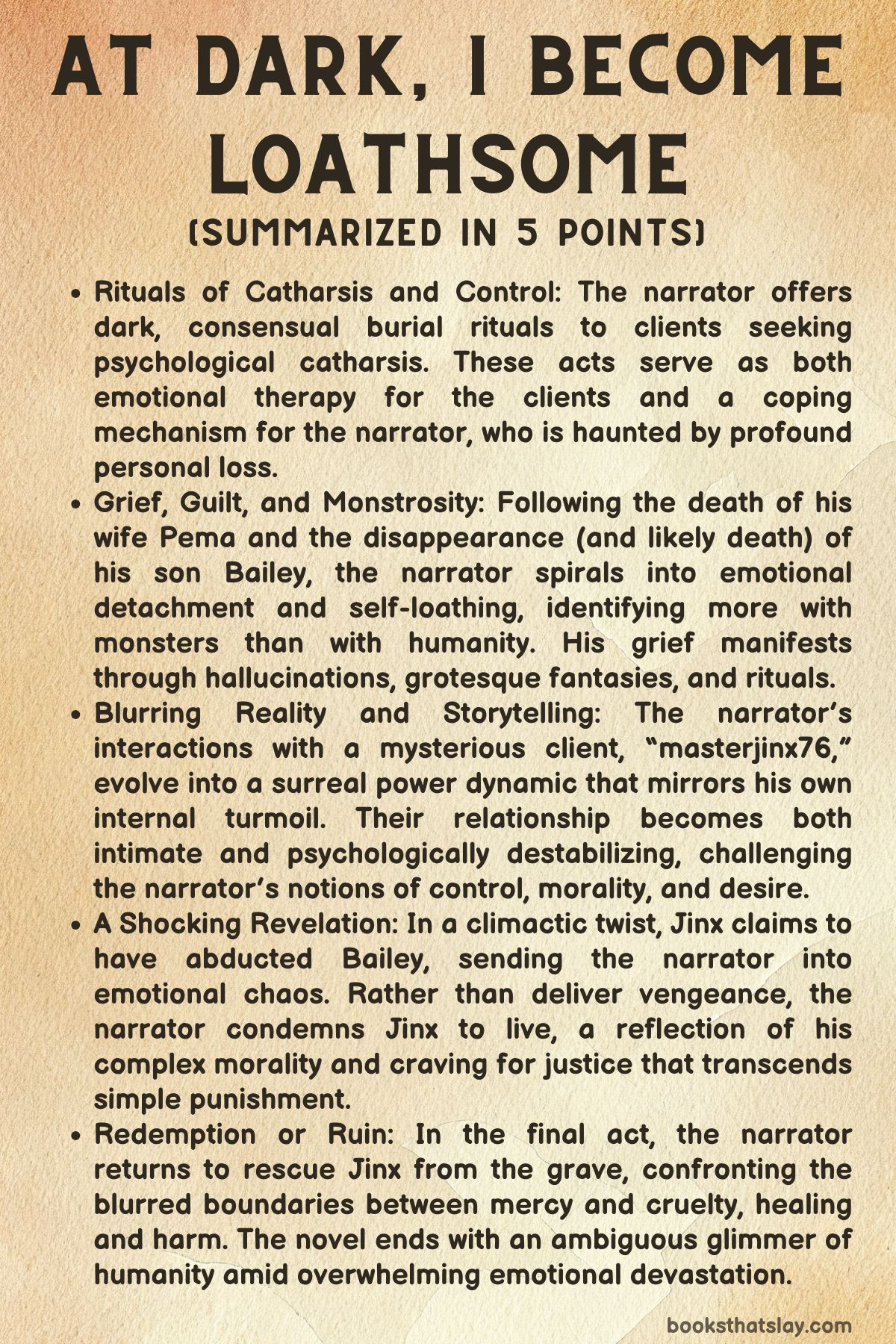

At Dark I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca is a psychological horror novel that explores the limits of grief, trauma, and identity through a deeply disturbed narrator whose life has unraveled in the wake of loss. The novel blurs the boundary between ritual and cruelty, therapy and violence, redemption and perversion.

It examines how grief, untreated and unspoken, can corrode a person’s humanity. Through the interlinked stories of Ashley Lutin, a grief-stricken father who stages live-burial “rituals” for suicidal clients, and Keane Withers, a young addict caught in a sexual blackmail scheme, LaRocca constructs a chilling portrait of how people cope—often destructively—with their own suffering and the suffering of others.

Summary

Ashley Lutin is a tormented man who conducts elaborate nighttime rituals where he buries clients alive in coffins for thirty minutes, simulating death to supposedly grant them emotional release. These rituals are secretive and symbolic, conducted in darkness and with the belief that facing death will lead to transformation.

But for Ashley, the process is deeply personal—each burial chips away at his own stability, stirring memories of the two tragedies that define him: the death of his wife, Pema, from cancer, and the disappearance of his young son, Bailey. These events have left Ashley emotionally fractured, his physical appearance distorted by piercings and implants, serving both as a form of penance and a barrier between himself and the world.

The narrative shifts fluidly between Ashley’s rituals, his deteriorating mental state, and reflections on his loss. One client, a woman who undergoes a simulated burial, emerges emotionally overwhelmed and grateful, but Ashley remains emotionally distant.

He follows a ritual guidebook that includes rules for “aftercare,” a process meant to help both client and caregiver emotionally recover. Ashley, however, struggles with this part of the work.

While he longs for connection, he finds empathy painful, even threatening, and views his rituals as acts of service mixed with dominance and detachment.

Ashley’s trauma resurfaces frequently in the form of hallucinations. He sees his dead wife in the kitchen and envisions Bailey in their backyard wearing Pema’s wedding dress.

These visions accuse him of internalized shame—particularly over Bailey’s queerness and Ashley’s discomfort with it. Ashley’s relationship with Bailey was marked by confusion and distance, especially when Bailey began expressing gender fluidity.

Pema’s ghostly presence chastises Ashley for failing to support their son and for hiding behind his own unresolved shame.

As Ashley is contacted by a new client—username “masterjinx76,” later revealed to be a man named Jinx—the story’s emotional and psychological stakes increase. Jinx is unlike the others: confident, beautiful, and emotionally probing.

Their meeting takes place in a candlelit, graffiti-covered schoolhouse, a space that feels haunted by both memory and possibility. Jinx challenges Ashley’s authority and draws him into a disarming emotional exchange.

He forces Ashley to eat a marble to prove his sincerity, then initiates a conversation that becomes confessional and provocative. Ashley, shaken, begins to unravel further.

He is captivated by Jinx’s vulnerability and power, his presence echoing both Ashley’s son and an idealized version of himself.

The ritual between Ashley and Jinx takes a turn when Jinx claims he once knew and harmed Bailey. Ashley, torn between grief and rage, digs Jinx up from the shallow grave mid-ritual, desperate for clarity.

Jinx offers cryptic answers, hinting at abuse, imprisonment, and even the burning of Bailey’s remains. As Jinx provokes and teases, Ashley’s desire for revenge escalates.

He considers killing Jinx with a hammer, pushed by the possibility that this man may have murdered his child.

But just as violence seems inevitable, the ghostly figure of Bailey appears at the schoolhouse. His silent presence halts Ashley in his tracks.

In this moment of reckoning, Ashley gives Bailey a drawing and sends him off into the night, whispering a plea for peace. The act is symbolic—perhaps Bailey is not alive, but Ashley recognizes the destructive path he is on.

The gesture is one of release, though it comes too late to absolve him.

The narrative also includes a parallel story of Keane Withers, a young meth addict manipulated into seducing and murdering a porn actor named Mace Cavalier. Keane, toothless and desperate, is drawn into the world of Dubois, a sadistic voyeur who orchestrates and records the encounter for his own gratification.

After Keane kills Mace in a moment of panic, he is trapped in a surveillance-filled room with the body and slowly loses his sanity. He begins to eat parts of Mace’s corpse and believes he is hunting for a “spider in the brain,” a metaphor for the psychological infestation that has consumed him.

Eventually, it is suggested that Ashley himself is the narrator of Keane’s story, aroused and inspired by the horror. He decides to begin performing lethal rituals under the guise of therapy, seeing himself as a savior even as he buries an elderly woman alive.

When guilt pushes him to unearth her body later, it’s too late—she is dead. Cradling her in despair, Ashley whispers “Happy birthday,” the same phrase once used for Bailey.

The repetition underscores his inability to distinguish between love, loss, and destruction.

As the story progresses toward its final stages, Ashley becomes increasingly untethered. In his mind, these rituals are no longer symbolic—they are acts of salvation, acts that bring people “peace.”

Yet each burial, each death, draws him further into moral collapse. The emotional ambiguity at the heart of the novel—whether Ashley is driven by grief, guilt, compassion, or cruelty—remains unresolved.

His actions are steeped in ritual and language of care, but result in real suffering and irreversible harm.

In the closing chapters, Ashley revisits the site where he buried the elderly woman and returns to the schoolhouse where his final confrontation with Jinx took place. The schoolhouse, like Ashley, is decaying—a structure once intended for learning, now reduced to shadows and dust.

With nothing left to lose, Ashley attempts to understand what redemption might mean, if it is possible at all. But the novel offers no easy absolution.

Instead, it leaves Ashley in the space between intention and consequence, between imagined mercy and actual violence.

At Dark I Become Loathsome is ultimately about the grotesque ways grief reshapes identity. Ashley’s journey is not about healing, but about witnessing the transformation of sorrow into something monstrous.

It’s a slow undoing, and every ritual, memory, and hallucination deepens his descent into emotional ruin. The novel forces readers to question whether Ashley is a man performing acts of salvation or enacting his own suffering onto others under the guise of help.

The line between empathy and horror is blurred, and in Ashley’s world, even love becomes indistinguishable from harm.

Characters

Ashley Lutin

Ashley Lutin is the anguished, morally ambiguous heart of At Dark I Become Loathsome, a man whose very name evokes decay and emotional rot. His identity is rooted in trauma, loss, and self-loathing, which manifests in both his physical appearance and his chosen rituals of simulated death.

Once a husband and father, Ashley is now unrecognizable from the man he once was—his grotesque body modified with piercings and surgical implants serves not only as a form of self-punishment but also as a warning to the world to keep away. Haunted by the death of his wife, Pema, and the disappearance of his son, Bailey, Ashley seeks solace and meaning in orchestrating faux-burial ceremonies that mimic death to inspire rebirth in his clients.

Yet even these compassionate façades are tinged with cruelty, control, and unresolved grief. Ashley’s sense of self disintegrates further as he begins to internalize the ideologies he once kept at bay—ideas that sanctify pain and elevate death to a holy act.

His descent is not only psychological but spiritual, a complete unraveling of identity where boundaries between savior and destroyer dissolve. Through encounters with characters like Jinx and Tandy, Ashley confronts his own suppressed queerness, the shame he harbored toward Bailey’s identity, and his fear of emotional vulnerability.

Despite brief moments of tenderness and introspection, he increasingly fails to distinguish healing from harm, and compassion from coercion. By the novel’s climax, Ashley has become a paradox—both executioner and mourner, victim and perpetrator—forever suspended in the shadow of his own loathsome transformation.

Bailey Lutin

Bailey, though physically absent for most of the narrative, occupies a persistent and aching presence in Ashley’s psyche. Once a vibrant child with a growing awareness of his gender identity, Bailey’s queerness became a mirror in which Ashley saw his own unresolved fears and failures.

His memory haunts every interaction Ashley has—especially those involving intimacy, shame, and self-hatred. Visions of Bailey in a wedding gown or as a ghost silently witnessing his father’s cruelty underscore the weight of regret Ashley carries.

The novel suggests that Bailey was abducted, abused, and possibly murdered, revelations that violently puncture any illusions Ashley might have had about closure or redemption. Bailey represents both innocence and judgment, a spectral echo of a love that Ashley failed to protect.

His reappearance in spectral form during Ashley’s confrontation with Jinx becomes a pivotal moment of spiritual reckoning, where revenge gives way to grief. Bailey’s memory drives Ashley toward madness, yet also anchors his fleeting attempts at atonement.

The tragedy of Bailey is compounded by the narrator’s complicity—through past neglect, misunderstanding, and later, through his destructive attempts at healing others that echo his failure to save his son. Bailey is thus both a lost child and a silent moral compass, reminding Ashley—and the reader—that unresolved pain can birth monstrous acts when left to rot in silence.

Pema Lutin

Pema, Ashley’s deceased wife, embodies the ghost of emotional stability and maternal warmth, now lost to the encroaching rot of grief. Her death from cancer devastated Ashley and initiated his plunge into self-destruction and ritual obsession.

Though she appears only in hallucinations, her voice is one of clarity, often serving as Ashley’s conscience. She confronts him with uncomfortable truths—especially about his internalized homophobia and failure as a partner and parent.

Her memory is intricately tied to domestic scenes—cooking in the kitchen, glimpsed in the yard—reflecting Ashley’s yearning for the ordinary life he once had. Yet even these recollections are not purely sentimental.

They are accusatory, imbued with pain, frustration, and judgment. In many ways, Pema’s specter is as complex as Ashley’s reality: she is neither idealized nor demonized but exists as a reminder of a world that Ashley cannot return to.

Her presence forces him to reckon with the irreversible consequences of his transformation and the bitter irony that the very rituals he performs to heal others are rooted in a death he could neither prevent nor reconcile.

Keane Withers

Keane Withers is a secondary yet thematically significant figure who mirrors Ashley’s descent into grotesque self-degradation. A meth-addicted, toothless young man drawn into the orbit of a pornographic predator, Keane becomes a victim of manipulation and performance under the guise of empowerment.

Tasked with seducing and blackmailing a performer named Mace, Keane’s plan spirals into murder and cannibalistic madness. His toothlessness—a detail both pathetic and symbolically emasculating—marks him as a figure already broken, easily manipulated by those in power.

Initially driven by desperation and shame, Keane gradually loses his grasp on reality, interacting with inanimate objects as if they possess consciousness and descending into a literal consumption of the dead. His psychological collapse is exacerbated by betrayal, captivity, and voyeurism.

Keane becomes the embodiment of what happens when a vulnerable individual, already teetering on the edge, is thrust into a perverse system that exploits suffering for spectacle. His arc, marked by degradation and isolation, parallels Ashley’s in disturbing ways, offering a nightmarish counterpoint to the narrator’s ritualized delusions of mercy.

Jinx (masterjinx76)

Jinx is perhaps the most enigmatic and destabilizing character in the novel. A client who seeks Ashley’s services, Jinx is young, beautiful, and disturbingly perceptive.

He subverts the power dynamics Ashley is used to, challenging him intellectually, emotionally, and sexually. From their first encounter, Jinx destabilizes Ashley’s routines—forcing him to swallow a marble as a test of trust, questioning his intentions, and unearthing buried truths.

Jinx seems to understand Ashley more deeply than Ashley understands himself. He pokes at the wounds of Ashley’s guilt and repression, particularly around Bailey’s queerness, exposing the contradictions between Ashley’s rituals and his real motivations.

Jinx’s alleged confession to Bailey’s abduction and murder introduces a terrifying ambiguity. Is he telling the truth, manipulating Ashley for sadistic pleasure, or acting as a symbolic vessel for Ashley’s repressed guilt?

His behavior—alternately submissive, mocking, and tender—keeps the reader and Ashley in a constant state of dread. Jinx personifies the novel’s central tension: the thin, porous boundary between suffering and desire, healing and violation.

Whether monster or martyr, Jinx forces Ashley into confrontation with his darkest impulses, and by doing so, becomes both the agent of his possible redemption and the spark of his ultimate moral collapse.

Dubois

Dubois is a grotesque caricature of exploitative power, a man who profits off others’ degradation under the pretense of artistry and commerce. Operating an adult entertainment empire in Henley’s Edge, Dubois embodies the intersection of capitalistic greed and sexual perversion.

He lures Keane into his web with promises of money and purpose, only to manipulate and trap him in a live-streamed snuff performance. Dubois is not merely a facilitator of horror; he is its architect, orchestrating circumstances that ensure both violence and helplessness.

His aesthetic—overwhelming cologne, cheap jewelry, BDSM décor—parodies glamor while revealing a core of predatory rot. As a figure of control, Dubois symbolizes the systemic forces that exploit trauma, pain, and desperation for entertainment.

His influence on Keane’s fate underscores one of the novel’s key themes: the way trauma can be commodified, fetishized, and sold under the guise of transformation or art. Dubois is not just a villain but a reflection of a broader, cultural depravity that revels in others’ ruin.

Tandy

Tandy is a peripheral but ideologically significant character who influences Ashley through his unsettling online confessions. His blog, which details the eroticization of his husband Victor’s cancer, horrifies Ashley yet also appeals to his increasingly warped belief that suffering is sacred.

Tandy’s loss of love once Victor is cured reveals a chilling worldview in which pain becomes the only legitimate foundation for intimacy. His story acts as a mirror for Ashley’s evolving sense of purpose.

If Tandy sees suffering as an aphrodisiac, Ashley begins to see it as spiritual salvation. The alignment between these two men is more ideological than narrative, yet it deepens Ashley’s descent.

Tandy functions as a prophet of a dark gospel, in which mercy is indistinguishable from mutilation, and love cannot survive the absence of grief. He is the echo chamber that reinforces Ashley’s most dangerous delusions, granting them a disturbing kind of philosophical coherence.

In this way, Tandy represents how easily private perversions can be legitimized when couched in poetic language and shared sorrow.

Mace Cavalier

Mace Cavalier is a tragic yet morally complex figure—a pornographic performer caught in the crosshairs of manipulation and blackmail. Known for his flashy signature piercing, the Emerald Centipede, Mace exudes performative confidence but is, ultimately, just as vulnerable as Keane.

When tricked into a sexual encounter under false pretenses, his panic and fear highlight the way shame and legality can weaponize desire. Mace’s fate—strangled and mutilated with a corkscrew—represents the horrifying climax of voyeurism, deception, and survival.

Though he is initially portrayed as an object of lust and reputation, his final moments elicit a tragic recognition of how everyone in this world, no matter how seemingly powerful, is disposable. Mace’s death becomes a grotesque performance in itself, staged for voyeurs and embedded forever in the traumatic legacy of both Keane and Ashley.

His brief presence in the novel lingers, not just in horror, but in the devastating reminder that even perpetrators of spectacle are often its victims too.

Themes

Ritual as Control and Catharsis

In At Dark I Become Loathsome, ritual operates not only as a symbolic act of transformation but as a means for the narrator, Ashley, to impose structure upon chaos and assert a sense of dominion over his disintegrating life. The burial ceremonies Ashley performs, framed as therapeutic tools for those grappling with grief or suicidal ideation, allow him to engineer moments of controlled trauma.

These simulations of death momentarily suspend reality and enable both the client and Ashley to inhabit a liminal state, where suffering might be transmuted into relief. For Ashley, however, the ritual is not merely a service—it becomes a form of emotional currency.

With every burial, he relinquishes a piece of himself, while also extracting power from the vulnerability of others. In this structured theater of mortality, Ashley becomes both priest and executioner, orchestrating intimacy without enduring the messiness of sustained connection.

His growing inability to distinguish between symbolic death and actual harm—evidenced by the live burial of an elderly woman and his final encounter with Jinx—suggests that ritual has transformed into pathology. What began as catharsis for others has become Ashley’s coping mechanism, his compulsive response to grief, guilt, and his obsession with control in a world where he has lost everything that once anchored him.

Grief, Guilt, and the Haunting of Unresolved Loss

Ashley’s existence is dominated by two gaping absences: the death of his wife, Pema, and the disappearance—and presumed death—of his son, Bailey. These losses form the emotional scaffolding of the novel, reverberating through Ashley’s hallucinations, rituals, and moral choices.

His hallucinations are not merely manifestations of trauma but confrontations with truths he refuses to accept: his queerness, his failures as a parent, and the subconscious ways he pushed Bailey away. The grief he experiences is not linear or redemptive—it is circular and consuming.

Even acts that might resemble healing, such as interacting with clients or forming a tenuous connection with Jinx, are ultimately driven by unresolved guilt. The moment Ashley is forced to acknowledge the possibility that Jinx harmed Bailey, grief gives way to vengeance, but that transition is neither clean nor morally righteous.

Instead, Ashley is haunted not only by what he has lost but by what he might have become in the process: someone who confuses redemption with punishment, mercy with death. When he cradles the old woman’s corpse and murmurs “Happy birthday,” he unconsciously collapses the boundary between his dead son and his victims, suggesting that his grief has metastasized into something that can no longer differentiate between mourning and mutilation.

Power, Vulnerability, and the Desire for Dominance

The story presents a deeply disturbing meditation on how power is sought and expressed through vulnerability, especially when emotional wounds remain open. Ashley’s need to dominate his ritual participants under the pretext of healing is directly linked to his feelings of helplessness over Pema’s illness and Bailey’s disappearance.

Each ritual becomes a stage where Ashley can reclaim control, even if momentarily, by scripting life-and-death scenarios that others must perform. The figure of Jinx complicates this pattern.

Unlike Ashley’s earlier clients, Jinx resists being fully objectified or pitied. He challenges Ashley’s assumptions, demands reciprocation, and weaponizes his own beauty and trauma to assert autonomy.

Their interactions oscillate between emotional intimacy and psychological warfare, exposing Ashley’s desperate need to feel both in command and desired. In contrast, Keane’s narrative portrays another form of exploitation, one where vulnerability is not just manipulated but commodified for spectacle.

His descent into cannibalistic madness represents the extreme edge of what happens when agency is stripped and pain is consumed as entertainment. Both arcs suggest that when individuals are pushed to their psychological brink, the distinction between dominance and submission becomes not just blurry but irrelevant—each becomes a means of surviving unbearable emotional reality.

Queerness, Shame, and the Search for Redemption

Sexuality in At Dark I Become Loathsome is fraught with secrecy, shame, and longing, particularly as it intersects with Ashley’s experience of fatherhood and personal identity. His queerness, while not explicitly hidden, is treated as a source of deep inner conflict—one that shaped his relationship with Bailey and continues to influence how he sees himself.

The suggestion that Ashley disapproved of Bailey’s gender expression, particularly the haunting image of the boy in a wedding dress, reveals a past riddled with emotional withholding. Now, in his interactions with Jinx—who embodies and embraces a defiant kind of queerness—Ashley is confronted by everything he tried to suppress.

Jinx’s presence is seductive and terrifying precisely because he forces Ashley to confront the part of himself that he abandoned long ago. The sexual tension between them is inseparable from the dynamics of guilt, envy, and moral confusion.

Ashley does not know whether to kiss Jinx, kill him, or be saved by him. This confusion culminates in the schoolhouse scenes, where Ashley’s violent desire to extract truth from Jinx is interwoven with erotic vulnerability.

Redemption, if it exists, is momentary and spectral—captured only in Ashley’s decision not to kill Jinx after Bailey’s apparition intervenes. But the clarity is fleeting, and Ashley’s return to the grave of the old woman signifies that the wounds of shame, queerness, and loss remain unresolved, only transmuted into new rituals of self-punishment.

The Spectacle of Suffering and the Collapse of Empathy

Throughout the novel, pain becomes performance—whether in the form of live-streamed murders, carefully orchestrated burials, or emotional manipulation disguised as intimacy. Dubois’s business in Keane’s arc represents the most literal version of this dynamic, with suffering turned into commodity and consumed by unseen audiences.

But Ashley’s story is no less performative. His careful staging of rituals, attention to dramatic details, and refusal to acknowledge boundaries between therapeutic catharsis and entertainment suggest that empathy has been replaced by spectacle.

What begins as a genuine attempt to understand suffering mutates into an obsession with the aesthetics of pain. Even when Ashley tells himself he is offering relief, he is often feeding his own need to witness transformation—to feel something vicariously through the suffering of others.

This is particularly evident in his fascination with Tandy’s blog, where illness becomes eroticized, and death is perceived as an aphrodisiac. The blurring of empathy and voyeurism reflects a broader moral collapse, where Ashley can no longer recognize the line between helping and harming.

By the end of the novel, he is not a passive observer but an active orchestrator of death, cloaked in language of peace and mercy. The reader is left to confront the unsettling truth that Ashley, once a man broken by grief, has become someone who finds meaning not in healing others but in watching them crumble—and perhaps, in becoming the one to orchestrate their final collapse.