At the Bottom of the Garden Summary, Characters and Themes

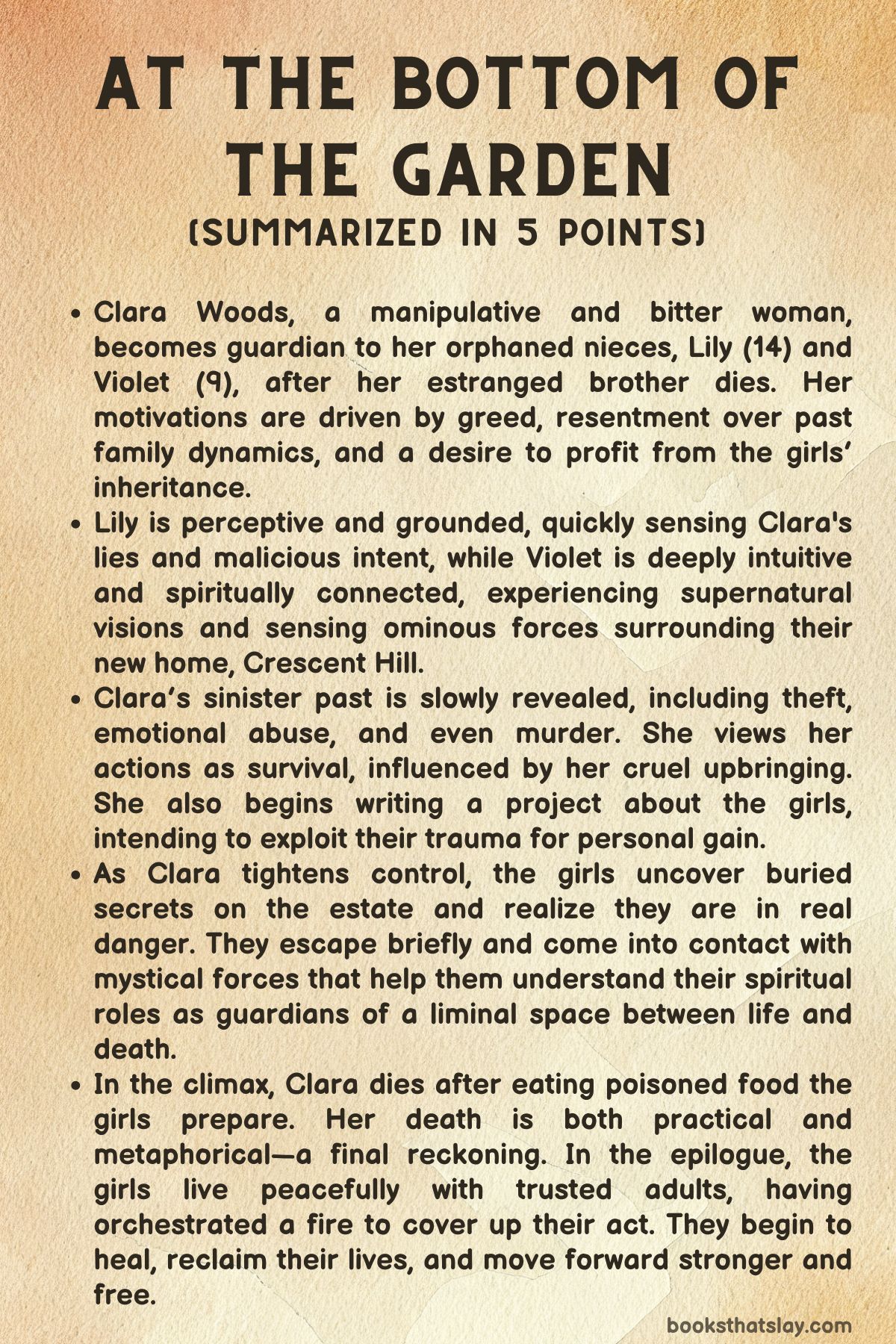

At the Bottom of the Garden by Camilla Bruce is a chilling and atmospheric tale that blends psychological manipulation, supernatural horror, and familial trauma. The novel follows the lives of two orphaned sisters, Lily and Violet Webb, who are forced to live under the care of their estranged Aunt Clara Woods after their parents die on a climbing expedition.

What begins as a story of grief and reluctant guardianship quickly spirals into a gothic narrative brimming with ghostly hauntings, magical abilities, and the sinister greed of a woman determined to exploit her nieces for financial gain. Through a shifting narrative of multiple perspectives, Bruce crafts a darkly intimate exploration of power, legacy, and resilience.

Summary

After the tragic deaths of Benjamin and Marianne Webb on K2, their young daughters Lily and Violet are left orphaned. Their reluctant guardian becomes Clara Woods, Benjamin’s half-sister, who seizes the opportunity not out of familial loyalty but for financial advantage.

Clara resents her brother’s wealth and charm and agrees to take the girls in primarily to gain access to their trust fund and receive a monthly stipend. Clara’s inner monologue reveals her disdain for her family, her obsession with diamonds, and her carefully curated performance of grief when meeting with Miss Feely, the social worker overseeing the girls’ welfare.

Lily, the older sister, quickly sees through Clara’s façade. Practical and emotionally intelligent, she maintains her focus on protecting her younger sister.

Violet, while more naive, has a unique gift: she perceives emotions as colors and can sense the presence of spirits. As the girls move into Clara’s eerie estate in Ivory Springs, they are surrounded by taxidermy animals and ghostly entities, including the spirit of the home’s previous owner, Cecilia Lawrence, whom only Violet can see.

Clara claims to have inherited the home from Cecilia, whom she once cared for as a nurse, but her account is full of inconsistencies.

As the girls adjust to their unsettling new environment, Violet’s spiritual sensitivities intensify. She communicates with the ghostly remnants of both animals and people and forms a bond with a raven-like spirit called Irpa.

Violet begins to conduct small rituals to release trapped souls, sensing that some ghosts are angry or sick. Lily, grounded in reason and protective instinct, struggles to accept Violet’s abilities but recognizes their increasing importance.

Clara, meanwhile, is preoccupied with looting the estate for valuables and plotting how to gain full control of the inheritance.

Clara’s grip on reality begins to fray as her home becomes increasingly haunted by the ghosts of her own victims—her late husband Timothy Woods and his lover Ellie Anderson among them. The girls, particularly Violet, are aware of these presences, and Violet’s encounters with the dead become more intense.

Clara tries to manipulate Violet into using her powers to expel the spirits, staging a séance in the hope of ridding the house of its ghostly infestations. During the event, Violet becomes possessed by the dead, each spirit denouncing Clara’s crimes.

The séance ends in chaos, with a blackout and spoiled offerings, and Violet falls ill from the supernatural strain.

Despite Violet’s worsening health, Clara remains undeterred. She begins to exploit Violet’s powers by staging paid séances, convincing a wealthy widow, Mrs.

Arthur, to pay for a session. Clara’s old friend Gail, a spiritual enthusiast, helps facilitate the meeting, but the consequences grow darker as Violet’s connection to the spirit world deepens.

Clara’s obsession with launching a diamond brand, Clarabelle Diamonds, consumes her focus, even as her relationships with everyone around her deteriorate.

Lily becomes increasingly desperate to save Violet. When she tries to dig up the bodies Clara buried in the garden to provide evidence of her crimes, the ghosts intervene, particularly Mr.

Woods, whose ghost violently warns them not to disturb his grave. The girls realize they are trapped not only by Clara’s manipulation but also by the unresolved needs of the dead.

Clara’s greed and paranoia lead her to become more dangerous, planning to take Violet on the road for séance performances. This final scheme galvanizes the girls’ resolve.

In a brief escape to a secluded lake house, the sisters experience a rare moment of peace. They discover a mystical statue hidden in the woods—half skeletal, half fertile mother—guarding a sacred stream.

Drinking from the stream bestows strange powers upon them, including levitation. They feel briefly free, connected to something ancient and powerful.

However, the moment is short-lived. Police arrive with Clara, who forcibly retrieves the girls.

Her rage and resentment explode, and she berates them for fleeing. This confirms to the sisters that their survival depends on drastic action.

Back at Crescent Hill, Lily and Violet come to a grim consensus: Aunt Clara must die. With the help of Dina, a kind-hearted housekeeper, they concoct a plan to poison her with wild mushrooms.

Lily prepares the meal, and Violet serves it without hesitation. As Clara begins to suffer, she realizes she’s been betrayed but is too weakened to retaliate.

The sisters, hand in hand, watch her die, enveloped in a magical glow that symbolizes their dual inheritance: Lily radiant and hard like a diamond, Violet shadowed and smoldering like ash.

In the aftermath, the sisters, along with Dina and her husband, set fire to Crescent Hill to cover Clara’s death. They use the insurance money to settle debts and distribute Clara’s valuables.

They move to a farm where Lily learns animal care and healing, and Violet continues her work guiding spirits. Though free, their experience has changed them.

Lily is haunted by the morality of their decision, while Violet is more accepting of the necessity of killing for survival.

The final scenes return to the lake house, where the girls offer gifts to the supernatural statue and recommit to their roles as border-keepers between the living and the dead. Their powers have grown, as has their understanding of their place in the world.

Though Clara is gone, the legacy of trauma, magic, and sisterhood continues to shape their lives. They are no longer just survivors—they are keepers of ancient rites, balancing justice and mercy in a world that demanded they grow up far too soon.

Characters

Clara Woods

Clara Woods emerges as the primary antagonist of At the Bottom of the Garden, a woman consumed by bitterness, greed, and a relentless pursuit of power cloaked in jewels. Her decision to take custody of her nieces, Lily and Violet, is rooted not in familial duty or compassion but in an opportunistic desire to access their inheritance and secure financial backing for her diamond business, Clarabelle Diamonds.

Clara’s worldview is transactional; she measures affection by its utility and sees relationships as stepping stones toward wealth and control. Her interactions are carefully curated performances—designed to charm social workers, manipulate old friends, or deceive her young wards.

Yet beneath this polished façade lies a cauldron of resentment, particularly toward her late half-brother, Benjamin, whose privileged life she envied.

Clara is not merely greedy—she is pathologically controlling. Her insistence on Violet’s supernatural gifts being monetized reveals a chilling disregard for the girl’s health and agency.

Even as Violet collapses from exhaustion and illness, Clara pushes forward with séances, seeing only dollar signs in the ghostly realm. Her cruelty is not impulsive but premeditated, exemplified in her history of murder, manipulation, and her cold calculations about how to silence dissent.

Clara’s home, filled with taxidermy and haunted relics, is a mirror of her own psyche—ornate but hollow, beautiful but dead. Her ultimate demise, poisoned by the very children she sought to control, is both a moral and supernatural reckoning.

Clara becomes a cautionary embodiment of unchecked avarice, a woman who saw the world only in carats and contracts, and who paid dearly for ignoring the living and the dead alike.

Lily Webb

Lily Webb serves as the emotional compass of At the Bottom of the Garden, a girl whose poise, maturity, and quiet resilience form the backbone of the narrative. As the older of the two orphaned sisters, Lily assumes a maternal role toward Violet, becoming both protector and anchor in their chaotic descent into Clara’s haunted world.

Her character is marked by an extraordinary capacity for observation and an underlying strategic intelligence. She recognizes early on that survival may depend on compliance, yet she never surrenders her skepticism.

Lily’s keen perception is heightened by a synesthetic ability to see emotions as colored flames—a symbolic representation of her emotional intelligence and intuitive defenses.

Lily’s grief for her parents is profound but deeply internalized. She attempts to preserve their values—especially her mother’s quiet humility and strength—even as she navigates the manipulative environment of Crescent Hill.

Her discomfort with the supernatural, particularly Violet’s ghostly encounters, signals an inner struggle between rationality and belief. While Violet embraces the spectral, Lily remains grounded, a contrast that defines their sibling dynamic.

Her moral arc reaches a painful climax when she accepts the necessity of Clara’s death, a choice made not from vengeance but as a grim calculation to ensure their survival. Lily’s transformation—from grieving child to reluctant conspirator—reflects a loss of innocence, yet she retains a fierce sense of justice and responsibility.

By the end, her evolution into a caretaker and healer signals a desire to mend the damage inflicted upon her, Violet, and the world around them.

Violet Webb

Violet Webb stands at the heart of the novel’s magical and moral complexity, a child endowed with an innate ability to see and interact with the dead. While her older sister Lily embodies rationality and control, Violet represents intuition and spiritual permeability.

Her emotional depth is expressed not only through grief but through a kind of mystical empathy—she perceives the world through colors, energies, and voices others cannot hear. From the moment she enters Clara’s eerie home, Violet begins to engage with the spectral presences that haunt it, including the ghost of Cecilia Lawrence and the taxidermied remnants of animals whose souls remain tethered to the physical world.

These interactions are not whimsical hallucinations but sacred communications; Violet becomes a vessel for the unresolved anguish of the dead.

Despite her youth, Violet shoulders a spiritual burden far beyond her years. Her communion with Irpa, a raven spirit, and her ritualistic offerings to ghosts speak to a role that borders on priestess or shaman.

These moments are not without consequence: the toll on her body and mind is significant, and her growing alienation from Lily creates emotional tension. She is both a visionary and a child deeply in need of protection.

Yet Violet is not a passive victim. Her complicity in Clara’s murder, while disturbing, underscores her growing awareness of the darkness in the world and her willingness to confront it head-on.

Ultimately, Violet is a liminal figure, straddling the boundary between life and death, innocence and moral agency. Her role as a guide for lost souls and her continued connection to the sacred lake position her as a powerful, if unsettling, inheritor of ancient magic.

Sebastian Swift

Sebastian Swift occupies a peripheral yet meaningful role in Clara’s narrative arc in At the Bottom of the Garden. As her lover and a fellow enthusiast of rare jewels, he represents both a confidante and an accomplice in her aesthetic aspirations.

Their relationship is characterized less by intimacy and more by mutual indulgence in luxury and status. Clara shares parts of her ambition with Sebastian but keeps her darker deeds hidden, revealing the limitations of trust even in her closest relationships.

His presence serves to underscore Clara’s performative charm and ability to seduce people into believing in her curated identity.

Sebastian’s eventual distance from Clara mirrors her unraveling control. As she becomes more unhinged, obsessive, and desperate, her ability to manipulate him weakens.

His absence in Clara’s final acts suggests that even those once seduced by her glittering façade eventually recognize the void beneath. Sebastian may not be central to the plot’s supernatural or moral conflict, but he plays a thematic role in highlighting how Clara’s relationships are transactional, fragile, and ultimately doomed by her insatiable hunger for wealth and power.

Dina

Dina, the housekeeper at Crescent Hill and eventual guardian to Lily and Violet, stands as one of the few morally grounded adults in At the Bottom of the Garden. Her kindness, discretion, and quiet loyalty offer a crucial counterbalance to Clara’s cruelty.

Though initially a passive observer in the household’s dysfunction, Dina’s loyalty subtly shifts as she becomes aware of the girls’ suffering. Her evolution from caretaker to co-conspirator is a testament to her growing sense of justice and maternal instinct.

Dina’s decision to help the girls orchestrate Clara’s downfall and later cover up her death through fire and insurance fraud illustrates a moral pragmatism that blurs the line between right and wrong. She is not driven by vengeance or gain but by a fierce protective love.

Her home becomes the girls’ sanctuary, a place of healing, growth, and reconciliation. Dina represents the possibility of redemption in a story suffused with betrayal and loss.

Through her, the girls find the adult ally they so desperately needed—someone who listens, believes, and ultimately chooses them over propriety or self-preservation.

Mr. Woods

The spectral presences of Timothy Woods and Ellie Anderson, Clara’s deceased husband and his lover, serve as more than ghostly hauntings—they are embodiments of Clara’s past sins and the moral reckoning that shadows her present. Their appearances are filled with rage and demand for acknowledgment, particularly during the séance scenes when they possess Violet and condemn Clara before witnesses.

These ghosts are not gentle apparitions; they are violent, vengeful, and unwilling to let Clara rewrite history.

Their resistance to the girls digging up the buried bodies in the garden reveals their own tangled desires—not for peace, but for preservation of a haunting power that keeps them tethered to the world. They complicate the narrative by refusing easy absolution.

Mr. Woods, especially, remains a menacing figure even in death, suggesting that trauma and abuse can echo far beyond the grave.

Their presence underscores one of the novel’s key tensions: that truth, once buried, rarely stays hidden, and the dead have their own agendas.

Irpa and the Statue Lady

Irpa, the raven spirit who serves as Violet’s guide, and the mysterious statue lady in the woods function as the metaphysical pillars of At the Bottom of the Garden. Irpa is Violet’s most constant and enigmatic companion, appearing when guidance is most needed and reinforcing Violet’s role as an intermediary between realms.

He represents instinct, ancient knowledge, and the spectral intelligence of the natural world. His presence comforts Violet and empowers her to make sense of the spirits around her.

The statue lady, discovered near the sacred stream, embodies the novel’s core dualities—life and death, beauty and decay, nurturing and destruction. She becomes a totem of the sisters’ transformation, particularly in the floating scene where magic and grief intermingle.

The statue doesn’t speak, but her presence demands reverence and commitment, asking the girls to embrace their inherited responsibility as boundary-keepers between the living and the dead. She symbolizes the ancestral, matriarchal power that has always lurked beneath their suffering, now awakening through their choices.

Through her, the girls are not merely survivors—they are reborn into something ancient, terrifying, and transcendent.

Themes

Greed and Exploitation

Clara Woods is a character defined by her relentless pursuit of wealth and status, and her willingness to exploit vulnerable children for personal gain. Her choice to take in her orphaned nieces is not motivated by familial obligation or love but by a calculated interest in their inheritance and the monthly stipend she will receive.

She manipulates the legal and emotional frameworks of guardianship to her advantage, presenting a façade of compassion to social workers while secretly harboring deep resentment for her deceased half-brother and his “easy” life. Clara’s entire persona is constructed around accumulation—of wealth, of possessions, of social capital—and her home reflects this with its hoard of taxidermy, antiques, and jewelry.

Her obsession with diamonds, which she sees as enduring symbols of power and beauty, mirrors her transactional view of human relationships. Even her romantic relationship with Sebastian Swift is laced with deceit and secrecy, as she hides her more sinister inclinations to maintain the illusion of control.

Clara’s descent into more dangerous exploitation—using Violet’s supernatural gifts to stage paid séances—demonstrates how greed metastasizes into cruelty. She treats Violet as a marketable asset, completely ignoring the toll it takes on the child physically and emotionally.

This theme is not merely about Clara’s individual flaws; it critiques systems that allow such exploitation to flourish unchecked under the guise of guardianship or entrepreneurship. Her manipulations underscore a broader indictment of opportunism, revealing how easily affection and responsibility can be commodified when unchecked ambition is allowed to govern human relationships.

Childhood Resilience and Sisterhood

Lily and Violet’s story is rooted in the fierce emotional bond between sisters navigating trauma, isolation, and spiritual mystery. Their parents’ death uproots them into a household of psychological abuse and supernatural peril, yet their connection remains the central source of strength and sanity.

Lily, the older sister, assumes a maternal role, balancing survival strategies with a quiet but fierce resistance to Clara’s lies. Her pragmatism and emotional intelligence become key defenses against manipulation.

Meanwhile, Violet, the younger of the two, approaches their new reality with a sense of wonder and intuitive power, relying on her extrasensory gifts to interpret and navigate threats both physical and metaphysical. Their differences—rationality versus intuition, control versus surrender—do not divide them but complement one another in their shared goal of survival and, eventually, justice.

Their resilience is evident not just in their endurance but in their capacity to plan, act, and even kill when necessary. This culminates in the decision to poison Clara—an act that is morally complex but framed as the only way to ensure their safety.

Even as they inherit magical abilities and supernatural responsibilities, their bond remains grounded in mutual care. The theme of sisterhood is never saccharine or idealized; instead, it portrays an evolving alliance forged in crisis.

Their shared experience binds them not just emotionally but mystically, allowing them to become guardians of life and death in their own right. The theme reinforces the idea that familial love, when rooted in mutual respect and protection, can outlast and overpower even the most corrosive forms of betrayal and abuse.

Supernatural Power and Moral Responsibility

Violet’s ability to see and interact with the dead, and Lily’s eventual development of mystical powers, create a narrative landscape where spiritual gifts are both burdens and tools. These supernatural powers are not treated as fantastical boons but as inheritances that demand accountability.

Violet, from the beginning, is depicted as someone deeply attuned to the emotional and spectral residue around her. She performs rituals to release trapped spirits, negotiates with angry ghosts, and navigates the intense psychological toll of being a medium.

Her powers make her vulnerable—not only to ghosts but to exploitation by Clara, who sees dollar signs where Violet sees suffering. The turning point of Violet’s powers—being possessed by multiple ghosts during a séance—underscores the theme’s gravity: the spiritual world is neither benign nor forgiving, and those who mediate it must tread carefully.

Lily, initially skeptical of the supernatural, grows into her own abilities, learning to use music and healing as bridges between realms. This divergence—Violet leaning into the spectral, Lily into the earthly—emphasizes that power must be matched with intent and ethical clarity.

Their final act of killing Clara, though facilitated by mundane means, is steeped in magical symbolism and ritual, positioning them as judges and executors of justice. The supernatural in the story functions not just as atmosphere or metaphor but as a moral force—one that holds the living accountable for the suffering they cause.

Through this lens, the girls’ powers are not privileges but responsibilities, forcing them to confront what it means to intervene, to punish, and to protect in a world where death lingers close.

Justice, Vengeance, and Moral Ambiguity

The novel interrogates the fine line between justice and vengeance through Clara’s eventual downfall at the hands of the very children she sought to exploit. While Clara’s crimes are clear—manipulation, abuse, murder, and supernatural coercion—the response to her actions is far from straightforward.

Lily and Violet, despite being children, bear the responsibility of enacting what no adult seems willing or able to do: stopping Clara permanently. Their decision to kill her is not taken lightly, and the narrative treats it with psychological and moral complexity.

Lily struggles with the implications, even as she recognizes it as a necessary evil. Violet, more comfortable with spiritual death and resurrection, sees the act as part of a larger cosmic balance.

Clara’s death is framed as a reckoning—not only of her earthly crimes but of her spiritual trespasses. The ghosts curse her, her house burns down, and she is consumed by the very forces she sought to control.

Yet the girls’ role in this act blurs the boundaries of innocence and guilt. They become agents of a new form of justice, one that is both intuitive and retributive, and deeply tied to their supernatural identity.

This moral ambiguity is never fully resolved; instead, it lingers in the firelit aftermath, in Lily’s guilt and Violet’s certainty. The story invites readers to question what justice looks like when conventional systems fail, and whether vengeance can ever be clean when executed in defense of the powerless.

The result is a haunting meditation on the costs of justice in a world where the dead demand to be heard and the living must carry the burden of that hearing.

Inheritance and the Legacy of Trauma

The question of what is passed down—genetically, emotionally, and spiritually—is central to the novel. Clara’s greed is fueled by her own history of neglect and emotional abuse, particularly from her mother, Iris.

Her desire to accumulate wealth and power stems from a need to transcend the indignities of her past. Yet rather than transforming pain into compassion, Clara perpetuates the very cycles that harmed her.

This legacy of trauma becomes a curse that spreads from one generation to the next. Lily and Violet, as the next in line, are forced to confront and break this inheritance—not through passive endurance but through active rejection.

Their final act of burning down the house and redistributing Clara’s wealth symbolizes a cleansing of the familial wound. At the same time, they inherit something intangible yet potent: a connection to the statue-lady, to the stream, to the liminal space between life and death.

This inheritance is as much a burden as a gift. It places them in a lineage of spiritual caretakers, charged with guarding the balance between worlds.

The statue-lady’s dual nature—life and death, beauty and decay—mirrors the girls’ internal transformation. In the end, they choose what parts of their legacy to carry forward and what to leave behind.

This selective inheritance marks a departure from the fatalism that shaped Clara’s life. It offers a model of intergenerational healing that acknowledges pain without allowing it to dominate.

Through the girls, the narrative offers a hopeful yet sobering vision of what it means to inherit both trauma and magic, and to make something just out of that inheritance.