Bad Friend by Tiffany Watt Smith Summary and Analysis

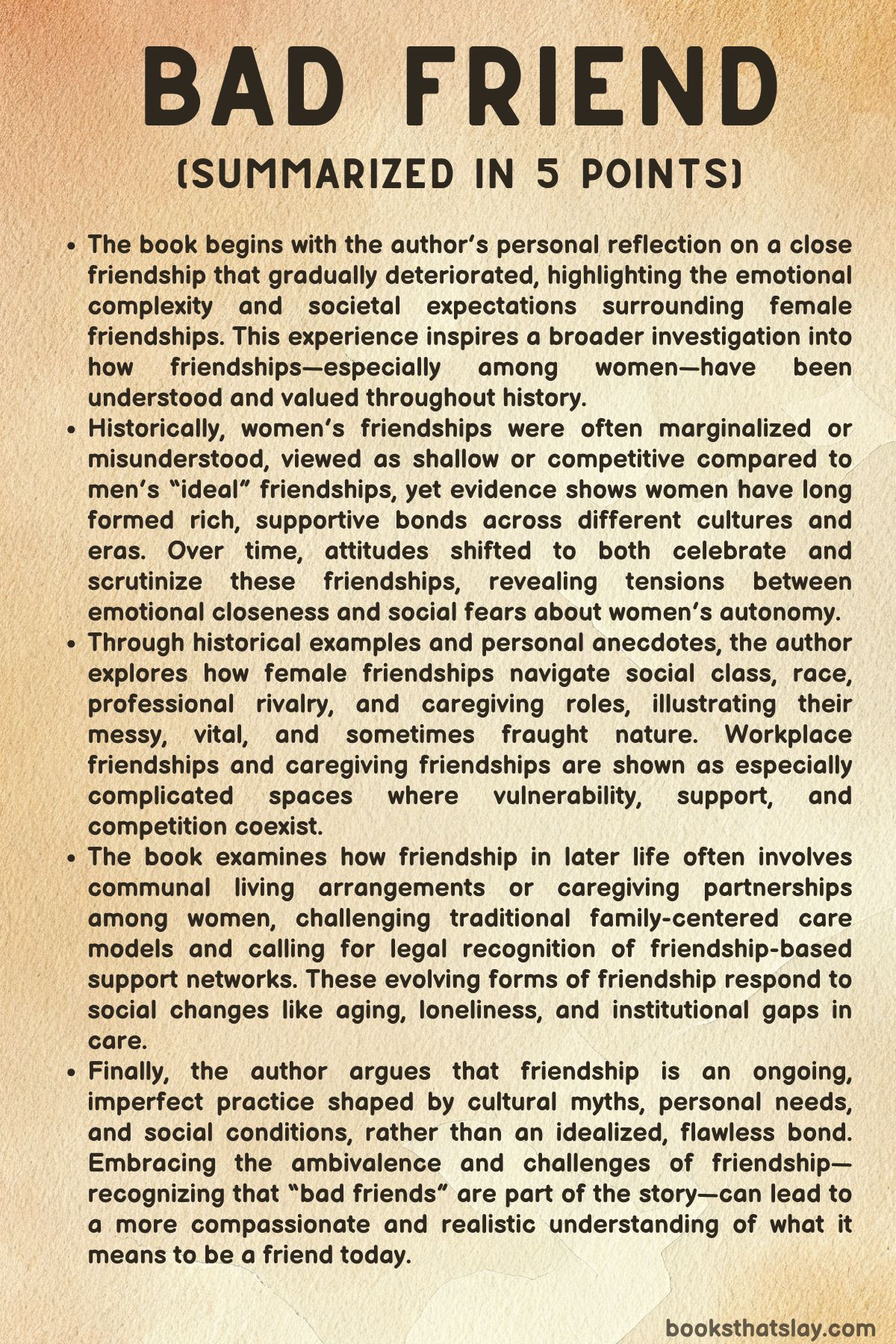

Bad Friend by Tiffany Watt Smith is a thoughtful exploration of the complex and often contradictory nature of female friendships through history, culture, and personal experience. Combining memoir, historical research, and cultural critique, the book challenges the idealized and sometimes unrealistic expectations placed on women’s friendships.

It reveals how friendships are shaped by societal norms, emotional challenges, and changing social contexts—from youthful bonds to caregiving in later life. By examining friendships’ fluidity, messiness, and imperfections, the author argues for a more compassionate and realistic understanding of what it means to be a friend today.

Summary

The book opens with a personal reflection on the narrator’s fading friendship with Sofia, capturing the pain of drifting apart despite a once-close bond rooted in youth and shared dreams. Sofia was ambitious and magnetic, while the narrator admired her deeply but eventually felt left behind and excluded as Sofia’s life moved forward with new successes and relationships.

This painful experience highlights the tension between idealized notions of female friendship and the often complicated, imperfect reality. Motivated by this, the narrator—herself a historian of emotions—embarks on an exploration of the history, cultural politics, and emotional landscape of friendship, particularly among women.

Historically, Western philosophy elevated male friendship as the ideal human connection, characterized by virtue and mutual respect, while women’s friendships were often dismissed as superficial or driven by utility and rivalry. Women’s friendships were rarely acknowledged in grand narratives due to social biases portraying them as emotionally volatile or competitive.

However, fragments of history reveal that women have always formed meaningful, sometimes intense friendships that encompassed emotional, economic, and spiritual dimensions. Examples span from medieval women caring for each other, to early modern women’s legal and financial partnerships, to passionate bonds documented through letters and poetry.

The cultural view of female friendship began to shift during the eighteenth century, as women’s friendships came to be seen as emotionally rich and deeply devoted, contrasting with men’s more reserved connections. The nineteenth century further idealized female friendship as “romantic” and intensely loyal, often linked to ideas of motherhood and female empowerment.

Yet this idealization coexisted with suspicion and pathologization, particularly in the early twentieth century. Intense girlhood friendships or “romantic friendships” were sometimes viewed as dangerous or deviant, reflecting broader anxieties about female sexuality, autonomy, and changing social roles.

The author illustrates these themes with personal stories, such as a turbulent friendship with a woman named Liza, which was marked by longing, identity struggles, and heartbreak. This narrative acts as a microcosm of the emotional complexity and challenges inherent in female friendships.

The history of friendship is also intertwined with social class, race, and urbanization; for instance, immigrant women in early 20th-century America formed vital friendships for survival and solidarity but faced condemnation as “bad company” from reformers.

Central to the book is the notion of the “bad friend” trope—how cultural expectations around female friendship create impossible standards that lead to guilt, shame, and anxiety when relationships falter. These pressures persist today, as popular culture warns against toxic friends and betrayal, underscoring enduring fears about loyalty, trust, and emotional vulnerability.

The narrative also explores the ambiguity and fluidity of friendship. Unlike family or romantic relationships, friendship lacks clear social rules or institutions, requiring each relationship to be continually invented and nurtured.

The author advocates for a flexible, compassionate approach to friendship that accepts imperfection and complexity, recognizing that “bad friends” and difficult moments are part of the normal experience.

Further personal reflections include childhood friendships with fearless and rebellious girls like Sofia, which helped the author discover identity and power beyond restrictive domestic roles. The challenges of forming friendships in adult, often male-dominated professional environments are also examined, where women navigate vulnerability, rivalry, and strategic networking.

This contrasts with earlier historical rules for women’s conduct in friendships, such as seventeenth-century household guidelines that warned against gossip and over-intimacy but were often defied by real women’s experiences.

The early twentieth century saw working women face warnings about jealousy and betrayal in friendships, yet popular culture at the time, notably films by Dorothy Arzner, depicted female friendships as crucial alliances for survival and ambition. These portrayals reflect the tension between individual competition and solidarity that defines many female friendships.

In contemporary life, workplace friendships have gained recognition for their importance, especially for marginalized groups. They provide support and resilience but also come with challenges like emotional labor and social exclusion.

The author expresses a desire for more authentic, spontaneous connections rather than friendships instrumentalized for career gain.

Friendship’s role in community and neighborhood life is explored, showing how casual, transient interactions can offer solace and meaning beyond traditional friendship models. The difficulty of defining “friend” across cultures further reveals the complexity of human connection.

Historically, female sociability has been feared and suppressed, as in witch trials targeting well-connected women, highlighting how female friendships could be both empowering and threatening. Mid-twentieth-century sociological research lamented the decline of close-knit working-class female networks, but further study reveals these communities were often marked by ambivalence and conflict, challenging nostalgic narratives.

The book also examines friendship in times of crisis and caregiving, especially the emotional labor friends provide during illness and death—roles often overlooked or institutionalized by society. Personal stories of caregiving friendships during the AIDS crisis and contemporary illness demonstrate fierce loyalty and support outside traditional family structures.

The author calls for formal recognition of friendship caregiving through legal frameworks, drawing on historical precedents worldwide, to help protect and support those who care for friends.

As women age, many increasingly choose communal living arrangements with friends, modeled on historical and contemporary examples, to combat loneliness and maintain independence. These communities emphasize mutual support, compromise, and shared responsibility, illustrating a form of friendship that functions as chosen family.

The text concludes by reflecting on the changing nature of friendship in the digital age, noting that while technology can create connections, it can also lead to superficial relationships or deepen loneliness. AI companions offer a new but limited form of friendship, lacking the emotional depth of human bonds.

Ultimately, Bad Friend portrays friendship as an evolving practice requiring effort, compromise, and vulnerability. It argues against idealized or rigid views, urging a recognition that friendship is “good enough” when sustained by small acts of care and the willingness to continue trying despite imperfections.

Through history, personal experience, and cultural analysis, the book reclaims the rich, messy reality of female friendship and offers a fresh framework for understanding friendship today.

Key People

Tiffany Watt Smith, The Narrator

The narrator of Bad Friend serves as both a reflective observer and a deeply personal participant in the exploration of friendship. She embodies the complexities and contradictions of female friendships, experiencing the full spectrum of emotional highs and lows, from deep admiration and longing to jealousy, hurt, and eventual estrangement.

Through her relationship with Sofia, she reveals the painful reality of losing a close friendship to life’s changing circumstances and personal growth. Her role as a historian of emotions adds a unique layer, enabling her to blend personal memoir with cultural critique and historical research.

The narrator is introspective and sensitive, wrestling with societal expectations about what friendship should look like versus its often messy reality. Her vulnerability, self-doubt, and nuanced understanding make her a compelling guide through the text’s thematic journey, as she navigates her own failures and desires to rethink the standards of friendship.

Sofia

Sofia is portrayed as the magnetic and ambitious friend whose life trajectory highlights the tension between friendship ideals and reality. In the narrator’s eyes, Sofia embodies success and forward momentum, advancing into adulthood with new relationships and social circles, which unintentionally sidelines the narrator.

She is both admired and resented—admired for her confidence and vitality, resented for the emotional distance she creates. Sofia represents the kind of friend who becomes elusive as life circumstances diverge, exposing the fragility and unevenness of female friendship.

Her character illustrates how friendship can be affected by social mobility and changing personal priorities, and how the cultural myths about constant female solidarity often obscure the realities of competition, neglect, or drift.

Liza

Liza appears as a figure within the narrator’s personal history who exemplifies the intense and often volatile nature of female friendship. Their relationship is marked by passion, longing, and identity exploration, but ultimately also heartbreak and destruction.

Liza’s presence in the narrative serves to dramatize the emotional intensity and risk that friendships can hold, especially when they intertwine with personal identity and vulnerability. Through Liza, the author conveys the ways in which friendships can be sites of both profound connection and deep pain, embodying the complexities of desire, loyalty, and selfhood in women’s relationships.

Minerva Jones

Minerva Jones is an elusive historical figure introduced to underscore the challenges of tracing working-class Black women’s lives and friendships in early 20th-century Western societies. Her near disappearance from public records symbolizes the broader invisibility of marginalized women’s friendships in dominant historical narratives.

Minerva represents the precariousness and fragility of such friendships amid social and racial hardships, emphasizing the risks of trust and solidarity under difficult conditions. She stands as a testament to the survival and resilience embedded in these often undocumented female bonds, highlighting intersections of race, class, and gender in friendship history.

Ali

Ali is a friend who undergoes a personal crisis when her husband is diagnosed with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing to the fore the challenges of caregiving within friendship. Through Ali’s experience, the narrative explores the awkward, emotionally charged “choreography of helping” that friendships often require in times of illness and trauma.

Ali’s story illuminates the shifting dynamics of friendship in adulthood—how support becomes an active, sometimes difficult labor that involves navigating boundaries, vulnerability, and emotional weight. She exemplifies the real-world demands friendship places on individuals when faced with life’s hardships.

Cas and Rachel

Cas and Rachel’s friendship is a poignant example of caregiving and emotional complexity during serious illness. Cas supports Rachel through her dying process, illustrating the fierce loyalty and intimate care that friendship can provide outside formal family structures.

Their relationship reveals the emotional labor and self-doubt that carers often confront, as well as the social invisibility of friendship caregiving. Together, they embody the deep commitment and imperfections inherent in such bonds, challenging traditional models of care and highlighting friendship as a vital, though often overlooked, form of support.

Rose

Rose represents a friendship shaped and sometimes strained by trauma. Her presence in the narrative draws attention to how difficult experiences can deepen bonds but also create fractures and eventual fading of connections.

Rose’s story exemplifies the bittersweet reality that not all friendships endure unchanged, and that emotional wounds can both connect and divide. She contributes to the text’s exploration of friendship’s fragility, resilience, and the sometimes painful processes of renegotiation and loss.

Elizabeth Carter and Elizabeth Hatchett

These two historical figures illustrate the pragmatic and business-minded aspects of female friendship in the 18th century. Their partnership in pawn-broking reveals that friendships among women have long blended emotional support with practical collaboration and economic survival.

Through their example, the book challenges the simplistic view that women’s friendships are purely emotional or superficial, instead portraying them as multifaceted relationships that often combine care with strategy and mutual benefit.

Hannah Woolley

As a 17th-century servant who prescribed strict rules for female conduct and friendships, Hannah Woolley symbolizes the cultural attempts to regulate and contain women’s sociability. Her warnings against gossip and undue intimacy reflect societal anxieties about the power of female friendships, especially in domestic spaces.

Woolley’s character or persona highlights the tension between imposed social norms and women’s lived realities, where friendships often defied such constraints and flourished despite them.

Dorothy Arzner

Dorothy Arzner is the pioneering Hollywood director whose career and films provide a lens into the portrayal of female friendships in the early 20th century. Arzner’s work depicts women’s friendships as complex, powerful alliances essential for survival and ambition, though marked by rivalry and imperfection.

Her ambivalent relationship with friendship reflects broader cultural tensions between individualism and solidarity among women. Arzner’s figure helps bridge historical, cultural, and media perspectives on female friendship, showing how it has been both idealized and complicated by social realities.

Themes

The Complex Dynamics of Female Friendship

Female friendships, as depicted, challenge simplistic cultural narratives that have historically marginalized or misunderstood women’s emotional bonds. The analysis reveals that women’s friendships often involve intense emotional investment, fraught with jealousy, rivalry, vulnerability, and longing.

These relationships defy the traditional Aristotelian ideal of friendship centered on virtue and mutual admiration, which privileged male friendships and dismissed female bonds as superficial or competitive. Instead, female friendships carry a distinct complexity shaped by social expectations, gendered stereotypes, and cultural anxieties.

The narrative explores how these friendships can be both empowering and painful, serving as vital spaces for identity formation, emotional support, and sometimes personal liberation. The cultural myths and societal pressures surrounding female friendships create impossible standards, casting “bad friends” as failures, yet the reality is that friendships are inherently imperfect, ambiguous, and evolving.

Through historical and contemporary examples, the theme illustrates how women’s friendships have been alternately romanticized and pathologized, reflecting broader tensions about female autonomy and emotional expression. This nuanced view pushes against the idealization of female solidarity by acknowledging rivalry and betrayal as part of the emotional landscape, emphasizing that authentic friendship embraces complexity and imperfection.

Friendship as Emotional Labor and Caregiving

Friendship is shown not only as emotional connection but also as a form of caregiving and labor that is often invisible or unrecognized by formal institutions. The book foregrounds the demanding and intimate roles friends—especially women—play when supporting each other through illness, trauma, aging, and crisis.

This caregiving extends beyond conventional family roles and challenges the dominant social narrative that frames care as primarily a familial or professional responsibility. The historical context provided highlights a rich tradition of women serving as midwives, death doulas, and caregivers to one another, a tradition sidelined by modern institutionalization of care.

Through personal stories and historical accounts, the theme exposes the practical difficulties friends face—such as hospital bureaucracy, workplace inflexibility, and legal invisibility—and advocates for new social and legal frameworks that formally recognize friendship caregiving. The emotional labor involved is complex and often fraught with self-doubt, yet deeply valuable, revealing friendship as an active practice grounded in ongoing effort, sacrifice, and emotional commitment rather than idealized perfection.

Class, Race, and Gender Among Friends

The history and experience of friendship are deeply intertwined with social identities such as class, race, and gender, shaping how friendships form, endure, and are perceived. The narrative brings to light stories of working-class and immigrant women whose friendships offered crucial survival and solidarity but were frequently marginalized or stigmatized by dominant culture and authorities as “bad company” or dangerous.

These friendships often operated as informal networks of economic support, legal aid, and emotional refuge within harsh urban environments, contradicting cultural assumptions about female sociability. Similarly, the erasure and difficulty in tracing the lives of women like Minerva Jones reflect how race and class invisibilize women’s friendships in historical records.

Gendered expectations around “femaleness” also impose constraints and judgments on friendships, particularly in professional or public spheres, where women must navigate vulnerability alongside rivalry and social scrutiny. The theme demonstrates that friendships do not exist in a vacuum but are shaped by power structures and social hierarchies, influencing the possibilities and limitations of connection, trust, and support.

Transition of Friendship From Youth to Midlife and Aging

The evolution of friendship across life stages reveals shifts in emotional intensity, purpose, and social context. Youthful friendships often carry a raw, rebellious energy that challenges domestic expectations and offers avenues for identity exploration and risk-taking.

These early bonds can be formative but are also subject to idealization and anxiety about “bad influences. ” As women move into adulthood and professional life, friendships become complicated by competition, gendered workplace dynamics, and the need to balance vulnerability with strategic self-presentation.

The narrative highlights the fragile and often awkward nature of forming and maintaining friendships in male-dominated environments where women’s sociability is policed. Later in life, friendship often re-emerges as a vital source of care and companionship, especially amid aging, illness, and social change.

Communal living arrangements and renewed bonds among older women illustrate a shift toward chosen families and intentional communities that provide mutual support and challenge isolation. This theme traces how friendships adapt to changing emotional needs and social roles, emphasizing that while the form and intensity of friendships may evolve, their importance persists throughout life.

Friendship and Cultural Mythology Versus Reality

The book critiques enduring cultural myths about friendship—particularly female friendship—that impose idealized or moralistic frameworks on how friendships should function. Historical accounts show that women’s friendships have long been viewed through suspicious or pathologizing lenses, associating intense emotional bonds with sexual deviance, moral danger, or social instability.

These myths have justified social control over women’s relationships and imposed rigid expectations that friendships must be either selfless or virtuous. Contrastingly, the lived reality of friendships includes ambivalence, rivalry, betrayal, and “bad friend” moments that defy neat categorization.

Contemporary media perpetuates this dualism by circulating “toxic friend” stereotypes, which can intensify feelings of shame and anxiety when friendships falter. By blending memoir with cultural critique, the text calls for dismantling these myths and embracing a more realistic, compassionate understanding of friendship as a messy, dynamic practice that requires flexibility, forgiveness, and acceptance of imperfection.

Friendship as Social Practice and Fluid Relationship

Friendship is depicted as an inherently fluid and ambiguous relationship that resists institutional codification or fixed roles. Unlike family or romantic ties, friendships lack formal obligations or clear rules, demanding continual invention, negotiation, and emotional labor to sustain.

This flexibility can be both liberating and challenging, requiring openness to change, vulnerability, and the acceptance that friendships may fade or transform over time. The author emphasizes the importance of seeing friendship as a practice rather than a static ideal, highlighting small everyday acts of care and the willingness to try again despite difficulties.

This perspective pushes against perfectionist or transactional views of friendship dominant in contemporary culture, which often prioritize convenience, self-care, or strategic benefits. Instead, the text proposes a vision of friendship that accepts “good enough” relationships as valuable and realistic, acknowledging that trust, loyalty, and connection are ongoing achievements shaped by individual and social contexts.

Friendship in Modern Social and Technological Contexts

The impact of modern social structures and technology on friendship forms a significant theme, exposing both opportunities and challenges. Workplace friendships illustrate the tension between emotional support and professional strategy, where women must manage the risks of gossip, rivalry, and sexualization.

Contemporary urban living, with its fragmentation of traditional communities, pushes many individuals to rely more heavily on friends for care and social connection, leading to new models like communal living among older women. Meanwhile, digital technologies both facilitate and complicate friendship by creating new spaces for connection but also risking superficiality and loneliness.

The emergence of AI companions and online interactions raises questions about the authenticity and emotional depth of modern friendships, especially for marginalized or isolated individuals. This theme situates friendship within the ongoing negotiation between tradition and innovation, intimacy and distance, highlighting how cultural and technological changes continuously reshape what it means to be a friend today.