Before We Were Innocent Summary, Characters and Themes

Before We Were Innocent by Ella Berman is a gripping, character-driven thriller that dives deep into the complexities of female friendship, betrayal, and the scars left by tragic events.

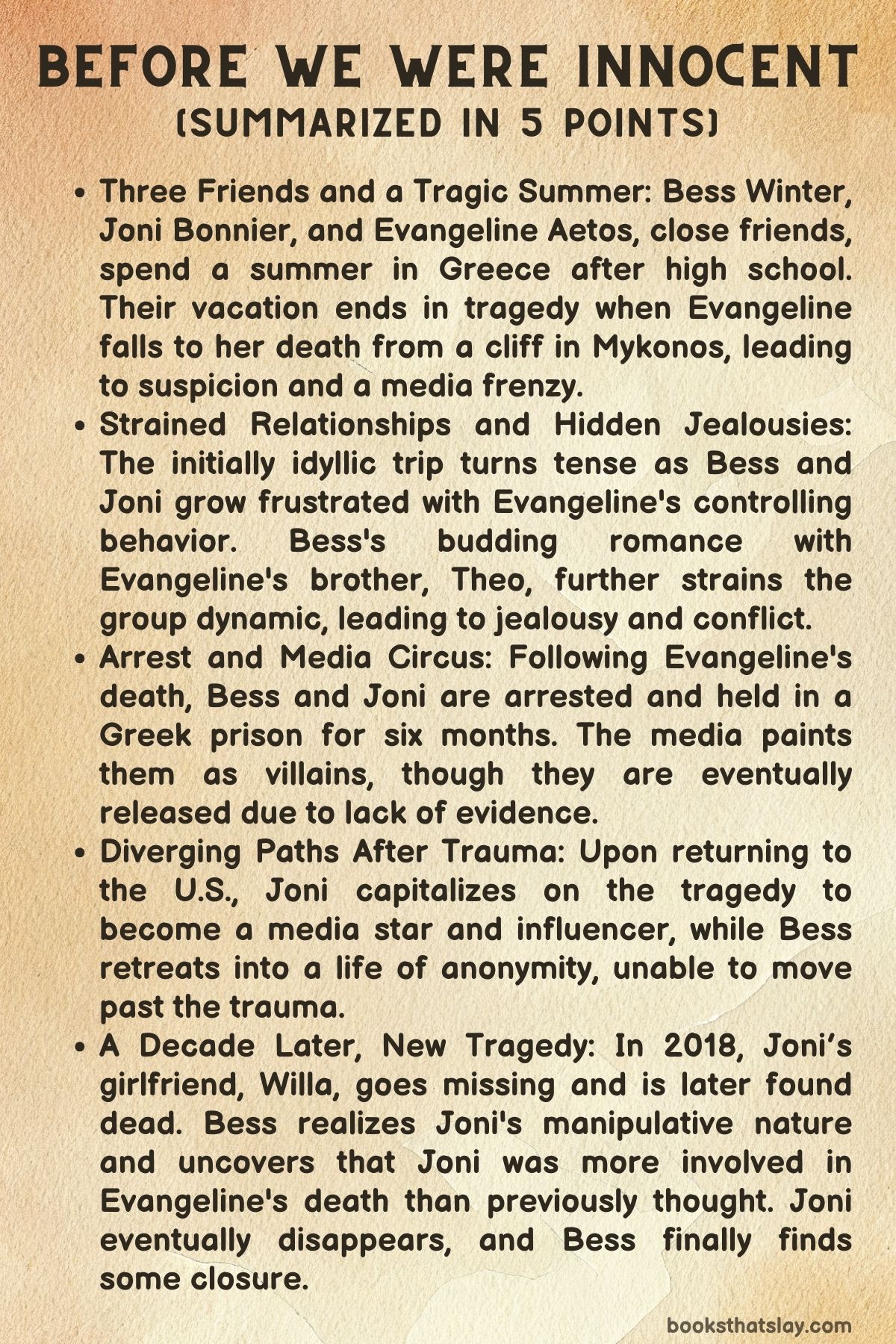

Through the dual timelines of a tragic summer in Greece and its echo a decade later, Berman deftly unravels how a single event can shape—and haunt—our lives. The story follows Bess, who is drawn back into the orbit of her estranged best friend Joni after years of silence, when echoes of their shared past resurface in the form of a new scandal. Tense, atmospheric, and psychologically astute, this novel interrogates truth, loyalty, and the stories women tell about themselves—and each other.

Summary

Bess, now living a solitary life near the stark, desolate Salton Sea in California, has built her existence around quiet routines and isolation. She works a mundane job moderating content on a dating app, avoids deep relationships, and keeps the world at arm’s length.

Her world is upended when Joni, a glamorous self-help influencer with a devoted following, reappears on her doorstep after a decade of estrangement. Their reunion is awkward and charged: Joni, whose life is carefully curated for public consumption, is suddenly in need.

She claims to need an alibi after a fraught encounter with her fiancée, Willa, who has since disappeared. The narrative toggles between this present-day crisis and the fateful summer of 2008, when Bess, Joni, and their effervescent friend Evangeline traveled to Greece on the cusp of adulthood.

The three girls, fresh from their privileged Calabasas high school, were intoxicated by freedom and possibility. Evangeline, whose wealth funded the trip, acted as ringleader, but their dynamic was volatile—Joni was brash and magnetic, Bess eager to belong, and Evangeline quietly desperate to hold their friendship together.

In Greece, their days blurred into sun-drenched afternoons and nights of partying with locals and fellow travelers. Beneath the glittering surface, rivalries and resentments simmered.

Joni and Bess grew closer—sometimes crossing the line between friendship and romance—while Evangeline became increasingly isolated. Small betrayals accumulated.

The girls’ carelessness and emotional turbulence built toward a tragic accident: Evangeline’s sudden death under ambiguous circumstances. The official story, constructed in panic and fear, was that she fell—a senseless accident, they insisted, fueled by alcohol and reckless youth.

Though the Greek authorities were unable to prove wrongdoing, the aftermath was devastating. Bess and Joni returned to California to a maelstrom of public scrutiny and media sensationalism.

Friends abandoned them; colleges rescinded offers. The world—hungry for a scandal—painted them as dangerous, manipulative girls.

While Bess retreated into herself, Joni forged ahead, eventually transforming their shared trauma into a redemption story. She wrote a bestselling memoir, became a sought-after speaker, and constructed a new identity as a survivor and inspiration.

A decade later, the wounds of that summer are reopened when Willa vanishes. Joni is once again at the center of a mystery, and Bess, out of loyalty or habit, agrees to provide her with an alibi, even as she doubts Joni’s honesty.

As detectives begin to circle, Bess is forced to relive the choices she made as a teenager, recognizing patterns of manipulation and complicity. The parallels between the two scandals—one past, one present—become inescapable.

Haunted by guilt and the knowledge that she has always been cast in someone else’s narrative, Bess begins to question her own version of the past. She reconnects with people who were affected by Evangeline’s death, including Evangeline’s brother, and starts to see the broader consequences of their silence.

Meanwhile, Joni’s media machine goes into overdrive, spinning Willa’s disappearance to her advantage, just as she once reframed the events in Greece. As the tension mounts, Bess is faced with an impossible choice: continue to protect Joni and repeat the mistakes of her youth, or break free from her former friend’s influence and risk exposing everything.

The story becomes not just about uncovering what happened to Willa, but about who gets to own the truth of the past, and whether redemption is ever possible for those who have lived in the shadow of a terrible secret.

Characters

Bess

Bess serves as the novel’s introspective and haunted narrator. She is deeply affected by the events of her youth and the choices she made in both the Greek summer and the present day.

Her personality is marked by passivity and a tendency to be led by stronger characters, especially Joni. Throughout the novel, Bess wrestles with feelings of guilt, shame, and complicity.

She is unable to fully extricate herself from the narrative that Joni creates but never quite believes in her own innocence either. Her journey is primarily one of self-discovery and gradual empowerment.

Bess learns to differentiate her own truth from the one imposed on her. Despite her apparent fragility, she demonstrates a subtle resilience.

As she ultimately chooses to claim agency over her own story, Bess rejects the manipulative dynamics that have long governed her life. Her relationship with guilt and memory is complex—she is both a victim and, in her silence and compliance, a participant in the moral ambiguities surrounding Evangeline’s death and Joni’s subsequent rise to fame.

In the end, Bess’s greatest act is not public vindication but private liberation. She steps out of Joni’s shadow and refuses to continue the cycles of cover-up and denial.

Joni

Joni is the charismatic and polarizing force at the heart of the novel. She is both admired and feared for her strength, ambition, and capacity for reinvention.

Her defining trait is a remarkable ability to control narratives—whether in the immediate aftermath of Evangeline’s death, in her public persona as a self-help influencer, or in her personal relationships. She is bold, unapologetic, and often ruthless.

Joni uses charm, manipulation, and emotional intelligence to achieve her goals. For her, vulnerability is a tool and guilt a story to be weaponized or rewritten as needed.

Even when confronted with evidence that should shatter her façade, Joni adapts and spins events to her advantage, always seeking the upper hand. Yet, beneath the surface, she is not simply a villain.

Her motivations are layered with her own wounds and a desperate need for control, perhaps stemming from insecurity and a fear of irrelevance. While she is capable of genuine emotion, her self-preservation instincts almost always win out.

Joni embodies the dangers of unchecked charisma and the cost of living by performance rather than truth. She ultimately stands as both a cautionary figure and a darkly compelling survivor.

Evangeline

Though Evangeline dies early in the story, she is a constant presence in both timelines. Her memory haunts Bess and shapes the moral universe of the novel.

Evangeline is initially depicted as generous, idealistic, and somewhat naive. She is the wealthy friend whose resources allow the trio to embark on their fateful Greek adventure.

She is eager to please and often acts as a peacekeeper. Beneath her surface warmth lies a deep vulnerability and a yearning to be truly seen and valued.

As tensions rise among the friends, Evangeline’s emotional fragility becomes more apparent. Her sense of exclusion and instability mounts until the night of her tragic death.

Evangeline’s story is ultimately one of erasure: in life, she struggles to assert herself against Joni and Bess’s intense connection. In death, she becomes a symbol and a tool in Joni’s rise to fame, her own truth obscured by the versions crafted by others.

Her tragedy is both personal and symbolic. She illustrates the dangers of being sidelined in one’s own narrative and the ease with which vulnerable people are rewritten by those with more power.

Willa

Willa appears mainly in the present-day timeline as Joni’s fiancée. She is a prominent activist with her own public persona.

Initially, she is a background figure, but her mysterious disappearance triggers the novel’s central crisis. Willa’s character is marked by a sharp awareness of image and boundaries.

She is willing to challenge Joni’s manipulations. Her decision to disappear is ultimately an act of protest against Joni’s hypocrisy, a dramatic way of reclaiming her own agency and exposing the cracks in Joni’s carefully curated façade.

Willa’s role, though less central than the trio’s, is crucial. She serves as a modern foil for both Joni and Bess, embodying the consequences of secrets and the power of refusing to play along with toxic dynamics.

Theo

Theo, Evangeline’s brother, is a minor but significant character who serves as a moral anchor in the present-day timeline. He has spent years processing the loss of his sister and the public spectacle that followed.

When he reconnects with Bess, their interaction is marked by a sense of quiet understanding and grief. Theo’s presence forces Bess to confront the reality of what happened in Greece and the broader impact of their actions.

He offers her a glimpse of forgiveness but also a reminder that some wounds cannot be healed by narrative alone. He represents the lives touched and altered by the trio’s choices and the lingering need for truth and closure.

Themes

Female Friendships

The central theme of Before We Were Innocent is the intricate and often tumultuous nature of female friendship. The novel delves deep into the emotional bonds between Bess, Joni, and Evangeline, exploring how their relationships are shaped by jealousy, loyalty, competition, and the desire for acceptance.

Berman portrays female friendship as both a source of strength and a potential pitfall. It is capable of fostering deep connections but also of breeding resentment and betrayal.

The dynamics between the three girls illustrate how power shifts within friendships can lead to destructive outcomes, particularly when one friend feels marginalized or overshadowed. The tragedy of Evangeline’s death becomes a catalyst that exposes the cracks in their friendship, ultimately leading to a complete unraveling of their relationships.

This theme is revisited in the 2018 timeline, where the lingering effects of the past continue to influence Bess and Joni. It highlights how unresolved tensions and guilt can haunt a person for years.

The Influence of Media and Public Perception

The novel critically examines the role of media in shaping public perception, particularly in cases involving young women. After Evangeline’s death, Bess and Joni become the subjects of intense media scrutiny, with their lives and characters dissected by journalists and the public alike.

This theme explores how the media often distorts the truth, creating narratives that are more sensational than factual. Bess and Joni are vilified, their private lives exposed and manipulated to fit a storyline that satisfies the public’s appetite for scandal.

Berman highlights the dangers of this kind of public shaming, where individuals are reduced to caricatures, and the complexities of their situations are ignored. The aftermath of this media frenzy has long-lasting effects on Bess, who retreats from the public eye, scarred by the experience.

In contrast, Joni uses the media to her advantage, rebranding herself as a survivor and capitalizing on the very system that once condemned her. This theme underscores the power of the media in constructing and deconstructing identities, especially for women.

Guilt and Responsibility

Guilt and responsibility are pervasive themes in the novel, particularly in relation to the events surrounding Evangeline’s death and the later disappearance of Willa. Bess is plagued by guilt, not only for what happened in Mykonos but also for her perceived role in Willa’s death.

This guilt is compounded by her realization that she may have been complicit in a lie that shaped the course of her life. The novel explores how guilt can distort one’s sense of reality, leading to self-doubt and a questioning of one’s moral integrity.

Bess’s struggle with guilt is contrasted with Joni’s seemingly untroubled conscience. While Joni appears to navigate life without being weighed down by the past, Bess’s guilt prevents her from moving forward.

The theme of responsibility is also examined through the characters’ actions and decisions, particularly in the way Joni manipulates situations to her advantage. Bess’s eventual discovery that Joni was present during Evangeline’s fall challenges her understanding of responsibility and forces her to reconsider the events of that fateful night.

The novel ultimately raises questions about who is responsible for the tragic outcomes and how much of that responsibility Bess and Joni must bear.

The Search for Identity

The theme of identity is central to the novel, particularly in the way the characters navigate their lives in the wake of trauma. Bess, Joni, and Evangeline are all at a crossroads in their lives, transitioning from adolescence to adulthood.

The trip to Greece represents a rite of passage, a final moment of freedom before they must confront the realities of their futures. However, the tragedy that unfolds forces each girl to reassess who they are and who they want to be.

For Bess, the experience is deeply disorienting, leading her to withdraw and lose her sense of self. Her identity becomes defined by the trauma and the media’s portrayal of her, leaving her struggling to reclaim her life.

In contrast, Joni takes control of her narrative, crafting a new identity for herself as a media influencer. This theme explores how identity can be shaped by external forces, such as societal expectations and public perception, as well as by internal struggles with guilt, responsibility, and self-worth.

The novel also touches on the idea of reinvention, as seen in Joni’s transformation, and the challenges that come with trying to forge a new identity in the shadow of past events.

Power and Manipulation

Power dynamics play a crucial role in Before We Were Innocent, particularly in the relationships between the characters. Evangeline’s controlling nature initially sets the tone for the girls’ interactions.

As the novel progresses, the power shifts, particularly between Bess and Joni. Joni’s ability to manipulate situations and people becomes more evident as the story unfolds, especially in her handling of the aftermath of Evangeline’s death and later, Willa’s disappearance.

This theme examines how power can corrupt relationships, leading to betrayal and moral compromise. Joni’s manipulation of Bess, both in the past and in the present, reveals the darker side of friendship and the lengths to which some will go to protect themselves or achieve their goals.

The novel also explores the power of storytelling, as Joni’s ability to control the narrative allows her to reshape her identity and influence others. Bess’s gradual realization of Joni’s manipulative tendencies forces her to confront the power imbalances in their friendship and to reclaim her own agency.

This theme highlights the complex interplay of power, manipulation, and control in human relationships, particularly among women.

Trauma and Healing

The novel deeply engages with the theme of trauma, particularly how it shapes the characters’ lives and their paths to healing. Bess’s trauma from Evangeline’s death and the subsequent media frenzy leaves her emotionally scarred, leading to a decade of withdrawal and avoidance.

Her journey throughout the novel is one of seeking closure and healing, as she grapples with her guilt and the lingering effects of the past. The novel portrays trauma as a powerful force that can define a person’s life, but also suggests that healing is possible, albeit difficult.

Bess’s eventual reconciliation with her past, marked by her final moments of closure with Theo and his wife, indicates that while trauma leaves a lasting impact, it does not have to dictate one’s future.

The theme of healing is contrasted with Joni’s approach to trauma, which is more about avoidance and reinvention rather than true emotional recovery. The novel suggests that healing requires confronting the past, accepting responsibility, and finding a way to move forward, even when the path is fraught with pain.