Bel Canto by Ann Patchett Summary, Characters and Themes

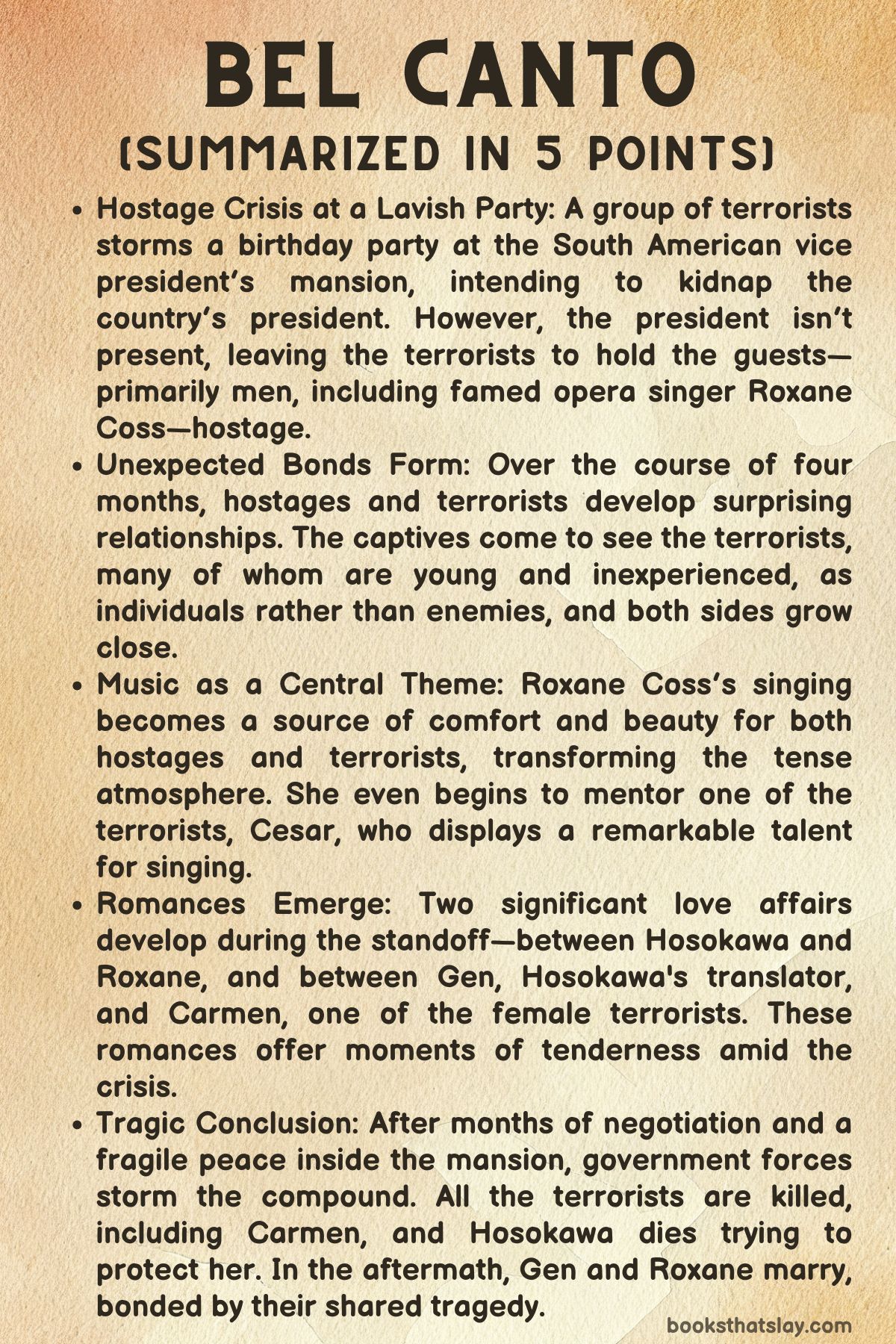

Bel Canto by Ann Patchett is a novel about an unexpected community formed during a hostage crisis at the vice president’s mansion in an unnamed South American country. The crisis begins when terrorists, aiming to capture the president, storm a lavish birthday party for Japanese businessman Katsumi Hosokawa.

The novel explores how music, especially the opera of renowned soprano Roxane Coss, fosters deep bonds between captors and captives. As days turn into months, the hostages and terrorists find love, understanding, and beauty in their shared experience, even as the looming threat of a violent resolution hovers over them all.

Summary

At the heart of Bel Canto, a group of people from different countries and backgrounds find themselves caught in an extraordinary situation when a birthday celebration turns into a hostage crisis.

Katsumi Hosokawa, a wealthy Japanese businessman, is the guest of honor at the party, which is hosted by the vice president of a South American country. Though Hosokawa has no interest in investing in the country as officials hope, he attends simply to hear Roxane Coss, an opera singer whose voice he deeply admires.

The evening is upended when a group of armed terrorists bursts in, intent on kidnapping the country’s president. However, their plan goes awry because the president isn’t at the event.

With no immediate solution, the terrorists improvise and take the entire party hostage. The next day, they begin releasing women and children, but they decide to keep the men and, crucially, Roxane Coss, believing her fame and influence could prove useful in negotiations.

As days pass, the tense situation starts to transform. The initial fear and uncertainty gradually give way to unexpected relationships.

The hostages begin to see their captors, many of whom are young and inexperienced, less as dangerous enemies and more as individuals with their own stories and vulnerabilities.

Among the hostages, Gen Watanabe, Hosokawa’s translator, becomes vital to communication as he speaks multiple languages and helps facilitate understanding between the terrorists and their captives.

One of the most remarkable changes comes through music. Roxane, who initially refuses to sing, eventually begins practicing daily. Her voice mesmerizes everyone, from the hostages to the terrorists.

Music becomes a source of comfort, bonding, and even joy for those trapped in the mansion. Soon, an unexpected discovery is made: Cesar, one of the young terrorists, has a stunning voice. Roxane starts to mentor him, teaching him to sing.

Amid the strange new normal that develops, romances blossom. Hosokawa and Roxane, united by their shared love of opera, begin a love affair. Meanwhile, Gen falls in love with Carmen, a female terrorist.

She asks him to teach her to read and write, but their lessons soon turn into secret romantic encounters. Other relationships form as well. The vice president, Ruben Iglesias, becomes attached to one of the young terrorists, Ishmael, and even dreams of adopting him.

Despite the growing closeness between the two sides, the hostages and terrorists know that their time together is temporary. Red Cross negotiator Joachim Messner warns the group that the government will eventually take action. After four months, that day arrives.

Government forces storm the mansion, killing all the terrorists, including Carmen.

Tragically, Hosokawa also dies, caught in the crossfire while trying to protect Carmen. In the aftermath, Gen and Roxane, having formed a bond through their shared ordeal, marry, carrying with them the memory of what they endured.

Characters

Katsumi Hosokawa

Katsumi Hosokawa is the head of the Japanese electronics corporation Nansei. He attends the party at the Vice President’s mansion as the guest of honor, but he is not there for business reasons.

Rather, his deep love for opera, particularly for the voice of soprano Roxanne Coss, drives him to attend the event. Hosokawa is depicted as a reserved and introverted man, someone who is not easily swayed by political or economic opportunities.

Throughout the novel, Hosokawa is a character whose quiet dignity and sense of honor emerge as a counterpoint to the violence and chaos of the hostage situation. His love affair with Roxanne Coss unfolds as a tender, genuine connection that transcends the tumult of their surroundings.

Though mostly passive and reflective, Hosokawa demonstrates a quiet courage and commitment, particularly in the tragic final moments when he sacrifices himself to protect Carmen. His personal journey is a profound one, where art, love, and mortality converge, making him one of the most sympathetic and tragic figures in the novel.

Roxanne Coss

Roxanne Coss is the world-famous opera soprano whose voice captivates not only Hosokawa but nearly everyone who hears her. At first, Roxanne’s character is portrayed as somewhat aloof and distant, accustomed to being the center of attention because of her celebrity.

However, as the novel progresses, her character deepens and softens, revealing her passion for music and her ability to affect and transform those around her. After her accompanist dies early in the crisis, she assumes a central role in the strange, enclosed world that develops in the mansion.

Her daily singing becomes a form of emotional and spiritual sustenance for both the hostages and the terrorists, bridging gaps between people from vastly different walks of life. Her relationship with Hosokawa is a touching, late-blooming love that grows amid the surreal circumstances.

Roxanne is shown as a woman capable of great vulnerability and affection. The juxtaposition of her artistic presence against the harshness of the hostage situation illustrates how beauty can exist even in the darkest of times.

Gen Watanabe

Gen Watanabe, Hosokawa’s personal translator, is one of the novel’s most essential characters. His fluency in multiple languages makes him indispensable during the hostage situation, allowing him to serve as a bridge between the hostages and terrorists.

Gen is resourceful, patient, and empathetic, handling the constant demands of his role with composure and grace. His role as translator gives him a unique position of power within the group, yet he remains humble and helpful throughout.

Gen’s romantic relationship with Carmen, a young female terrorist, adds complexity to his character. His love for Carmen represents a humanizing and transformative force in a time of crisis, as they teach each other to read and write, deepening their connection.

Unlike Hosokawa’s tragic love story, Gen survives the ordeal, and his eventual marriage to Roxanne Coss in the epilogue shows the lasting impact of their shared experience. Gen’s ability to navigate both the literal and metaphorical languages of the characters in Bel Canto makes him one of the most central figures in the narrative.

Carmen

Carmen is one of the terrorists, a young woman who initially hides her gender among the group of revolutionaries. Her character is defined by her sensitivity and her eagerness to learn.

Despite her role as a terrorist, Carmen is portrayed as an innocent figure, someone whose circumstances have led her into the group rather than any deep ideological commitment. Her relationship with Gen reveals a tender side of her, and their secret romance becomes a focal point of the novel.

Carmen’s desire to better herself, to learn to read and write, contrasts with her position as a hostage-taker, presenting her as a character torn between two worlds. Her tragic death at the end of the novel is a devastating blow, particularly for Gen.

She symbolizes the fragile line between hope and destruction that runs throughout the story. Carmen’s character embodies the idea that, despite one’s circumstances, the longing for personal growth and love is universal.

General Benjamin

General Benjamin is one of the leaders of the terrorist group. Though he initially comes across as a menacing figure, his character undergoes a transformation as the narrative progresses.

He represents the voice of authority among the terrorists, but his interactions with the hostages reveal his more human and vulnerable side. As time passes, General Benjamin begins to engage in mundane activities such as playing chess with Hosokawa, which humanizes him and blurs the line between captor and captive.

His stubbornness in refusing to surrender, despite Messner’s repeated warnings, highlights his desperation and fatalism. Benjamin’s eventual death, along with the other terrorists, is portrayed as both inevitable and tragic.

He becomes a victim of a struggle that has long since lost its original purpose.

Simon Thibault

Simon Thibault is a French diplomat and one of the hostages. His character is notable for his deep love for his wife, Edith, who is released early in the hostage situation.

Unlike many of the other hostages, Simon longs for the crisis to end so he can be reunited with her. His love for Edith is pure and constant, serving as a counterpoint to the more complicated relationships that develop during the crisis.

Thibault’s character highlights the theme of enduring love and devotion, even in the most difficult circumstances. His presence in the novel reminds the reader that the hostages have lives and relationships that are put on hold by the events taking place.

Despite his quiet demeanor, Simon’s love for his wife anchors him throughout the ordeal, providing an emotional depth to the story’s broader exploration of human connection.

Joachim Messner

Messner is the Red Cross negotiator who serves as the only regular link between the captives inside the mansion and the outside world. His character represents reason and diplomacy, as he constantly urges both sides to reach a peaceful resolution.

Despite his neutral position, Messner grows fond of both the hostages and the terrorists, which complicates his role. He is a pragmatic and weary figure, having seen similar situations in other parts of the world.

Messner’s warnings to General Benjamin about the inevitable military intervention are laced with a sense of tragic inevitability. His character embodies the futility of trying to mediate in a situation that is doomed from the start.

Yet he maintains his professional role, reflecting the novel’s exploration of human conflict and the limits of compassion in the face of intransigence.

Ruben Iglesias

Ruben Iglesias, the Vice President of the unnamed South American country, plays an important role in the novel. Initially a peripheral figure, Ruben transforms into a nurturing presence within the mansion.

He takes on the role of caretaker, tending to the house and garden and developing a paternal relationship with Ishmael, one of the young terrorists. His character highlights the theme of transformation.

Ruben moves from being a political figure to a more domestic, almost fatherly role. His care for Ishmael and his vision of adopting the boy symbolize the unexpected bonds that form during the crisis.

His character emphasizes the possibility of personal growth and redemption, even in the most dire circumstances.

Ishmael

Ishmael is one of the youngest terrorists, and his character represents the innocence and vulnerability of the younger revolutionaries. Despite his role as a gun-wielding captor, Ishmael’s youth and inexperience make him more of a victim of circumstance than a true terrorist.

His relationship with Ruben Iglesias, who envisions adopting him, is a touching element of the story. Ishmael’s character reflects the novel’s larger theme of the blurred lines between victim and perpetrator.

He is both a child caught up in political violence and a figure capable of forming genuine bonds with the hostages. His tragic end underscores the loss of potential and the senselessness of the violence that ultimately claims the lives of the terrorists.

Cesar

Cesar is another young terrorist who reveals unexpected talents during the course of the novel. His ability to mimic Roxanne’s singing astonishes the hostages, and Roxanne eventually takes him under her wing as a student.

Cesar’s character illustrates the transformative power of art, as his talent for singing offers a glimpse of a different life he could have led under different circumstances. Like many of the other young terrorists, Cesar’s death in the final assault is a poignant reminder of the wasted potential.

His relationship with Roxanne highlights the novel’s central theme of music as a unifying and redemptive force.

Themes

The Nature of Power, Politics, and Class Conflict in a Contingent Society

Ann Patchett’s Bel Canto delves deeply into the intersection of power, politics, and class dynamics, unraveling these themes within the microcosm of the hostage crisis. The terrorists, many of whom are young, indigenous teenagers, come from an impoverished, marginalized background, while the hostages are largely wealthy and influential figures from the international elite.

The novel presents the tension between these two worlds, showcasing how class disparities create a situation where violence becomes the language of the powerless. The terrorists, driven by political and economic disenfranchisement, represent the excluded underclass, demanding justice for the working poor and political prisoners.

This setup contrasts starkly with the privileged lives of the hostages, who, although confined, continue to enjoy certain luxuries and privileges, such as opera performances and chess games. The class disparities within the mansion reveal how power operates in hidden, often subtle ways: through wealth, culture, and even language.

Gen Watanabe, for instance, holds a central role because of his ability to communicate across languages, reflecting how mastery over language—both literally and metaphorically—can consolidate influence. Yet, as time passes, the stark boundaries of class, politics, and power blur, with hostages and terrorists bonding and sharing in cultural exchanges.

This shift highlights a deeper commentary on the fluidity of power, suggesting that, in extreme circumstances, social hierarchies can be both reinforced and dismantled.

The Transformative Power of Art and Music in Human Connection

At the heart of Bel Canto lies an exploration of art—particularly music—as a transformative force capable of bridging divides, dissolving hostilities, and fostering deep human connections. The opera singer Roxanne Coss becomes a symbol of this transcendental power.

Her voice captivates both hostages and terrorists alike, becoming a shared source of beauty that transcends the fear, violence, and political motivations that initially dominate the situation. Music becomes more than mere entertainment; it is a shared, almost sacred experience that unites disparate individuals across cultural, economic, and political boundaries.

The daily singing sessions shift the tone of the captivity from one of anxiety and suspicion to a collective experience of grace and reflection. This transformation speaks to the capacity of art to transcend even the most hostile environments, forging empathy and mutual recognition between people who might otherwise remain forever opposed.

The novel suggests that art has an elemental, almost redemptive role in human life, capable of opening up avenues of understanding and peace that logic, negotiation, or political maneuvering cannot achieve.

The Erosion of Identity and the Fluidity of Roles in a Prolonged Crisis

Over the course of the four-month standoff, Bel Canto examines how individuals’ identities begin to shift as they adapt to an extraordinary and prolonged crisis. The hostage-takers, initially defined by their roles as armed insurgents, gradually shed their hardened exteriors as they interact more closely with the hostages.

Leaders like General Benjamin become more humanized, engaging in mundane activities like playing chess, while younger terrorists, like Carmen and Ishmael, reveal their vulnerabilities and aspirations. In a parallel sense, the hostages evolve beyond their initial identities as well.

Ruben Iglesias, the Vice President, sheds his political persona, becoming more of a caretaker for the mansion and its garden. Katsumi Hosokawa, a reserved businessman, becomes deeply involved in a passionate love affair with Roxanne.

The power dynamics between captors and captives blur as personal relationships form, with everyone assuming different roles—students, teachers, lovers, and friends. The rigidity of identity and social roles that existed outside the mansion dissolves, revealing a more fluid human nature under the pressure of confinement.

The Temporary Utopia and Its Inevitability of Destruction

Patchett’s novel presents the hostage situation as a kind of bizarre, temporary utopia, where the pressures of the outside world are suspended. This isolation allows for an idyllic coexistence between captors and captives.

Music and beauty become central to their shared experience, and cultural, economic, and political differences seem to fade as everyone finds solace in their shared confinement. Yet, this utopia is inherently fragile and doomed from the outset.

The novel hints early on that the terrorists will not survive, setting up the tragedy of a world built on temporary, artificial circumstances. The dream-like state in which captives and captors find themselves is unsustainable because it exists in opposition to the harsh political realities waiting outside the mansion.

The longer they remain together, the more they fear the inevitable end, knowing that their delicate world will be shattered by violence. This theme emphasizes the transitory nature of human connection in the face of broader political and social structures, which ultimately reassert themselves in the most brutal manner.

The Inescapability of Fate and Human Vulnerability in the Face of Uncontrollable Forces

Throughout Bel Canto, the characters struggle with a sense of helplessness against forces much larger than themselves. This underscores a key theme of the novel: the inescapability of fate and the vulnerability of human life.

The initial hostage crisis, triggered by a mistake (the president’s absence), already suggests how uncontrollable events can shape lives in unintended ways. From that point on, the hostages and terrorists alike are caught in a situation where their destinies are governed by external political machinations.

Despite their desires and relationships, they are all aware of the inevitability of a violent resolution. This theme is echoed by Messner, the Red Cross negotiator, who repeatedly vocalizes the reality that they are powerless to stop what is coming.

Even as bonds form and life inside the mansion takes on a semblance of normalcy, a current of fatalism persists, reminding the characters that they are all powerless in the face of larger, uncontrollable forces. The novel’s conclusion, where none of the terrorists survive and even Hosokawa is killed, reinforces this meditation on human vulnerability.