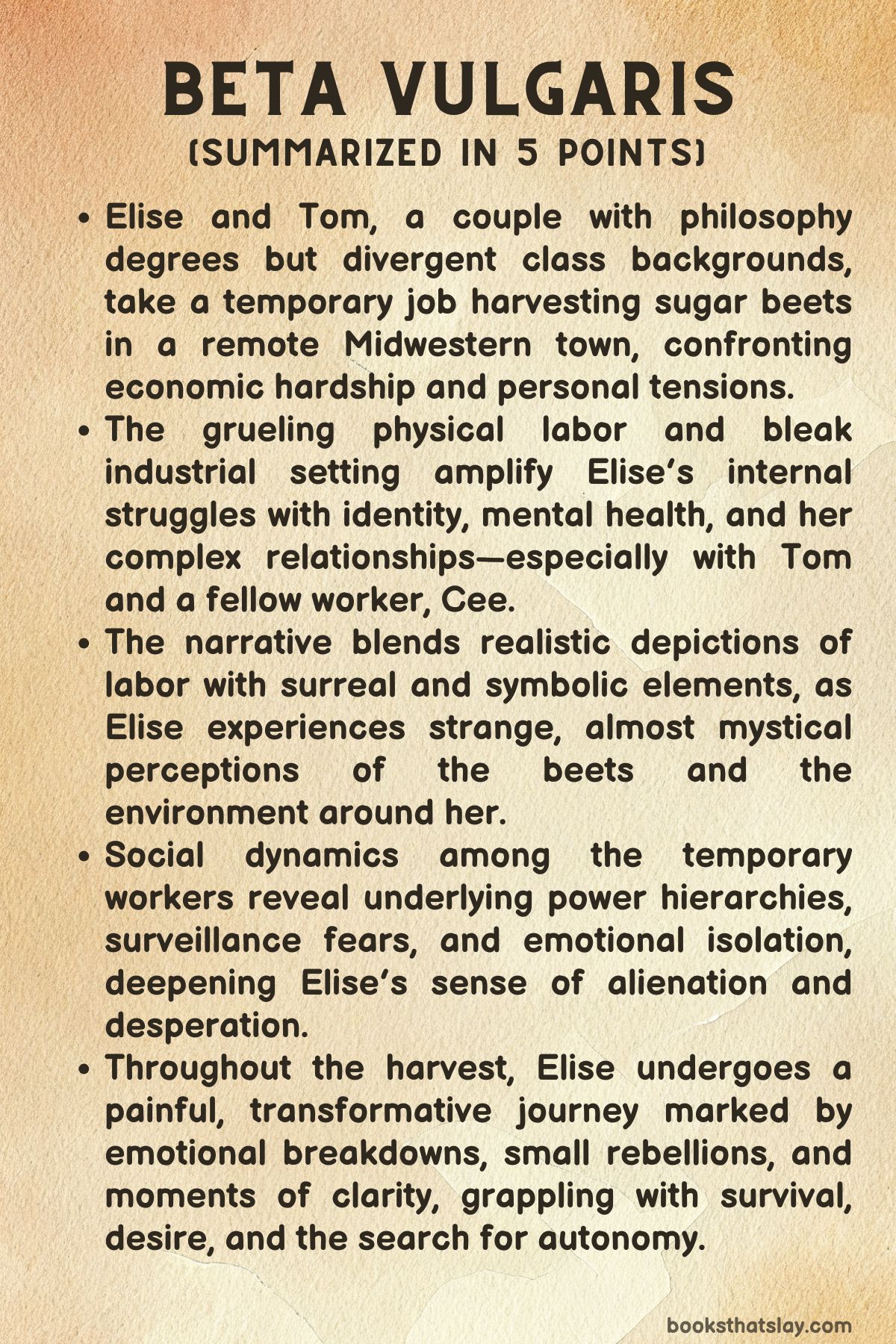

Beta Vulgaris Summary, Characters and Themes

Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield is a gritty, introspective novel that delves deep into the emotional and physical toll of seasonal labor in America.

Set against the backdrop of the sugar beet harvest in the rural Midwest, it follows Elise and Tom, a young couple navigating economic precarity and strained relationships while trapped in a demanding and alienating work environment. The novel blends realism with surreal and symbolic elements, exploring themes of class, identity, mental health, and the complex dynamics of human connection under pressure. Through Elise’s eyes, we witness a haunting, sometimes unsettling journey of survival, self-discovery, and quiet resistance.

Summary

Elise and Tom, a couple from Brooklyn with philosophy degrees but limited career prospects, take on seasonal work harvesting sugar beets in Minnesota. Their journey begins with a grim motel stay in Wisconsin, where financial tensions simmer beneath their interactions.

Elise, who feels increasingly reliant on Tom’s family wealth—though he refuses to tap into it—wrestles with her sense of independence and inadequacy. The small town of Robber’s Bluff, dominated by the beet processing plant, feels harsh and unwelcoming, yet it becomes the stage for their tentative attempt to make ends meet.

Settling into a campground for the transient workforce, Elise and Tom encounter a diverse but fractured community of laborers, largely white and varied in age.

Elise finds herself drawn to Cee, a confident and magnetic woman within the group, sparking a confusion of feelings that challenge her understanding of herself and her relationship with Tom.

The work is grueling, monotonous, and physically demanding, involving long night shifts where the cold and exhaustion wear down both body and spirit. As the harvest progresses, Elise’s mental and physical health begin to unravel.

She experiences dissociation, strange visions, and eerie sensations that blur the line between reality and hallucination—most notably, a growing perception of the beets as sentient or ominously alive.

These surreal moments intensify a sense of alienation and psychological strain, underscoring the brutal, dehumanizing nature of the labor and environment.

Meanwhile, Tom excels in his operational role, gaining recognition and becoming emotionally distant from Elise. Their relationship frays under the weight of unspoken resentments, class tensions, and divergent coping mechanisms.

Elise’s attraction to Cee deepens, leading to emotionally intimate but ultimately fraught interactions, further complicating her inner turmoil. The campground community itself is tense and suspicious, with rumors of surveillance and secret firings creating a climate of paranoia.

Minor conflicts and power dynamics among the workers mirror larger societal hierarchies, revealing the precariousness of their shared existence. Elise finds herself caught between isolation and a desperate need for connection, oscillating between moments of defiant rebellion and crushing exhaustion.

Elise’s physical state deteriorates as she pushes through pain and fatigue, ignoring warning signs of malnutrition and illness. Her body becomes a battleground for the psychological horrors she endures—hallucinations of infestation, bodily decay, and even fainting spells punctuate her daily routine.

The relentless work and emotional strain culminate in crises: an overdose in the camp, a fellow worker’s mysterious death, and her own near-collapse force her to confront the fragility of her situation. Throughout this ordeal, Elise is haunted by symbolic imagery—the recurring cryptic signs about “listening to the beets,” coworkers speaking in riddles, and surreal hallucinations that evoke themes of exploitation, consumption, and spiritual desolation.

The narrative increasingly adopts a nightmarish tone, blending the grotesque with the mundane, reflecting the psychological toll of poverty and labor under late capitalism. As the harvest nears its end, Elise faces the collapse of her relationships.

Tom’s departure for a privileged legal internship signals the quiet dissolution of their partnership. A bittersweet farewell with Cee closes another door, leaving Elise more isolated but also oddly resolute.

Despite her battered body and uncertain future, she begins to envision possibilities beyond survival—considering healthcare, education, and reclaiming autonomy. The final night shift becomes a cathartic, surreal rite of passage.

Alone atop the beet pile, Elise confronts the monstrous harvest and her own sense of self, shouting into the cold wind not in despair, but in a raw, liberated scream. When the work concludes, she boards a bus alone, wounded but alive, stepping into a future undefined but charged with a newfound determination.

The novel closes on this note of ambiguous rebirth—a testament to endurance, self-awareness, and the refusal to be consumed by the oppressive forces symbolized by the beet fields.

Characters

Elise

Elise is the novel’s central figure, whose internal and external struggles drive much of the narrative. She is a philosophy graduate who, despite her academic background, finds herself adrift in a transient, physically grueling job far removed from her previous life in Brooklyn.

Financial insecurity weighs heavily on her, compounding her existential doubts and feelings of inadequacy. Throughout the story, Elise’s character arc reveals a profound emotional and psychological unraveling as she grapples with the alienation and physical hardship of laboring in the beet harvest.

Her fluctuating relationship with Tom and growing emotional fascination with Cee highlight her complex identity, including her bisexuality and desire for connection beyond conventional boundaries. Elise’s body becomes a site of rebellion and deterioration, symbolizing her fractured psyche.

Yet, by the novel’s end, she emerges with a fragile sense of resolve and self-recognition, choosing to listen to herself rather than the dehumanizing “beets,” signaling a tentative but vital step toward reclaiming agency.

Tom

Tom functions as both a partner to Elise and a foil highlighting the themes of privilege and emotional distance. Like Elise, he holds a philosophy degree but represents a more stable, practical trajectory, aiming for law school and possessing access to family wealth, which he refuses to use fully.

His competence in the beet harvest contrasts sharply with Elise’s struggles, deepening the emotional rift between them. Tom’s growing withdrawal and inability to communicate honestly with Elise exacerbate her isolation.

However, his own vulnerabilities surface, particularly his feelings of being constrained by his socioeconomic status—expected not to complain or show weakness due to his privilege. His eventual decision to leave early for a legal internship marks the dissolution of their co-dependent relationship and underscores the divide between survival and aspiration within the couple.

Cee

Cee is a magnetic and resilient presence in the worker community, representing a different model of strength and survival within the harsh environment. Her charismatic demeanor and ease among the workampers contrast with Elise’s discomfort and insecurity.

Cee’s candidness about her past traumas and emotional boundaries creates a nuanced and complicated dynamic with Elise, blending intimacy, attraction, and tension. She becomes a catalyst for Elise’s self-exploration, particularly in relation to her bisexuality and longing for alternative forms of connection.

Despite this closeness, Cee maintains her independence, gently rebuffing Elise’s deeper emotional overtures and setting clear limits, which contribute to Elise’s internal conflict and feelings of rejection.

Themes

Psychological and Existential Impact of Dehumanizing Labor in Late Capitalist Structures

Beta Vulgaris immerses readers into the brutal physicality and mental toll of monotonous, grueling labor within a capitalist agricultural setting. Elise’s experience in the sugar beet harvest is emblematic of the way industrial labor reduces the human body and spirit to mere cogs in a mechanized, profit-driven machine.

The narrative explores how repetitive, exhausting work induces not only physical deterioration but also mental fragmentation—manifesting in Elise’s dissociation, fatigue-induced hallucinations, and surreal perceptions of the beets as sentient entities. This theme interrogates the alienation and bodily rebellion workers endure, exposing how economic necessity traps individuals in cycles of self-neglect and psychological unraveling.

The symbolic beet pile transforms into a monstrous monument, a corporeal and spiritual weight that threatens to crush Elise’s identity, illustrating how capitalist labor exploits and consumes the very beings it depends upon.

Class Anxiety, Privilege, and Emotional Disconnection Within Intimate Relationships

The novel intricately dissects the fissures wrought by class and economic disparity, especially within intimate partnerships. Elise and Tom’s relationship operates as a microcosm of these tensions.

Tom’s concealed family wealth and privileged background juxtaposed with Elise’s precarious financial reality foment emotional distance and resentment. Their interactions reveal the psychological burden of navigating inequitable economic power, where money—and the choices it affords—becomes both a weapon and a barrier to genuine empathy.

Tom’s internalized pressure to suppress vulnerability contrasts with Elise’s raw exposure to precarity, fostering mutual misunderstanding. This theme extends into the broader social context, reflecting on how capitalist privilege shapes emotional availability, communication, and personal identity, complicating notions of love and solidarity under strain.

Fluidity and Ambiguity of Desire, Identity, and the Search for Connection Amidst Marginalization

Elise’s growing emotional and possibly romantic fascination with Cee introduces a layered exploration of bisexuality, intimacy, and the yearning for meaningful connection outside heteronormative and class-defined constraints. This theme transcends simple coming-of-age or identity affirmation stories by embedding Elise’s desires within a context of economic hardship and emotional fragmentation.

The tension between attraction and rejection, openness and guardedness, underscores the vulnerability involved in forging alternative bonds amidst unstable environments. Their interaction encapsulates the broader quest for belonging and self-definition, complicated by past traumas, societal expectations, and the isolating conditions of the work camp.

The novel thus meditates on how desire and identity are negotiated in liminal spaces of marginalization, where love is both a potential refuge and a source of further emotional complexity.

Use of Surreal and Grotesque Symbolism to Illuminate Capitalist Exploitation and Psychological Disintegration

A pervasive theme throughout Beta Vulgaris is the novel’s surrealist layering, where the mundane horrors of labor are refracted through grotesque and almost mystical imagery. The beets, initially an agricultural commodity, take on unsettling, sentient qualities—pulsing, bleeding, whispering—blurring the line between external reality and internal psychosis.

This motif functions as an extended metaphor for the insidious nature of capitalist exploitation: the “living” beet pile symbolizes the omnipresent, almost supernatural force of economic oppression that invades mind and body. The uncanny moments, fever dreams, and body horror sequences deepen the narrative’s critique of late capitalism’s capacity to erode not only physical health but also mental coherence and spiritual wholeness.

The surrealism challenges readers to confront the invisible violence embedded in everyday labor and to question the boundaries of sanity within oppressive systems.

The Fragmentation and Reconstruction of Selfhood Amidst Crisis, Trauma, and Survival

Elise’s journey is ultimately one of fragmentation and tentative reconstruction—a prolonged liminal state where her identity, ambitions, and relationships splinter under external pressures and internal despair. The novel traces this psychological disintegration with unflinching detail: emotional numbness, dissociation, paranoia, and bodily obsession are markers of Elise’s crisis.

Yet, the narrative also charts moments of lucidity and resolve, suggesting that survival demands both confrontation with and adaptation to trauma. This theme grapples with the complexity of healing as a nonlinear process, rejecting facile redemption in favor of a raw, ongoing reckoning with pain and loss.

Elise’s final acts of defiance and refusal to “listen to the beets” symbolize a rebirth into self-awareness and autonomy, even amid persistent uncertainty. This nuanced portrayal of identity underscores how human beings negotiate continuity and change under duress, finding agency in imperfection and impermanence.