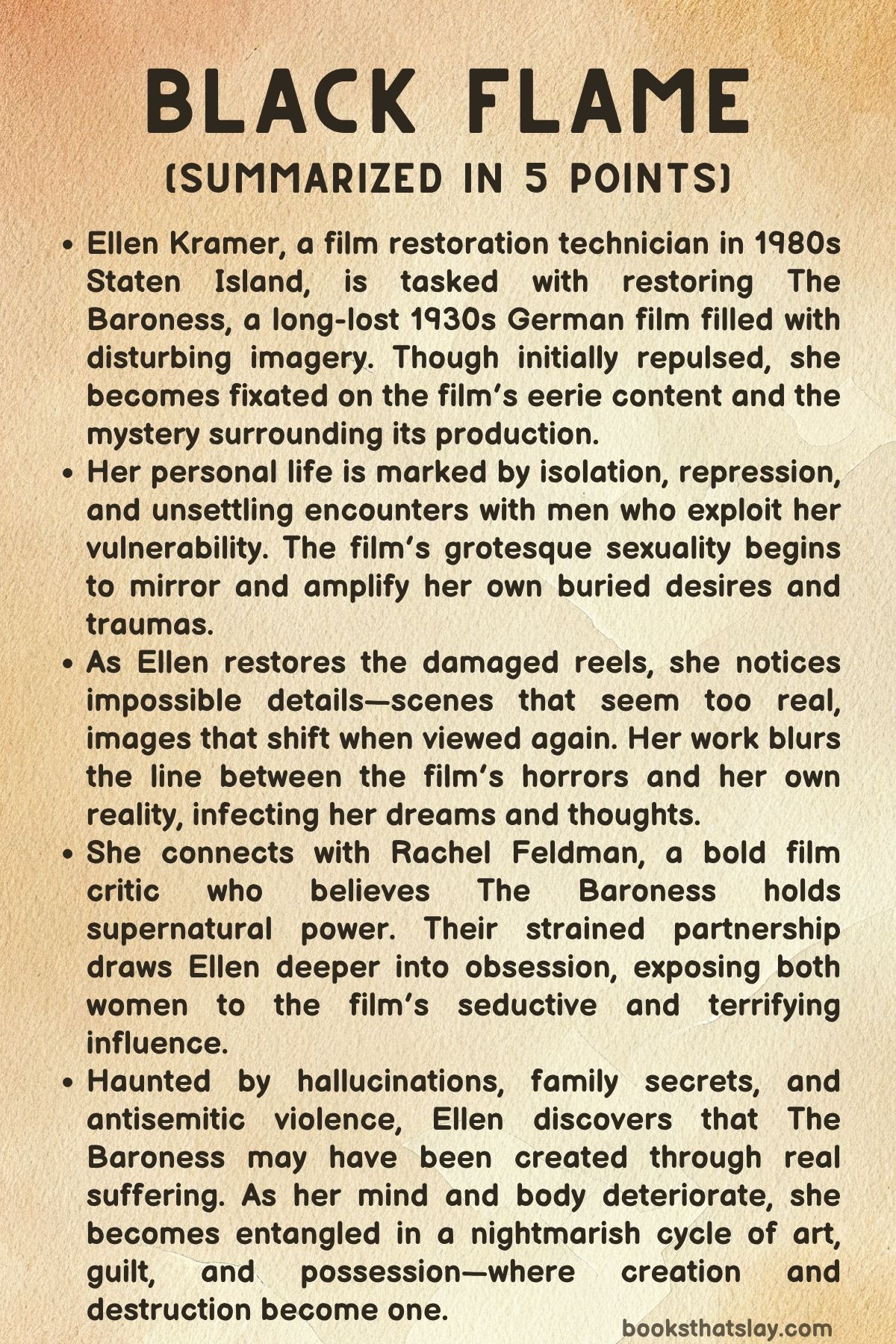

Black Flame Summary, Characters and Themes | Gretchen Felker-Martin

Black Flame by Gretchen Felker-Martin is a horror novel that explores the intersection of art, trauma, sexuality, and evil through the decaying lens of cinema. Set in the 1980s, it follows Ellen Kramer, a film restoration technician who becomes entangled with a cursed 1930s German film titled The Baroness.

As Ellen restores the reels, she is drawn into a nightmare of obsession, violence, and supernatural corruption that blurs the line between reality and film. Felker-Martin delivers a haunting story about repression, guilt, and the monstrous power of art to resurrect the past and consume the living.

Summary

Ellen Kramer works as a film restoration technician at the struggling Path Foundation in Staten Island in 1985. Her monotonous life takes a dark turn when she is assigned to restore The Baroness, a long-lost 1930s German film notorious for its disturbing imagery.

The project is initiated by Josef Haas, a representative from a Berlin film institute, and Willa Katz, a relative of the film’s director, Karla Bartok. The Path Foundation’s director, William Shrier, initially resists the project due to recent controversies but accepts after Katz offers a million-dollar deal.

Ellen, though deeply unsettled by the film’s grotesque and sexual content, is tasked with leading the restoration.

Ellen’s personal life mirrors the repression she feels at work. Her relationship with her conservative parents is distant, and a forced romance with Jesse Cavill, arranged through her mother, ends in empty, mechanical intimacy.

Ellen’s memories of a past lover, Freddie, a woman she abandoned out of shame, linger painfully. Her daily routine revolves around meticulous restoration work and brief encounters with a homeless amputee named Molly.

When Ellen begins examining The Baroness, she cuts her hand on the damaged celluloid, an injury that seems to awaken something inside her and within the film itself.

The film’s imagery begins to intrude on Ellen’s waking life. The negative shows details that appear disturbingly real—buildings too intricate to be sets, expressions too vivid to be acted.

Her nights fill with nightmares of occult rituals and mutilation, dominated by the terrifying figure of the Baroness. Her sense of time and self erodes; she finds notes in her handwriting she does not remember writing and begins hearing voices echoing lines from the film.

Her illness and fever worsen, and her perception of reality becomes increasingly unstable. Jesse forces himself upon her in a night of violence, after which she wakes to find blood and confusion surrounding her, unsure what is real and what belongs to the cursed world of the film.

Amid her breakdown, Ellen meets Rachel Feldman, a bold and provocative film critic who challenges Ellen’s beliefs about morality, identity, and art. Their relationship begins with hostility but evolves into an uneasy fascination.

Rachel believes that Bartok, the film’s director, made two versions of The Baroness: one conventional and one supernatural, containing impossible visual effects. She suggests Ellen’s version is the latter.

Despite her fear, Ellen screens the restored film privately for Rachel. During the screening, the images defy physical possibility—the camera movements, lighting, and realism exceed 1930s technology.

As they watch, Ellen feels an invisible force touch her while Rachel witnesses an unknown man’s ghostly presence. The women leave shaken and aroused, their experience defying rational explanation.

Ellen returns home to find her apartment ransacked and drenched in blood. The Baroness appears before her, smiling as if alive.

Her world collapses further when she discovers news that a former SS officer, Ernst Harald Schlemecher, was found in Berlin with a reel of The Baroness lodged in his throat. Ellen feels a chilling connection between his death and the film she is restoring.

Strange voices follow her, and she becomes convinced that the film carries not only demonic energy but also the spirits of its murdered cast and creator.

A hospital contacts Ellen to care for Molly, who has fallen ill with pneumonia. Ellen takes her in but soon faces terrifying hallucinations—visions of the Baroness demanding a sacrifice.

The haunting intensifies as Ellen’s infected hand begins to pulse with movement. One night, the reel itself comes alive, slithering into her wound and merging with her flesh.

Through this agony, Ellen experiences visions of Karla Bartok’s tragic life: a Jewish cabaret artist in Weimar Germany whose lover Ilya was murdered by fascists. Bartok, devastated, sought forbidden knowledge through the “Black Flame,” a ritual meant to fuse art with eternal suffering.

When the Nazis came for him, he bound the film with his own blood and the souls of the dead.

When Ellen awakens, her coworker Phillip finds her in shock. After glimpsing the horror attached to her, he gouges out his own eyes and kills himself.

Police question Ellen, but she barely comprehends what has happened. She isolates herself, caring for Molly while feeling the film’s infection spreading within her.

Desperate for guidance, she visits a Jewish cemetery, where the ghosts of Holocaust victims seem to stare through her. Their silent judgment drives her into deeper despair.

Seeking comfort, Ellen reconnects with Rachel, who cuts her hair and rekindles their intimacy. Their encounter, however, dissolves into hallucinatory terror as Rachel disappears mid-act, leaving Ellen alone and bleeding.

Meanwhile, Ellen’s boss, Shrier, prepares a public screening of The Baroness to regain the Foundation’s reputation. Ellen suggests inviting Silas Graham, a notorious televangelist, to frame the film as anti-Satanic propaganda.

Shrier agrees, unaware of the danger.

At her father’s retirement party, Ellen learns a devastating family secret: her grandmother collaborated with Nazis, betraying other Jews during the Holocaust. Her father, unable to bear the revelation, drunkenly sets himself on fire before the guests.

Ellen’s mother denies everything and disowns her, driving Ellen further toward collapse. A demonic figure resembling a nun appears, and Ellen flees home with Jesse, the man who once violated her.

This time, Ellen turns the tables—she tricks him into entering a closet that opens into a realm resembling the film’s world. Screams echo as unseen creatures drag him away.

With Jesse gone and Molly vanished, Ellen calmly prepares for the screening. She pays her rent in advance, smokes a borrowed cigarette from a passing comedian, and walks to the theater.

As the audience of wealthy donors, politicians, and clergy gather, Graham begins his sermon against corruption and sin. Ellen loads the cursed reel into the projector.

As the lights dim, her infected hand bursts open, spilling living film that merges with the machinery. The screen tears apart, and the figures of The Baroness step into reality—the armored Baroness, her servants, and the undead cast.

They massacre the audience in an inferno of blood and fire.

In the chaos, Ellen meets the Baroness face-to-face. The monstrous woman praises her as a successor.

Transported into the infernal world of the film, Ellen stands before the burning castle and sacrifices Jesse, his blood feeding the resurrected dead. Rachel appears briefly, marking Ellen with flame as the crowd chants a new name—Benjamin.

In that moment, Ellen is reborn, consumed by the demonic force that binds film, flesh, and memory together.

When the fire dies, the theater stands silent. The reel winds to an end, sealing itself shut.

The cursed film Black Flame has completed its final performance, leaving only darkness in its wake.

Characters

Ellen Kramer

Ellen Kramer stands at the core of Black Flame, embodying the intersection between trauma, repression, and the supernatural infection of art. She begins as a meticulous film restoration technician—precise, solitary, and emotionally stunted.

Her work serves as both sanctuary and torment: repairing fragile images mirrors her unconscious desire to repair her own fragmented identity. Haunted by internalized shame over her sexuality and memories of her failed relationship with Freddie, Ellen drifts through life in a haze of self-loathing and numbness.

As she restores The Baroness, the boundaries between the decaying film and her deteriorating psyche dissolve. The cursed nitrate seems to animate her suppressed desires and guilt, manifesting as physical sickness, hallucinations, and possession.

By the novel’s end, Ellen’s transformation is complete: she becomes both vessel and victim of the demonic force within the film. Her final acceptance of the Baroness’s dark power represents both liberation from repression and total surrender to madness, blurring the line between feminist awakening and apocalyptic self-annihilation.

The Baroness

The titular Baroness is less a character than a force—an embodiment of lust, power, and vengeance that transcends mortality. Originating from Karla Bartok’s forbidden 1930s film, she is at once a cinematic creation and a demonic entity sustained by violence and desire.

On screen she performs acts of sexual dominance and ritual murder; off screen she seeps into Ellen’s reality, feeding on guilt and suppressed passion. The Baroness functions as Ellen’s dark mirror, exposing the grotesque beauty of her buried rage and queerness.

Her presence fuses fascist aesthetics, religious blasphemy, and erotic energy, making her both the artistic pinnacle and moral corruption of Bartok’s vision. In the novel’s climax, she becomes the midwife of Ellen’s transformation, guiding her through blood toward transcendence.

The Baroness thus symbolizes the horror of absolute freedom—where creation, destruction, and desire are indistinguishable.

Karla Bartok

Karla Bartok, the long-dead director of The Baroness, haunts the novel as an artist consumed by grief and ambition. A Weimar-era Jewish cabaret visionary, Bartok’s life collapses under fascism’s rise and the murder of her lover, Ilya.

Her descent into occultism and madness leads her to bind her film to a demonic power, ensuring its survival beyond death. Bartok embodies the artist as necromancer—someone willing to sacrifice body and soul to make beauty immortal.

Through Ellen’s visions, Bartok’s story reflects the terrible cost of art that refuses to die: the film’s cursed immortality parallels the persistence of trauma and historical evil. She represents the merging of political horror with artistic obsession, showing how creation, under oppression, becomes indistinguishable from blasphemy.

Rachel Feldman

Rachel Feldman is Ellen’s intellectual and emotional foil—a confident, abrasive film critic who represents everything Ellen represses. She is open about her sexuality, cynical about morality, and fascinated by art’s capacity for transgression.

Rachel’s relationship with Ellen oscillates between seduction, rivalry, and pity. Her belief in The Baroness’ supernatural authenticity draws her into Ellen’s nightmare, but unlike Ellen, she views the horror with awe rather than fear.

Rachel becomes both tempter and witness, pushing Ellen toward confrontation with her buried desires. Their sexual and intellectual tension culminates in the film’s private screening, where both experience ecstasy and terror.

Rachel’s later denial of the supernatural marks her as the rational survivor—yet her final reappearance in the infernal world suggests complicity in Ellen’s damnation.

Jesse Cavill

Jesse Cavill epitomizes the banality of patriarchal control. Awkward, emotionally fragile, yet entitled, he represents the dull, coercive normalcy Ellen’s family demands she accept.

His sexual encounters with Ellen are joyless and invasive, reflecting her alienation from heterosexual norms. As the story progresses, Jesse transforms from a pitiful suitor into a grotesque symbol of domination and abuse.

Ellen’s eventual act of vengeance—feeding him to the otherworldly forces within The Baroness—is both revenge and rebirth. Jesse’s fate mirrors Ellen’s moral collapse, but also her rejection of passive suffering; his death seals her initiation into the film’s demonic covenant.

William Shrier

William Shrier, the opportunistic director of the Path Foundation, personifies hypocrisy within the cultural institutions that claim to preserve history. He is a bureaucrat who cloaks greed in moral rhetoric, eager to exploit controversy for funding while feigning virtue.

His treatment of Ellen—condescending, dismissive, and manipulative—exposes the misogyny and antisemitism embedded in the world of film preservation. Shrier’s gruesome death during the film’s climactic screening serves as poetic justice: a man who sought profit from horror becomes its literal victim.

Through him, the novel critiques how power structures feed on exploitation and how history’s monsters often hide behind respectable titles.

Molly Coolidge

Molly Coolidge, the homeless amputee whom Ellen befriends, functions as both mirror and moral compass. Her physical degradation reflects Ellen’s own emotional decay, and her brief refuge in Ellen’s apartment turns her into an unwilling participant in the unfolding nightmare.

Molly embodies human vulnerability in a story dominated by supernatural and ideological violence. Her disappearance after the massacre suggests that innocence cannot survive in a world corrupted by both fascism and forbidden art.

In Ellen’s final days, Molly’s memory lingers as a trace of empathy—perhaps the last vestige of humanity Ellen abandons.

Silas Graham

Silas Graham, the once-charismatic evangelist turned grotesque preacher, represents religious hypocrisy and the exploitation of fear. Invited to sanctify the screening of The Baroness, he becomes a parody of moral authority—denouncing sin while embodying gluttony and bigotry.

His sermon, steeped in antisemitism, transforms the theater into a cathedral of false virtue just before divine—or infernal—retribution descends. Graham’s death at the hands of the film’s manifested horrors symbolizes the collapse of sanctimony in the face of true evil.

He serves as a grotesque echo of Ellen’s own self-denial, reminding readers that repression and fanaticism spring from the same diseased root.

Janet Kramer

Janet Kramer, Ellen’s mother, embodies generational repression and denial. A product of postwar conservatism, she clings to appearances and patriarchal order, enforcing on her daughter the same moral suffocation that ruined her own life.

Her pressure on Ellen to marry Jesse and abandon her career illustrates the insidious violence of social conformity. When family secrets emerge—her mother’s Nazi collaboration—Janet’s façade of virtue collapses, revealing inherited guilt and self-hatred.

Her disownment of Ellen completes the cycle of betrayal that binds the Kramer lineage. Janet’s character underscores how personal and historical sins intertwine, passing like a curse through generations until they manifest in Ellen’s final descent.

Themes

Identity and Self-Loathing

Ellen Kramer’s journey in Black Flame revolves around the agonizing conflict between who she is and who she has been forced to become. Her repression of desire, particularly her attraction to women, mirrors the broader societal hostility toward difference.

The novel treats identity not as a static construct but as something fractured by shame, fear, and historical trauma. Ellen’s relationships with Jesse and Freddie expose how her self-loathing manifests in destructive intimacy—her sexual encounters are marked by numbness, disgust, and the absence of agency.

The book portrays her sexuality as a battleground where her personal and inherited guilt collide, especially within a Jewish identity that she both clings to and disavows under pressure from her conservative family. The supernatural infection that fuses her body with the cursed film becomes a physical manifestation of this internalized torment.

Through Ellen, the narrative explores how identity can be eroded by systems of power—patriarchy, fascism, religion—that demand conformity and purity. Her final transformation in the film’s infernal world is not redemption but a terrifying acceptance of the monstrous self that society has taught her to fear.

By embracing this darkness, Ellen rejects the moral binaries that have long imprisoned her, finding perverse liberation in what once marked her as unclean. The theme of identity and self-loathing ultimately captures the horror of existing as oneself in a world that insists on erasure.

Art, Corruption, and the Ethics of Representation

The restoration of The Baroness forms the narrative’s central moral question: can art that originates in evil still possess value? The novel situates this question within the shadow of fascism and exploitation, using film restoration as both metaphor and indictment.

Ellen’s work as a technician is presented as a ritual of resurrection—she is literally bringing the dead back to life. Yet as the film’s grotesque imagery begins to intrude upon her world, the act of restoration turns into contamination.

The question shifts from preservation to complicity: by reviving this creation, Ellen also revives its violence. The story condemns the aestheticization of atrocity, showing how art can perpetuate the very horrors it seeks to depict.

The elite figures funding the restoration—Shrier, Katz, and Graham—use the film’s notoriety for profit and propaganda, proving that art, once commodified, becomes another form of exploitation. The supernatural dimension of the cursed reel amplifies this idea, transforming film itself into a parasite that feeds on human suffering.

Black Flame uses the medium of cinema as a metaphor for history’s persistence: images of fascist cruelty never die; they return in new forms, infecting each generation that tries to sanitize them. The novel’s final massacre at the screening is the ultimate consequence of this moral corruption—art that refuses to stay dead demands a price paid in blood.

Trauma, Guilt, and the Inheritance of Violence

Throughout Black Flame, the boundaries between personal and collective trauma collapse, revealing the persistence of historical violence in contemporary life. Ellen’s psychic and physical deterioration parallels the resurgence of the horrors embedded in the cursed film, suggesting that trauma is not confined to the past but lives within the body.

The novel anchors this in her Jewish ancestry, particularly through the revelation of her grandmother’s collaboration with the Nazis. The guilt of survival becomes hereditary, shaping Ellen’s relationship to herself and her community.

Her haunting visions of Holocaust victims and spectral figures illustrate how the past refuses burial, demanding acknowledgment through pain. The theme of inherited guilt also extends to gendered violence—Ellen’s repeated sexual violations echo the historical subjugation of women under patriarchal and fascist systems.

Her father’s self-immolation and her own eventual participation in the film’s final blood ritual show that trauma, when unaddressed, becomes cyclical destruction. The “Black Flame” symbolizes this endless transmission of suffering: once lit, it burns through generations, consuming both oppressors and victims.

Gretchen Felker-Martin’s portrayal of trauma thus transcends individual psychology, casting it as an infection that seeps through art, history, and the body itself. The novel insists that there is no clean separation between the atrocities of the past and the violence of the present—only an ongoing struggle to survive their convergence.