Black in Blues Summary, Characters and Themes

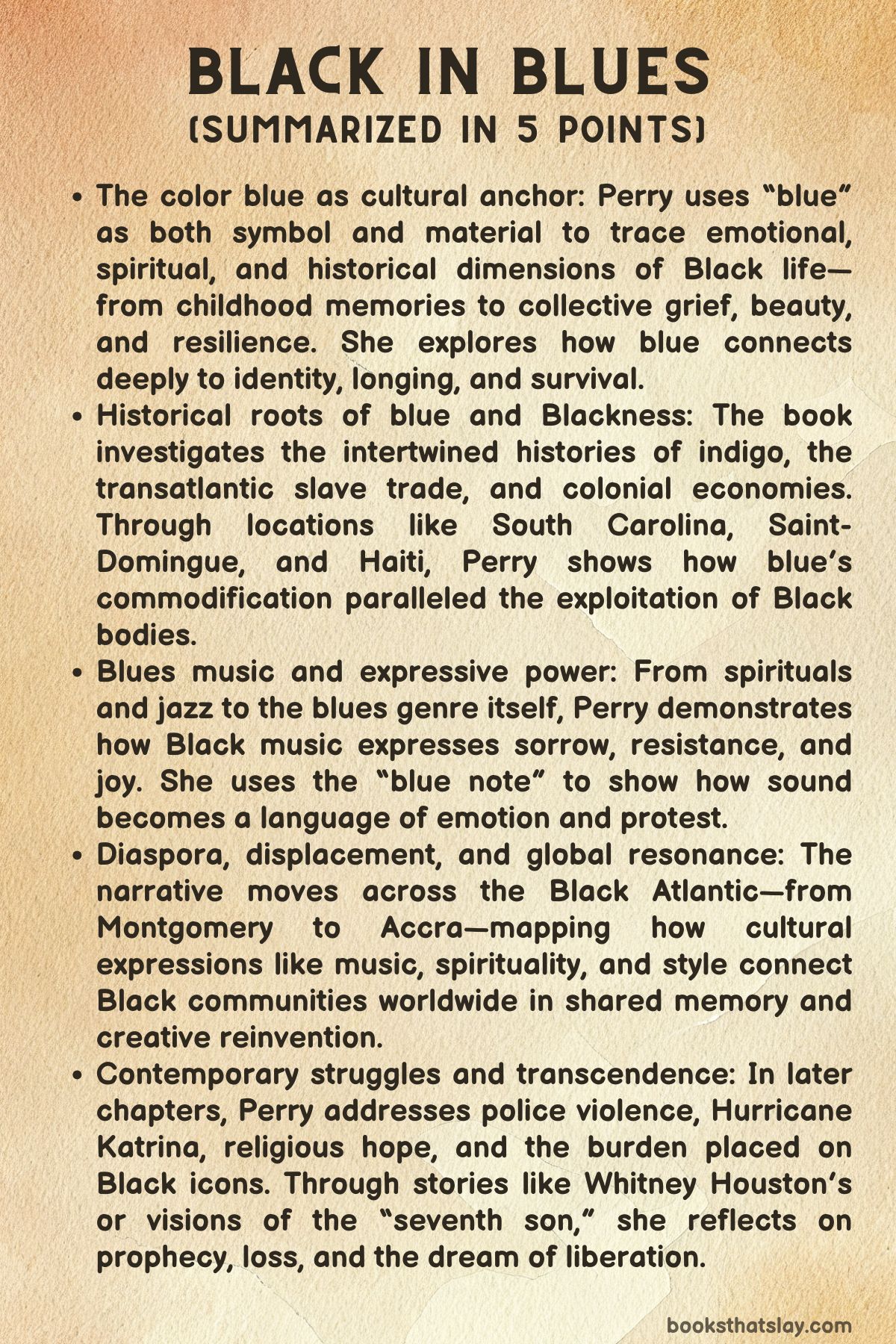

Black in Blues by Imani Perry is a sweeping, lyrical, and deeply researched meditation on the color blue as it courses through the arteries of Black history, identity, and expressive culture. More than a visual theme, blue becomes a method—an epistemology—for understanding Black life in all its contradiction, sorrow, creativity, and endurance.

Through historical narrative, personal memory, cultural critique, folklore, musicology, and spiritual reflection, Perry traces blue from indigo fields to jazz clubs, from colonial conquest to resistance movements. The book reclaims the blues not simply as music but as a worldview, turning color into metaphor, symbol, and repository for the complexities of Black experience across continents and centuries.

Summary

Black in Blues opens with a tender recollection from Perry’s childhood: a glimpse of a luminous blue in her grandmother’s room becomes the genesis for a vast and intricate exploration of the color blue. That color is not merely aesthetic; it is mnemonic, emotional, and political.

From that moment of domestic awe, the book radiates outward, uncovering how blue saturates Black life—in objects, stories, bodies, rituals, and songs.

The chapter “Our Blue Interior” sets the emotional tone for the book. Blue is shown as deeply embedded in the everyday lives of Black people, whether through the melancholy tones of blues music, the vibrant hues of indigo, or the aesthetics of adornment and spiritual practice.

Perry draws a direct connection between indigo—the plant harvested by enslaved Africans—and the cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic importance of blue in Black communities. Indigo was both a source of wealth for colonizers and of profound suffering for the enslaved.

Yet even in bondage, Black people found ways to transform the color into beauty, protection, and identity.

This spiritual and symbolic importance of blue is explored through African cosmologies, specifically in the kingdoms of Dahomey and Kongo, and through the cultural retention that survived enslavement in the Americas. Blue-painted porches, beads buried with ancestors, bottle trees, and Voudou altars dressed in blue—all of these testify to the resilience and continuity of African diasporic traditions.

Perry revisits the slave ship True Blue, where captives rebelled, and evokes revolutionary figures like Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Toya, who carried blue’s spiritual power into battle. For Perry, blue is elemental—it is a language of mourning and survival, a signifier of both trauma and transcendence.

Folklore and symbolism thread through the narrative. Blue jays, believed in southern folklore to consort with the devil on Fridays, are reimagined by Perry as subversive creatures, witness-bearers and truth-tellers.

Other animals like the blue tail fly and the Blue Boar racehorse serve as metaphors for cunning and resistance. Even dangerous myths, like the one surrounding “blue gums” as signs of poison, are unpacked to reveal both racist pathology and internal forms of empowerment and humor within Black communities.

The body and its shades are not spared from this scrutiny. Perry explores how blue-black skin, often stigmatized in a white supremacist world, came to be a site of both alienation and cultural pride.

Literary figures from Chesnutt to Morrison give these bodies symbolic potency—conjurers, seers, and moral anchors in narratives that otherwise flatten Black life.

The spiritual dimensions of blue extend into hoodoo and conjure traditions. Here, blue water, blue candles, and blue-stone are not merely decorative—they are sacred tools of protection, healing, and retaliation.

High John the Conqueror root and other blue-tinted remedies reveal a tradition rich in both pharmacological knowledge and symbolic resistance. Blue is invoked in ritual and prayer, inscribed in floors, and embedded in the very fabric of daily life—particularly in the art of quilting, which becomes another medium through which survival, beauty, and cultural memory are preserved.

Music is a central channel through which blue expresses its many meanings. The “blue note,” a musical concept in blues and jazz, becomes emblematic of emotional truth and artistic resistance.

Perry captures the bodily rhythms of Black performance—the breaths between notes, the sway of piano players, the communal hum of gospel—as forms of testimony and transcendence. These sonic traditions are not marginal; they are foundational, offering a grammar for enduring structural oppression with improvisation, grace, and power.

The material world also carries blue’s imprint. Ceramics, especially the work of Thomas Commeraw, a free Black potter in early America, illustrate how blue was not only an aesthetic but also an assertion of dignity and craftsmanship.

Perry contrasts Commeraw’s works with Wedgwood’s abolitionist cameos—blue jasperware that paradoxically critiqued slavery while being part of a system that profited from it. These objects, no matter their contradictions, preserve cultural memory.

In “Lonely Blue,” Perry explores diasporic narratives of individuals who bore their blues across oceans. Billy Blue in Australia and Daniel Blue in California are figures of solitude and courage, navigating foreign and often hostile spaces.

Their stories remind us that Black history is not confined to one geography but sprawls across empires and oceans, connecting struggles for freedom in unexpected places.

The chapter “Blue-Eyed Negroes” takes a hard look at racial ambiguity, colorism, and the cultural mythology surrounding blue eyes in Black bodies. W.E. B. Du Bois’s lament for his blue-eyed son becomes a point of departure for broader reflections on how racial boundaries are policed, traversed, and mourned. Blue eyes in Black communities have been read as both tragic and redemptive, evidence of violence and of grace.

Perry also examines the brutal ironies of empire and modernity in “Blue Flag, Gold Star. ” The Congo Free State’s pale blue flag with its gold star becomes a chilling emblem of colonial violence masquerading as enlightenment.

Through archival narratives, Perry revisits the grotesque abuses under King Leopold’s rule, linking blue to both illusion and revelation. The same color that adorned uniforms and flags marked the sites of massacre and mutilation.

And yet, through blues music—through the voices of Ma Rainey, Nina Simone, Louis Armstrong—the color is reclaimed. Songs like “What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue” become quiet declarations of dignity amid devastation.

In “The Boys in Blue,” Perry shifts the focus to modern civil rights struggles and the continued resonance of blue in political and artistic life. The beating of Miles Davis by police while promoting Kind of Blue stands as a symbolic moment.

Here, blue uniforms are no longer mythic—they are tools of state violence. But resistance is ongoing.

Denim overalls, associated with the working poor, become uniforms for activists. Bobby Blue Bland’s voice becomes a balm and a battle cry.

From Amiri Baraka’s Blues People to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, blue remains a central lens for interpreting Black suffering, creativity, and hope.

The book closes by returning to its central thesis: blue is not simply a color, not just an aesthetic or emotional motif. It is a system of knowledge and survival, a record of grief and brilliance, a language developed under siege and passed through generations.

Through story, song, prayer, object, and body, Perry argues that Blackness is inseparable from the blues—not just musically, but philosophically. It names what hurts, but it also offers the means to live on, to remember, and to create.

Black in Blues becomes not just a cultural history but a spiritual archive, a manifesto for recognizing and honoring the intricacies of Black life.

Key People

Imani Perry

At the heart of Black in Blues, particularly in the essay “Our Blue Interior,” is the intimate and philosophical presence of Imani Perry herself. As both narrator and subject, Perry constructs her identity in layers—historian, cultural theorist, storyteller, and granddaughter—braiding the personal and political with grace and gravitas.

Her character is defined by a deep emotional sensitivity that allows her to engage not only with cultural artifacts and historical events, but also with their affective and spiritual consequences. She interprets blue as a color of pain and transcendence, embodying her own journey through the legacy of Blackness in the Americas and across the diaspora.

Perry’s inner life, especially her childhood memories, spiritual reflections, and scholarly rigor, are never separated; instead, they coalesce into a living portrait of a woman whose intellect is inseparable from her embodied experience. She is neither didactic nor detached.

Her authority as a narrator comes from her vulnerability, her ability to weave personal inheritance with collective memory, and her insistence on honoring contradiction, nuance, and improvisation as epistemologies. Perry emerges not just as a chronicler of the blues, but as a bearer of its spirit—resilient, aching, curious, and defiantly alive.

Asi (from “Blue Goes Down”)

Asi, the mythic figure in the Liberian folktale retold in “Our Blue Interior,” is portrayed as a tragic and deeply symbolic character whose story echoes across generations. Her hunger for the sky—so intense that she devours it until her child is lost—represents the fatal intersection of longing, grief, and cosmic yearning.

Asi is not simply a mother but a vessel for allegory. Her narrative embodies a yearning so vast that it crosses spiritual and moral boundaries, a metaphor for diasporic dislocation and the consequences of insatiable desire in a world shaped by colonial extraction.

Asi is a figure of maternal loss, of celestial hunger, and ultimately, of sorrow that shapes the cultural memory. Her story reverberates with the themes Perry investigates throughout the book—how beauty and destruction coexist, how ancestral myth is never just a story but a coded legacy of trauma and resilience.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Toya

Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his mentor Toya are presented not simply as historical revolutionaries, but as spiritual and cultural figures infused with blue’s metaphysical charge. Dessalines, leader of the Haitian Revolution, is more than a general; he becomes a symbol of transformative Black agency, an embodiment of vengeance sanctified by justice.

His role in the narrative is dual—military and mythic—constructed not just through historical events but through his spiritual alliances with Vodou deities, most of whom are coded in blue. Toya, his mentor and spiritual guide, becomes a maternal force of empowerment, emphasizing that leadership is nurtured by ancestral wisdom, not individual will.

Together, they articulate the revolutionary possibility born of a deep interior world—a “blue” world rooted in history, sacrifice, and metaphysical faith.

The Blue Jay

Though not a human character, the blue jay functions as an animistic presence in Perry’s narrative, symbolic of layered, often contradictory Black identity. Folklore paints the bird as mischievous and garrulous, possibly in league with the devil—yet Perry subverts this reading by casting the blue jay as a subversive truth-teller.

In her view, it becomes a “Black familiar,” capable of saying what could not be said, of carrying the voices of the oppressed when it was too dangerous for them to speak directly. The blue jay is thus imbued with spiritual intelligence and resistance.

Its character mirrors that of Perry’s own voice—restless, analytical, and defiantly unafraid to uncover uncomfortable truths.

High John the Conqueror and Brother Blue

High John the Conqueror and Brother Blue are folk and cultural icons woven into the broader narrative of spiritual resistance and artistic survival. High John, a mythical figure in African American folklore, symbolizes unbreakable spirit and cunning.

Perry invokes him as part of the Hoodoo tradition, tying him to the color blue and the magical, medicinal practices of survival. He represents the spirit that cannot be captured, that always finds a way to turn oppression into power.

Brother Blue, in contrast, is a real historical figure—Hugh Hill, a street storyteller who turned blue into a living aesthetic of resistance. His transformation from Ivy League scholar to griot of the people encapsulates the ethos of blue that Perry explores throughout the book.

Both figures live in the borderlands between myth and history, art and life, reminding readers that identity is as much performed as inherited, as much improvised as codified.

Erzulie and Agwe

The Vodou deities Erzulie and Agwe emerge as divine figures tied explicitly to the color blue and to the spiritual infrastructure of Black resistance. Erzulie, associated with love, beauty, and feminine power, and Agwe, connected to the sea and navigation, are not simply symbols but active presences in the cosmology of freedom and survival.

Perry invokes them to suggest that blue is not just historical or cultural—it is sacred. These deities inhabit the liminal space between resistance and ritual, marking the sacred continuity that exists even in enslaved or colonized spaces.

Their presence signals a deep metaphysical structure beneath the visible acts of rebellion, affirming that Black liberation has always had a spiritual as well as political dimension.

In Black in Blues, characters—whether historical, mythical, folkloric, or personal—do not stand alone. They form a chorus of voices that affirm blue as a lived truth: mournful, magical, and enduring.

Each one, from Asi to Perry herself, carries within them a shade of this truth, reminding the reader that Black identity is never singular, never still, and always resonant.

Themes

Blue as Cultural Memory and Kinship

Blue operates as a repository for cultural memory, embedding layers of familial, spiritual, and communal knowledge within its spectrum. From the vivid memory of a sky-colored ceiling tile in a grandmother’s room to the indigo-stained hands of enslaved ancestors, blue is not simply a color but a coded language of remembrance.

In Black in Blues, it becomes a mnemonic device, a way to hold close what was stolen or threatened with erasure. It contains the rhythms of blues music, the notes of gospel, the shimmer of beads buried in sacred rituals, and the wash of porches painted to ward off evil.

Through such symbols, blue serves as a bridge between generations—both a comfort and a resistance. Family stories, aesthetic practices like quilting or beadwork, and rituals tied to Vodou or Hoodoo demonstrate how blue is used to maintain coherence and survival under systemic pressure.

It connects a global diaspora through shared artistic forms and traditions, resisting the fragmentation imposed by slavery, colonization, and racial capitalism. It also functions as an archive not written in official histories but stored in fabrics, oral tales, spiritual altars, and body memory.

Thus, blue becomes the palette through which Black people narrate themselves back into existence—not through the language of conquest, but of care, continuity, and cultural fidelity.

The Politics of the Body and Racial Myth

Blue as it appears on or within the body becomes a site for both mythic projection and real-world harm. In Black in Blues, the physical body—whether through the trope of “blue gums,” blue-black skin, or blue eyes—becomes a contested territory on which identity, fear, and resistance play out.

Myths about poisonous bites from blue-gummed individuals or the spiritual potency of the darkest-skinned figures have long served both to pathologize and to mystify Blackness. These myths were not just external projections by white supremacy; they were often internalized, debated, or reinterpreted within Black communities themselves.

The result is a double-edged inheritance: danger and power, marginalization and reverence. Such representations are never neutral.

They reveal how racial ideologies permeate even intimate understandings of kin, of self, of what is considered beautiful or monstrous. Additionally, blue eyes in Black children, a mark of ancestry’s violence and the fraught legacy of rape and racial mixing, evoke sympathy and estrangement in equal measure.

These bodily manifestations of blue reflect deeper anxieties about belonging, purity, and legitimacy within and outside the community. Yet, through stories, jokes, literature, and art, these same features are reclaimed as signs of spiritual potency, defiance, and self-definition.

Resistance, Survival, and Improvisation

Throughout Black in Blues, blue is consistently linked to acts of survival that are at once mundane and extraordinary. Whether it is enslaved people painting their doorframes with blue to ward off spirits, jazz musicians bending notes beyond Western norms, or griots like Brother Blue transforming the street into a sanctuary of storytelling, blue becomes an improvisational ethic.

It is not merely resistance in the conventional political sense, but a deeper, almost instinctive strategy for living under pressure without breaking. Blue becomes survival with style—with sound, with touch, with color, and with memory.

It is survival that insists not only on enduring but on shaping the world through wit, movement, and aesthetic mastery. Artists, musicians, and even revolutionaries enact blue as a mode of agency—evident in the denim-clad activists of the Civil Rights Movement, in the spiritual invocations of Haitian Vodou, and in the melodic lamentations of Billie Holiday or Curtis Mayfield.

Blue teaches that resistance does not always look like confrontation; sometimes, it looks like grace under pressure, or a bottle tree glittering in a southern yard, quietly catching the light—and the ghosts.

State Violence and the Blue Uniform

The recurring image of the police uniform—the “boys in blue”—recasts blue as a symbol of terror rather than peace. This motif in Black in Blues begins with the violent beating of Miles Davis and extends outward to CIA-led assassinations, state surveillance, and police brutality in both domestic and international arenas.

Blue here is not healing, but bruising. It is the color of sanctioned violence, of systemic force wrapped in the language of order.

Yet the essay does not stop at exposure; it also examines how this blue is countered. The Nation of Islam’s protests, the legal battles of figures like Daniel Blue, and the cultural defiance of artists like Amiri Baraka offer alternative visions.

Even garments like denim—once known as “negro cloth”—are reappropriated into symbols of political identity and protest. These juxtapositions of coercion and creativity—of blue as both bruiser and banner—highlight the ongoing dialectic between oppression and reclamation.

The state may mark its dominance in blue, but so do the people who resist its reach through fashion, voice, and ritual.

Diasporic Loneliness and Transnational Blackness

Blue in Black in Blues is also the color of solitude and wandering. Figures like Billy Blue in Australia or Daniel Blue in California exemplify the diasporic Black experience—one marked by mobility, marginalization, and persistence.

These men and women, cast across oceans and centuries, inhabit a liminal space: neither fully of the place they find themselves in, nor entirely disconnected from the places they’ve left behind. The loneliness of diaspora is not simply geographic; it is ontological.

It’s the dissonance of being at home in a culture yet alien to its dominant narrative. Yet, even in this loneliness, blue offers connection.

It offers a rhythm, a history, a shared memory carried in the body and in art. It becomes a signal across time and space—a way of recognizing oneself in the voice of a blues singer or the indigo of a ritual garment.

Transnational Blackness, then, is not homogenized but harmonized, and blue is the shared frequency.

Commodification and Fetishization of Blackness

In tracing the history of blue through objects like Wedgwood pottery, the essay confronts the uneasy entanglement of beauty and exploitation. Blue becomes a fetish object—used in fine ceramics and high fashion, yet always shadowed by the bodies whose labor made it possible.

The same color used to decorate abolitionist cameos was also used to brand sugar bowls benefiting from slavery. The paradox is clear: Blackness has been aestheticized, marketed, consumed, and sanitized in white supremacist culture, even as its lived experience was denied and brutalized.

This tension plays out in marketing terms like “nigger blue” and beverages designed to exoticize Black culture. Yet artists like Sonya Clark and Vanessa German re-imbue these objects with memory and resistance, reframing commodified blue as a site of testimony.

Through these works, the author critiques not only historical systems of racial capitalism but the ongoing appetite for Black culture stripped of its political urgency. Blue, in this context, becomes a battleground between art and appropriation, presence and erasure.

Blue as Spiritual Practice and Emotional Truth

Across its pages, Black in Blues treats blue not only as pigment but as praxis. It is a spiritual code that governs mourning rituals, conjuring traditions, musical improvisation, and political imagination.

Blue is a form of knowing—an epistemology shaped by the blues scale, by bottle trees that glisten with souls, by water spirits like Erzulie, and by the hands that rub High John the Conqueror root into the cracks of floors and lives. It embodies emotional truths too complex for rational systems to contain.

The “blue note” becomes a metaphor for this kind of wisdom—uncapturable by traditional notation, but deeply felt and profoundly communicative. Blue teaches not just how to survive, but how to feel fully while doing so.

In its devotion to stories, rituals, and signs, Black in Blues affirms blue as a sacred grammar—one that names suffering but also insists on its sublimation into beauty, testimony, and love.