Bonfire Night Summary, Characters and Themes | Anna Bliss

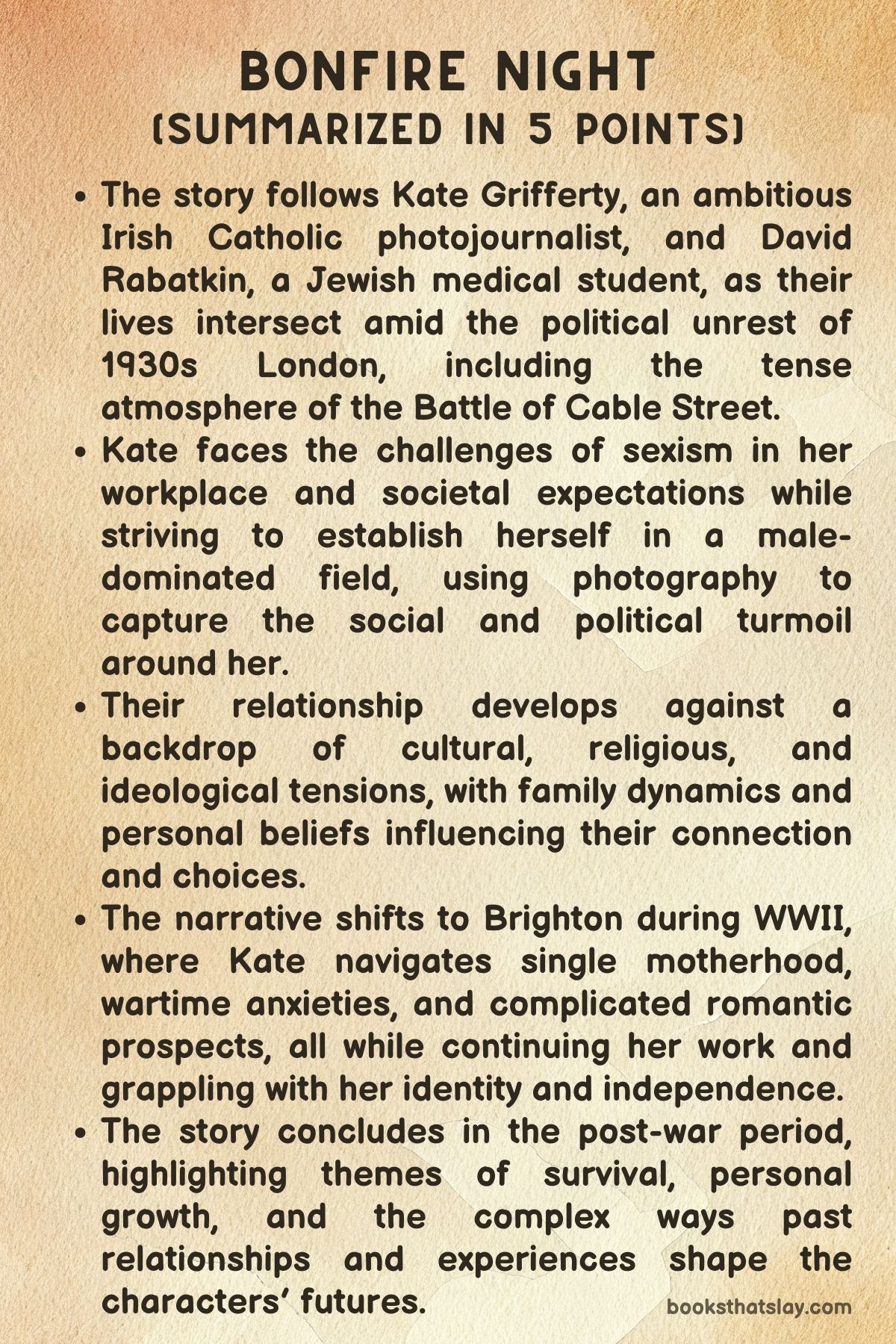

Bonfire Night by Anna Bliss is a historical novel set against the backdrop of 1930s and 1940s England, capturing the tumultuous years before, during, and after World War II.

The story follows Kate Grifferty, an ambitious Irish Catholic photojournalist, and David Rabatkin, a Jewish medical student, whose lives and love intertwine in a world roiling with political unrest, prejudice, and societal change. Through vivid settings from London’s East End to the seaside town of Brighton, Bliss explores themes of identity, resistance, motherhood, and the enduring human need for connection.

Summary

Bonfire Night opens in London in 1936, a city teetering on the edge of upheaval.

Kate Grifferty is determined to make her mark as a photojournalist in a newsroom dominated by men who doubt her abilities.

Her camera becomes both her shield and weapon as she documents the growing tension between fascists and anti-fascists in the East End.

During the infamous Battle of Cable Street, Kate captures powerful images of Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts clashing with locals, risking her safety to tell the story.

However, professional setbacks and the entrenched sexism at Central Press continually threaten to stifle her voice.

It’s amid this chaos that Kate meets David Rabatkin, a sensitive and principled Jewish medical student.

Their encounter is fraught with the complexities of London’s charged political climate, as well as the personal baggage each carries—Kate’s Catholic heritage and difficult family background, and David’s deep roots in his Jewish community.

Despite these differences, an undeniable chemistry grows between them, fueled by their shared longing for meaning and belonging.

Kate’s home life is marked by distance and loss.

Her father, emotionally absent since her mother’s death in childbirth, offers little warmth or support.

Her elder sister, Orla, is stern and practical, struggling in her own way to protect the family’s fragile bonds.

Kate’s sense of isolation is palpable, and her determination to succeed in journalism is as much about proving herself to others as it is about escaping the shadows of her upbringing.

David, meanwhile, is torn between family obligations and personal desires.

His brother Simon, a firebrand political activist, and Simon’s partner Myriam, a passionate Communist, push David to question the world around him—and, by extension, his relationship with Kate, who is more pragmatic than political.

These tensions play out not only in family debates but in the subtle, daily negotiations of living as a minority in a city increasingly hostile to outsiders.

As Kate and David’s romance deepens, so do the risks.

They navigate moments of joy—a night dancing at the Tottenham Royal, quiet conversations that bridge their differences—but they are never free from the scrutiny of friends and family, nor the looming threat of war.

Each must confront uncomfortable truths: Kate about her own ambition and the compromises she’s willing to make; David about the cost of blending loyalty to heritage with love that transcends boundaries.

With the outbreak of World War II, the narrative shifts to Brighton, where Kate seeks refuge with her daughter Margaret and her sister Orla.

The move is both an escape and a fresh start.

Kate tries to settle into the routines of wartime Britain, juggling single motherhood with work and a tentative engagement to Clifton Prouty, an RAF officer who offers her stability.

But Kate’s sense of restlessness persists—her heart never fully at ease, her ambitions as fierce as ever.

Motherhood in wartime brings its own perils and revelations.

A near-tragedy during an air raid shakes Kate to her core, driving home the fragility of life and the stakes of every decision she makes.

Despite societal pressures to conform—to remarry, to settle down—Kate insists on forging her own path, both for herself and her daughter.

Through anonymous but significant photographic contributions to the war effort, she reclaims her sense of agency and pride.

In the novel’s closing stages, Kate has built a new life in postwar Richmond, surrounded by family and friends.

The scars of loss and separation linger, but so does the hope that comes from survival and the promise of new beginnings.

The story’s ultimate resolution, and whether Kate and David find their way back to each other, remains undisclosed—inviting readers to reflect on love’s endurance and the possibilities that lie ahead after the storm.

Characters

Kate Grifferty

Kate is the central figure of Bonfire Night, portrayed as a fiercely ambitious and independent Irish Catholic woman navigating pre-war and wartime England. Her drive to become a successful photojournalist puts her in direct conflict with the gender norms of her era.

From the start, she confronts workplace sexism and dismissiveness, particularly from her boss, Mr. Scargill, who both acknowledges her talent and belittles her because of her gender. Kate’s Irish Catholic background also sets her apart in a predominantly Protestant and often anti-Irish society, compounding her outsider status.

Emotionally, Kate is shaped by a cold and distant family life—her mother’s death in childbirth, her father’s emotional unavailability, and a distant relationship with her older sister Orla. These early losses and challenges fuel her independence and make her emotionally guarded, but they also leave her longing for connection and acceptance.

As the story progresses into wartime Brighton, Kate is further tested by single motherhood and the chaos of the Blitz. Her relationship with her daughter Margaret becomes a source of vulnerability and strength, pushing her to choose authenticity and self-determination over security, even when it means breaking off her engagement with Clifton Prouty.

By the epilogue, Kate’s journey comes full circle as she finds professional success and a stable home life, suggesting a quiet resilience and capacity for reinvention.

David Rabatkin

David is a sensitive and principled Jewish medical student whose relationship with Kate drives much of the novel’s emotional core. Deeply connected to his Jewish heritage and family, David is nonetheless drawn to Kate’s independence and unconventionality.

His internal conflict stems from balancing family expectations—especially religious and cultural loyalty—with his personal desires and love for Kate. David’s family represents both a source of strength and pressure, as his brother Simon’s radicalism and the broader anti-Semitic climate of 1930s London make David’s choices fraught with meaning.

During the war, David’s sense of duty leads him to become a military doctor, further complicating his relationship with Kate as the world around them is reshaped by violence and loss. Although he and Kate share moments of profound connection, David ultimately chooses to move forward with his life, finding love and family elsewhere.

His presence in the epilogue—returning as a friend with his new family—demonstrates a capacity for forgiveness, growth, and enduring respect between himself and Kate.

Orla Grifferty

Orla, Kate’s older sister, plays a more understated but crucial role as a steady, pragmatic counterpoint to Kate’s restlessness. Orla’s initial emotional distance is partly a result of the same family trauma that shaped Kate, but unlike her sister, she seeks stability and security, often through traditional roles.

When Kate and Margaret move to Brighton, Orla becomes a supportive presence, providing both practical help and emotional grounding. As the household’s anchor, she enables Kate to pursue her work and independence, especially during wartime upheaval.

By the epilogue, Orla’s role as a co-parent and companion in Richmond underscores the importance of chosen family and mutual support in the aftermath of war and personal loss.

Simon Rabatkin and Myriam

Simon, David’s brother, embodies the political radicalism and ideological ferment of 1930s London. His passionate commitment to communism and social justice often puts him at odds with Kate, whose initial apolitical stance he openly challenges.

Simon’s girlfriend, Myriam, shares his convictions and acts as both confidante and provocateur, pushing Kate to question her beliefs and the limits of her neutrality as a journalist. The pair represent the era’s youthful idealism and the sense of urgent moral responsibility, providing a political backdrop that complicates and enriches Kate’s and David’s personal choices.

Clifton Prouty

Clifton is an RAF officer and, for a time, Kate’s fiancé in Brighton. He represents the promise of security and conventional respectability, contrasting sharply with the unresolved passion and complexity of Kate’s relationship with David.

Clifton is decent, reliable, and caring toward both Kate and Margaret, but ultimately, his traditional expectations and Kate’s need for independence prove incompatible. Clifton’s significance lies in what he offers Kate—a glimpse of safety in a chaotic world—and what she ultimately rejects, highlighting her evolution toward self-reliance.

Margaret Grifferty

Margaret, Kate’s daughter, is both a source of vulnerability and hope. Her near-fatal experience during a bombing in Brighton becomes a turning point for Kate, intensifying her protective instincts and reaffirming her commitment to motherhood over social convention.

Margaret’s presence in the story catalyzes Kate’s major decisions, from withdrawing her from the evacuation scheme to refusing a safe but loveless future with Clifton. By the end, Margaret embodies both the trauma and resilience of wartime children, and her relationship with Kate represents a hard-won, intergenerational healing.

Arthur Keyes

Appearing in the epilogue, Arthur Keyes is a writer and Kate’s new romantic partner. His presence signals Kate’s newfound stability and contentment after years of turmoil.

Arthur is not given the same narrative weight as David or Clifton, but his role is symbolic—representing a future grounded in mutual respect and companionship, rather than conflict or compromise.

Mr. Scargill

Mr. Scargill is Kate’s boss at Central Press in London and stands as a representative of the institutional sexism and condescension faced by ambitious women in the 1930s. His grudging recognition of Kate’s talent is always laced with dismissiveness, serving as an obstacle Kate must continually overcome.

While not a major character in terms of page time, Scargill’s attitudes reflect the larger societal challenges Kate faces in her quest for professional recognition.

Themes

Collision of Personal Identity and the Demands of History

Throughout Bonfire Night, the narrative intricately examines how individuals struggle to maintain a sense of personal identity in the face of overwhelming historical forces. The protagonists—Kate Grifferty and David Rabatkin—are continually shaped and reshaped by the seismic political and social events of their era, most notably the rise of fascism in 1930s London and the devastation of World War II.

The Battle of Cable Street, a watershed moment in British anti-fascism, serves as a crucible where private ambitions and fears are tested against collective ideologies and public conflict. Kate’s journey as an Irish Catholic woman in a male-dominated field and David’s experiences as a Jewish medical student illuminate the ways in which heritage, faith, and personal values are constantly challenged by external pressures.

Their attempts to forge genuine connections and self-understanding are rendered more difficult by the ever-shifting expectations of their families, communities, and the tumultuous times in which they live. The novel suggests that identity is neither fixed nor wholly self-determined, but is forged in the crucible of historical necessity and the demands of the moment.

Transmission of Trauma and the Search for Emotional Inheritance

Anna Bliss crafts a subtle but powerful meditation on the ways trauma—both personal and collective—is inherited and transformed across generations. Kate’s emotional coldness, rooted in the loss of her mother at birth and her father’s distant manner, becomes a shaping force in her adult relationships and her approach to motherhood.

The war years intensify this inheritance: the bombing of Brighton, the omnipresent threat to her daughter Margaret, and the constant presence of loss reawaken old wounds and shape new ones. Similarly, David’s family history, marked by Jewish persecution and the burden of religious expectation, informs his actions and choices in ways he struggles to fully articulate.

As the narrative moves into its postwar epilogue, the characters’ attempts to reconcile the demands of the past with the hope of renewal underscore the persistence of emotional legacy—one that can be both a source of pain and a foundation for new beginnings.

The novel ultimately interrogates whether true healing is possible, or if each generation must reinterpret the scars left by those before them.

Female Autonomy Within Patriarchal and Wartime Structures

Bonfire Night resists simplistic readings of female empowerment, instead portraying Kate’s pursuit of autonomy as fraught with paradox and compromise. As a woman in pre- and postwar Britain, Kate must navigate institutional sexism, as seen in her experiences at Central Press, and the subtle coercions of domesticity and motherhood.

The war simultaneously expands and constricts her horizons: while it opens new professional opportunities (e.g., war photography, editorial roles), it also imposes fresh restrictions in the form of state propaganda work, gendered expectations around childcare, and the moral policing of women’s romantic lives. Kate’s refusal to accept marriage to Clifton Prouty as a solution to her social or economic vulnerability highlights the incomplete and sometimes pyrrhic nature of her victories.

Even as she attains professional recognition and personal contentment in the epilogue, the narrative remains attuned to the unfinished struggle for women’s freedom—a struggle shaped as much by internalized constraints as by external obstacles.

Faith, Secularism, and the Politics of Belonging in a Fractured Society

Religious identity in Bonfire Night is never merely a matter of private belief; it is intimately tied to questions of belonging, exclusion, and social justice. David’s Jewishness, experienced both as a wellspring of family solidarity and as a source of vulnerability, stands in tension with Kate’s Catholic background and her more secular, sometimes skeptical worldview.

The novel resists sentimentalizing religion, instead portraying it as a site of both solace and conflict—an axis around which issues of authenticity, assimilation, and resistance turn. The pressures of antisemitism, political radicalism (as embodied by Simon and Myriam), and the lure of apolitical retreat are all explored as competing responses to a fractured society.

The result is a nuanced portrayal of how faith, doubt, and ideological commitment shape not only personal destinies but also the larger political alignments of the era.

The Limits of Romantic Idealism in the Shadow of Social Upheaval and War

Central to the novel is a sustained critique of the idea that romantic love can serve as a refuge from or answer to the world’s injustices. The relationship between Kate and David is defined as much by external pressures—religious, cultural, political—as by genuine affection and attraction.

Their inability to fully reconcile these differences, and Kate’s eventual choice not to rekindle their love even when the opportunity arises, underscores the novel’s skepticism toward romantic idealism. Instead, love is depicted as contingent, fragile, and sometimes necessarily subordinated to the demands of survival, ethical responsibility, and self-realization.

The epilogue’s tableau of blended families, new partnerships, and enduring—if muted—connections serves as a bittersweet acknowledgment of both loss and endurance: love persists, but not always in the forms we might wish or expect.

Unseen Labour of Survival and the Quiet Heroism of Everyday Life

Finally, Bonfire Night pays tribute to the countless, often invisible acts of endurance, adaptation, and care that constitute survival in times of crisis. From Kate’s decision to withdraw her daughter from the evacuation scheme, to Orla’s steadfast presence, to David’s service as a wartime doctor, the novel foregrounds the daily, unglamorous work required to hold families, communities, and selves together.

This theme is especially resonant in the aftermath of war, where the heroism of ordinary life—editing a newspaper, tending to a garden, raising a child—emerges as the foundation of postwar reconstruction. The novel insists on the dignity and significance of these quiet labors, positioning them as the true counterweight to the destructive forces of history.