Boys Who Hunt Summary, Characters and Themes

Boys Who Hunt by Clarissa Wild is a dark, provocative romance that explores the brutal intersections of survival, obsession, and power. Set in the elitist and dangerous world of Spine Ridge University, the novel follows Ivy Clark, a young woman burdened by poverty, motherhood, and secrets, who dares to defy the rich and violent Skull and Serpent Society.

As she navigates betrayal, manipulation, and forbidden desire, Ivy becomes entangled with three men—Silas, Heath, and Max—whose control over her teeters between protection and domination. With raw depictions of trauma and twisted love, the book portrays one woman’s fight for agency in a world that seeks to consume her.

Summary

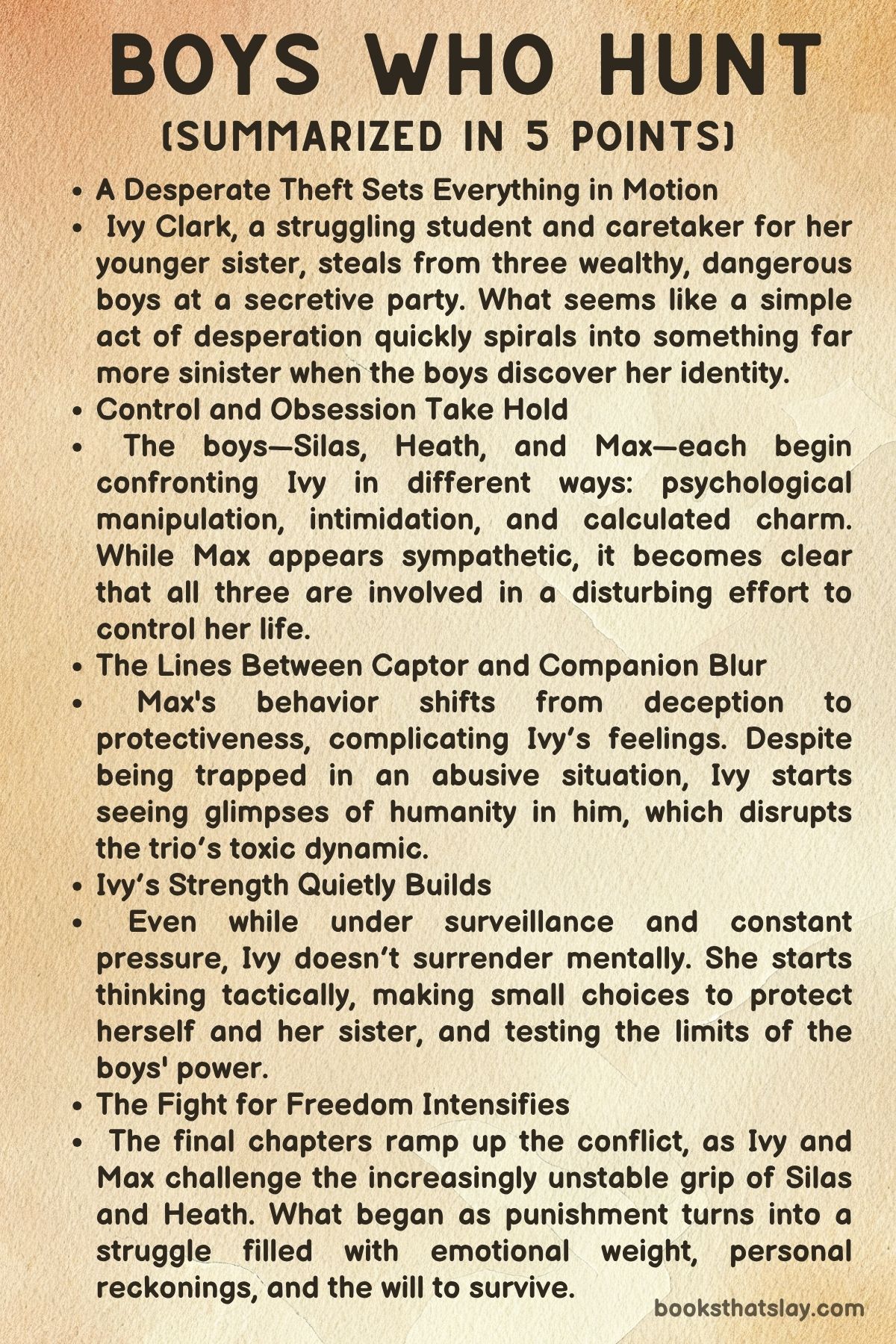

Ivy Clark is a university student by day and a thief by night, trying desperately to support her younger sister, Cora, in the corrupt and privileged world of Spine Ridge University. Her life is one of calculated risk—balancing lectures, shifts at nightclubs, and heists targeting the rich boys of the Skull and Serpent Society.

Everything changes after a particularly bold robbery where Ivy breaks into the dorm rooms of Silas, Heath, and Max, stealing money, valuables, and a peculiar red plastic flower. That flower, seemingly insignificant, becomes the trigger for a chain reaction of obsession and pursuit.

Silas, the most dangerous of the trio, is especially affected, descending into a near-psychotic fixation on discovering the thief’s identity and punishing them.

The theft does not go unnoticed. When the boys find a hearing aid dropped by Ivy, they connect the dots.

Silas confronts her in a bathroom, where the encounter teeters between menace and seduction, establishing the threatening undercurrent of their relationship. Silas’s need for control and Ivy’s refusal to submit creates a violent tension that only intensifies as he becomes obsessed with breaking her.

Meanwhile, Heath and Max plot a subtler form of manipulation. They use Max’s crush on Ivy to bait her into confessing, feigning kindness while hiding their ulterior motives.

Ivy, though constantly on edge, continues her ruse. Her past is riddled with hardship—an ailing father, lost dreams, and a child she must protect at any cost.

Her life is not one of luxury or freedom, but of calculated desperation. When she loses her job after a tense confrontation with Heath at the club, Ivy retreats to a rundown shack on a nearby mountain, hoping to stay off the radar while keeping Cora safe with a neighbor.

Hunger and fear plague her, but Ivy remains focused on survival.

Max approaches Ivy, attempting to charm her and gather evidence against her. He buys her a meal and offers comfort, but Ivy, untrusting and driven by need, steals from him once more.

This theft, however, was anticipated. The group uses it as an excuse to initiate a brutal manhunt.

Ivy is cornered in the forest by Silas and Heath, who take disturbing pleasure in the pursuit and her eventual surrender. Faced with no way out, Ivy offers herself, trading her body for safety.

This surrender, born from exhaustion and maternal instinct, marks a turning point in the story’s intensity.

Max, though shaken by what he witnesses, cannot deny his own role in the betrayal. His guilt and feelings for Ivy begin to deepen.

When Ivy is later attacked by masked assailants, she is saved by Silas, who violently annihilates her attackers. The rescue, however, is not an act of compassion but a violent display of ownership.

Silas claims Ivy as his, bringing her to safety while asserting control. Heath and Max soon join them, and the situation becomes more complicated when they all discover Ivy’s secret—Cora is not her sister, but her daughter.

This revelation changes the dynamic between Ivy and the three men. Cora’s presence humanizes Ivy in their eyes.

Silas, despite his earlier cruelty, pledges to protect both mother and child, claiming them as part of his world. Max and Heath follow suit, revealing layers of protectiveness and jealousy.

They move Ivy and Cora into the Skull and Serpent Society estate, where the men attempt to create a twisted version of domestic life. Silas cooks for them, trying to show affection through clumsy gestures.

Cora softens their rough edges, charming even Silas, who struggles with her innocence and how it conflicts with his brutality.

However, tensions rise between the men. Heath and Max vie for Ivy’s attention, their rivalry igniting old wounds and unresolved feelings.

Ivy, too, is caught in the chaos, unsure of her feelings and the cost of their protection. She is torn between gratitude and fear, affection and trauma.

The narrative intensifies when Ivy and the men reenact the original “hunt,” but this time as a symbolic ritual. Ivy willingly participates, allowing herself to be caught, chased, and bound.

Her consent is no longer a form of surrender but a reclamation of power within the warped dynamic she now shares with Silas, Heath, and Max.

Their sexual encounters escalate, marked by sadomasochistic play that walks a razor’s edge between love and violence. Silas carves his name into Ivy’s skin, a symbolic act of possession that Ivy does not resist.

Max provides emotional tenderness, while Heath grapples with vulnerability and control. These men, once tormentors, become something more complex: partners in Ivy’s survival and, paradoxically, her sense of belonging.

The final sections reveal a softening of the brutal world they inhabit. Ivy is given a new room, clothing, and a dedicated space for Cora, signaling her permanent place in their twisted family.

Silas, Heath, and Max begin to confront their pasts. In particular, Heath reconnects with his sister, Cecelia, and learns she left voluntarily for boarding school, not under duress as he believed.

This moment of closure allows him to discard the pills he used to numb himself, embracing his chaotic emotions and newfound purpose.

The novel ends with the group accepting one another for who they are—damaged, dangerous, but deeply connected. Ivy, once hunted, now stands as the center of a brutal but fiercely loyal family.

Her pain has not disappeared, but she has transformed it into strength, drawing power from her ability to endure, protect, and even love within the darkest corners of their shared existence. Boys Who Hunt closes on a note of strange contentment, where the monstrous has become familiar, and Ivy’s survival has reshaped the meaning of home, love, and loyalty.

Characters

Ivy Clark

Ivy Clark is the fiercely resilient heart of Boys Who Hunt, a young woman forged by hardship, desperation, and the weight of her responsibilities. From the outset, she is portrayed as a resourceful survivor, juggling the roles of university student, devoted guardian to her daughter Cora, and a nighttime thief targeting the privileged elite of Spine Ridge University.

Her character is grounded in duality—she is both the predator and the prey, hardened yet vulnerable, fiercely independent yet increasingly enmeshed with the very forces that threaten her autonomy. Ivy’s thievery is not born of malice but necessity; every action she takes is driven by the need to protect and provide for Cora.

Her love for her daughter is a constant refrain that elevates her from being a morally ambiguous character to a deeply empathetic one. Despite enduring manipulation, coercion, and physical danger, Ivy remains unyielding in spirit.

Her intelligence, quick thinking, and emotional depth allow her to navigate the labyrinthine games of power and control played by the Skull and Serpent Society. As the narrative progresses, Ivy transforms—not by shedding her pain but by embracing her own darkness.

Her ultimate decision to join, and even revel in, the brutal passion of her captors is less a surrender and more an act of reclamation. She does not merely survive the chaos; she becomes an integral part of it, finding strength and even a warped sense of love in the madness.

Silas

Silas is perhaps the most disturbing and complex figure in Boys Who Hunt, embodying both the monstrous antagonist and the obsessive lover archetype. From his first appearance, Silas is depicted as a sadist, a man who takes immense pleasure in cruelty, dominance, and fear.

His pursuit of Ivy is at first driven by vengeance and control, but it quickly mutates into a haunting obsession that blurs the line between possession and love. Silas’s emotional makeup is a volatile mix of psychopathy and vulnerability; he exerts control through violence and intimidation, yet is profoundly shaken when confronted with Ivy’s emotional depth and her daughter Cora’s innocence.

The moment he intervenes to save Ivy from masked attackers—and later when he prepares breakfast and awkwardly interacts with Cora—reveals his capacity for tenderness, albeit filtered through a deeply twisted lens. Silas’s act of carving his name into Ivy’s skin is a grotesque expression of love and ownership, marking a moment where dominance and devotion become indistinguishable.

His complexity lies in his ability to be terrifying yet strangely endearing, brutal yet capable of change. Silas is not redeemed in the traditional sense, but his emotional arc suggests an unlearning of pure violence in favor of a more complicated, if still dangerous, emotional intimacy.

Heath

Heath emerges as a deeply conflicted figure whose brutality masks a history of pain and confusion. Initially introduced as one of the orchestrators of Ivy’s torment, Heath is sadistic in his own right, participating in mind games, sexual domination, and manipulation.

Yet his character is more nuanced than mere villainy. Heath’s aggression seems to stem from unresolved emotional trauma, particularly surrounding his estranged relationship with his sister Cecelia.

His impulsive kiss with Max reveals hidden layers of sexual fluidity and internal turmoil, signaling a man at war with himself. Heath’s complicity in Ivy’s suffering is undeniable, but his character arc takes a notable turn when he chooses to stay and protect both Ivy and Cora.

His reunion with Cecelia is a pivotal moment that liberates him emotionally, culminating in the symbolic act of discarding his pills—an act of reclaiming his mental state and embracing emotional vulnerability. Though he begins as a tormentor, Heath gradually becomes a guardian figure, his love for Ivy and Cora shifting from possessive to protective.

His transformation is not sanitized but made all the more compelling by its messiness. In the chaos of their unorthodox relationship, Heath finds a version of himself he can finally accept.

Max

Max is the most emotionally accessible and seemingly gentle of the three men, serving as the emotional bridge between Ivy and the more extreme personalities of Silas and Heath. Initially used as bait to manipulate Ivy, Max’s genuine affection for her becomes apparent early on.

He provides her with food, kindness, and the illusion of safety, creating a false sense of trust that makes his eventual complicity in the plot all the more devastating. However, Max’s remorse and emotional turmoil distinguish him from the others.

He is the only one who consistently expresses empathy—not just through words, but through actions that reveal his inner conflict. Max’s love for Ivy deepens over time, evolving from infatuation into a more stable, though still complex, emotional bond.

He forms a paternal connection with Cora, participating in the domestic scenes at the Skull and Serpent estate with sincerity. Max’s voyeuristic tendencies and his participation in the more violent aspects of their sexual dynamic complicate his character, but he never loses sight of Ivy’s humanity.

He is the character most capable of change and emotional articulation, often acting as the conscience of the group. Max embodies the paradox of being both complicit in cruelty and capable of genuine love.

Cora

Though young and largely passive in the storyline, Cora is a symbolic and emotional anchor in Boys Who Hunt. Her presence humanizes Ivy and forces each of the men to confront aspects of themselves they typically suppress.

For Ivy, Cora represents innocence, responsibility, and the very reason for every sacrifice she makes. For Silas, Heath, and Max, Cora is a disarming presence that disrupts their violent instincts and awakens latent emotions.

Cora’s interactions with the trio offer moments of levity and tenderness in an otherwise brutal narrative. Her ability to charm even Silas, who is initially unsettled by her, signals a shift in the household dynamic.

Though she does not drive the plot actively, Cora’s role is essential to the emotional growth of every major character. She is the embodiment of hope, softness, and future—the very things Ivy fights to protect and the reasons the men are eventually compelled to change.

In sum, Boys Who Hunt presents a cast of deeply damaged, morally ambiguous characters whose transformations are forged in fire. Ivy, Silas, Heath, Max, and even young Cora are bound together by pain, love, and an unconventional reimagining of what family, loyalty, and healing can look like in a world steeped in darkness.

Themes

Power and Exploitation

Boys Who Hunt portrays a brutal world governed by hierarchical power dynamics, where physical dominance, wealth, and secrecy allow predators to operate with impunity. From the outset, the Skull and Serpent Society exemplifies an elite class shielded from accountability.

Ivy’s entanglement with Silas, Heath, and Max is not one of romantic choice but of systemic coercion—she is a woman surviving in a world designed to exploit her vulnerabilities. Each encounter, whether at a party, in a nightclub, or in the forest, becomes a battleground where power is not only exerted through threats and violence but also through manipulation, seduction, and psychological degradation.

Silas, in particular, embodies a disturbing portrait of control. His actions move beyond retribution and into obsessive ownership, using fear and dominance as tools to bend Ivy’s will.

Even seemingly tender acts, such as preparing breakfast or giving Ivy a room, are saturated with unspoken debts, reinforcing how deeply exploitation is embedded into every gesture. Ivy is not merely caught between three men; she is forced to navigate a web of control disguised as protection, desire masked as entitlement, and punishment cloaked in affection.

The novel does not glorify this power imbalance—it underscores how difficult it is to escape when the very systems meant to provide safety and structure have been corrupted into mechanisms of harm.

Survival and Desperation

Survival is the pulse that drives every choice Ivy makes. Her thievery, her calculated risks, and even her willingness to endure humiliation are not rooted in rebellion or thrill-seeking—they are born of desperation.

Ivy is responsible not just for herself but for Cora, a dependent whose safety hinges on Ivy’s ability to stay invisible, solvent, and alive. The narrative emphasizes how survival in a corrupt world often means making excruciating compromises, such as selling one’s body or trust, just to delay disaster.

Ivy’s constant hunger, her decision to sleep in an abandoned shack, her theft of a plastic flower from Silas—all are symbolic of a broader theme: how the poor and vulnerable must claw their way through a world rigged against them. What heightens the tragedy is Ivy’s intelligence and drive; she’s a university student with potential, but potential has no currency in a world that preys on weakness.

Even when she is offered protection by her tormentors, it comes at a cost: her autonomy. In Boys Who Hunt, survival is not just about outliving danger—it’s about the endurance of spirit when every exit from poverty or harm is booby-trapped with moral compromise, betrayal, or subjugation.

Trauma and Emotional Repression

The story intricately reveals how trauma shapes behavior, identity, and emotional capacity. Ivy is deeply scarred by past and present horrors—her father’s death, the burden of raising Cora, the fear of being discovered, and the relentless assault on her physical and emotional autonomy.

Yet her response is not overt vulnerability; it is tightly coiled resilience. She represses her emotions, masks her fear, and wields sarcasm or theft as shields.

This repression, however, is not a sign of strength but a survival mechanism. Each time Ivy cries—be it after a stolen moment of care or in the safety of her daughter’s embrace—the release is brief and quickly buried.

Her interactions with Max, who appears emotionally available, contrast sharply with the cruelty of Silas and the volatility of Heath, yet even Max becomes a pawn in the emotional chessboard of manipulation. The men, too, are emotionally fractured.

Heath’s misplaced guilt over his sister and dependence on pills indicate unresolved internal chaos. Silas’s inability to separate affection from violence speaks to a broken psyche that equates domination with intimacy.

Emotional trauma in the novel is not merely past-tense damage; it is an ongoing force, pressing down on every character, guiding their worst decisions, and making genuine healing nearly impossible without reckoning with the emotional repression they each carry.

Consent and Control

Boys Who Hunt presents a deeply uncomfortable exploration of consent, challenging the reader to confront how coercion can masquerade as desire when power is unevenly distributed. Ivy’s choices are repeatedly stripped away by the dominance of the Skull and Serpent Society members, particularly in sexual and psychological contexts.

Though the text occasionally depicts moments of Ivy’s arousal or willingness, these are juxtaposed against a backdrop of fear, desperation, and calculated survival. The question of true consent becomes murky when submission is the only perceived route to safety or protection.

The “hunt” scenes, the sadomasochistic encounters, and even Ivy’s decision to offer her body are not framed as liberated expressions of sexuality—they are symptomatic of a woman negotiating the least painful way to stay alive. The book’s most disturbing moments—Silas carving his name into her skin, Ivy using sex as a bargaining chip—expose how easily dominance erodes agency.

What makes the narrative even more unsettling is the way it reflects real-world dynamics, where saying “yes” can be a survival strategy rather than a desire. This theme pushes the boundaries of romance fiction, forcing a confrontation with how trauma, fear, and social imbalance strip away the dignity of choice, leaving characters like Ivy with consent that is technical but not authentic.

Identity, Shame, and Redemption

At its core, the novel is also a story about hidden identities and the shame that clings to them. Ivy hides not just from society but from the people closest to her.

She conceals her poverty, her child, her crimes, and her trauma, not out of pride but out of a deeply internalized shame that tells her she must pretend to be normal to survive. This shame is mirrored in the men as well—Heath’s guilt over his sister’s departure, Silas’s violent coping mechanisms, Max’s passive complicity.

Yet the path to redemption is not a clean one. It is violent, chaotic, and wrapped in morally gray decisions.

Redemption, when it comes, does not offer absolution but a redefinition of identity. Heath stops his medication not because he’s cured, but because he’s ready to face the darkness without numbing it.

Silas provides protection not out of generosity, but as a gesture of obsession reconfigured as care. Ivy, too, does not emerge as a triumphant heroine in the traditional sense—she survives, but her acceptance of the trio is fraught, steeped in pain and compromise.

Redemption in Boys Who Hunt is not about becoming good; it is about being fully seen in one’s darkest form and still being chosen, loved, and claimed. It’s messy, brutal, and emotionally raw, but in the world the book constructs, it’s the only form of healing possible.