Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future Summary and Analysis

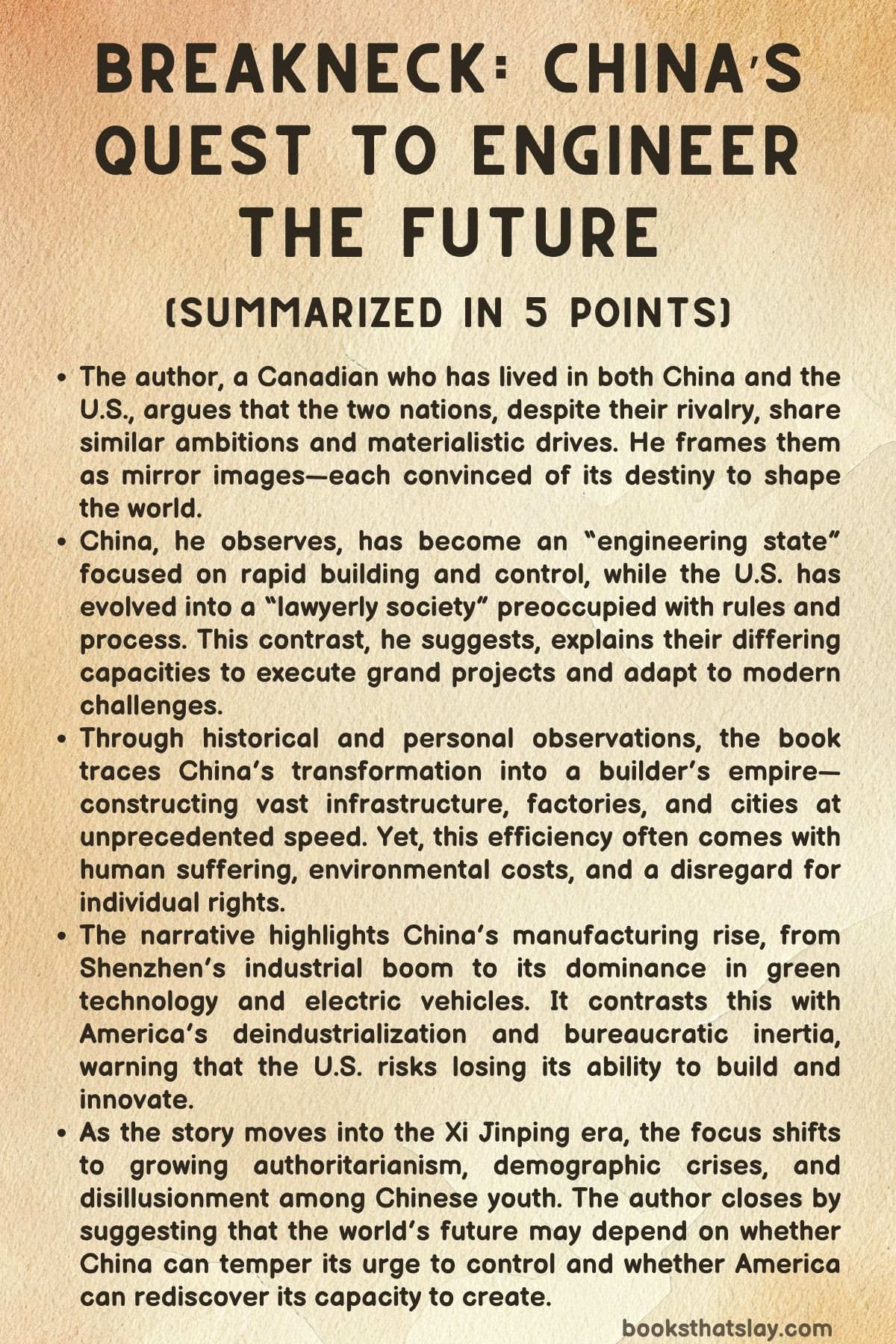

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future by Dan Wang explores how modern China has become the world’s most ambitious experiment in engineering—of infrastructure, economy, and even society itself. Drawing on his experience living between China, the U.S. , and Canada, Wang contrasts two great powers: China, driven by the logic of engineers, and America, governed by lawyers.

He presents a nuanced portrait of how China’s obsession with building—bridges, factories, cities, and control systems—has transformed it into a superpower, yet also trapped it in cycles of waste, repression, and overreach. This book examines how China’s “engineering state” shapes not only its own destiny but the world’s future balance of power.

Summary

Dan Wang’s Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future examines the forces driving China’s modern rise and the contrasting stagnation of the United States. As a Canadian who has lived in both nations, Wang provides a dual perspective, observing how China’s relentless drive to build and America’s fixation on law and regulation have reshaped the global order.

His narrative unfolds as both a historical chronicle and a philosophical reflection on technology, power, and national character.

The book opens with Wang’s assertion that China and the United States, despite being adversaries, are more similar than they appear. Both nations are animated by ambition, material success, and a belief in their world-shaping destiny.

Yet their methods diverge: China is an “engineering state,” seeking progress through physical creation and control, while America is a “lawyerly society,” bogged down in procedure and litigation. These cultural instincts define their contrasting trajectories—China’s meteoric rise versus America’s slow decay in infrastructure and productivity.

Wang traces China’s transformation from an impoverished agrarian nation to an industrial and technological power. He recalls the leadership of engineers since Deng Xiaoping, who prioritized physical development—roads, railways, and factories—as a means to national rejuvenation.

Under Xi Jinping, this technocratic impulse has hardened into authoritarian efficiency. China has built dazzling highways, high-speed rail, and megacities at record speed, often through sheer command and disregard for human cost.

America, once the archetypal builder of highways and spacecraft, has become paralyzed by lawsuits and regulatory delays, unable to complete even basic infrastructure like California’s high-speed rail.

The book contrasts these two governing classes—China’s engineers and America’s lawyers. Wang recounts how China’s policymakers, many trained in engineering, approach problems through construction, while American leaders, often lawyers, approach them through negotiation and paperwork.

The results are visible: China’s breathtaking transformation versus America’s aging bridges and stagnant cities. However, he cautions that China’s speed often breeds recklessness.

The same system that builds record-breaking bridges also enables environmental destruction, debt, and waste. He illustrates this through the story of Guizhou province, where a frenzy of bridge and highway building has produced world-class infrastructure but left behind poverty and depopulation.

From the macroeconomic perspective, Wang contrasts China’s supply-driven model with America’s demand-driven one. China’s growth has relied on high savings, investment, and manufacturing exports, while America’s has rested on consumption and regulation.

Each system has reached its limits: China builds too much and consumes too little; America consumes too much and builds too little. For both, the challenge is cultural—China must learn restraint and empowerment of individuals, while the U.S. must rediscover the will to construct.

The rise of Shenzhen exemplifies China’s industrial miracle. Once a fishing village, it became the center of global manufacturing, home to Foxconn and the factories that produce the iPhone.

Through relentless imitation and experimentation, China developed deep “process knowledge”—the practical expertise that allows it to make and refine nearly anything. This technical base fueled industries from drones to electric vehicles.

By contrast, America’s offshoring of manufacturing hollowed out its industrial skill base, leaving corporations dependent on foreign production and eroding their practical engineering culture.

Wang distinguishes between three kinds of technology: tools, instructions, and process knowledge. China’s strength lies in the third—the ability to produce, modify, and perfect through experience.

America’s decline in manufacturing has weakened its ability to innovate materially, turning it into a “software nation” dependent on ideas but detached from production. China’s leaders, recognizing this, now seek self-sufficiency and “completionism”—ensuring that every part of the industrial chain, from basic materials to advanced chips, remains within the country.

This vision of total industrial sovereignty, Wang argues, reflects a lingering fear of foreign humiliation and dependence.

The book also explores China’s social engineering projects, most notably the one-child policy. Originating from scientific and military elites, the policy treated population like a controllable variable.

For decades, officials enforced it through coercion, forced abortions, and sterilizations. Though it succeeded in slowing population growth, it left deep scars—gender imbalance, aging demographics, and a declining workforce.

Even after its end in 2015, the legacy of state control over reproduction persists, now inverted into pronatalist campaigns urging women to marry and have multiple children. Under Xi, women’s autonomy has shrunk further; propaganda celebrates motherhood and obedience while suppressing feminist movements.

Wang portrays this as the ultimate expression of the engineering state—attempting to plan human life itself.

His account of China’s pandemic years forms one of the book’s most striking sections. During the Zero-Covid era, the same engineering logic of control was applied to public health.

The initial triumph of containing the virus gave way to excess—mass lockdowns, surveillance, and deprivation. In Shanghai, residents went hungry as supply chains collapsed and drones commanded citizens to “suppress your soul’s yearning for freedom.” The system’s efficiency turned cruel, showing that the same machinery that builds cities can imprison them. The “white paper protests” of 2022, when citizens held blank sheets to symbolize censorship, became a fleeting eruption of dissent before the state abruptly ended the policy.

The pandemic period accelerated a national reckoning. Many Chinese, especially youth, lost faith in the system and sought to “rùn”—to escape abroad.

Chiang Mai in Thailand became a haven for these exiles, who found freedom in small bookstores and expatriate communities. Their departure mirrored a larger exodus of capital and talent, as the Chinese state tightened ideological and regulatory control.

Wang describes the decline of China’s tech giants—Alibaba, Tencent, Didi—crushed under Xi’s campaign against the “disorderly expansion of capital. ” The goal was to reassert the supremacy of the state, redirecting innovation from consumer apps to “hard tech” industries vital to national power.

Under Xi, the engineering state entered a new phase: fortress-building. Focus shifted from growth to security, from openness to self-reliance.

The leadership, dominated by aerospace and defense engineers, prioritized semiconductors, energy, and weapons over culture and liberalization. The result was an economy more insulated and militarized, yet technologically formidable.

China’s control over the supply chains of batteries, solar panels, and electric vehicles gave it unprecedented leverage in global industry. Its cultural influence, however, stagnated.

Strict censorship stifled creativity, leaving China far behind neighbors like Japan or South Korea in global soft power.

In the final chapters, Wang reflects on his family’s journey from China to Canada. His parents left behind poverty and fear for freedom and predictability, though materially they gained little.

Their story encapsulates the trade-off at the heart of modern civilization—freedom versus control, process versus productivity. For Wang, China’s engineering state represents mastery without mercy, while America’s lawyerly system embodies liberty without capacity.

Both are incomplete. He calls for a synthesis: a society that builds like China but governs with America’s pluralism.

Ultimately, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future is not just about China’s speed but about humanity’s struggle to balance power and freedom. Wang’s account reveals that the future will hinge on whether China can humanize its engineering impulse and whether America can rediscover how to build.

The contest between them is not only geopolitical but philosophical—a test of what kind of civilization can construct a future worth living in.

Key People

Dan Wang, the Narrator

A Canadian observer who has lived deeply in both the United States and China, the narrator is the book’s moral compass and synthesizer. He blends memoir, reportage, and analysis to map the psychological engines of two superpowers he considers “twin” in ambition and destiny.

His professional vantage as a technology analyst sharpens his eye for factories, infrastructure, and policy; his years on the ground in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai attune him to the volatility of everyday life under tightening control. He is neither cheerleader nor scold.

Instead, he becomes a patient cartographer of paradox—able to admire the audacity of high-speed rail while recording the trauma of lockdowns; to lament American procedural paralysis while defending its pluralism; to trace how process knowledge, not slogans, actually moves the world.

Xi Jinping

Xi is rendered as the architect and steward of the contemporary engineering state: a leader who prioritizes control, completion, and national security over market spontaneity or cultural experimentation. In this telling, his governance reorients China from exuberant consumer internet ventures toward “hard tech,” pushes for self-reliance across strategic supply chains, and expands surveillance infrastructures that outlived the pandemic.

He is the force that ends one kind of social engineering—the one-child regime—only to inaugurate another through pronatalism, shrinking divorce access, and intensified monitoring. The portrait is not psychological but structural: Xi is the consolidator who trades openness for order, dynamism in culture for dominance in industry.

Deng Xiaoping

Deng appears as the godfather of pragmatic modernization whose reforms seeded both China’s industrial ascendance and the technocratic temperament that later hardened under Xi. He sanctioned experiments like Shenzhen’s special economic zone and elevated engineers within party ranks, embedding the conviction that building—bridges, plants, cities—was both policy and proof of legitimacy.

The narrative suggests that Deng’s legacy is double-edged: it made possible a civilization of makers while normalizing a managerial impulse that treats society as an object to be optimized.

Song Jian

A missile scientist turned population theorist, Song personifies technocracy at its most hubristic. His pseudo-scientific modeling of an “optimal” population helped rationalize the one-child policy, demonstrating how engineering prestige can drift into social planning with catastrophic human consequences.

He is less a fully drawn personality than an emblem of method misapplied: the transformation of mathematical neatness into bureaucratic cruelty.

Li Zaiyong

Li functions as a case study in the perverse incentives of construction-led politics. His rise on the back of spectacular but ill-conceived projects—like a “ski resort” in a tropical province—captures how metrics of visible achievement can eclipse economic sense.

When fortunes reverse, his disgrace mirrors the boom-and-bust theatrics of cadre careers tethered to concrete rather than to durable welfare.

Yiju

A young software developer who joined the white-paper protests and fled when the police came looking, Yiju embodies the post-Zero-Covid exodus and the slang of “rùn. ” He is not a dissident in grand pose but a practical idealist, drawn to the breathable spaces of Chiang Mai, banned books, and fragile communities of Chinese exiles.

Through him, the story captures a generational mood—technically skilled, politically cautious yet newly outspoken, and convinced that dignity requires distance from the omnipresent state.

Themes

The Engineering State and the Lawyerly Society

In Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang explores two fundamentally different modes of governance through the metaphors of engineering and law. China, as an “engineering state,” seeks progress through construction, scale, and control, while the United States, as a “lawyerly society,” has grown preoccupied with process, legality, and restraint.

The analysis of this contrast reveals how deeply political culture shapes a nation’s ability to act. In China, engineers dominate policymaking, seeing every social and economic issue as a problem to be solved through technical design and infrastructure.

This mindset has produced astounding physical transformation—railways stretching across mountains, megacities rising from farmland, and bridges linking isolated provinces. Yet it also breeds an unrelenting faith in control and efficiency, leaving little space for dissent, debate, or ethical reflection.

Human welfare often becomes secondary to the achievement of tangible results, as seen in the enforcement of the one-child policy or the zero-Covid lockdowns.

America, by contrast, has drifted toward paralysis. Its political and economic elite—largely trained as lawyers—emphasize procedure, compliance, and litigation.

The rule of law, once a foundation for innovation and fairness, has evolved into a web of constraints that slow decision-making and discourage ambition. The decay of infrastructure and the endless delays in public projects exemplify a society that measures virtue by caution rather than accomplishment.

Wang’s portrait is not one of simple opposition but of mutual deficiency. China’s system builds relentlessly but crushes the individual, while America’s system protects rights yet cannot deliver collective progress.

The comparison lays bare a moral and structural question: whether governance should prioritize action or deliberation, and whether either approach can sustain a prosperous, humane civilization.

Material Progress and Human Cost

The story of China’s rise, as Wang presents it, is a paradox of triumph and exhaustion. The nation’s transformation from impoverished agrarian society to global industrial leader embodies an extraordinary drive for material progress.

Cities, highways, and factories symbolize the victory of human will over nature and poverty. Yet behind this visible success lies a quieter tragedy—the diminishment of individual agency and well-being in the name of collective advancement.

The engineering state treats people as components in a grand machine, measured by output rather than dignity. The author recounts how the construction of bridges and rail lines mirrors the construction of social policies: both executed with precision and ruthlessness.

The one-child policy stands as the most chilling expression of this mentality. Using demographic models derived from missile science, the state applied engineering logic to human life, enforcing population control with violence and surveillance.

The policy’s human consequences—infanticide, forced abortions, and a gender imbalance of millions—expose the cost of governing society as a technical system. Decades later, the government’s attempt to reverse the demographic collapse by coercing births reveals the same impulse to control outcomes through administrative design.

Wang’s narrative suggests that China’s success is inseparable from its suffering; the grandeur of its projects cannot be divorced from the lives constrained or broken in their pursuit. Material progress, when achieved through coercion, becomes both a source of pride and a wound that refuses to heal.

Technology, Industry, and National Identity

China’s industrial ascent is not merely economic—it is existential. In Breakneck, Wang portrays manufacturing as the foundation of China’s modern identity, the arena where national pride and power are forged.

Shenzhen’s transformation from fishing village to megacity represents the country’s faith in production as destiny. Through partnerships with Western corporations like Apple, Chinese engineers and workers accumulated process knowledge—the deep, tacit expertise that cannot be codified in blueprints.

This mastery turned China into the “workshop of the world,” capable of building everything from smartphones to solar panels.

Wang argues that China’s determination to maintain a full spectrum of manufacturing, even in unprofitable sectors, reflects a deep-seated anxiety about vulnerability. The memory of “technological humiliation” at the hands of colonial powers fuels a doctrine of “completionism,” the belief that only a self-reliant industrial base can secure sovereignty.

In contrast, America’s outsourcing of production hollowed out its technical culture and eroded its sense of purpose. The United States excels in software and finance but has lost touch with the material realities of making.

China’s factories, though harsh and exploitative, sustain a living ecosystem of experimentation and learning. Wang thus frames industrial power as a moral as well as strategic question: which society truly honors skill, and which has abandoned it?

For China, manufacturing is not just an economic engine but a source of national meaning—a reaffirmation that creation, even when mechanized, is the path to dignity and endurance.

Control, Surveillance, and the Architecture of Obedience

A central theme in Wang’s account is the evolution of China’s surveillance state into a permanent architecture of obedience. The zero-Covid years exposed how far the government’s desire for control could extend into the private sphere.

Every movement, purchase, and social interaction became measurable through health codes, apps, and neighborhood committees. The infrastructure of pandemic management—QR codes, drones, checkpoints—transformed into the skeleton of a total surveillance system.

Wang’s portrayal of Shanghai’s lockdown captures the suffocating intimacy of authoritarian control: hunger, isolation, and the psychological toll of being watched and confined in one’s own home.

Yet the system’s power lies not only in coercion but in normalization. Citizens came to expect constant monitoring as a condition of safety and order.

The transition from emergency response to everyday governance blurred the line between protection and domination. After the pandemic, the same bureaucratic machinery was redirected toward tracking women’s fertility, showing how seamlessly technological control can migrate across domains of life.

The author implies that China’s “engineering state” has perfected a form of digital authoritarianism that fuses efficiency with obedience. It is a society where public order is absolute but private freedom is vanishing, where even dissent must express itself in silence, as in the “white paper protests.

” Wang’s account reveals that control in China is not merely political—it is infrastructural, embedded in the very systems that sustain daily life.

Migration, Disillusionment, and the Search for Freedom

The emergence of “rùn”—the slang for escape—captures the emotional collapse of a generation raised on the promise of progress. Wang’s depiction of young Chinese emigrating to places like Chiang Mai reflects a collective disillusionment with the moral direction of the nation.

These “runners” are not rebels in the traditional sense; they are engineers, artists, and professionals seeking oxygen in a system that has grown too suffocating. Their flight signifies the erosion of faith in the social contract that once traded obedience for opportunity.

The exodus of talent and capital after Xi Jinping’s crackdowns on tech firms further underscores a society turning inward, retreating into isolation even as it builds outward.

Wang’s narrative connects this disillusionment to a deeper spiritual fatigue. After decades of relentless construction, the Chinese people confront the limits of ambition without liberty.

The engineering state can produce prosperity, but not purpose. For those who leave, the act of running becomes an assertion of agency, a quiet rebellion against total design.

Yet emigration is also an admission of defeat—a recognition that the dream of a humane modernity within China may be fading. Wang’s reflections on his own departure frame this theme with poignancy: admiration for the country’s energy coexists with exhaustion from its rigidity.

The search for freedom, whether through exile or introspection, becomes the final movement of the book—a reminder that progress without personal autonomy ultimately leads to escape, not belonging.

The Dual Decline of China and America

The final argument of Breakneck is that China and the United States, despite their rivalry, are mirror images in decline. China’s overbuilding and repression reflect the excesses of control, while America’s stagnation and bureaucracy reveal the paralysis of freedom.

Both nations, Wang suggests, are trapped by their own systems—one unable to stop building, the other unable to start. The comparison exposes the fragility of modern civilization: technical mastery and moral vitality no longer align.

The United States has lost its confidence in collective action, content with procedures that safeguard individual rights but obstruct shared purpose. China, conversely, has achieved collective might by sacrificing the individual.

Wang envisions a future in which survival depends on synthesis. America must rediscover its capacity to build—its engineering courage—while China must learn to temper its power with humanity.

The competition between the two is not only geopolitical but civilizational, testing whether progress can coexist with freedom. His concluding meditation on his parents’ immigrant journey reinforces this theme: prosperity and liberty rarely coincide, and every society must choose what kind of poverty it prefers—the material poverty of freedom or the spiritual poverty of control.

In framing both nations as “developing countries” of different kinds, Wang invites readers to see that the quest to engineer the future is not just China’s—it is the defining challenge of the modern world.