Burn Bright Summary, Characters and Themes

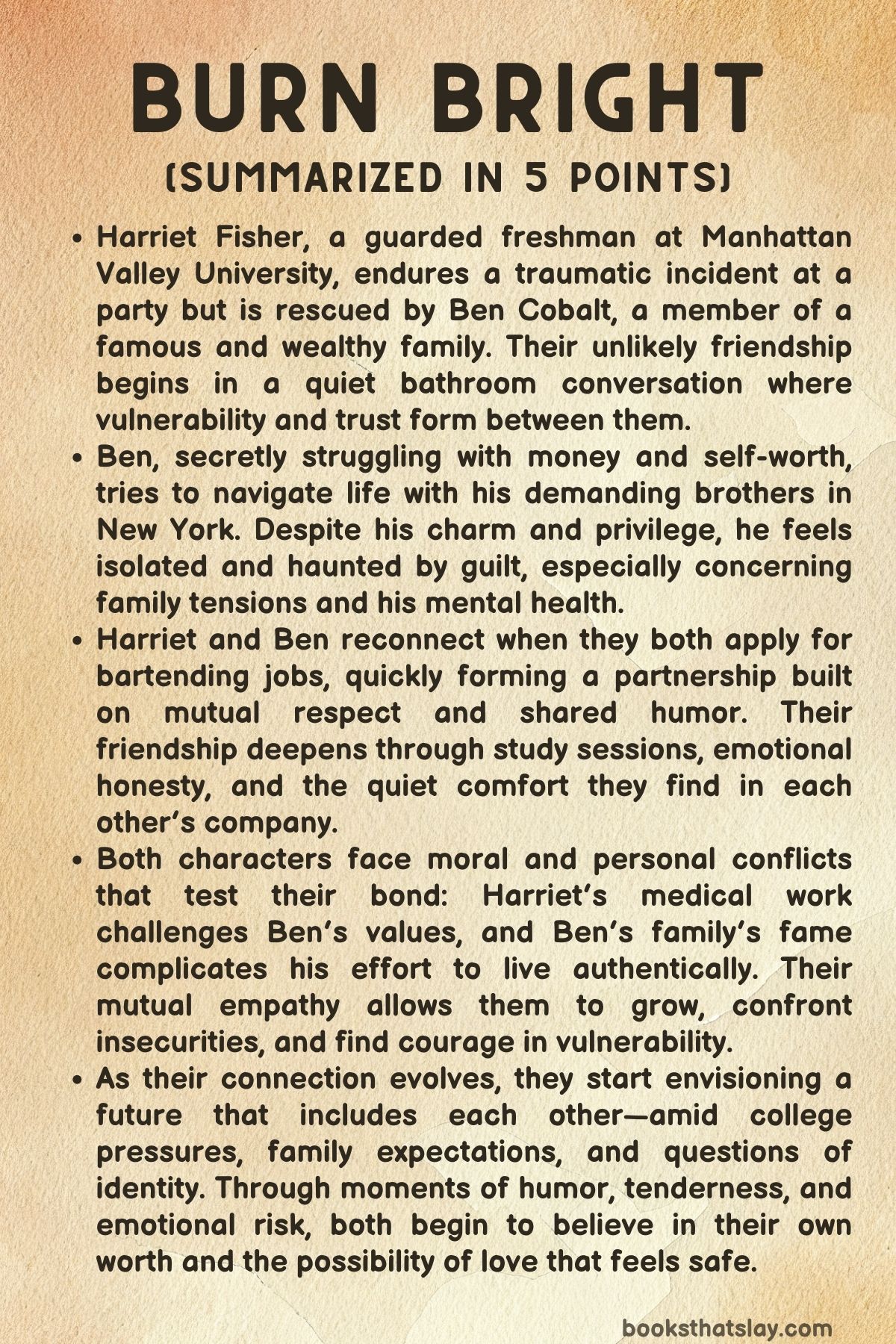

Burn Bright by Krista and Becca Ritchie explores the fragile, messy intersections of friendship, love, and identity through the eyes of two complex individuals—Ben Cobalt and Harriet Fisher. Set in the buzzing world of Manhattan Valley University and the wider orbit of the renowned Cobalt family, the novel balances the glamour of privilege with the rawness of personal struggle.

It follows two people wrestling with isolation, family expectations, and moral dilemmas as they form a connection that is both healing and destabilizing. Through intimate conversations, quiet acts of care, and shared vulnerabilities, the story unfolds as an exploration of self-worth, trust, and the courage it takes to be seen.

Summary

Harriet Fisher begins her freshman year at Manhattan Valley University determined to break out of her isolation. Against her instincts, she forces herself to attend a fraternity party, hoping to connect with others.

The night quickly turns humiliating when two row-team members harass her, mocking her weight and physically dragging her toward a pool. Just before she’s thrown in, someone intervenes—Ben Cobalt, a strikingly familiar name tied to one of America’s most famous families.

He helps her to safety, checks if she’s hurt, and when she flees to a bathroom in panic, he patiently waits until she lets him in.

Inside, they sit on the floor and talk. Despite her guarded nature, Harriet finds herself laughing with him.

They recall a previous meeting at Penn, where they both studied before transferring. The conversation grows unexpectedly intimate, and Ben admits that though he comes from immense privilege, he’s broke.

His trust fund is depleted, and no one in his family knows. He trusts Harriet enough to tell her, even though she could exploit the information.

Harriet warns him against such blind faith, but his belief in her sincerity breaks through her defenses. They part as tentative friends, promising to look for jobs together.

A week later, the story shifts to Ben’s perspective. On a subway to New York, he reflects on leaving Philadelphia behind and the suffocating expectations of being a Cobalt.

He moves into his brothers’ apartment, where tensions simmer. Charlie, the sharp and distant one, greets him with hostility, while Eliot and Tom welcome him more warmly.

Beckett, his gentle older brother, urges him to stay, but Ben resists relying on them. Secretly, he’s struggling with guilt, financial strain, and the sense that he doesn’t belong anywhere.

When he later texts Harriet about their job plans, it gives him something to look forward to.

In another flashback, Ben steps in when a professor harasses Harriet, discovering that she had previously endured exploitation to protect a friend’s academic standing. Harriet’s resilience and shame are visible, and though she tries to keep him away, she thanks him.

Their connection deepens again when they both apply for a bartending job at a local dive bar, The End of the World. During the interview, the manager dismisses Harriet as unfriendly, but Ben refuses the job unless she’s hired too.

His insistence wins them both positions, and a friendship solidifies into quiet loyalty.

Harriet, though grateful, struggles with self-doubt. Her life is marked by hardship, academic ambition, and loneliness.

Her only relative, Aunt Helena, worries about her isolation, so hearing Harriet speak fondly of a “new friend” moves her deeply. Meanwhile, Ben continues to hide his financial trouble from his family.

They’re attentive and concerned, but his pride prevents honesty. He finds comfort in Harriet’s company and begins to view her as a grounding presence.

Their friendship soon faces a moral divide. Ben learns Harriet euthanizes lab mice for her research, something that collides with his compassion for animals.

He’s shaken and unsure whether to stay close to her. His brother Charlie encourages him to listen before judging, advice that anchors Ben when Harriet finally explains how much the lab work distresses her too.

Understanding softens his stance, and he apologizes. Their reconciliation restores the fragile trust between them.

Amid this, Ben witnesses Beckett’s severe OCD episode one night. The experience terrifies him—he feels helpless as Charlie intervenes with practiced calm.

The moment underscores how deeply mental illness runs in their family and leaves Ben reeling. His father, Connor, later takes him hiking to a fire tower, where they have an honest talk about Ben’s struggles with identity and control.

Connor reminds him that sensitivity is not weakness and that his empathy holds the family together. The conversation marks a turning point for Ben, who begins to accept himself without shame.

Meanwhile, Harriet and Ben’s closeness shifts into something unmistakably romantic. They go ice-skating, where Ben’s skill contrasts with Harriet’s clumsy attempts.

When she falls, he catches and kisses her—a moment that changes their dynamic. They start talking about their uncertain futures: Harriet is torn between medical school and joining a band, while Ben debates whether he can ever return to hockey, the sport that once defined him.

They support each other through indecision, finding steadiness in shared vulnerability.

The question of housing soon arises. Ben needs a place to live, and Harriet’s options are also dwindling.

When he suggests they move in together, she hesitates, knowing his family stability is vital to his mental health. Around this time, Harriet discovers Ben’s estate lawyer has named her the beneficiary of his assets—a gesture that stuns her.

He explains that it was his way of showing trust, not a plea for obligation. She refuses to use the money, and they leave the topic unresolved.

As winter arrives, Ben invites Harriet to spend Christmas with the Cobalts. Their family dinners are chaotic but affectionate, revealing both the love and pressure surrounding him.

During a meal, Ben confesses he declined a hockey offer because he’s lost his passion. His father brings up a private meeting with the family lawyer, and Ben clarifies that it wasn’t about suicide—it was about guilt after an old assault incident.

The family accepts his honesty, reaffirming unity through a symbolic ritual of togetherness: “Ensemble—Toujours.

Back in New York, Harriet earns a place in the Honors House and moves in. Ben helps her carry boxes, and they joke about future pets and shared living.

When she faces a career decision between music and medicine, he encourages her to follow her heart. She ultimately chooses medicine, knowing it’s her true calling.

In quiet moments, they share memories of childhood, discovering they may have unknowingly crossed paths years ago.

The story closes with a sense of forward motion rather than finality. Ben finds stability living with his brother Tom, while Harriet continues pursuing her medical ambitions.

Their worlds, once filled with loneliness and guarded walls, now pulse with connection, care, and the tentative courage to begin again. Burn Bright ends not with grand declarations but with quiet certainty—that healing and love can coexist even in imperfect, uncertain spaces, and that sometimes, the smallest acts of trust can illuminate the darkest corners of one’s life.

Characters

Harriet Fisher

Harriet Fisher stands at the heart of Burn Bright as a young woman shaped by isolation, anxiety, and a fierce internal strength. A freshman at Manhattan Valley University, she is socially guarded, weighed down by past trauma, and plagued by self-doubt that often manifests in her discomfort around people and her constant vigilance against ridicule.

The opening incident—where she is harassed at a party—immediately frames her as someone who has long been made to feel powerless, yet her reactions show not fragility but survival instinct. Harriet’s relationship with Ben Cobalt becomes the central force that challenges her to open up to vulnerability without surrendering her independence.

Over the course of the novel, Harriet evolves from a self-protective, emotionally walled-off individual into someone capable of trust, affection, and moral courage. Her pragmatic intelligence and empathy become more visible as she takes responsibility for difficult choices—like confronting her own participation in morally gray situations (the arrangement with Professor Turner) and wrestling with the ethical implications of her lab work involving animal euthanasia.

Her growing emotional maturity is defined not by her dependence on Ben but by her ability to engage with him as an equal, someone who sees his fragility and mirrors it with her own. Harriet’s arc becomes one of quiet empowerment: a journey from surviving to living fully, from fear of rejection to acceptance of connection.

Ben Cobalt

Ben Cobalt embodies the novel’s exploration of emotional vulnerability beneath inherited privilege. As a member of the illustrious Cobalt family, he carries the burden of fame, expectation, and comparison.

However, Burn Bright reveals a young man fractured by guilt, perfectionism, and the lingering effects of trauma—his OCD and internalized sense of inadequacy making him both tender and tormented. Despite his wealth and striking public image, Ben’s emotional honesty and moral integrity distinguish him from the archetype of the golden boy.

His decision to confide his financial crisis in Harriet early on sets the tone for his defining trait: radical openness, even when it risks rejection.

Ben’s compassion often borders on self-sacrifice. He takes emotional responsibility for his siblings’ pain—especially Beckett’s OCD episodes and Audrey’s struggles—while suppressing his own needs.

His relationship with Harriet serves as a mirror that reflects both his yearning for intimacy and his fear of causing harm. Through her, Ben learns that love need not be an act of penance but of mutual care.

His scenes with his father, Connor Cobalt, crystallize his transformation: he learns to view his empathy and doubt not as weaknesses but as essential parts of his humanity. By the end, Ben’s arc resolves into acceptance—he learns to occupy his space in the world, not as the Cobalt heir, but as Ben: flawed, feeling, and incandescently alive.

Beckett Cobalt

Beckett Cobalt is portrayed as the emotional axis of the Cobalt siblings—disciplined, artistic, and deeply afflicted by OCD. His ballet training and precise self-control contrast sharply with his debilitating compulsions, revealing the duality of his existence: grace and torment coexisting in fragile harmony.

Through Beckett, the novel sensitively portrays mental illness not as a defining tragedy but as part of the broader emotional ecosystem of the Cobalt family. His relationship with Ben is a delicate mix of love and guilt, rooted in shared trauma and mutual misunderstanding.

Beckett’s late-night breakdown, witnessed by Ben, acts as a mirror moment for both brothers: Beckett embodies the external expression of what Ben internally suppresses. Their bond evolves into one of silent understanding—a reminder that healing in Burn Bright is communal, not solitary.

Charlie Cobalt

Charlie Cobalt is the intellectual and emotionally distant brother whose sharpness often conceals deep pain. His strained relationship with Ben stems from an old accident that left them both psychologically scarred.

Charlie’s interactions oscillate between cruelty and care, reflecting his own inability to process vulnerability. Yet his quiet moment of empathy—when he listens to Ben’s moral conflict about Harriet’s lab work—reveals a side rarely seen by others: protective, perceptive, and fiercely loyal beneath layers of cynicism.

Charlie represents the kind of love that doesn’t articulate itself through warmth but through attentiveness. In the end, his offer of solidarity during the family’s “Ensemble” ritual underscores his evolution from estranged brother to anchor, reaffirming the Cobalt family’s enduring unity.

Eliot Cobalt

Eliot, the performer and dramatist among the Cobalts, brings levity to the emotional heaviness surrounding Ben. His theatricality and humor serve as both coping mechanisms and bridges of affection.

Though often seen as flamboyant and unserious, Eliot’s kindness and empathy toward Ben are consistent; he diffuses tension, makes space for vulnerability, and ensures that humor becomes a form of healing rather than denial. Eliot’s willingness to share his room with Ben later in the novel captures his deep sense of familial devotion and understanding—a reminder that love, in this family, is often expressed through small acts of accommodation rather than grand declarations.

Tom Cobalt

Tom represents chaos, rebellion, and authenticity. A musician with a restless spirit, he contrasts Ben’s emotional fragility with unapologetic confidence.

Yet Tom’s relationship with Ben reveals that even he recognizes and respects Ben’s boundaries and depth. His lighthearted rivalry—culminating in their coin flip for a shared room—underscores the sibling dynamic of competition rooted in affection.

Tom’s subplot with Harriet, offering her a place in his band, serves to challenge her self-definition: his presence tests her priorities between passion and purpose. Tom, in many ways, symbolizes temptation—the allure of freedom without structure—and his eventual respect for Harriet’s decision reinforces the novel’s theme of self-determination.

Connor Cobalt

Connor, the patriarch and moral compass of the Cobalt family, anchors the story’s intergenerational dialogue about strength and vulnerability. His hike and conversation with Ben form one of the emotional keystones of Burn Bright, reframing weakness as wisdom and doubt as part of courage.

Connor’s calm rationality contrasts with Ben’s emotional volatility, but it is precisely this contrast that allows healing: he meets Ben where he is, not as a father asserting control, but as a man acknowledging another man’s pain. Through Connor, the novel asserts that emotional intelligence is an inheritance far more valuable than money or status.

Audrey Cobalt

Audrey’s presence, though less central, casts a shadow of fragility and familial concern. Her overdose and subsequent behavior reveal the generational impact of expectation and emotional suppression within the Cobalt legacy.

For Ben, Audrey is a symbol of guilt and helplessness—someone he wishes to protect but cannot save. Her storyline reinforces one of the book’s core truths: that love, even when unconditional, cannot always mend another’s pain.

Yet her inclusion deepens the realism of the Cobalt family dynamic, grounding it in shared struggle rather than perfection.

Professor Turner

Professor Turner represents exploitation masked as authority. His manipulative “agreement” with Harriet exposes the vulnerability of young women navigating academic power structures.

Turner’s predatory behavior is not merely an isolated act of villainy—it contextualizes Harriet’s guardedness and her complex sense of moral guilt. His presence early in the narrative shapes Harriet’s distrust of men and institutions, making her eventual trust in Ben all the more significant.

Turner functions as the embodiment of systemic rot, serving as the foil to Ben’s decency and emotional intelligence.

Eden and Aunt Helena

Though secondary, Eden and Aunt Helena form Harriet’s limited support network and act as narrative mirrors for her loneliness. Eden, as her roommate, provides a glimpse into the ordinary collegiate life Harriet feels alienated from, while Aunt Helena represents unconditional love tempered by sorrow.

Their roles, though small, illuminate the scale of Harriet’s isolation and the courage it takes for her to let Ben into her world. Helena’s emotional reaction upon hearing that Harriet has made a friend encapsulates the novel’s quieter triumphs: connection as salvation.

Themes

Emotional Vulnerability and the Strength in Sensitivity

In Burn Bright, emotional vulnerability is portrayed as both a challenge and a defining strength for the characters, especially Ben Cobalt. Growing up in a family celebrated for excellence, control, and prestige, Ben’s sensitivity often makes him feel like the weak link.

Yet this emotional openness becomes the foundation for his growth and his ability to form genuine human connections. The narrative constantly returns to how Ben’s heart—his empathy, self-doubt, and instinct to nurture—sets him apart from the relentless ambition of the Cobalt legacy.

His struggles with OCD and guilt are not shown as flaws to be overcome but as integral parts of his humanity. Through his relationship with Harriet, his vulnerability ceases to be a source of shame and instead becomes the bridge through which intimacy and understanding flourish.

Harriet, too, embodies a quieter version of emotional fragility—her social anxiety, discomfort in crowds, and history of isolation form a protective shell around her. As the story progresses, both characters learn that openness requires courage, and that sharing one’s internal chaos is not weakness but trust.

The theme underscores the idea that gentleness in a world obsessed with power is an act of resilience, and that emotional honesty—especially between two people accustomed to hiding—can be transformative.

Family Expectations and Individual Identity

The shadow of the Cobalt dynasty looms heavily over Ben’s life, creating a constant tension between familial duty and personal autonomy. His surname is both armor and burden, granting him fame but erasing individuality.

The expectations to uphold the family’s image, to succeed without faltering, and to mirror the achievements of his siblings become emotional weights he struggles to carry. Ben’s decision to transfer universities, his financial struggles, and his secret from his family reflect a desire to define himself outside the family’s narrative.

The family dinners, traditions, and watchful eyes reveal a culture of love entwined with performance—a place where affection is genuine but measured against legacy. This pressure manifests in his internal conflicts about masculinity, self-worth, and success.

The story, however, does not vilify the family; instead, it shows that love and pressure often coexist. Connor Cobalt’s conversation with his son at the fire tower reframes strength not as dominance but as authenticity, granting Ben permission to embrace his own form of resilience.

Through this evolution, Burn Bright captures the universal struggle of children raised in the shadows of greatness—learning to honor their lineage without losing their sense of self.

Isolation and the Need for Connection

Both Harriet and Ben are defined by a profound sense of loneliness that shapes their behavior and decisions. Harriet’s isolation is self-imposed, born from trauma and mistrust; she exists at the margins of social circles, choosing solitude as safety.

Her reluctance to attend the frat party and her discomfort in forming friendships speak to a deep-seated fear of exposure and rejection. Ben, though constantly surrounded by people—fans, family, and peers—feels equally isolated, his emotional transparency misunderstood in environments built on confidence and composure.

When the two meet, their connection becomes a sanctuary, an unspoken recognition of shared loneliness. Their conversations in bathrooms, subway rides, and classrooms are intimate not because of romance alone but because they allow mutual visibility—each sees the other beyond external perception.

The book portrays connection as something fragile and earned, not through dramatic gestures but through moments of stillness and understanding. The story suggests that true companionship arises when one feels safe enough to be ordinary, unguarded, and real.

Through their growing friendship and affection, isolation becomes less a symptom of brokenness and more a reminder of what it means to crave belonging in a world that constantly demands perfection.

Morality, Boundaries, and Forgiveness

Moral ambiguity permeates Burn Bright, particularly through the choices characters make under emotional strain. Harriet’s past encounter with Professor Turner—sacrificing her own dignity to protect a friend—exposes the painful complexity of moral decision-making.

Her action is neither celebrated nor condemned; instead, it forces readers to confront the blurred line between survival and compromise. Similarly, Ben’s confrontation with his own mistakes, his violence in the past, and his judgment toward Harriet’s lab work push him toward moral introspection.

The novel treats morality as deeply human—defined less by absolutes and more by empathy and accountability. Forgiveness becomes an evolving process rather than a single act; Ben learns to forgive himself for not being the flawless Cobalt, while Harriet begins forgiving herself for the ways she’s coped with pain.

Their conversations about ethics in science, violence, and love are not theoretical but personal—each trying to navigate how to remain good in a complicated world. The story’s moral heartbeat lies in its refusal to simplify right and wrong, instead insisting that compassion must guide judgment.

Through their growing understanding of each other, forgiveness is not presented as weakness but as an act of self-restoration.

Love as Redemption and Mutual Healing

At its core, Burn Bright is a love story rooted in healing. Ben and Harriet’s relationship unfolds not through grand gestures but through quiet moments of shared vulnerability—studying together, tending to plants, exchanging small acts of care.

Their bond becomes a mirror reflecting their insecurities, forcing each to confront personal wounds. Love here is not an escape from pain but a space to face it safely.

Ben’s compassion challenges Harriet’s belief that she must endure everything alone, while her steady presence helps him find stability amid mental chaos. Their dynamic resists the typical savior trope; they do not fix each other but grow in each other’s presence.

The novel treats love as an evolving, imperfect process that requires self-awareness and honesty. Even their conflicts—like Ben’s struggle with Harriet’s lab work—serve as catalysts for empathy and communication.

In the end, their connection symbolizes how affection can coexist with fear, and how trust can be built in small, imperfect increments. Burn Bright portrays love not as a cure but as a promise—that even amidst fragility, two people can choose each other, not because they are whole, but because they are learning how to be.