Cabin: Off the Grid Summary, Analysis and Themes

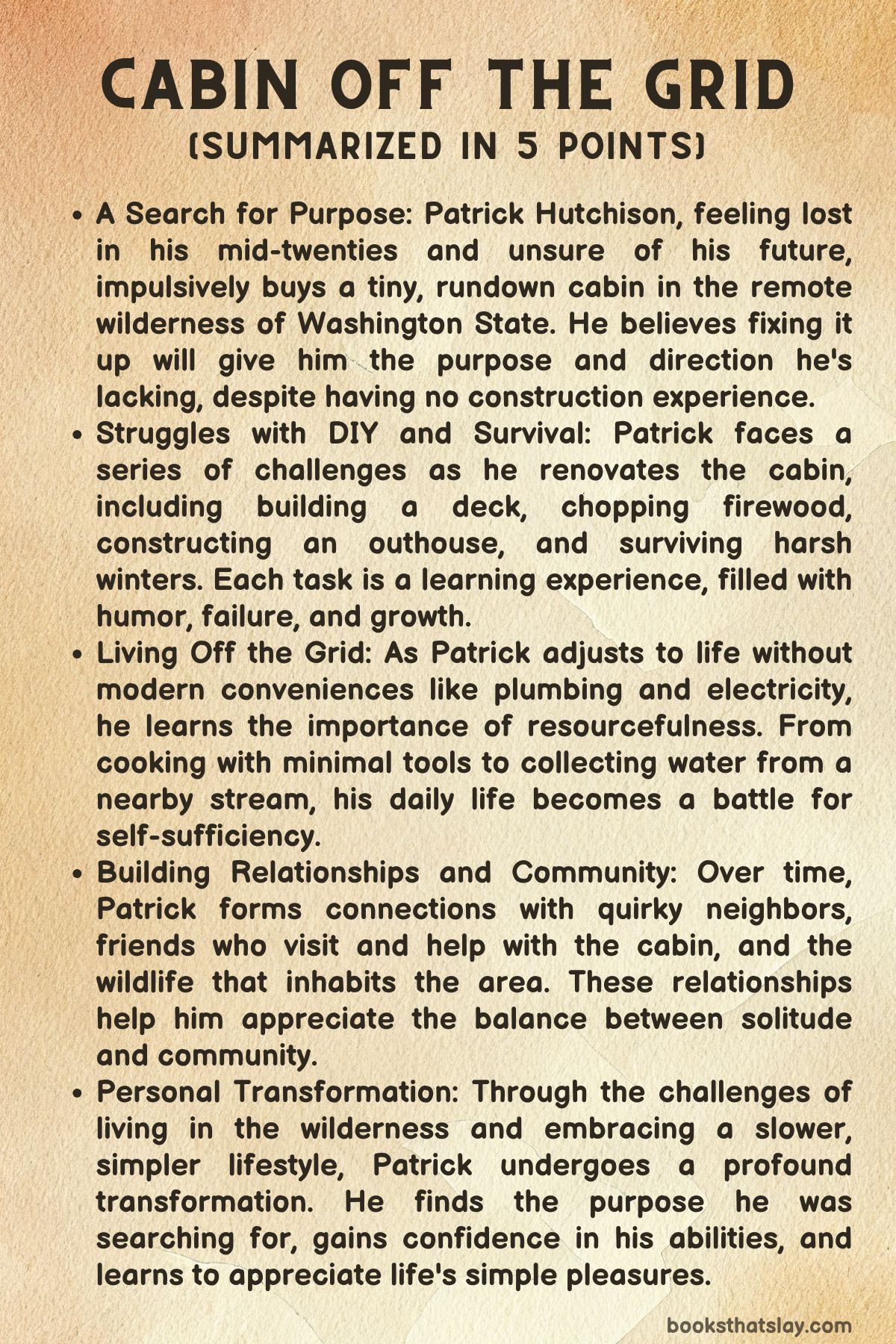

Cabin: Off the Grid Adventures with a Clueless Craftsman by Patrick Hutchison is a witty, vulnerable, and deeply personal memoir chronicling one man’s attempt to reclaim meaning, self-worth, and joy through the restoration of a crumbling cabin in the woods of Index, Washington. At its core, the book is about finding transformation through imperfection, about learning with your hands what the modern world teaches us to forget.

Through a series of missteps, friendships, hard-earned lessons, and oddly endearing failures, Hutchison brings to life the pursuit of a more grounded, deliberate existence away from the disillusionment of office life and societal expectations.

Summary

Patrick Hutchison begins his story in a state of stagnation, caught between the expectations of adulthood and his own unfulfilled ambitions. While his peers settle into steady careers and family life, he finds himself drifting between unsatisfying jobs, his dream of becoming a gonzo travel journalist reduced to disillusioned copywriting.

In the midst of a quarter-life crisis, he becomes fixated on the idea of purchasing a cabin—a symbolic gesture of maturity and independence, unburdened by conventional milestones.

He discovers a $7,500 cabin on Craigslist in the forested town of Index, Washington. The structure is barely functional, little more than a shack with no utilities, foundation, or insulation.

Yet its imperfections speak to him. Enchanted by its rustic charm, he contacts the owner, a mellow tugboat captain named Tony, and decides to buy it despite having no funds.

His mother reluctantly agrees to lend him the money, and the deal is made with a handshake and a visit to a UPS store. The transaction feels absurdly informal for something so life-changing.

Armed with zero carpentry experience, Patrick confronts the daunting reality of renovation. From researching power tools to wrestling with confusing product specifications, every step into this unfamiliar world is a challenge.

He eventually equips himself with basic tools and makes his first trek to the cabin, overwhelmed yet energized by the scope of what lies ahead. He enlists his friends—none of them skilled laborers—for a work weekend, and they tackle foundational projects like flooring, decking, and outhouse construction.

Mistakes are plentiful, but so is the camaraderie. Naming their trench “Badger Creek” and warming themselves by a fire, they celebrate their small victories.

The cabin quickly grows into more than a construction site. It becomes a laboratory for self-discovery and community, a retreat from digital overstimulation and modern monotony.

Each chore, from water hauling to lantern lighting, demands presence and intention. This rustic lifestyle reintroduces Patrick to simple pleasures, grounding him in a way that city life and office work never could.

As he gets to know the area and its eccentric residents, he meets Murphy, a quirky neighbor who initially seems intimidating but soon proves to be part of the town’s rugged charm. Their interactions solidify Patrick’s feeling of belonging.

Over time, the cabin becomes a sacred space, built not just of timber and tools, but of shared effort, laughter, and memories.

One of the most transformative moments comes during the installation of the woodstove. The process is chaotic and nerve-wracking, beginning with failed research attempts and laughably expensive contractor quotes.

Refusing to spend nearly as much as the cabin’s cost on installation, Patrick goes the DIY route, struggling through hardware stores, misfitting chimney parts, and indifferent employees. Salvation comes through McLendon’s, where he finally finds the necessary components.

To execute the installation, he hires Ray, an unconventional yet affable local carpenter. Ray’s methods are improvisational, sometimes eyebrow-raising, but effective.

With his help, the stove is installed, albeit crookedly, and for the first time, the cabin becomes truly livable. The stove provides warmth and ambiance, symbolizing Patrick’s hard-won self-reliance.

As he learns to master the stove’s quirks, the cabin transforms further—with a futon, blankets, a TV tray, and other modest comforts reminiscent of childhood campouts.

Despite its roughness, the cabin becomes a haven from the fluorescent-lit monotony of his previous life. Patrick finds himself dreaming of upgrades but hesitates, fearing that too much refinement would rob the cabin of its soul.

The woodstove is not just a source of heat—it is the beating heart of a simpler, more intentional way of living.

The backstory of the cabin itself adds a layer of history and humor. It was built partially on the wrong lot by a man named George, then inherited and improved by Chris, who, upon learning he didn’t technically own most of it, graciously allows Patrick to proceed with his plans.

This spirit of generosity sets the tone for many of the relationships Patrick forges in Index.

Renovation continues, sometimes with care, sometimes through “jazz carpentry”—improvised and intuitive. He works with friends like Bryan and Todd, whose presence brings both moral support and comic relief.

Whether they’re fixing rot or tripping on mushrooms, each experience is tinged with deeper emotional insight. The physical effort becomes therapeutic, each screw and nail a form of self-expression and healing.

As Patrick navigates repairs, social connections blossom. He befriends his neighbor Mike, who, after his own cabin collapses during an ill-fated repair, turns its ruins into foundation fill for his next build.

Their mutual respect and easy rapport exemplify the type of unexpected bonds that flourish in this off-grid enclave. Another friendship with Andy, a local stonemason, highlights the supportive network slowly forming around Patrick.

Throughout these seasons of transformation, the cabin becomes a mirror of Patrick’s personal growth. What began as a desperate distraction becomes a life-defining mission.

He begins to recognize the limitations of his former life and embraces the rewards of a hands-on, grounded existence. The cabin is filled with artifacts of significance—gifts from friends, heirlooms, and remnants of projects—each piece imbuing the space with memory and identity.

Eventually, the scale of his ambitions grows. Patrick and Bryan construct a second, more elaborate cabin, which financial realities force them to sell.

This moment marks a turning point. Recognizing that he cannot cling to the past indefinitely, Patrick prepares to sell his beloved original cabin as well.

Though the decision is painful, he understands it’s necessary for growth. He leaves behind a heartfelt letter for the next owner, passing along the lessons and love embedded within every board and beam.

The memoir closes not with triumph, but with quiet understanding. Patrick’s cabin, affectionately called Wit’s End, has reshaped him.

It provided sanctuary, purpose, and clarity. Though he walks away, he carries with him a new sense of identity—formed not in office cubicles or career ladders, but in muddy crawlspaces, fire-lit rooms, and the endless rhythm of building something meaningful with his own two hands.

The cabin was never just about wood and nails—it was about becoming someone more grounded, more awake, and finally, more whole.

Key People

Tony

Tony, the original owner of the cabin, is a minor but crucial catalyst in the story’s opening act. A tugboat captain by trade, Tony embodies the relaxed and slightly anarchic spirit of off-grid living.

His willingness to sell the rundown property with little fanfare or concern for its impracticalities signals a departure from the conventional real estate model. Instead of contracts and inspections, the transaction is sealed with a handshake and a cashier’s check—an exchange that reflects both Tony’s laid-back demeanor and the cabin’s status as an unconventional dwelling.

Though he does not play a recurring role in the narrative, Tony represents the beginning of the narrator’s transformation. His brief but memorable appearance situates the reader in a world governed not by bureaucracy, but by personal instinct, risk, and gut-driven decisions.

Ray

Ray is perhaps the most eccentric and delightful supporting character in the memoir. Discovered through an online listing, he is a carpenter of ambiguous credentials, described as both chaotic and indispensable.

His appearance signals the shift from planning to action, especially during the installation of the woodstove. Ray brings with him not just tools and know-how, but an energy of unfiltered enthusiasm and rugged improvisation.

He operates largely on intuition, using tools like the Sawzall with fearless abandon and displaying an uncanny ability to make things work, even if they don’t look quite right. His presence is vital not only for the technical progress he facilitates but for the camaraderie he builds with the narrator.

Ray’s cheerful disregard for conventional aesthetics reinforces a central theme of the book: that perfection is less important than function, joy, and shared labor. His motto—“the cabin is, not the chimney”—becomes an emblem of this unorthodox, deeply personal journey.

Bryan

Bryan is one of the narrator’s closest companions and a consistent presence throughout the memoir’s various construction phases. Unlike Ray, Bryan shares the narrator’s initial cluelessness but matches it with a deep sense of loyalty and good humor.

Their bond is forged through joint endeavors ranging from “jazz carpentry” stair-building to trippy, philosophical reflections during a psychedelic mushroom trip. Bryan’s value lies not in technical skill, but in emotional support—he provides the narrator with laughter, validation, and a sense of shared adventure.

Their teamwork reflects the spirit of communal craftsmanship, where the outcome is secondary to the process. Bryan’s willingness to show up, to engage in both mundane and surreal tasks, and to partake in moments of emotional vulnerability, positions him as both a co-builder of the cabin and a co-architect of the narrator’s evolving sense of belonging and identity.

Kate

Kate is a quietly significant figure in the narrator’s life, appearing in the later stages of the story as both romantic partner and co-adventurer. Her presence injects warmth and a sense of domestic intimacy into the rustic world of the cabin.

Through shared projects and quiet companionship, she helps reinforce the narrator’s growing capacity for emotional connection and stability. One memorable moment—an accidental injury during a roof repair—underscores the unpredictable, messy, and sincere nature of their relationship.

Kate doesn’t just join the journey; she deepens it. Her participation brings dimension to the narrator’s quest for meaning, proving that relationships, like cabins, can be built slowly, imperfectly, and with care.

Her acceptance of the cabin’s rough edges mirrors the narrator’s own evolving philosophy of life.

Mike

Mike, the narrator’s neighbor, evolves from a potentially threatening unknown into a quietly anchoring presence in the story. Initially introduced after purchasing a nearby derelict cabin, Mike becomes a symbol of grounded generosity and community.

His unassuming demeanor and practical wisdom make him an ideal neighbor in a setting that thrives on mutual reliance. Whether checking on the narrator during absences or commiserating over cabin-related disasters, Mike represents the natural order and quiet solidarity of off-grid life.

His handling of his own cabin collapse—with a mix of pragmatism and poetic acceptance—deepens the book’s metaphorical layers, showing how even ruin can be repurposed, literally buried and built upon. Mike reinforces the narrative’s central theme: that resilience often comes not from mastery, but from kindness, flexibility, and the willingness to start again.

Chris

Chris serves as a transitional figure in the cabin’s strange history—someone who bought the lot without realizing most of the cabin he believed he owned actually sat on another’s land. Despite this frustrating revelation, Chris is generous and unbothered, allowing the narrator to repurpose siding and showing no bitterness over the mistake.

His ability to laugh off what could have been a source of conflict demonstrates a rare grace. Chris’s attitude reflects the ethos of the Index community, where eccentricity and acceptance override pettiness.

Though his role is brief, he exemplifies a foundational value in the book: that community is often defined less by formal agreements and more by unspoken generosity and shared eccentric dreams.

Todd and Kellen

Todd and Kellen appear as part of the narrator’s extended circle of support—friends who may lack carpentry expertise but contribute time, muscle, and morale. Todd’s involvement, particularly in the rain-soaked task of replacing rotten joists, emphasizes the bonds forged in shared discomfort.

These friendships—weathered in literal and figurative mud—ground the memoir in themes of cooperation, humility, and enduring affection. Kellen’s contributions further reinforce the idea that building something real is less about technical skill and more about spirit, loyalty, and the stories shared between hammer swings.

Both characters represent the “clueless craftsmen” of the book’s subtitle: imperfect, learning as they go, and all the more admirable for their willingness to dive in anyway.

Themes

Self-Reliance and the Learning Curve of Craftsmanship

What begins as an impulsive escape for the narrator in Cabin Off the Grid gradually evolves into a raw experiment in self-reliance. The decision to purchase a run-down cabin without prior experience in construction forces the narrator to confront his limitations in the most immediate, physical sense.

Each task—whether it’s sourcing power tools, digging trenches, or installing a woodstove—becomes a hands-on lesson in self-education. Unlike abstract office work that leaves little visible result, craftsmanship in the woods produces clear progress, even if riddled with flaws.

The narrator starts with no understanding of carpentry and must stumble his way through instruction manuals, YouTube tutorials, and advice from strangers. This disorientation becomes a foundational part of his personal growth; he learns to accept failure not as a reason to quit, but as a requirement for figuring things out.

The cabin’s every flaw—its rotted wood, lack of electricity, and slanted construction—becomes both a literal and symbolic mirror for the narrator’s unfinished and imperfect self. The success he finds is not in reaching polished results but in embracing the discomfort of not knowing and forging his way forward through action.

Over time, the cabin becomes a kind of informal apprenticeship, offering the narrator a new identity rooted in competence and autonomy, cultivated not in a classroom but in muddy trenches and sawdust-filled rooms.

Masculinity, Identity, and Reconstructing Adulthood

The cabin represents a redefinition of adulthood for a man disenchanted with traditional paths. While friends pursue conventional milestones like careers, marriage, and graduate degrees, the narrator finds himself disoriented, detached from such linear progression.

His move to buy and rebuild a cabin emerges from this tension—an attempt to reclaim some sense of legitimacy on his own terms. Instead of mortgages or office promotions, adulthood becomes associated with learning to split wood, cook over a fire, or repair a roof leak in the rain.

The process is not performative masculinity, filled with bravado, but something more vulnerable: an honest negotiation with incompetence, physical labor, and friendship. The narrator’s identity reshapes through the grit of trial-and-error projects and the surprising tenderness of community.

Sharing beers with friends after a long workday, laughing through failed carpentry, or depending on a semi-competent local handyman—these experiences come to define a version of masculinity that values presence, humility, and effort over mastery. The cabin, in this way, is not merely a backdrop but an active force in constructing a new model of what it means to grow into oneself as a man, one who does not conquer nature or skill but coexists with it while learning.

Community, Friendship, and Shared Labor

Although the cabin project begins as a solitary journey, it quickly becomes a shared endeavor. The arrival of friends—none of whom are skilled laborers—adds depth to the narrative, revealing how shared physical labor becomes a powerful means of connection.

Together, they tackle absurd, often inefficient renovations, improvising fixes and laughing through their inexperience. These moments generate a kind of collective joy that emerges not from the results of their work but from the act of working together.

The presence of colorful locals like Ray and neighbors like Mike further extends the idea of community beyond the narrator’s inner circle. Ray’s unorthodox methods and Mike’s slow transformation from a suspicious figure to a dependable friend show how openness to imperfection can lead to genuine bonds.

This community is not idealized; it is rough-edged and sometimes ridiculous, but it thrives on generosity and trust. Shared mistakes, ridiculous solutions, and even psychedelic nights become part of the lore they build together.

The cabin thus acts as a social hearth, where camaraderie is stoked not by smooth experiences but by the willingness to try, to mess up, and to stay present in each other’s efforts.

The Spiritual and Therapeutic Power of Place

As the narrator returns to the cabin again and again, it transforms into a spiritual anchor. The cabin’s off-grid setting, far removed from fluorescent offices and algorithmic scrolling, insists on a slowness that has become alien in the modern world.

Basic tasks—fetching water, lighting a fire, chopping wood—require focus, rhythm, and repetition, becoming small meditations in themselves. These rituals gradually shift the narrator’s understanding of peace and fulfillment.

Time spent at the cabin is not about escape so much as a return to something elemental: a grounded, hardscrabble sense of being that is deeply tied to place. The decision to decorate with objects imbued with personal significance, like his father’s moccasins or handmade pottery, layers the cabin with emotional meaning.

It becomes a sacred space not in the religious sense, but in the sense of being deliberately constructed, cared for, and filled with memory. Even the flaws—the leaky chimney, the rotting joists, the sagging floorboards—gain a kind of emotional value.

They mark the process of living, of learning, and of loving something enough to make it better, even when it’s hard. This relationship with the cabin becomes a quiet counter-argument to consumerism’s promises of ease.

It’s a slow burn of transformation, where meaning accumulates not through acquisition, but through intentional presence.

Letting Go and the Cost of Growth

The decision to sell the original cabin near the end of Cabin Off the Grid is a wrenching one, filled with emotional complexity. After years of investment—emotional, physical, and social—the narrator is forced to recognize that holding on might limit future possibilities.

The cabin, though a haven, has also become a container. To grow, he must risk detachment, which echoes one of the central tensions of adulthood: learning when to persist and when to move on.

The act of letting go is not framed as failure, but as a necessary release, a gesture of respect toward the journey that the cabin initiated. It has already served its purpose—guiding him toward purpose, friendship, identity, and vocation.

Moving on becomes an acknowledgment that the cabin’s power lay in what it awakened, not in the structure itself. Leaving a note for the new owner feels ceremonial, a way of honoring the space while acknowledging that transformation is ongoing.

The narrator’s journey is not a neat conclusion but a relay baton passed from one chapter of life to the next. The loss, though painful, makes space for continued becoming.

In this way, the theme of letting go is not about absence but about the courage to trust that the lessons will carry forward, even after the door is closed.