Christmas at the Ranch Summary, Characters and Themes

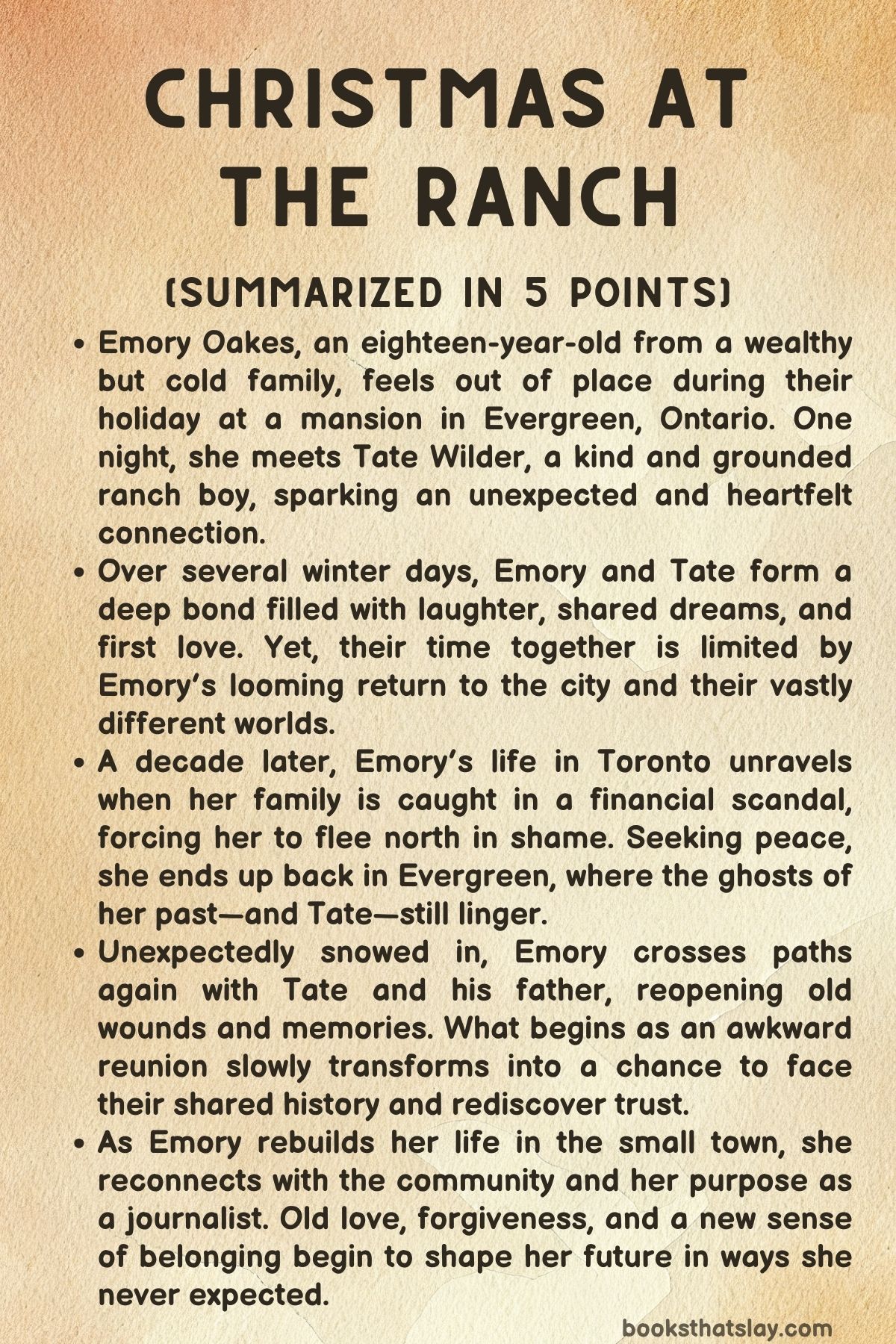

Christmas at the Ranch by Julia McKay is a tender story of love, loss, and rediscovery set against the snowy backdrop of Evergreen, Ontario. The novel follows Emory Oakes, a once-sheltered city girl whose life takes a sharp turn when family scandal drives her back to the small town where she first found belonging—and love—ten years earlier.

There, she reunites with Tate Wilder, the rancher’s son she never forgot. As the two face old wounds, family secrets, and the weight of forgiveness, they rediscover what truly matters: home, honesty, and the courage to begin again.

Summary

At eighteen, Emory Oakes finds herself spending Christmas with her wealthy but fractured family at a rented mansion in Evergreen, Ontario. Surrounded by relatives who criticize her for being too cautious and dull, she seeks escape one icy night.

Following an eerie howling from the frozen lake, she meets Tate Wilder, a kind and grounded local boy who works on his family’s horse ranch next door. The two instantly connect, bonding over their differences—her lonely privilege and his simple, fulfilling rural life.

Tate introduces her to the ranch, his horses, and a donkey named Kevin, sharing stories about his late mother. Their conversations stretch into dawn, and their growing attraction leads to Emory’s first real kiss.

Over the following days, Emory and Tate secretly meet again and again. They explore snowy trails, talk about dreams, and fall deeply in love.

Tate hopes to expand the ranch into a riding school, while Emory dreams of studying journalism. Yet the holidays—and their time together—soon end.

Their story closes with a promise to stay in touch, though fate has other plans.

A decade later, Emory is a 28-year-old journalist in Toronto. Her world shatters when news breaks that her father and cousin have been arrested for large-scale financial fraud through the family company, TurbOakes.

The scandal leaves her devastated, and though she had no part in the crimes, guilt and shame consume her. When her mother pressures her to use her untouched trust fund to pay legal fees, she reluctantly agrees.

Overwhelmed, she drives north aimlessly and ends up in Evergreen—the last place she wanted to return.

There, she finds the once-rented mansion transformed into the Evergreen Inn, run by Reesa and her cheerful daughter Sam. They welcome her without realizing who she is, but when her identity is revealed, Reesa grows cold.

The townspeople lost money in TurbOakes investments, including Gill, a local man who had invested his inheritance. Feeling responsible, Emory prepares to leave, but a snowstorm strands her.

Seeking help at a mechanic’s shop, she unexpectedly runs into Tate’s father, Charlie Wilder. He invites her to the ranch to wait out the weather and mentions Tate is away.

Emory, conflicted but with nowhere else to go, agrees.

At the ranch, memories flood back. Charlie shows her around, introducing her to Star, a horse she once helped deliver.

When a power outage prevents her car repairs, she must stay overnight—ironically, in Tate’s cabin. The cabin feels untouched by time, filled with relics of their shared past.

That night, Tate unexpectedly returns early, and their reunion is awkward and charged. He’s courteous but distant, still harboring pain from years ago.

The tension between them is palpable.

The next morning, Emory tries to leave but ends up crashing her car after swerving to avoid a moose. Tate finds her stranded and insists she come back to the ranch until it’s safe to travel.

Slowly, they begin to interact again. Charlie asks her to help exercise Star, believing the horse trusts her.

Riding again brings Emory peace, but her calm shatters when she sees Tate with Mariella, a beautiful woman she assumes is his girlfriend. Jealous and hurt, Emory decides to leave Evergreen once more.

However, she ends up working for Bruce, the editor of the local paper, the Evergreen Enquirer. She begins writing restaurant reviews and rediscovering her love for storytelling.

One evening at a Chinese restaurant, she unexpectedly runs into Tate again. Their shared meal starts awkwardly but soon turns warm and nostalgic.

Tate apologizes for his earlier coldness, explaining his fears about liability after a lawsuit nearly cost him the ranch. He asks Emory to help retrain Star, who responds uniquely well to her.

Their partnership rekindles their bond, though both tread carefully around old wounds.

Emory’s journalism begins to rebuild her confidence. She writes about the town’s people and businesses, regaining a sense of purpose.

At the same time, her connection with Tate deepens. They spend more time together at the ranch, and their unspoken feelings resurface.

She learns more about his struggles since his mother’s death and the pressures of running the ranch. Despite the emotional distance caused by misunderstanding, their old chemistry lingers.

Through her diary, readers glimpse Emory’s teenage love for Tate and the heartbreak that followed. Years ago, her father’s attempt to buy the Wilder Ranch as an investment had insulted Tate’s family, driving a wedge between the couple.

Emory left town heartbroken, believing she’d ruined everything. Now, faced with the man she never stopped loving, she’s torn between guilt and desire.

Their renewed closeness builds until an accident on a night ride reignites Tate’s trauma over his mother’s death in a riding accident. Terrified of losing Emory, he pushes her away again.

Hurt and confused, Emory returns to her small apartment, where she receives a call from her imprisoned father, who expresses regret for his crimes. His remorse inspires her to stop running from her past.

Determined to move forward, Emory focuses on writing and tries to make amends with those her family wronged. When Tate visits her, they finally speak honestly about everything—their breakup, his mother, and their enduring love.

He confesses he never stopped thinking about her and even tried visiting her in Toronto once but lost his courage. Their emotional reunion leads to reconciliation and a long-awaited kiss.

Their moment is interrupted when Emory’s mother, Cassandra, arrives in Evergreen. She brings a check to repay Gill using what’s left of Emory’s trust fund.

Together, they visit Gill, who refuses the money, showing unexpected forgiveness. The encounter helps Emory and her mother begin healing their fractured relationship.

Cassandra sees her daughter’s newfound happiness with Tate and encourages her to follow her heart.

Later, Tate shows Emory her old diary, which he found years ago and kept safe. Inside are unsent letters he had written to her, revealing he had loved her all along.

Overcome with emotion, they embrace their second chance and spend the night together, finally free from the past. Tate asks her to stay for Christmas, and she says yes.

On Christmas Eve, Emory joins Tate, his father, and the townspeople for the annual Starlight Ride, a magical procession through the snowy forest lit by lanterns and filled with music. Her mother walks beside her, symbolizing forgiveness and new beginnings.

Under the stars, Emory and Tate share a kiss, promising to build a future together.

A year later, Emory writes her final diary entry. She now lives in Evergreen, working full-time at the Enquirer and helping run a foundation for local children.

Her parents are working toward redemption, and she and Tate are engaged. During the most recent Starlight Ride, Tate proposed with his mother’s ring engraved with the words “Hey, City Girl.” Emory said yes—closing one chapter of her life and beginning another, finally home where her story began.

Characters

Emory Oakes

Emory Oakes stands at the heart of Christmas at the Ranch, embodying themes of self-discovery, forgiveness, and emotional resilience. As an eighteen-year-old, she is portrayed as introspective, responsible, and quietly yearning for connection in a world that prizes appearances over authenticity.

Her discomfort within her affluent but fractured family pushes her toward the emotional warmth she finds in Tate Wilder. This early contrast between her stifling city life and the grounded rural world of Evergreen becomes the foundation for her inner transformation.

Ten years later, Emory has grown into a woman burdened by guilt and familial shame, yet still defined by empathy and integrity. Her father’s financial crimes become a mirror for her own moral reckoning—forcing her to decide who she is apart from the Oakes legacy.

Her return to Evergreen symbolizes both physical and emotional refuge, where she confronts old wounds and rediscovers purpose. Emory’s strength lies in her capacity for growth: she learns to forgive her parents, rekindle her first love with Tate, and ultimately choose a life built on honesty, compassion, and belonging.

Her evolution from a lonely teenager to a self-assured journalist and partner marks her as one of Julia McKay’s most richly developed protagonists.

Tate Wilder

Tate Wilder is both Emory’s first love and the emotional anchor of the novel. At eighteen, he represents everything she lacks—stability, sincerity, and connection to something real.

His grounded nature and close bond with his father reflect the earthy values of small-town life. Yet Tate is not without complexity.

The loss of his mother in a riding accident haunts him, shaping his protectiveness and sometimes his fear of emotional vulnerability. His openness and warmth as a teenager evolve into guarded restraint as an adult, scarred by heartbreak and responsibility.

When Emory returns to Evergreen, Tate has matured into a man who carries both pride and pain. His cautious demeanor and fixation on safety—symbolized through his insistence on liability waivers—reflect his trauma and fear of loss.

His rekindled relationship with Emory forces him to confront those fears, bridging the divide between his past grief and present hope. In rediscovering love, Tate learns that vulnerability does not equate to weakness.

His journey from youthful idealism to mature forgiveness stands as a quiet counterpart to Emory’s transformation, completing the emotional symmetry of the story.

Charlie Wilder

Charlie Wilder, Tate’s father, is a pillar of kindness and moral steadiness throughout Christmas at the Ranch. As a widower who has endured loss, he brings a sense of calm wisdom to the tumultuous events around him.

His compassion toward Emory, even after her family’s role in local financial ruin, underscores his generous heart and belief in redemption. Charlie’s relationship with his son reveals both tenderness and tension: he respects Tate’s independence but worries about his emotional isolation.

Charlie functions as a father figure not only to Tate but also symbolically to Emory. His unwavering decency contrasts sharply with the corruption and emotional neglect of Emory’s own family.

Through him, Julia McKay celebrates integrity and empathy as enduring values that transcend social class. Charlie’s home—Wilder Ranch—becomes a sanctuary where healing begins, a space that reflects his nurturing spirit and his quiet understanding of love’s endurance.

Cassandra Oakes

Cassandra Oakes, Emory’s mother, embodies the tragedy of moral blindness and eventual redemption. Initially complicit in the materialism and emotional distance of the Oakes family, she represents the pain of living behind façades.

Her husband’s crimes shatter that world, forcing her to confront the emptiness of her privilege. When she reenters Emory’s life in Evergreen, Cassandra’s vulnerability marks a turning point—her guilt and shame are sincere, and her effort to repay one of the victims becomes an act of moral awakening.

Through Cassandra, the novel explores how love and accountability can coexist. Her willingness to face her daughter honestly opens the path for reconciliation.

By the end, she is no longer a distant matriarch but a mother humbled by experience and capable of genuine affection. Cassandra’s transformation parallels Emory’s, emphasizing the theme that healing often begins with honesty and courage to confront one’s failings.

Mariella

Mariella, introduced as Tate’s supposed romantic partner, initially embodies Emory’s insecurities and misunderstandings. Yet as the story unfolds, Mariella emerges not as a rival but as a professional ally—an instructor who represents progress for Wilder Ranch.

Her presence tests Emory’s emotional maturity, forcing her to discern between jealousy and self-worth. Mariella’s professionalism and kindness highlight the importance of female solidarity in a story otherwise centered on romantic and familial bonds.

By portraying Mariella as capable and supportive rather than antagonistic, McKay resists clichéd depictions of romantic competition. Instead, Mariella’s role subtly reinforces the novel’s broader message about trust and communication—showing how misperceptions can fracture relationships as easily as dishonesty.

Bruce

Bruce, the elderly newspaperman who hires Emory, is a symbol of mentorship and renewal. His gentle humor and steady encouragement help Emory rediscover her passion for journalism and her sense of belonging.

Unlike the corporate world she left behind, Bruce’s small-town newsroom represents authenticity and integrity. Through their friendship, Emory learns that work can be not just survival but service to community.

Bruce’s moral clarity and acceptance also serve as a quiet act of grace. When Emory confesses her family’s crimes, his refusal to judge her affirms the story’s recurring theme of forgiveness.

His character enriches the emotional texture of the novel, grounding Emory’s redemption not just in love but also in purpose.

Gill

Gill, the local restaurant owner ruined by TurbOakes’ financial scandal, personifies the human cost of greed and corruption. Though his livelihood suffered because of Emory’s family, Gill remains dignified and kind, refusing both revenge and pity.

His decision not to accept restitution underscores his integrity and resilience. Gill’s quiet moral strength contrasts sharply with the Oakes family’s downfall and becomes a mirror through which Emory confronts her inherited guilt.

In many ways, Gill represents the conscience of Evergreen—a man wronged yet still rooted in decency. His interactions with Emory illustrate how forgiveness can be more transformative than punishment, reinforcing the novel’s overarching belief in the possibility of grace.

Reesa and Sam

Reesa and her young daughter Sam bring warmth and community to Emory’s reentry into Evergreen. As the innkeeper and her bright, curious child, they offer a sense of home and welcome before Emory’s identity is revealed.

When Reesa discovers who Emory truly is, her reaction captures the deep wounds left by the TurbOakes scandal, yet her eventual forgiveness highlights the capacity for empathy in a close-knit town.

Sam’s innocent affection for Emory provides a subtle but powerful reminder of renewal—the idea that the next generation can embody hope untainted by past mistakes. Together, Reesa and Sam represent the nurturing spirit of Evergreen, reinforcing the novel’s central message: that home is not a place of origin, but a place of acceptance.

Mya

Mya, Emory’s old acquaintance and a local restaurateur’s daughter, acts as both comic relief and emotional bridge in Christmas at the Ranch. Her directness and unfiltered honesty cut through the tension between Emory and Tate, while her warmth helps Emory reestablish her connection to the community.

Mya’s friendship symbolizes the importance of understanding and second chances. She not only helps Emory confront her past but also gives her a sense of belonging beyond romance.

Through Mya, Julia McKay celebrates the bonds of female friendship as an essential element of healing. Her character proves that redemption often depends not on grand gestures, but on the small kindnesses that make forgiveness possible.

Themes

Love and Redemption

Love in Christmas at the Ranch functions not as a fleeting emotion but as a force that transforms brokenness into healing. The relationship between Emory and Tate is marked by youthful passion, painful misunderstanding, and, ultimately, a mature rediscovery that reflects how love endures through time and change.

When they first meet as teenagers, their bond offers Emory escape from the cold superficiality of her family and gives Tate comfort on the anniversary of his mother’s death. Their connection, rooted in authenticity and vulnerability, stands in stark contrast to the artificial world Emory comes from.

Years later, after betrayal and silence, they reunite under the heavy shadow of her father’s crimes. Their love becomes a channel for both to confront past wounds—Tate’s fear of loss and Emory’s guilt over her family’s wrongdoings.

Through forgiveness and emotional courage, they reclaim what once seemed lost. The novel suggests that redemption is inseparable from love—it requires self-awareness, the humility to accept fault, and the willingness to start again.

Emory’s act of returning to Evergreen is both a literal and emotional journey toward forgiveness, not only from Tate but also from herself. By the story’s end, love has matured from impulsive teenage infatuation into a grounded partnership built on trust and shared purpose, proving that forgiveness and emotional honesty can renew even what once seemed beyond repair.

Identity and Self-Discovery

Emory’s journey throughout Christmas at the Ranch is fundamentally one of rediscovering herself. When she first appears as a teenager, she is overshadowed by the expectations and judgments of a family that equates worth with wealth.

The holiday at Evergreen becomes her first taste of authenticity—a glimpse of who she might be outside her family’s influence. As an adult, however, she finds herself lost again, her identity fractured by her father’s scandal and her own disillusionment with city life.

Her decision to flee to Evergreen is not merely escapism; it is an unconscious return to the version of herself that once felt whole. The small-town world, with its quiet rhythms and sense of community, forces her to confront who she truly is beyond her surname or career.

By working at the local newspaper, reconnecting with Tate, and facing the town’s resentment toward her family, Emory begins to define herself through integrity, empathy, and purpose rather than inherited privilege. Her writing becomes symbolic of her reclaimed voice—the ability to tell truth rather than conceal it.

The woman who once felt invisible among her family emerges as someone who belongs, not because of status, but because of authenticity. Her self-discovery is not about transformation into someone new but about returning to her truest self, the girl who stood by a frozen lake and dared to choose sincerity over appearance.

Family and Forgiveness

Family in Christmas at the Ranch is both the source of Emory’s deepest pain and the foundation of her eventual growth. The Oakes family embodies the destructive nature of greed and emotional neglect.

Her father’s obsession with wealth and reputation creates not only public scandal but private wounds that scar his wife and daughter. Yet, amid this collapse, the novel portrays the slow and painful work of reconciliation.

Emory’s relationship with her mother evolves from distance to mutual understanding. Cassandra’s journey from complicity to remorse mirrors Emory’s own movement toward forgiveness.

Their shared decision to repay Gill and face the consequences of their family’s actions marks a turning point—one where moral accountability replaces denial. The contrast between the Oakes and Wilder families reinforces the novel’s message that family is not defined by money or success but by integrity and loyalty.

Charlie Wilder’s steadfast kindness and Tate’s quiet resilience stand as moral anchors, showing what it means to love without condition. Forgiveness, in this context, is not an easy absolution but a deliberate choice to move beyond bitterness.

By the end, Emory’s reconciliation with her parents signifies the healing of an emotional lineage fractured by greed, suggesting that forgiveness is a generational act capable of restoring dignity to even the most broken family bonds.

Class and Belonging

The clash between Emory’s wealthy background and Tate’s working-class world forms a central tension in Christmas at the Ranch. The novel explores how class differences shape identity, relationships, and the perception of worth.

As a young woman, Emory is caught between privilege and isolation; her family’s wealth grants her comfort but denies her emotional connection. Tate, by contrast, embodies self-reliance, rootedness, and moral clarity.

Their love story exposes how class can divide even the most sincere affections. When Emory’s father offers to buy the Wilder Ranch, it humiliates Tate and his family, turning love into a casualty of pride and power.

Years later, the financial scandal surrounding TurbOakes reverses the dynamic—Emory becomes the outcast, burdened by shame, while Tate represents stability. The shift reveals how easily social hierarchies can crumble when integrity replaces arrogance.

Through Emory’s experience in Evergreen, the novel suggests that belonging is not found in wealth or lineage but in honesty and shared values. Her eventual acceptance by the townspeople and her relationship with Tate symbolize the reconciliation of two worlds—the artificial glamour of privilege and the genuine warmth of community.

By choosing to remain in Evergreen, Emory rejects the shallow validation of her old life and embraces a world built on human connection rather than material success.

Healing and Second Chances

At its heart, Christmas at the Ranch is a story about the power of second chances—how people, love, and even entire lives can be rebuilt after failure. Emory’s return to Evergreen is both a reckoning and a renewal.

She confronts the ruins of her past—her family’s disgrace, her lost relationship, and her own guilt—and learns that healing is a process rooted in courage and compassion. The novel treats mistakes not as endpoints but as opportunities for rediscovery.

Tate’s willingness to forgive, despite his past hurt, and Emory’s determination to make amends transform what could have been a story of regret into one of resilience. The ranch itself becomes a metaphor for restoration—a place once scarred by financial and emotional loss that is revived through love and care.

The recurring image of the horse Star, once injured and fearful, mirrors Emory’s own journey; both must learn to trust again. The final scenes, filled with light, snow, and community, suggest that healing is not achieved through isolation but through connection—with others, with nature, and with oneself.

By the end, the promise of a shared future and the symbolism of the engagement ring embody the culmination of every second chance taken—the proof that redemption, when met with honesty and heart, can rewrite even the most broken stories.