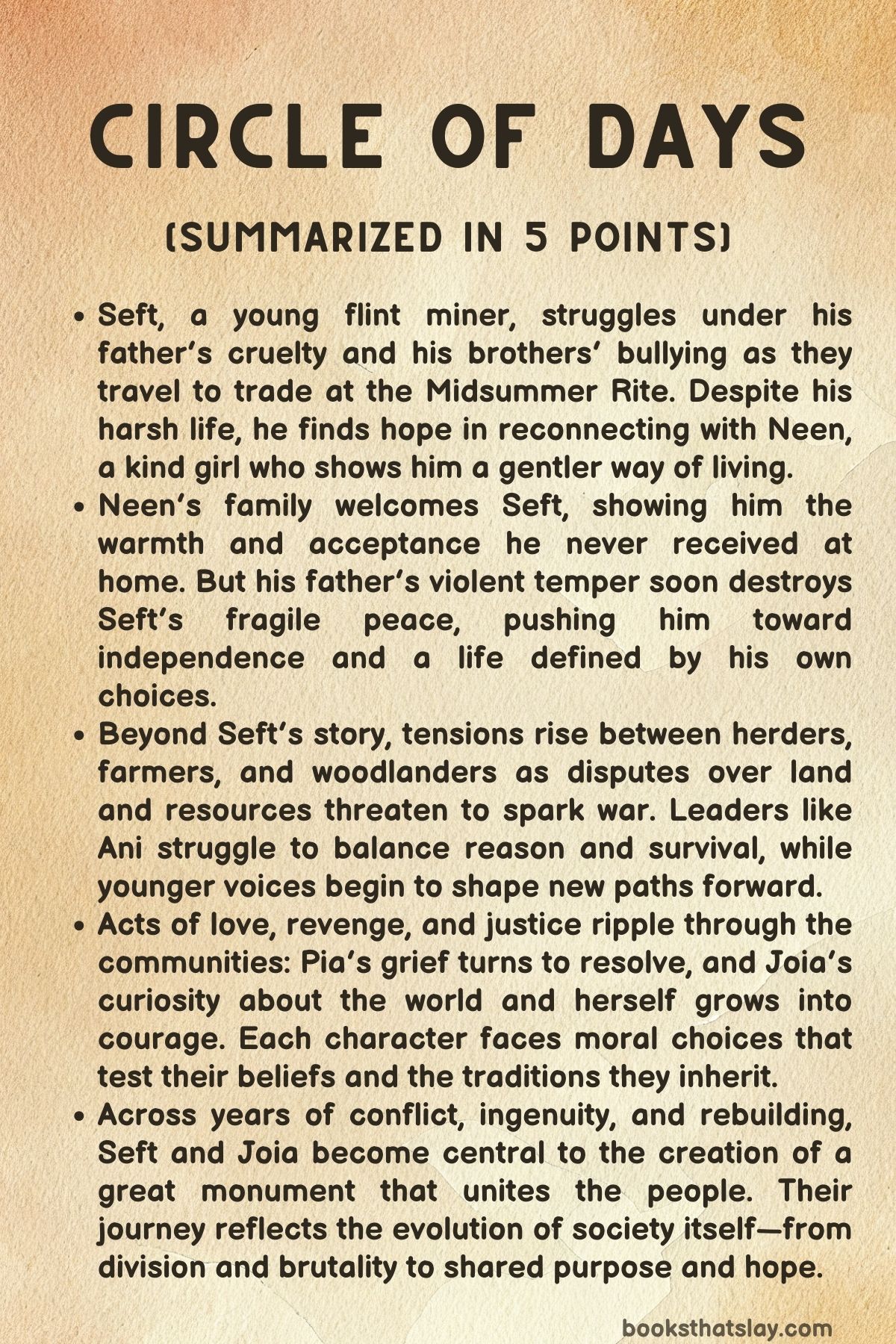

Circle of Days Summary, Characters and Themes

Set in prehistoric Britain, Circle of Days by Ken Follett follows generations of early settlers as they struggle for survival, community, and meaning in a world shaped by ritual, nature, and invention. Through the intertwined lives of miners, herders, farmers, and priestesses, Follett builds an ancient civilization emerging from brutality toward unity and creation.

The story blends daily labor, love, loss, and the drive to build something lasting—the great Monument that will mark humanity’s first step toward organized faith and architecture. It is both an origin tale of human cooperation and a meditation on the balance between violence and progress, tradition and change.

Summary

Seft, a young flint miner, travels across the Great Plain with his domineering father Cog and his brothers Olf and Cam. The family is headed to the Midsummer Rite at the Monument, carrying flints to trade.

Seft, tired of being bullied and beaten, secretly looks forward to meeting Neen, a girl he had connected with during the Spring Rite. His brothers cruelly add more flints to his load to exhaust him, and when he discovers the trick, he throws the extra stones away.

Olf attacks him, but Seft fights back and wounds him. This marks the first time Seft stands up to his family’s cruelty.

At the trading grounds, Seft slips away to find Neen in the nearby village of Riverbend. He encounters her younger sister Joia, who teasingly helps him reach Neen.

When he finally meets Neen, she welcomes him warmly, and they share a quiet walk among the sacred wooden rings. They talk about family, loss, and dreams—Seft’s wish to escape his father’s violence and Neen’s longing for peace after her father’s death.

That evening, Seft is invited to supper with Neen’s family. Her mother, Ani, treats him kindly, and Seft feels what it means to belong.

Later that night, Neen and Seft meet in a riverside grove and make love, believing their union sacred. Seft imagines a future together, but Neen, more grounded, asks him not to assume promises yet.

The next morning, the two join the Midsummer ceremony at the Monument, where priestesses align their chants and dances with the rising sun. It is a moment of awe and order in their wild world.

Seft plans to return for dinner with Neen’s family, but when he rejoins his own kin, his father demands that he leave immediately to guard their flint pit. Seft refuses, determined to see Neen again.

In a violent rage, Cog beats him nearly to death as others watch. The attack sparks outrage—Ani and other elders condemn Cog’s brutality and forbid anyone from trading with him.

Disgraced, Cog and his older sons are forced to leave.

That night, celebration fills Riverbend, but Seft is too wounded and humiliated to enjoy it. While the festival continues, young Joia—Neen’s sister—experiences her own awakening.

Unlike her peers, who flirt and pair off under the festival’s tradition of free love, Joia feels detached from boys. Curious about her difference, she impulsively kisses an older woman, Kae, and feels an unfamiliar pull.

Kae gently tells her that desire takes many forms. Her mother Ani comforts her, assuring her that she is not broken but unique.

Meanwhile, Seft nurses his injuries and works on repairing his family’s pit house. His father mocks him, refusing to see Seft’s innovation in using carved pegs to stabilize a new lintel.

When another miner, Wun, recognizes Seft’s skill and offers him work, Cog refuses. Hungry and despairing, Seft finally runs away at night, hiding in a valley he names Stony Valley.

Watching his family search for him in vain, he plans a new life with Wun.

Beyond the miners, tension brews between farmers and herders. Farmer Yana and her daughter Pia discover that the farmers, led by Troon, have plowed up the Break—the herders’ grazing route to the river.

Ani and other elders warn that this could provoke war. A tense meeting between the two groups nearly leads to violence, but Ani’s wisdom persuades the herders to hold back.

The farmers mistake restraint for weakness, deepening resentment on both sides.

Joia, still restless, becomes fascinated with the priestesses and their secret rituals. With her friends Vee and Roni, she sneaks out before dawn to spy on a sunrise ceremony.

Watching from the shadows, she realizes that the stones and wooden rings are precisely arranged for the sun’s movements. This discovery ignites in her a fascination with knowledge and purpose—an early spark that will shape her destiny.

Far away, tragedy strikes Pia. Living among farmers, she witnesses her husband Han and friend Fell murdered by Stam, a violent farmer.

Stam kidnaps Pia and her baby, forcing her into servitude. When woodlander hunters find Han and Fell’s bodies, they swear vengeance.

Guided by Bez, they capture Stam, bury him alive, and later burn him, restoring what they call “balance. ” Pia returns to harsh life under Troon but remains haunted by loss and the cycle of retribution.

As drought grips the land, farmers and herders clash again. Desperate cattle trample crops while trying to reach the river, sparking another round of bloodshed.

Ani, Seft, and others attempt peace through compromise, proposing a fenced passage—the new Break—so herders and farmers can coexist. Seft’s ingenuity helps win agreement with the woodlanders, who allow part of their forest to be cleared in exchange for cattle.

For a moment, peace returns.

But peace never lasts long. Under moonlight, farmers mount a surprise attack on the herders’ camp, targeting the massive stones being dragged toward the Monument.

Joia and Seft rally defenders. Arrows fly, men fall, and chaos spreads among cattle and warriors alike.

Though outnumbered, the herders repel the assault. At dawn, Joia takes command of the survivors, organizing care for the wounded and burial for the dead.

Despite losses, she pushes on with the hauling of the stones. Her leadership inspires hundreds to continue.

Days later, the herders confront a final ambush by the farmers. Joia orchestrates a daring plan—driving the entire cattle herd into the enemy ranks.

The stampede crushes the attackers, leaving the field strewn with bodies. Among the fallen is Troon, the farmers’ leader.

Joia kills him herself, avenging her brother Han and ending the long feud.

After victory, Joia delivers the last stones to the Monument. As construction resumes, Pia helps rebuild her shattered community, ensuring women have equal voice.

New leaders emerge, and Seft’s engineering genius advances the work. His son Ilian later improves the design with peg-and-socket joints, allowing massive crossbars to be placed atop the standing stones.

Through years of hardship, love, and death, the people unite around one purpose: completing the great circle.

Fifteen winters pass. The Monument stands finished—thirty uprights and thirty crossbars forming a vast stone ring around the original triliths.

Now aged, Ani is carried to witness the first Midsummer Rite within it. As Joia, Dee, and a hundred priestesses chant in harmony, the sun rises perfectly between the stones, filling the circle with light.

The people fall silent, awed by their own creation. The long struggle of families, tribes, and generations has come full circle—out of violence into vision, from scattered clans into a civilization bound by shared purpose.

The sun is up, and all is well.

Characters

Seft

Seft stands at the emotional heart of Circle of Days, representing resilience, self-discovery, and the breaking of generational cycles of violence. Born into a miner’s family ruled by brutality, Seft’s journey from an abused son to a visionary builder mirrors humanity’s evolution from survival to civilization.

His courage surfaces early when he resists his father Cog and brothers Olf and Cam, marking the start of his personal independence. The tenderness he experiences with Neen awakens his sense of worth and longing for love, contrasting sharply with the harshness of his family life.

Despite repeated humiliation and beatings, Seft’s defining trait becomes his creativity—his innovation with flintwork and architecture foreshadows his role in designing the Monument’s structure. Through his compassion, intellect, and endurance, Seft evolves from a victim of violence into a creator of enduring peace and beauty, embodying the transformation of a primitive world into one capable of faith and art.

Neen

Neen is both a symbol of emotional maturity and a quiet force of balance in Circle of Days. Where Seft burns with passion and rebellion, Neen radiates steadiness and empathy.

Her ability to see beyond tribal divisions and personal desires sets her apart as a bridge between old customs and new possibilities. Though she shares deep affection with Seft, she resists immediate attachment, embodying a realism rare for her age and time.

Neen’s family, particularly her mother Ani, influences her to value harmony, community, and emotional intelligence. Her relationship with Seft becomes a crucible in which both characters learn about love not as possession but as mutual understanding.

In the larger tapestry of the story, Neen represents the nurturing aspect of civilization—compassion, connection, and the quiet strength that sustains progress.

Cog

Cog, Seft’s father, personifies the oppressive authority of tradition and the cruelty that sustains patriarchal control. His world is built on dominance, fear, and physical strength—qualities that once ensured survival but now stifle growth.

Cog’s brutality toward Seft and his dismissal of innovation reveal a man trapped by his own limitations. He cannot comprehend change, viewing Seft’s intellect as weakness and his independence as rebellion.

When the community condemns Cog’s violence, it marks a symbolic rejection of an old order. Cog’s eventual isolation underscores the collapse of tyranny and the rise of moral consciousness.

Through him, Circle of Days dramatizes the painful shedding of primitive hierarchies, showing that strength without empathy becomes self-destructive.

Ani

Ani emerges as the moral and spiritual cornerstone of the novel. As Neen and Han’s mother, she anchors her family and community through wisdom, fairness, and compassion.

She represents the dawn of ethical governance—an elder who leads not by fear but by moral authority. Ani’s condemnation of Cog’s brutality reflects her belief that violence has no place in sacred or communal life.

Her leadership during times of crisis—whether in conflicts between herders and farmers or in spiritual ceremonies—embodies the story’s shift from brute survival to collective responsibility. Even in old age, Ani continues to embody faith in human decency, culminating in her witnessing the completed Monument, the ultimate symbol of unity and endurance.

She stands as a matriarchal figure through whom the world of Circle of Days finds its moral compass.

Joia

Joia’s journey is one of self-discovery, identity, and the awakening of leadership. From a curious, introspective girl to a bold commander during war, her growth parallels humanity’s own maturing sense of purpose.

Early on, her uncertainty about desire and difference establishes her as an outsider—a soul questioning established norms. Yet, her intellectual curiosity about numbers, stars, and sacred geometry prefigures her future role in understanding the Monument’s significance.

Joia’s transformation into a leader during the climactic battles marks a turning point: the young girl once unsure of herself becomes the decisive figure who brings order, courage, and unity. By the end, her partnership with Dee merges love, intellect, and faith, positioning her as the inheritor of both emotional and cultural evolution in Circle of Days.

Pia

Pia’s character embodies endurance through trauma and the quiet strength of ordinary survival. Her journey from a frightened girl witnessing brutal deaths to a pragmatic, resilient mother reveals a different kind of heroism—one rooted in endurance rather than glory.

Pia’s suffering under Stam’s domination and her later role in rebuilding community life show her capacity to heal, nurture, and lead through empathy. Unlike Seft or Joia, her transformation is domestic and moral, not monumental.

Yet, her story adds depth to the novel’s exploration of justice, as she bears witness to both cruelty and the possibility of renewal. Pia’s grief and perseverance symbolize the unacknowledged backbone of civilization: the endurance of women who hold life together amid loss and conflict.

Troon

Troon represents political ambition and the dark side of progress—the will to dominate masked as leadership. As the Big Man of the farmers, he embodies greed, patriarchy, and arrogance.

His belief in land ownership as power drives the central conflicts between farmers and herders. Through Troon, Circle of Days explores how societal evolution can regress when guided by pride rather than cooperation.

His downfall—crushed by the very forces he sought to control—becomes poetic justice, symbolizing the destruction of tyranny by collective will. Troon’s brutality and eventual death mark the end of an era defined by coercion, giving way to a more just social order.

Stam

Stam stands as one of the novel’s most disturbing figures—a personification of violence unleashed when social and moral structures collapse. His murder of Han and Fell, his enslavement of Pia, and his cowardice all reveal the dangers of unchecked power and the fragility of moral restraint.

Stam’s death at the hands of the woodlanders restores cosmic balance, as justice in Circle of Days is often portrayed as divine rather than human. His arc exposes the thin line between man and beast, reminding readers that the evolution of society depends on curbing impulses of cruelty and vengeance.

Stam’s destruction thus serves as a necessary purging of darkness to make room for renewal.

Bez

Bez, the woodlander hunter, embodies a stoic form of justice rooted in community ethics and natural balance. Unlike the farmers or herders who vie for dominance, Bez represents an older harmony with the land and its spiritual laws.

His decision to avenge Fell and Han is not driven by rage but by the belief in restoring equilibrium. Through his interactions with Pia and Ani, Bez bridges the different tribes, helping shape alliances that prevent further war.

In the later parts of the story, his cooperation with Seft and Ani in crafting peaceful solutions underscores his transformation from avenger to peacemaker, showing that wisdom, not vengeance, sustains civilization.

Dee

Dee’s presence in Circle of Days enriches the novel’s exploration of love, identity, and devotion. Her bond with Joia transcends traditional boundaries, offering a vision of companionship based on equality and shared purpose.

Dee’s independence and moral clarity challenge conventional expectations of womanhood in their world. She fights in battles, nurtures others, and ultimately chooses the priestesshood not as an escape from love but as a way to integrate it into spiritual life.

Her decision to remain true to herself, even when it means separation, reflects the novel’s deeper theme of harmony between individual and communal growth. Dee’s relationship with Joia thus becomes a metaphor for the synthesis of love and faith—the twin pillars of the new age their world is entering.

Themes

Family and Generational Conflict

The heart of Circle of Days is charged with the tension between fathers and sons, authority and rebellion. Seft’s relationship with his father, Cog, stands as the clearest embodiment of this conflict.

Cog’s worldview is rooted in brute survival and patriarchal control, where obedience is prized above all else. Seft, however, begins to sense the possibility of a different kind of life—one shaped by choice, kindness, and craft.

The violence between them represents more than familial cruelty; it is the friction of a changing world. Seft’s defiance, culminating in his physical and emotional break from Cog, symbolizes a generational shift from coercion to creativity, from dominance to collaboration.

This theme expands across other families too: Ani’s nurturing leadership contrasts with Cog’s tyranny, and Joia’s coming of age reflects a gentler, evolving understanding of family bonds. By the end, family is no longer defined by blood or subjugation, but by mutual respect and shared purpose.

The completion of the Monument, built by cooperative effort and intergenerational knowledge, serves as a metaphorical reconciliation of what family could become—no longer a site of inherited brutality but of continuity and growth through compassion.

Love, Desire, and Emotional Awakening

Love in Circle of Days is portrayed not as idealized romance but as a force of transformation and revelation. Seft and Neen’s relationship begins with physical longing but matures into an exploration of vulnerability and independence.

Their connection awakens Seft to the possibility of tenderness in a world hardened by labor and violence. Yet, Neen’s refusal to bind herself immediately to him shows love as a process of mutual recognition, not possession.

Alongside this, Joia’s sexual awakening is handled with profound sensitivity—her confusion, her feelings for Kae, and her eventual self-acceptance reveal the spectrum of human desire. Follett situates love as both a personal and social disruptor, a means through which individuals challenge imposed roles and expectations.

It forces self-examination, leading characters to question not only who they love but what love itself should mean within their evolving communities. By the novel’s end, the union of Joia and Dee within the priestesshood symbolizes a love that transcends gender and convention, affirming emotional honesty as sacred and revolutionary.

Oppression, Power, and Justice

Throughout Circle of Days, power manifests in raw, physical terms—through patriarchs, warlords, and the control of resources—but Follett uses these displays to critique the fragility of domination. Cog, Troon, and Shen represent different shades of authoritarianism: the domestic tyrant, the political despot, and the opportunist.

Each uses fear and violence to maintain control, yet all are undone by collective resistance and moral outrage. Ani’s public condemnation of Cog marks a pivotal reordering of justice—from private vengeance to communal accountability.

Similarly, Pia’s suffering under Stam and Troon’s regime exposes how systemic brutality persists even in small societies. Her eventual collaboration with Bez and the woodlanders to restore balance through revenge reflects the primal human need for reparation but also the danger of retribution becoming cyclical.

By contrasting personal vengeance with the communal vision of the Monument, Follett suggests that justice evolves from survival instinct toward the creation of enduring moral structures—structures that, like the stones themselves, outlast violence.

Innovation and the Human Drive to Create

Creation—both literal and symbolic—is central to the novel’s movement from primal survival to civilization. Seft’s ingenuity with flintwork and architectural design embodies humanity’s first stirrings of engineering thought.

His peg-and-socket mechanism for the Monument marks a leap from brute labor to intentional design, positioning human creativity as a redemptive force. The building of the Monument transforms from a tribal task into a collective expression of purpose, blending practicality with spiritual significance.

Each stone raised is not just a triumph of muscle but of imagination—the belief that something lasting can be built from transient lives. The collaborative nature of the construction, drawing farmers, herders, and woodlanders together, symbolizes how innovation bridges divisions.

The shift from violence to architecture, from destruction to creation, encapsulates Follett’s larger meditation on progress: that civilization begins when human hands, instead of wielding weapons, begin to shape enduring forms from stone and vision.

Gender, Leadership, and Social Transformation

Circle of Days consistently redefines leadership through its women. Ani, Joia, Pia, and Dee embody strength that does not rely on dominance but on empathy, reason, and endurance.

Ani’s diplomacy averts wars that men’s pride might have ignited; Joia’s command during the monument’s final stages transforms her from a curious girl into a leader capable of uniting hundreds. The narrative tracks a subtle but radical evolution in gender roles—from women seen as adjuncts to men’s work to central figures in community survival and moral reasoning.

Even in love, women maintain autonomy; Neen’s decisions underscore the right to self-determination, while Joia and Dee’s relationship broadens the social understanding of partnership. The rise of Duff as a leader who promises equality for women cements this transformation at the societal level.

By the conclusion, the completion of the Monument under women’s spiritual and organizational guidance stands as an emblem of a world where authority is no longer bound to gender but earned through wisdom and compassion.

Community, Unity, and the Birth of Civilization

At its core, Circle of Days charts humanity’s transition from fragmented tribes to a sense of shared identity. Early divisions—between miners, herders, farmers, and woodlanders—mirror the chaos of unconnected survival.

Follett’s story gradually threads these groups into cooperation, first through necessity, later through vision. The Monument becomes the physical and moral center of this unity, a structure that embodies the merging of cultures, beliefs, and labor.

The final Midsummer Rite, with all peoples gathered in harmony, affirms civilization not as an inheritance but as an achievement born of shared struggle. This theme reaches its height in the juxtaposition of war and construction: while violence threatens to erase progress, the community’s collective will to build asserts that meaning is found not in conquest but in continuity.

The closing image of dawn illuminating the completed circle signifies more than an architectural triumph—it marks the dawn of humanity’s moral awakening, where cooperation replaces conflict, and the cycle of days becomes a circle of shared purpose.