Clown Town Summary, Characters and Themes

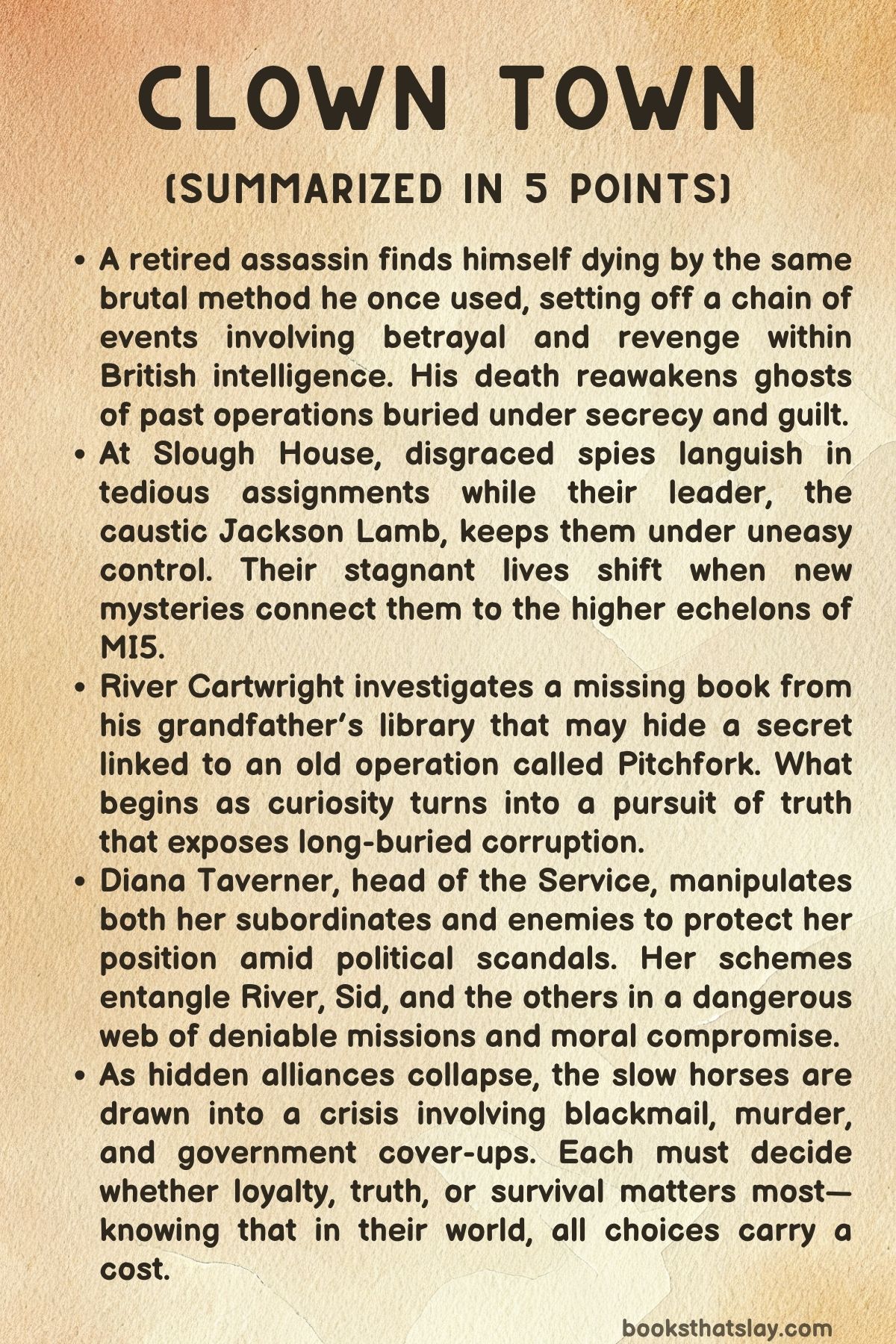

Clown Town by Mick Herron is a tense, darkly comic spy thriller that continues Herron’s acclaimed exploration of British intelligence’s most dysfunctional outpost, Slough House. The novel opens with a chilling execution that mirrors the past crimes of its victim, then expands into a web of deceit, revenge, and bureaucratic rot.

Herron paints an unflinching portrait of aging spies, political manipulation, and moral decay in the shadows of government. Amid broken loyalties and decaying institutions, a group of washed-up operatives—known as “slow horses”—find themselves caught between the ruthless ambitions of their superiors and the ghosts of operations long buried. It’s the 9th book in the Slough House series by the author.

Summary

A retired state assassin living under protection in northern England awakens one morning to find himself tied up, his head pinned beneath a Land Rover tyre—the same execution method he once used on others. Initially believing it to be a nightmare, he soon realizes it is real when his killer repeats his own final words, “Any final observations?

” The man dies as he once killed, and his death sets in motion a chain of consequences that will ripple through the intelligence community.

In London, Slough House—an offsite dumping ground for disgraced MI5 operatives—slinks unnoticed between a shuttered Chinese restaurant and a dingy newsagent. Inside, its exiled agents toil in pointless administrative work, buried under dust, gloom, and resentment.

Catherine Standish, Shirley Dander, Roddy Ho, Lech Wicinski, Ash Khan, and Louisa Guy each battle their personal demons while enduring the harsh leadership of Jackson Lamb, their brilliant but appalling superior. Catherine tries to rein in the volatile Shirley, who refuses to apologize for disrupting rehab.

Roddy obsesses over trivial vanity, Lech hides behind menial database checks, and Ash fields nagging calls from her mother as she sifts through meaningless student records.

Meanwhile, Diana Taverner—the powerful yet embattled head of MI5—struggles with political pressure and blackmail from her ally-turned-threat, Peter Judd. She receives an anonymous recording tied to a covert operation called Pitchfork and discreetly begins investigating old files, including those of River Cartwright, one of Lamb’s agents.

River, recovering from near-death exposure to nerve agents, lives with his former colleague Sid Baker. When an Oxford researcher named Erin Grey mentions a mysterious missing book from his late grandfather’s library, River is drawn into a personal mystery.

The book, captured on video but nonexistent in reality, may conceal something far more significant than its title suggests.

At Oxford, River meets Erin and her mentor, Charles Stamoran, who claims the missing volume—a disguised safe—contained only embarrassing pornography belonging to River’s grandfather, the legendary spymaster David Cartwright. River doubts this explanation, suspecting the safe once held evidence of a buried secret.

Elsewhere, Taverner meets with Lamb to vent about bureaucratic complaints and reveal her decision to block River’s return to duty. Lamb appears indifferent, though his silence conceals interest.

In another corner of England, four aging ex-operatives—Al Hawke, Avril Potts, Daisy Wessex, and CC (Charles Cornell Stamoran, the same man who misled River)—gather in a decaying safehouse. Years ago, they ran Operation Pitchfork, handling an IRA enforcer turned British asset who continued murdering under their supervision.

When the operation collapsed, the Service erased it and ruined their careers. CC reveals that David Cartwright recorded the final meeting about Pitchfork’s closure, and he now possesses that tape.

To force restitution, CC has already leaked part of it to Taverner. His team fears imprisonment, but he insists it’s too late to turn back.

Taverner soon enlists Sid Baker to act as her go-between, offering River’s reinstatement in exchange for an unspecified errand. Sid reluctantly delivers a cash envelope and burner phone to CC but is taken hostage by the Brains Trust—the ex-agents’ nickname for themselves—when Daisy mistakes her for a threat.

Though CC later abandons her at a service station, Sid manages to contact the slow horses, who scramble to understand Taverner’s endgame. Lamb deduces that Taverner is exploiting the Brains Trust as disposable assets for a secret mission—possibly an assassination.

As Taverner meets CC on Calthorpe Street, she confronts him with her knowledge: the Brains Trust murdered Pitchfork themselves, crushing his skull with a Land Rover to end his atrocities. Only David Cartwright ever discovered this truth.

She threatens exposure to coerce CC into serving her once more. Lamb’s team, connecting the dots, suspects she’s sending CC to eliminate Peter Judd, a political liability with leverage over her.

River and Sid rush to intervene as the slow horses mobilize chaotically toward the target site—a derelict nightclub called Nob-Nobs.

Inside the club, chaos unfolds. Judd arrives for a covert meeting, CC hesitates with a gun, and the slow horses burst in from multiple directions.

Misunderstandings erupt, shots are fired, and lives are lost. When the smoke clears, Louisa Guy lies gravely wounded, and the cover-up begins.

Days later, at Slough House, the surviving agents gather under Lamb’s sardonic supervision. He explains that Taverner’s special unit is already spinning the story to absolve the Service of blame.

She’s desperate to bury the evidence, fearing Judd might retaliate by exposing her complicity in illegal operations. Lamb crafts his own plan—a supposed “diplomatic” meeting—to bring Taverner and Judd together.

His subordinates suspect it’s a prelude to murder.

Roddy disables surveillance cameras across Notting Hill, unaware that his handiwork will cloak something darker. At the Park, Taverner consolidates power by blackmailing the Prime Minister with an old recording linking him to IRA dealings.

Her political survival seems secure until Judd, shaken but alive, begins plotting revenge. He knows she hired assassins through Chinese intermediaries and plans to expose her corruption.

Meanwhile, Louisa awakens in the hospital, barely surviving her injuries. River, haunted by guilt, obeys Lamb’s orders to chauffeur Judd to Taverner’s home for the “meeting.” Roddy’s camera sabotage partially fails, forcing him to destroy the remaining CCTV manually, resulting in chaos and injury. As he bleeds and flees through the city, Lamb’s scheme unfolds.

Inside Taverner’s house, Judd encounters Lamb alone. Their conversation veers between mockery and menace.

Judd offers Lamb wealth and retirement to keep quiet, but Lamb has already made his decision. When Judd boasts of future manipulations, Lamb shoots him once through the chest, places the gun in Taverner’s safe, and departs unseen.

Within hours, the police swarm her home, finding the corpse and the incriminating weapon.

Taverner, outwardly calm, smokes in her garden while holding a microcassette—the same device that once secured her dominance. The Prime Minister and his aides scramble to contain the scandal, debating how much of the truth to suppress.

At Slough House, Lamb resumes drinking as Catherine Standish confronts him. She knows he orchestrated Judd’s death but receives only his evasive reply: “Spies lie.” The fallout, she warns, will destroy them all. Lamb, indifferent, jokes that he’s merely spoiled a few evenings.

Elsewhere, Avril Potts waits outside the battered Oxford safehouse, wondering if her fugitive friends have survived. Across London, the wreckage of deceit settles: Louisa lives, Judd is dead, Taverner’s future uncertain, and Lamb—smelling of smoke and whisky—sits alone in his decrepit office, unmoved and undefeated.

In Clown Town, justice, revenge, and survival blur into one, leaving the living to wonder whether any of them ever truly escaped the shadows.

Characters

Jackson Lamb

Jackson Lamb stands as the caustic yet commanding leader of Slough House, the derelict outpost for MI5’s failed agents in Clown Town. Lamb’s exterior—slovenly, vulgar, and seemingly indifferent—conceals one of the sharpest minds in the intelligence world.

His deep cynicism toward bureaucratic authority, especially toward figures like Diana Taverner, stems from years of witnessing corruption and manipulation at the highest levels. Lamb’s methods are crude but effective, and his loyalty to his team, though hidden behind insults and manipulation, is undeniable.

Beneath his disdain lies an old-school spy’s moral code: unsentimental, ruthless when necessary, but rooted in a belief that the Service should protect its own. His execution of Peter Judd in the end—done with chilling pragmatism—cements his role as both executioner and protector, ensuring the survival of his “slow horses” by turning the game back on those who play it.

River Cartwright

River embodies the tragic idealist of Clown Town—a capable field agent exiled to Slough House due to one catastrophic mistake. Haunted by his family legacy, particularly the towering shadow of his grandfather, David Cartwright, River is torn between loyalty, guilt, and the need for redemption.

His physical recovery from nerve agent exposure mirrors his psychological battle: an attempt to reclaim identity and purpose in a profession that dehumanizes its own. River’s relationship with Sid Baker reflects his yearning for connection amid the cynicism of espionage.

His pursuit of the missing book, The Secret Voices, leads him deeper into the labyrinth of hidden truths surrounding his grandfather and Operation Pitchfork. Ultimately, River represents the decaying moral conscience of British intelligence—someone who still wants to believe in integrity even as he’s surrounded by betrayal.

Diana Taverner

Diana Taverner, the formidable First Desk of MI5, is the embodiment of cold, political intelligence. Her ambition and survival instincts drive the narrative’s most dangerous manipulations.

In Clown Town, Taverner moves beyond mere schemer—she becomes an architect of moral decay within the Service. Every alliance she forges, from manipulating CC Stamoran to sacrificing Judd, serves to consolidate her control.

Yet Herron crafts her not as a villain but as a reflection of systemic rot: a woman fighting to maintain order in a system that rewards deceit. Her calculated composure collapses only briefly when she realizes how Lamb outplays her in the end.

Taverner’s calm acceptance of Judd’s death and her own impending downfall captures the tragic irony of her character—she’s both a victim and a creator of the machine she serves.

Louisa Guy

Louisa Guy brings quiet strength and tragedy to the narrative. Once a capable field agent, she carries the emotional scars of losing her partner and the bitterness of being exiled to Slough House.

Throughout Clown Town, Louisa’s internal conflict revolves around duty versus escape—Devon Welles’ job offer tempts her with normalcy, but her loyalty to Lamb’s dysfunctional team ultimately prevails. Her near-fatal injury during the final act is symbolic of the constant cost paid by those who remain loyal to a decaying institution.

Louisa’s awakening in the hospital signals resilience amid ruin—a survivor’s return in a world that consumes its best people.

Sid Baker

Sid’s reappearance after her presumed death in earlier Slough House stories adds layers of vulnerability and tension to Clown Town. Her deep connection to River anchors much of the emotional core of the book.

Intelligent, loyal, and morally upright, Sid operates in sharp contrast to the duplicity surrounding her. Used as a pawn by Taverner and later caught in the Brains Trust’s desperate maneuvering, Sid becomes the moral compass—an outsider witnessing the rot from within.

Her attempts to protect River, even when manipulated, demonstrate quiet heroism. Through Sid, Herron explores how integrity survives in a profession designed to extinguish it.

Catherine Standish

Catherine Standish is the beating heart of Slough House—its conscience, caretaker, and chronic sufferer. A recovering alcoholic, she functions as the mother figure to the lost spies around her.

Her compassion contrasts sharply with Lamb’s cynicism, yet she understands him better than anyone. In Clown Town, Catherine continues to endure with quiet strength, holding the broken team together even as more of them die or disappear.

Her final confrontation with Lamb, when she accuses him of orchestrating Judd’s death, exposes her moral clarity. Though weary and wounded, she remains the last custodian of decency in a world built on lies.

Roddy Ho

Roddy Ho provides comic relief and tragic absurdity in equal measure. A self-proclaimed cyber-genius with delusions of grandeur, Roddy’s arrogance masks insecurity and loneliness.

His technological incompetence during critical moments, especially his disastrous attempt to disable CCTV, highlights the absurdity of the “slow horses” while revealing a subtle humanity beneath his vanity. Despite ridicule, Roddy’s survival amid chaos underscores one of Herron’s recurring themes: that mediocrity, stupidity, and blind luck often outlast skill in espionage.

Lech Wicinski

Lech Wicinski’s trauma—both physical and psychological—renders him one of the most quietly tragic figures in Clown Town. Once a capable agent, his disfigurement and paranoia isolate him from his colleagues.

Yet his methodical work, even when meaningless, reflects a yearning for redemption through order. Lech’s cynicism mirrors Lamb’s but lacks Lamb’s control; his bitterness stems from being discarded by the system he served faithfully.

Through Lech, Herron portrays the long-term human wreckage of intelligence work—the bodies and minds left behind when missions end.

Shirley Dander

Shirley Dander is chaotic, volatile, and painfully self-destructive. Her substance abuse and rebellious streak often make her the comic foil of Slough House, yet Clown Town reveals her as another casualty of institutional neglect.

Beneath her fury lies a desperate need to prove herself worthy of the Service that rejected her. Her interactions with Catherine show flashes of vulnerability—an unspoken desire for guidance that she can’t accept.

Shirley’s aggression and wit conceal fear: fear of irrelevance, failure, and emotional exposure.

CC (Charles Cornell Stamoran)

CC Stamoran, once a respected operative, now the disgraced leader of the Brains Trust, represents the haunting consequences of secrecy. His attempt to blackmail MI5 using the Pitchfork recordings is both an act of vengeance and despair.

CC’s complexity lies in his contradictions—he’s intelligent yet reckless, manipulative yet nostalgic for the idealism of his youth. His decision to reengage with Taverner seals his doom, but it also exposes the cycle of betrayal that defines the Service.

In CC’s downfall, Herron captures the tragedy of those who cannot let go of the spy world’s illusions of control.

Avril Potts, Al Hawke, and Daisy Wessex

These three former agents form the fragmented remnants of a once-cohesive unit, each carrying moral scars from the Pitchfork operation. Avril, pragmatic and weary, is the group’s conscience, torn between self-preservation and guilt.

Al, sardonic and broken, represents the nihilistic side of espionage—the acceptance that there is no redemption. Daisy, mentally unstable and haunted by violence, embodies the psychological toll of secrets.

Together, they illustrate the human debris of intelligence work: people discarded once their usefulness ends, clinging to each other out of shared shame and fear.

Peter Judd

Peter Judd, the corrupt politician whose ambition rivals Taverner’s, epitomizes the merging of politics and espionage. His charisma and cynicism make him both comic and sinister.

Judd’s downfall—executed by Lamb—is poetic justice: a man who weaponized secrets undone by one. His interactions with River reveal the arrogance of power that sees intelligence as a tool rather than a duty.

Through Judd, Herron satirizes political opportunism and moral decay in modern governance.

Themes

Guilt and Retribution

The moral architecture of Clown Town is built around the inescapability of guilt and the cyclical nature of retribution. Every act of violence, deception, or betrayal within the intelligence community creates an echo that eventually returns to punish its originator.

The book begins and ends with this motif—the assassin who once executed traitors by pinning their heads under a Land Rover wheel meets the same fate himself, a grim symmetry that sets the tone for the narrative. Across the story, guilt takes many forms: personal, institutional, and historical.

Characters such as River Cartwright, Diana Taverner, and the aging Brains Trust carry the psychological residue of operations long buried but never forgotten. Their lives are shaped by an unspoken moral debt, where past sins manifest as paranoia, ruined careers, or self-destruction.

Retribution here is not divine but procedural, a natural consequence of lives spent manipulating and disposing of others. Mick Herron shows that within the espionage world, guilt is not absolved but recycled—transferred from one agent to another, from one decade to the next.

Even Lamb’s sardonic pragmatism conceals his understanding that every lie and death will eventually surface, demanding payment. The novel therefore transforms guilt into a system of justice that functions independently of conscience or authority, suggesting that within this bureaucratic world of spies, the only true reckoning is the one no one can escape.

Institutional Decay and Bureaucratic Corruption

The bleak environment of Slough House embodies the erosion of moral and operational integrity within British intelligence. The building itself—filthy, cluttered, and neglected—serves as a visual metaphor for an organization rotting from within.

Herron’s portrayal of bureaucracy reveals how systems designed to protect the state become mechanisms of suppression and self-preservation. Slough House’s inhabitants are not merely incompetent; they are casualties of a hierarchy that discards its servants once they become inconvenient.

Diana Taverner’s manipulations, political alliances, and cover-ups show how corruption evolves into standard procedure. Each decision is shaped not by ideology or patriotism but by survival—personal, institutional, and political.

Paperwork replaces purpose, and the intelligence service, once imagined as a noble guardian, has become a paranoid network of favors, files, and lies. The decay is moral as much as structural: even those who see the corruption, like Lamb or River, are complicit in maintaining it, knowing that rebellion would destroy them.

Through this theme, Clown Town captures the tragedy of modern espionage—an enterprise that once thrived on clarity of purpose now sustained only by habit and hypocrisy. The decrepit walls of Slough House are thus not only physical ruins but the visible remains of an empire of deceit.

The Weight of the Past

The past functions as an omnipresent force in Clown Town, dictating every character’s choices and sealing their destinies. The operation known as Pitchfork represents this weight most vividly: a forgotten atrocity from Northern Ireland that returns to haunt both the perpetrators and their successors.

Herron uses the resurfacing of the recording and the missing book to illustrate how the past cannot be neatly archived—it leaks into the present, contaminating it. For River, the mystery surrounding his grandfather’s secret library and the missing volume becomes a confrontation with familial and national legacies.

His search for truth is less about espionage and more about inheritance—understanding what moral compromises are passed down through generations. Similarly, Taverner’s political maneuverings are driven by fear of exposure, proof that history remains an active predator.

Even the Brains Trust, whose attempt to blackmail the Service stems from old betrayals, demonstrates that time does not erode guilt but amplifies it. Herron’s narrative insists that the past, once weaponized, becomes self-perpetuating: lies beget more lies, cover-ups lead to new crimes, and the ghosts of forgotten operations continue to dictate the living.

The result is a portrait of a society trapped in its own history, unable to progress because it cannot bear to acknowledge the truth.

Loyalty, Betrayal, and Survival

In Clown Town, loyalty is portrayed not as virtue but as currency—a negotiable bond traded in moments of convenience or desperation. Agents swear allegiance to the Service, yet every relationship is defined by conditional trust.

Diana Taverner betrays colleagues, subordinates, and the very institution she serves, all to protect her position. Jackson Lamb, though outwardly cynical and insubordinate, demonstrates a paradoxical loyalty to his team; he shields them through deceit and manipulation, suggesting that betrayal and loyalty are merely two sides of the same instinct for survival.

The Brains Trust’s collapse under mutual suspicion further highlights this moral corrosion. Even River’s devotion to Sid and his loyalty to the memory of his grandfather are tested against the relentless pragmatism of espionage life.

In this world, betrayal is not shocking—it is routine. What matters is how one survives it.

Herron’s treatment of this theme strips away the romanticism often attached to spy fiction; espionage here is not a battle of ideologies but a desperate negotiation between competing betrayals. Loyalty, when it appears genuine, is simply the absence of a better option.

The novel ultimately argues that survival, not duty, governs every moral choice, and those who mistake loyalty for honor are the ones most easily destroyed.

Identity and Self-Deception

Every operative in Clown Town lives behind masks, both literal and psychological, creating a web of self-deception that defines their existence. The spies of Slough House have been shaped by failure, yet they continue to pretend their work matters, sustaining the illusion of purpose in an institution that has forgotten them.

River Cartwright’s journey illustrates this tension between self-perception and reality. His need to believe in his competence and integrity clashes with his growing recognition that the Service has long abandoned its ideals.

Similarly, Diana Taverner’s projection of control conceals her fragility; she manipulates others to avoid confronting her own moral collapse. Jackson Lamb’s grotesque indifference—his filth, insults, and vices—acts as a mask concealing a keen intelligence and a buried moral compass.

Herron portrays identity as a costume forced upon individuals by the systems they inhabit. To survive, they must continually lie—to enemies, allies, and themselves.

Yet self-deception comes with a cost: the slow erosion of the soul. In this sense, Clown Town becomes a study of what happens when individuals live too long within false identities—when the lies that protect them also destroy what remains of their humanity.