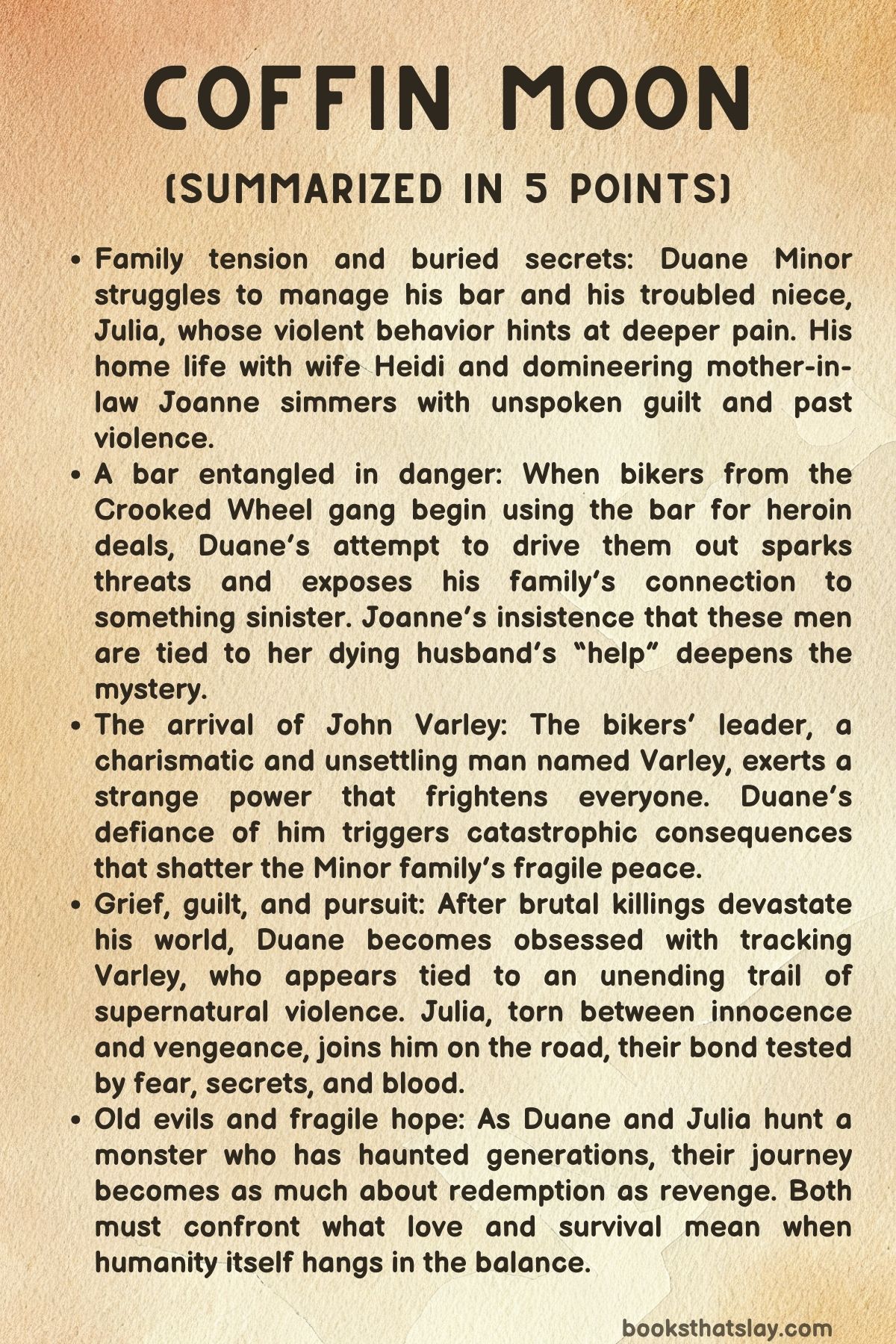

Coffin Moon Summary, Characters and Themes

Coffin Moon by Keith Rosson is a dark, character-driven novel that blends crime, horror, and tragedy into a story about love, loss, and the monsters—both human and otherwise—that inhabit ordinary lives. It follows Duane Minor, a weary Vietnam veteran turned bar owner, and his niece Julia, a troubled girl shaped by violence.

When their family is destroyed by a supernatural killer, the two are drawn into a relentless cycle of revenge and survival that spans years and crosses into the realm of the undead. Through their journey, Rosson explores grief, morality, and the haunting cost of vengeance.

Summary

Duane Minor runs the Last Call, a working-class bar in Portland, while raising his teenage niece, Julia, with his wife, Heidi. Julia has a history of fighting and trauma from her violent childhood, where she witnessed her mother shoot her abusive stepfather.

Despite the family’s attempts at normalcy, Julia’s anger and guilt strain her relationship with Duane and Heidi. Meanwhile, tension builds in the bar when members of a biker gang called the Crooked Wheel start frequenting the place.

Their intimidating behavior unsettles Duane, who suspects they’re dealing drugs.

When he confronts them, he discovers his mother-in-law and bar owner, Joanne, has secretly allowed them to operate there. Her reason shocks him—her husband Ed, Heidi’s father, is dying of brain cancer, and the bikers supposedly work for someone who can help.

Duane assumes she means financial help, but her fear and insistence that he not interfere suggest something stranger. When Duane defies her and drives the bikers out violently, she warns him he has ruined everything and threatens to expose a dark secret from his past—an incident of lethal violence that only the two of them know.

Soon after, Duane’s world collapses. One night, while he’s working a shift, Julia calls from a sleepover, frightened and wanting to come home.

When he goes upstairs to fetch Heidi, he finds her brutally dismembered. Hours later, police inform him that Joanne and Ed have also been slaughtered.

The murders are grotesque—limbs torn apart, bodies shredded. The police suspect the Crooked Wheel, but the photos Duane shows them—Polaroids of the bikers and their leader John Varley—reveal something eerie: Varley’s face is blurred and empty, as if the camera couldn’t capture him.

Grief and paranoia consume Duane. He checks into a motel with Julia, now the only family he has left.

They cling to each other, traumatized and fearful. The police, led by Detective Scoggins, suspect Duane might be involved in drug dealings gone wrong.

Yet as new bodies surface, torn apart like the others, Scoggins begins to consider the impossible: that Varley may not be human. He reveals that a John Varley was once arrested in 1931 for similar mutilation murders but vanished from custody.

The killings stopped for decades—until now.

When Julia overhears, she becomes convinced Varley is something supernatural. As Duane sinks into drinking and despair, Julia decides to take action.

She sneaks away, wandering the snowy streets in search of clues. Her reckless quest nearly destroys her, but Duane finds her before anything happens.

Tearfully reunited, they promise to face what’s coming together.

The narrative jumps ahead eighteen months. Duane and Julia have become fugitives, bonded by blood and horror.

Julia has been turned into a vampire—a choice born of necessity when she saved Duane’s life during their hunt for Varley. Now they live a nomadic existence, moving from town to town, hiding by day, hunting by night.

Duane provides her with blood from his own veins, keeping her fed while suppressing his own hunger and guilt.

Flashbacks reveal Julia’s earlier life: her mother’s desperate act of killing her abusive partner, the separation from her brother Kevin, and her eventual move to Oregon. Despite the stability Heidi and Duane offered, the shadows of her past never left her.

Now, as a vampire, she carries those scars into a new kind of darkness.

Together, Duane and Julia track other vampires, seeking any lead on Varley. In upstate New York, they find a dying vampire called Cobweb Jim, who trades information for Duane’s blood.

He tells them of a man in Fargo who forges silver bullets—the only weapon that can kill Varley. Duane buys six of them at a steep price, believing they hold his only chance for redemption.

During a tense call with Detective Scoggins, Duane learns that Varley has been linked to violent deaths across the country. Scoggins pleads with him to surrender Julia to safety, but Duane refuses, saying they’ve come too far.

Later, Duane confesses to Julia that years earlier, drunk and broken after Vietnam, he nearly beat two burglars to death and that Joanne helped cover it up. He fears that to defeat Varley, he’ll have to become that man again—the violent self he’s tried to bury.

Parallel to this, Varley’s story unfolds. Once a hired killer in early 1900s Seattle, he was turned into a vampire by a monstrous creature who became his Maker.

In the present, he hunts across America, wounded by a silver bullet and consumed by revenge after Julia killed his lover. Desperate, he captures a young man, performs a ritual, and summons his Maker—now a charred, dying horror.

When the creature mocks him, Varley kills and consumes him, absorbing his power and cleansing the silver from his body. Newly strengthened, he senses Julia’s presence and heads west to Portland for a final confrontation.

In Portland, Duane and Julia arrive at Lone Fir Cemetery, where Heidi and her parents are buried. Duane visits their graves, haunted by memories.

Detective Scoggins appears and arrests him, but before they can leave, Varley materializes and slashes Scoggins’s throat. A brutal fight follows among the gravestones.

Duane, now partly vampiric, struggles to hold his own. Varley overpowers him, reveling in cruelty and confessing to Heidi’s tormented death.

Julia arrives, armed with the silver bullets. The weapon burns her hands, but she fires again and again, tearing through Varley’s face and arm.

Mortally wounded, he flees into an abandoned building, trying to feed on a homeless man, but the silver-tainted blood poisons him. Duane tracks him down, and the two face each other amid the ruins—hunter and hunted, both damned.

When Julia appears, she ends it with a final shot to Varley’s skull. His body collapses, lifeless at last.

Afterward, Julia leaves the last silver bullet with Duane, telling him it’s his choice—to live or die. Outside, she feeds on a wounded man to keep them alive, transforming him so he will survive.

Duane, now a vampire himself, drives aimlessly through the dark city, torn between self-destruction and the faint hope of a future. He returns to the old bar, now renamed, and finds Heidi’s bloodstained manuscript and the old Polaroids.

He pours a beer he can’t drink and begins to read, caught between memory and survival.

In the closing pages, Julia walks alone through Portland, remembering a night long ago when she and Heidi counted coins above the bar. She reaches a place called the Children’s Museum, where another vampire named Adeline waits.

Julia knocks, ready to pay the debt owed for her turning and vengeance. She plans one day to visit her imprisoned mother and estranged brother—to give them a choice, just as she was given one.

The door opens into darkness, and she steps forward, unafraid, into whatever comes next.

Characters

Duane Minor

Duane Minor stands at the emotional core of Coffin Moon, embodying a deeply flawed yet redemptive masculinity haunted by violence and guilt. A Vietnam veteran and bar owner, Duane’s life is governed by the tension between his instinct to protect and his propensity for destruction.

His love for his wife, Heidi, and adopted niece, Julia, is genuine, but it is constantly undermined by the shadows of his past—his alcoholism, his suppressed rage, and the dark secret of the men he once nearly beat to death. Rosson crafts Duane as a man whose life is an uneasy balance between decency and savagery, love and ruin.

His descent into grief following Heidi’s murder and his eventual transformation into a vampire mark the collapse of his humanity, yet even as a monster, he retains a stubborn moral compass. His devotion to Julia transforms from guardianship to partnership, and ultimately to a tragic, almost holy pact of survival and vengeance.

Duane is both protector and penitent, a man who becomes what he most fears in order to safeguard what he loves most.

Julia Shaw

Julia Shaw’s journey through Coffin Moon is one of trauma, resilience, and transformation. From the opening scenes, she is marked by anger and alienation—a girl forged in abuse and abandonment.

Her violent outbursts at school and her emotional walls are the residue of years spent under Ray Sikes’s brutality and the violent end her mother brought to that nightmare. When Julia becomes part of Duane and Heidi’s family, she begins to heal, finding fleeting stability and affection.

Yet, the horror that shatters her new life—Heidi’s murder, the supernatural eruption embodied by John Varley—propels her into an existence defined by vengeance. Her transformation into a vampire crystallizes her internal struggle: she becomes the very thing she once feared, yet she uses that monstrosity as a means of justice and survival.

Julia’s maturity through the story reflects both empowerment and loss—she grows sharper, colder, yet paradoxically more compassionate toward Duane. By the novel’s end, she emerges as an almost mythic figure, shaped by death but still seeking connection and purpose.

Heidi Minor

Heidi Minor represents the fragile heart of domesticity and creativity within the novel’s grim world. A writer working on her manuscript, The Hollow, Heidi is compassionate, perceptive, and quietly strong, serving as both emotional and moral anchor for Duane and Julia.

Her understanding of Julia’s trauma and her patience with Duane’s volatility ground the family in tenderness. Her murder is not only the narrative’s emotional rupture but also the symbolic end of innocence and normalcy.

Through Heidi, Rosson paints the tragedy of ordinary goodness—how love, art, and empathy can be extinguished by forces of violence and darkness. Even after her death, she remains present through memory, manuscript, and the “three good things” ritual, which becomes Duane and Julia’s way of holding onto her spirit.

Joanne and Ed

Joanne and Ed, Heidi’s parents, form the generational foundation of the Minor family. Joanne, hard-edged and commanding, is both protector and manipulator.

Her complicated moral compass—willing to deal with drug-running bikers and threaten Duane to save her dying husband—reveals the moral compromises people make for love. Her fierce loyalty to family is inseparable from her ruthlessness, and her dynamic with Duane oscillates between maternal concern and condemnation.

Ed, gentle and dying, is the quiet soul of the family, his decline setting much of the tragedy in motion. Together, they embody the old world of labor and sacrifice, undone by secrets and supernatural intrusion.

Their deaths deepen the generational curse that seems to haunt the Minors, linking domestic decay with cosmic horror.

John Varley

John Varley is the novel’s central antagonist and its most enigmatic creation—a figure straddling crime, myth, and nightmare. Once human, he is a relic of violence spanning more than a century, a vampire whose charisma masks absolute corruption.

Varley embodies hunger in all its forms: for blood, power, companionship, and control. His inability to appear clearly in photographs mirrors his metaphysical elusiveness—he is both tangible and spectral, ancient yet constantly reborn through carnage.

Varley’s cruelty is not mere sadism but an assertion of dominance over mortality itself, and his relationship with Julia becomes a perverse reflection of Duane’s protective love. When Julia finally kills him, it is more than revenge—it is a symbolic act of reclaiming agency from an immortal predator who represents the endless cycle of abuse and consumption.

Varley’s death does not end evil but confirms that it can be confronted, even if only by those already marked by it.

Ray “Ray Ray” Sikes

Ray Ray Sikes exists mostly in flashback, yet his presence looms over the entire narrative as the origin of Julia’s trauma. A violent, drunken abuser, Ray Ray personifies the kind of mundane evil that breeds monsters like Varley by creating victims like Julia.

His death at the hands of Julia’s mother is both an act of liberation and the first moral rupture in Julia’s life—a killing justified yet scarring. Ray Ray’s cruelty and death become the template through which Julia understands violence: as both punishment and power, fear and survival.

Linda Shaw

Linda Shaw, Julia’s mother, is a tragic figure whose one act of violence—killing Ray Ray to save her children—costs her everything. Imprisoned and separated from Julia, she becomes a ghostly influence over her daughter’s conscience.

Through her, Rosson explores the moral ambiguity of survival: when protection becomes indistinguishable from destruction. Linda’s refusal to flee, her acceptance of punishment, and her final estrangement from Julia represent the novel’s ongoing meditation on guilt and consequence.

Julia’s eventual vow to “offer her mother a choice” at the end of the book signals not vengeance but forgiveness—a reconciliation of love and monstrosity.

Detective Scoggins

Detective Scoggins is the weary face of law and reason amid a world that defies both. Persistent, skeptical, and humane, he represents the limits of rationality in the face of supernatural horror.

His investigation into Varley’s crimes bridges the novel’s human and monstrous realms, grounding the chaos in procedural realism. Scoggins’s eventual enthrallment by Varley’s psychic manipulation and his brutal death illustrate how easily order collapses when confronted by ancient evil.

Yet his lingering moral clarity—his attempts to protect Julia and confront Duane—casts him as one of the story’s quiet heroes.

Bobby and Ian

Bobby, Duane’s volatile best friend, and his partner Ian serve as mirrors for Duane’s own contradictions. Bobby’s quick temper and loyalty embody the rough, masculine camaraderie of the bar world.

He is deeply flawed but fiercely loyal, providing Duane with the last tether to his human life. Ian, quieter and more observant, balances Bobby’s chaos.

Together, they highlight themes of male friendship, complicity, and moral compromise in an environment steeped in violence.

Adeline

Adeline is the mysterious figure who connects Julia to the supernatural underground. She represents knowledge, transformation, and the liminal space between death and rebirth.

As the keeper of the “Children’s Museum,” she becomes a dark mentor figure—offering Julia guidance and purpose within the shadow world she now inhabits. Adeline’s presence reframes the novel’s horror as a cycle of initiation and inheritance, suggesting that monstrosity can be both curse and calling.

Themes

Violence and Moral Corruption

Violence courses through Coffin Moon not as an external force alone but as a contagion that infects every life it touches. The novel begins with Duane’s struggle to contain his own anger—toward his rebellious niece Julia, toward the world that constantly seems to provoke him—and spirals outward into acts of brutality that echo across generations.

Keith Rosson constructs violence as both a learned behavior and a form of inheritance, passed down through families and communities like a cursed legacy. Julia’s childhood under the monstrous Ray Sikes introduces her to cruelty early, but her mother’s desperate act of shooting Ray in self-defense introduces a second, subtler corruption: the idea that violence can be justified, even redemptive.

Duane, a veteran haunted by past transgressions, carries his own moral wounds that blur the line between protector and destroyer. When the supernatural element enters through John Varley—a vampiric embodiment of endless violence—the theme takes on a mythic scale.

Varley represents the purest distillation of bloodlust, a being whose existence depends on consumption and destruction. Yet, even as Duane and Julia become literal monsters, the question Rosson raises is whether they were ever anything else.

Violence, once embraced as a solution, reshapes the human spirit until it becomes indistinguishable from the horror it sought to defeat. The novel’s conclusion, where Duane contemplates ending his undead life while rereading Heidi’s manuscript, shows the ultimate consequence: violence offers no catharsis, only cycles of guilt and survival that erode the self.

Family, Guilt, and Redemption

At its emotional core, Coffin Moon is about the yearning for family and the crushing guilt of failing it. Duane’s relationship with Heidi and Julia embodies a fragile hope—the belief that broken people can still build something resembling love.

But that hope constantly collides with the ghosts of their pasts. Julia’s trauma from Ray’s abuse, Duane’s buried sins from Vietnam and the bar incident, and Heidi’s quiet despair create a household held together by silence rather than healing.

When Heidi is murdered, Duane’s guilt consumes him, not only for failing to protect her but for the deeper suspicion that his own rage and interference invited Varley into their lives. His later devotion to Julia—protecting her even after she becomes a vampire—is a twisted form of penance, his attempt to salvage meaning from devastation.

Rosson portrays redemption not as absolution but as endurance: a willingness to shoulder the weight of one’s actions and still care for someone else. Julia’s affection for Duane, despite everything, redefines family beyond blood, suggesting that love persists even when humanity is gone.

By the end, when Duane reads Heidi’s manuscript and chooses, for one more night, to live, redemption becomes an act of persistence in the face of endless failure—a quiet refusal to surrender to despair.

Addiction and Self-Destruction

Addiction in Coffin Moon extends beyond substances; it is a compulsion toward escape, whether through alcohol, anger, or vengeance. Duane’s drinking is both symptom and symbol of his inability to confront pain directly.

His alcoholism mirrors his deeper dependence on violence as a coping mechanism—a way to assert control over a chaotic world. Julia, too, becomes addicted, not to liquor but to the idea of vengeance and later to blood itself.

Rosson treats these addictions with grim compassion, showing how they arise from trauma and loneliness rather than pure weakness. Joanne’s entanglement with the bikers, motivated by desperation to save her dying husband, reflects another variant of self-destruction: the rationalization of moral compromise for love.

The novel’s supernatural dimension amplifies this pattern—the vampiric thirst operates as a physical manifestation of addiction. Julia’s transformation literalizes what addiction does metaphorically: it remakes the body and soul, turns need into identity.

Yet amid the ruin, there are flickers of self-awareness. Duane’s repeated “three good memories” ritual is his attempt at sobriety of the spirit—a daily struggle to retain fragments of goodness.

Addiction here is not merely destructive; it becomes a mirror through which the characters see the cost of trying to numb grief and guilt, only to find themselves consumed by it.

The Supernatural and the Nature of Evil

The supernatural in Coffin Moon is not simply an element of horror but a moral and philosophical lens through which evil is examined. John Varley’s vampirism strips away the pretense of civility, exposing the predatory instincts embedded in human nature.

His inability to be photographed, his manipulation of others, and his centuries-long existence mark him as an embodiment of enduring malice—a figure who transcends mortal sin to reveal its timelessness. But Rosson blurs distinctions between human and inhuman evil.

The bikers who traffic heroin, the stepfather who abuses his family, the corrupt systems that enable cruelty—all these exist before any vampire appears. Varley is both a monster and a mirror, reflecting the potential for darkness already latent in Duane, Julia, and even Joanne.

As the novel progresses, the supernatural becomes inseparable from the psychological; vampirism functions as both curse and metaphor for moral infection. When Julia and Duane themselves become vampires, evil ceases to be externalized—it becomes a shared condition, something to resist rather than eradicate.

Rosson thus reframes horror from spectacle to introspection: the true terror lies not in monsters lurking in shadows, but in recognizing the same hunger, the same capacity for harm, within one’s own heart.

Survival and the Burden of Humanity

Throughout Coffin Moon, survival is depicted as both triumph and tragedy. For Duane and Julia, staying alive—first as humans and later as vampires—means constantly negotiating what must be sacrificed to keep going.

Each choice to live comes at the cost of something sacred: innocence, morality, or peace. Duane’s persistence after Heidi’s death initially seems heroic, but over time it becomes another form of torment, a refusal to let go that traps him in perpetual mourning.

Julia’s determination to avenge and later sustain herself transforms survival into a kind of moral exile. Yet Rosson refuses to romanticize martyrdom; he suggests that survival, however compromised, is still a defiance of annihilation.

The final image of Duane reading Heidi’s manuscript in the closed bar, surrounded by ghosts of memory, captures the dual weight of existence—how living on after tragedy means bearing both the curse and the privilege of remembering. Humanity, the novel implies, is not lost when one becomes a monster; it is lost only when one stops struggling to hold on to compassion.

Survival, then, becomes an act of faith: a belief that even amid decay, love and memory can still have meaning.