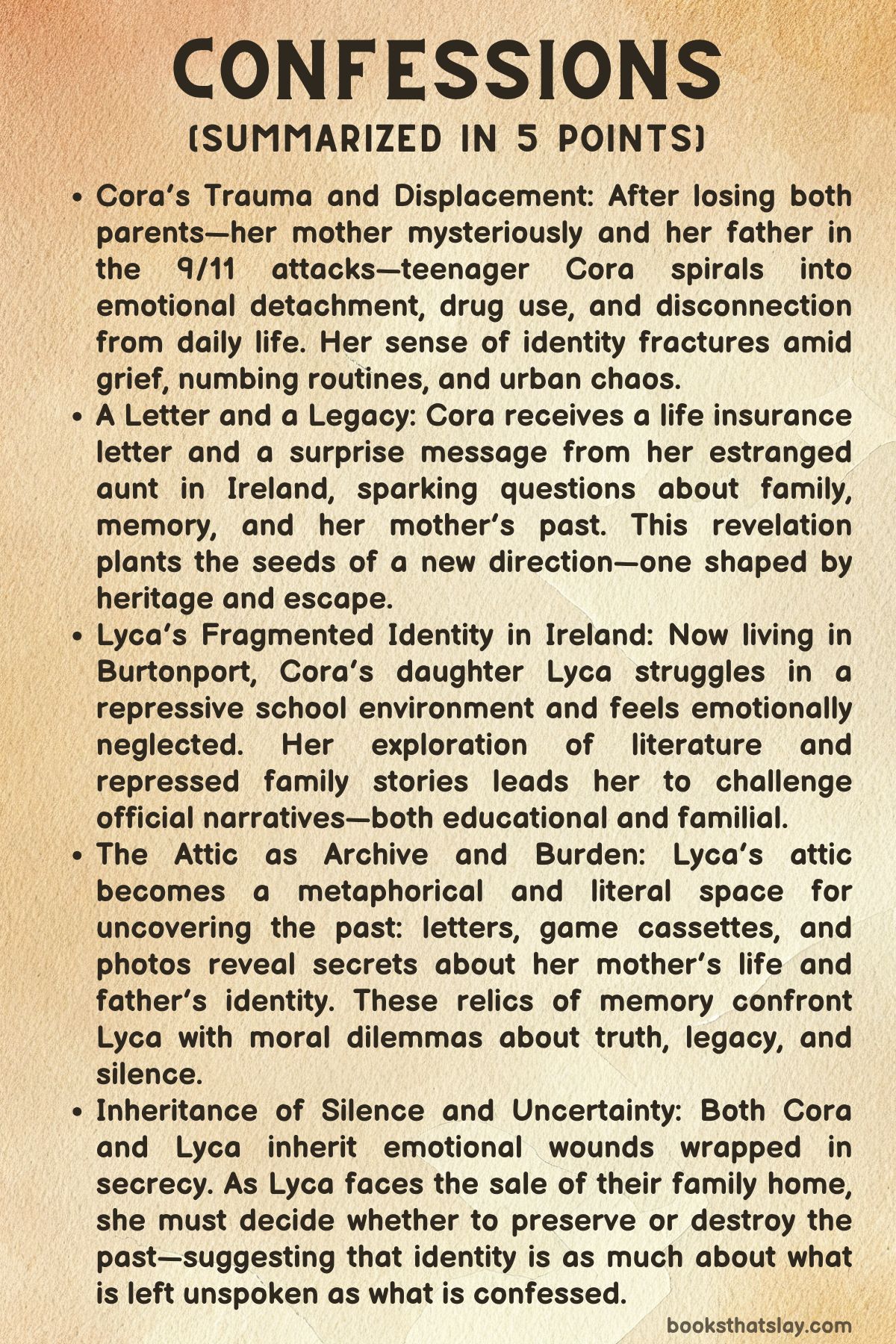

Confessions by Catherine Airey Summary, Characters and Themes

Confessions by Catherine Airey is a raw and intimate portrait of adolescent grief, identity, and survival.

Set in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, it follows sixteen-year-old Cora Brady as she copes with the presumed death of her father in the North Tower and the confirmed suicide of her mother. The novel presents an emotionally intricate look at how trauma disrupts time, memory, and self-understanding, filtered through the mind of a teenager on the brink. Through Cora’s dissociative wanderings, buried family secrets, and possible paths toward healing, Airey delivers a story about what remains when everything is gone—and how we begin again.

Summary

The story of Confessions opens with a searing image: Cora Brady’s mother is found dead, having taken her own life. Not long after, Cora’s father disappears during the attacks on the World Trade Center, most likely having jumped from the North Tower.

Though his death is not officially confirmed, Cora clings to the haunting image of the Falling Man, a photograph that both mesmerizes and torments her. She convinces herself it could be him, while simultaneously refusing to find out for certain.

This deliberate ambiguity becomes her way of preserving emotional survival, suspending herself between belief and denial.

On the morning of September 11, Cora is waiting for her boyfriend, Kyle, who ultimately fails to show. Their relationship is marked by a power imbalance—he manipulates her with drugs and empty promises, while she craves his approval.

In a state of emotional unrest and seeking escape, Cora takes acid. The hallucinations triggered by the drug blur the line between fantasy and reality just as the real-world terror unfolds.

Television broadcasts of the collapsing towers bleed into her trip, and the chaos outside merges with the internal chaos she’s already battling. Her father never calls.

In a haze of panic and despair, she overdoses on pills and disappears into unconsciousness, only to wake up to a permanently altered world.

Unable to process the magnitude of her losses, Cora turns to walking as a way to keep herself moving. It becomes her defense against inertia and emotional paralysis.

As she roams the streets of New York, she witnesses the collective mourning of a city—missing person flyers, makeshift shrines, donation drives—but she herself remains disconnected from it all. Instead of joining in rituals of grief, she seeks refuge in movie theaters, where scripted tragedy feels safer than real life.

This disassociation allows her to avoid confronting the weight of her emotions and the expectations placed on her as a survivor.

Time stretches and collapses in Cora’s recollections. Her routines lose coherence, and her sense of purpose frays.

Then, two letters arrive that shift her trajectory. One is from her father’s life insurance provider, confirming her new financial independence.

The other is from her aunt Róisín, her mother’s estranged sister living in Burtonport, Ireland. Suddenly, there’s a legal guardian in the picture, along with a tether to her mother’s past and a part of Cora’s heritage that she barely understands.

Róisín’s letter doesn’t pressure her; it simply extends a gentle invitation. The coincidence of the letter’s arrival and its origin feels uncanny.

Cora had once invented a game called Scream School as a child—a haunted boarding school supposedly set in Burtonport. That such a place might be real, and connected to her family, unsettles and intrigues her.

The memory of the game stirs fragments of her childhood, prompting Cora to think about what she inherited from her mother, not just genetically but emotionally and artistically.

Her mother had been an artist—quiet, erratic, and unrecognized. Her abstract pieces, long overlooked, take on new meaning as Cora links them to her own emotional experiences.

She begins to understand how grief, silence, and creativity are braided through their family’s story. Her mother’s mental illness becomes a crucial lens through which Cora reconsiders her own sense of detachment and the emotional gaps in her upbringing.

As she begins to absorb the implications of her aunt’s letter, Cora also starts to reengage with the world around her in small but concrete ways. She cleans her apartment, prepares oatmeal, reads the newspaper.

These acts, though simple, are profoundly significant. They symbolize the beginning of her reconnection with reality and a tentative desire to live with intention again.

The banality of these tasks provides stability—a contrast to the uncontrollable forces that have shaped her life.

The novel does not provide a clear resolution. Cora doesn’t decide whether or not she will go to Ireland.

But something has shifted. Where once she existed in a state of numbed detachment, she now holds a fragile curiosity about the future.

The letter from Róisín is the first expression of unconditional care she’s received in a long time. Its quietness, its lack of demand, gives Cora room to breathe and consider healing—not as a dramatic transformation, but as a gradual opening.

Throughout Confessions, Cora’s voice remains the central force. Her thoughts, scattered and searching, reflect the inner experience of trauma in a deeply authentic way.

She doesn’t process her grief through logic or narrative order; instead, her memories and observations come in fragments, loops, and sudden bursts. Her isolation is both a defense mechanism and a result of being failed by the adults around her.

The absence of guidance or stability after her parents’ disappearance makes her transformation all the more hard-won.

The novel is not about solving grief or overcoming tragedy in a clean arc. Instead, it’s about bearing the unbearable and learning how to live with ambiguity.

Cora is both frozen and moving, lost and seeking. Her walk through New York is less a journey toward a destination than a search for a reason to continue.

As her world cracks open—through memory, art, and the faint possibility of belonging somewhere else—she begins to glimpse life beyond survival. The story ends not with resolution, but with a shift in orientation: a readiness to consider hope.

Characters

Cora Brady

Cora Brady stands at the emotional epicenter of Confessions by Catherine Airey, a deeply wounded yet fiercely introspective sixteen-year-old navigating the aftermath of both personal and national trauma. Her psychological unraveling begins with the shocking death of her mother by suicide and is compounded by the presumed loss of her father in the 9/11 attacks.

The image of the Falling Man becomes a symbolic representation of her father and a psychological crutch, one she clings to as a means of maintaining denial and suspending grief. Cora’s character is shaped by this dual loss and the chaotic swirl of emotions that follows: guilt, abandonment, and a desperate search for identity and control.

Her coping mechanisms are erratic and self-destructive, including substance abuse and emotional withdrawal. Her toxic relationship with her boyfriend Kyle, marked by imbalance and drug use, underscores her vulnerability and yearning for intimacy, even when it is corrosive.

Cora’s decision to drop acid on the morning of the attacks illustrates a critical fracture between her internal world and external events—a hallucination so severe that reality becomes nearly unbearable. This collision of personal and national tragedy forces her into a state of dissociation, where walking the streets of New York becomes both a literal and metaphorical means of escape.

Despite her detachment from communal grief, Cora is hyper-aware of the rituals of mourning around her. She avoids participation, yet meticulously catalogs them.

This paradox suggests a deeper psychological need to witness grief without being swallowed by it. Her isolation is not born from apathy but from a fear of being consumed by feeling.

When she receives a letter from her aunt Róisín in Ireland, Cora confronts an opening—one that offers her a familial tether and a new sense of possibility. Her reaction to the letter, tinged with curiosity and fear, represents a subtle shift from nihilism toward healing.

Her cleaning, eating, and reading of the news by the end signal not resolution, but motion—a reclaiming of routine and identity.

Róisín Dooley

Róisín Dooley, Cora’s maternal aunt, emerges gradually throughout Confessions as a figure of resilience, suppressed longing, and eventually, creative self-actualization. Her introduction via a quiet, generous letter contrasts starkly with the emotional barrenness Cora has grown accustomed to.

Róisín represents a different path—one marked by survival through expression, creativity, and endurance. Yet her own life has been haunted by absence and loss, particularly the enigmatic disappearance of her sister Máire, Cora’s mother, and the emotional scars of growing up in a home gripped by grief and mental illness.

Róisín’s backstory unfolds across decades, from her youth in rural Ireland where she shared a complex and emotionally charged bond with her sister Máire, to her adulthood shaped by unrequited love, secrecy, and trauma. Her emotional vulnerability comes to the forefront during Georgina’s death and her entanglement with Michael, which is fueled by grief and the yearning for connection.

Her relationship with Michael is marked by emotional dependency, an unreciprocated desire, and the painful realization that she is a placeholder for someone else’s devotion.

Eventually, Róisín seeks empowerment through storytelling. The myths she weaves about the Screamers’ house and the stories she writes become metaphors for reclaiming agency and voice.

Her involvement with Scarlett Marten marks both an opportunity for reinvention and a dangerous flirtation with being consumed by someone else’s narrative once again. Scarlett’s vision for the house and Róisín’s pregnancy by Michael place her at a crossroads, torn between the stories written for her and the ones she might write for herself.

Her emotional arc is defined by the slow, painful process of recognizing her worth beyond abandonment and grief, and by choosing to forge her identity through creation rather than erasure.

Máire Dooley

Máire Dooley is one of the most elusive and enigmatic figures in Confessions, exerting tremendous influence on nearly every character despite her frequent physical absence. As Cora’s mother, Róisín’s sister, and Michael’s love interest, Máire serves as both muse and mystery.

Her childhood in Ireland was marked by brilliance and volatility, an intensity that captivated her father and later shaped her relationships. She communicated her emotional landscape through surreal architectural drawings, which became symbols of both her genius and repression.

The ghost game she invented with Róisín, rooted in village folklore, becomes a pivotal metaphor—one that mirrors the psychological tension between the sisters and prefigures the primal scream therapy house that catalyzes Máire’s transformation. Her intimate involvement with Michael adds layers of ambiguity and emotional pain, particularly for Róisín, who witnesses their connection and is left in the shadows.

The Screamers’ house offers Máire a brief but profound opportunity to reclaim agency. Her scream at the door is not one of terror, but of release, marking her attempt to define herself beyond familial expectation.

In New York, Máire’s transformation continues in isolation. At NYU, she attempts to rebuild her life, though she remains haunted by displacement and the unresolved traumas of her past.

Her artistic disillusionment and silence toward Róisín and Michael suggest a woman both forging a new self and suppressing an old one. Her emotional legacy—layered, contradictory, and unresolved—shapes the psychological terrain Cora must navigate decades later.

Michael

Michael, a mixed-race refugee boy from Northern Ireland, is both a connective tissue and emotional rupture point among the primary characters in Confessions. His presence in the Dooley family home in Ireland injects both warmth and disruption.

He is adopted emotionally by the family’s father, becomes romantically entangled with Máire, and later becomes the object of Róisín’s unrequited love. Michael’s character is defined by a yearning for belonging and identity—needs that remain largely unmet despite his relationships with the women around him.

Michael’s romantic idealism is directed toward Máire, but his actions toward Róisín reveal a painful ambivalence. His willingness to sleep with Róisín while emotionally fixated on Máire illustrates his inability to confront loss honestly or offer meaningful intimacy.

His later decision to join Máire in New York, rejecting Róisín’s emotional vulnerability, reveals a man caught in the pull of ghosts and dreams rather than the present.

His impact ripples forward into Cora’s life. While she initially believes Michael to be her father, the truth—his non-biological connection and role in her mother’s death—adds layers of betrayal and disillusionment.

Michael remains, throughout the narrative, a tragic figure—a man shaped by displacement, burdened by secrets, and incapable of giving the kind of love or stability others need from him.

Scarlett Marten

Scarlett Marten introduces a performative, almost theatrical flair to Confessions, embodying the tension between reinvention and appropriation. An Englishwoman who buys the Screamers’ house and turns it into a Victorian tea room, she presents herself as charming, whimsical, and ambitious.

Her fascination with Irish history, trauma, and femininity borders on fetishization, as she proposes to transform a site of psychic anguish into a nostalgic performance space.

Her relationship with Róisín is both romantic and manipulative. While she offers affection and attention, her motivations are deeply tangled with her own traumas—abandonment, adoption, and a complex relationship to her own Irish roots.

Scarlett’s suggestion of an abortion for Róisín is presented as a matter-of-fact offering of control, yet it underscores her tendency to script the lives of others. She doesn’t manipulate through overt cruelty, but through charismatic dominance, rewriting trauma as performance and intimacy as spectacle.

Scarlett’s final appearance, dressing Róisín in a corset that doesn’t fit, becomes a haunting metaphor: the costume of empowerment that, in truth, constrains. Her ambiguous blend of care and control, charm and coercion, renders her one of the novel’s most psychologically layered characters—one who represents both an opportunity for rebirth and a warning against losing oneself in someone else’s story.

Themes

Grief as a Fracturing and Reconstructive Force

Grief in Confessions is not simply emotional pain but a rupturing of time, memory, identity, and even reality. For Cora Brady, the death of her parents—her mother by suicide and her father presumably during the 9/11 attacks—destroys the continuity of her world.

This is not grief that yields catharsis; it is the kind that disorients and isolates, causing her to reject social rituals of mourning and instead retreat into a private limbo. Her grief manifests physically and psychologically: in her constant walking through New York, in her drug-induced haze, in her compulsive refusal to verify her father’s fate, and in her interactions with memory-laden objects like her mother’s artwork or her father’s insurance letter.

The image of the Falling Man haunts her not because of certainty, but precisely because it allows her to avoid finality. The ambiguity of her father’s end becomes a fragile psychological scaffold—one that allows her to simulate closure without actually confronting the raw truth.

The city’s collective mourning becomes background noise to her more chaotic interior mourning, a personal unraveling that mirrors the broader national trauma. Yet, within this chaos, grief also carries potential for reconstruction.

The appearance of her aunt’s letter becomes a pivot—not resolving the grief, but nudging it into motion. Cleaning, eating oatmeal, checking the mail—these mundane acts signal the slow emergence of a self no longer defined solely by loss.

The narrative suggests that grief doesn’t simply end; it morphs, becomes incorporated into the self, and eventually, paradoxically, enables a new form of continuity.

Silence and the Legacy of Unspoken Histories

Silence, both chosen and enforced, permeates every layer of Confessions, functioning as both a protective mechanism and a generational curse. Cora inherits silence—her mother’s withdrawn nature, her family’s fragmented backstory, and the cultural atmosphere of stoicism that surrounds both mental illness and national tragedies like 9/11.

Her response to trauma is to mirror that silence, avoiding conversations, evading public mourning, and refusing emotional vulnerability. This muteness extends beyond grief; it governs identity.

Cora knows little about her Irish heritage, her parents’ relationship, or the deeper contours of their emotional lives. The silence in her home is not just emotional—it’s historical.

Her mother’s art, abstract and overlooked, becomes a metaphor for this obscured lineage: visible but indecipherable, intimate but inaccessible. When she receives the letter from her aunt Róisín, the presence of familial memory takes the form of language—quiet, gentle, but substantial.

This invitation cracks the sealed vault of silence, offering Cora a narrative that predates her trauma and might shape a future beyond it. Even then, the silence doesn’t disappear; it is negotiated with, rather than resolved.

The story suggests that silence is not inherently damaging, but dangerous when it becomes the only language passed down. Cora’s tentative decision to not yet go to Ireland, but to consider it, marks the first time she actively engages with this inherited silence rather than being governed by it.

It’s a moment of transition—from the silence of erasure to the silence of contemplation.

Identity, Dislocation, and the Search for Origin

Cora’s crisis in Confessions is fundamentally one of dislocation—not just physical, but cultural, psychological, and spiritual. Her family is fractured not only by death, but by estrangement and immigration.

Her mother’s death and father’s disappearance leave her suspended between lives, caught in a liminal space where the past is mythologized and the future is deferred. Cora’s refusal to engage with the certainty of her father’s death or her own cultural roots is a refusal to be anchored, a protective vagueness that keeps her identity malleable.

Her sense of belonging is fragmented: she wanders through New York without home, without family, without context. Even her memories are unstable, especially the hallucinatory recollection of 9/11 which blends acid trips with real horror, revealing how blurred the boundaries of her reality have become.

The introduction of Burtonport—first through a childhood game, then through Róisín’s letter—reintroduces the concept of origin as something tangible. It’s not merely geographical; it’s ancestral, narrative, and psychic.

Burtonport is not just a place but a repository of memory and possibility, containing the roots that Cora didn’t know she lacked. Her contemplation of going there is not a geographical decision—it’s an existential one.

The identity she might find in Ireland is both inherited and self-invented, shaped as much by her imaginative memory of “Scream School” as by bloodline. The novel asserts that origin is not static but constructed, a convergence of memory, myth, and choice, and that healing might come not from returning but from finally choosing a direction.

The Intersection of Art and Memory

In Confessions, art operates as a vehicle for emotional residue, a medium where unspoken histories are preserved and interpreted. Cora’s mother’s art, described as abstract and neglected, becomes a posthumous archive of her internal world—a language of grief, illness, and disconnection that Cora only begins to understand after her death.

The textures, colors, and forms of this art linger in Cora’s memory, fusing with her own emotional landscape and complicating her understanding of her mother’s life. Art becomes a conduit for nonverbal expression—more durable than speech, more forgiving than language.

Cora’s engagement with memory is not intellectual but sensory. She doesn’t recall conversations as much as she recalls sights, sounds, and spaces—her father’s face through a TV screen, the sound of flyers rustling in the wind, the grainy texture of newspaper headlines.

These elements are not documented but embodied, and they mirror the way her mother painted—not literally, but impressionistically, with emphasis on emotional truth rather than factual fidelity. The imagined “Scream School” and its fictional geography reflect how art and memory can co-create reality, especially when facts are inaccessible or unbearable.

Her childhood imagination, once dismissed as play, re-emerges in adulthood as a symbolic map toward reconnection and selfhood. The act of remembering itself is artistic: selective, emotive, creative.

By integrating her parents’ legacy with her own acts of reflection and imagination, Cora doesn’t merely recall the past—she reshapes it. The story thus suggests that art is not a retreat from truth, but a necessary method for remembering, interpreting, and possibly surviving it.

Bodily Autonomy and Emotional Survival

Cora’s story is as much about the physical body as it is about the emotional psyche. In Confessions, her trauma is registered somatically—through her drug use, her physical deterioration, her incessant walking, and her numbing isolation.

Her body becomes a battleground, not only for grief but for control. The overdose she experiences following the 9/11 attacks is not just a cry for help but a rebellion against powerlessness.

Her drug use isn’t recreational—it’s a strategy for erasure, a way to obliterate sensation and thought, to reclaim agency in the only way she knows how. Her refusal to engage with food, her hiding in the apartment, her physical detachment from others—all reflect an attempt to take back control over a world that has repeatedly acted upon her without consent.

However, by the end of the novel, the small physical decisions she begins to make—cleaning, eating oatmeal, moving through the city with less urgency—mark the beginnings of bodily reclamation. These gestures are mundane but profound because they signify presence, intention, and care—elements absent for much of her life.

The theme of bodily autonomy is also echoed in the story’s quiet critique of how national tragedies often overshadow personal suffering. Cora’s individual body is in crisis while the public performs collective grief.

The dissonance between these levels of experience makes her feel alienated and unseen. Her gradual reinhabiting of her body, then, is not just survival—it’s resistance.

It is her way of asserting value in a world that allowed her to disappear without notice.