Cover Story by Mhairi McFarlane Summary, Characters and Themes

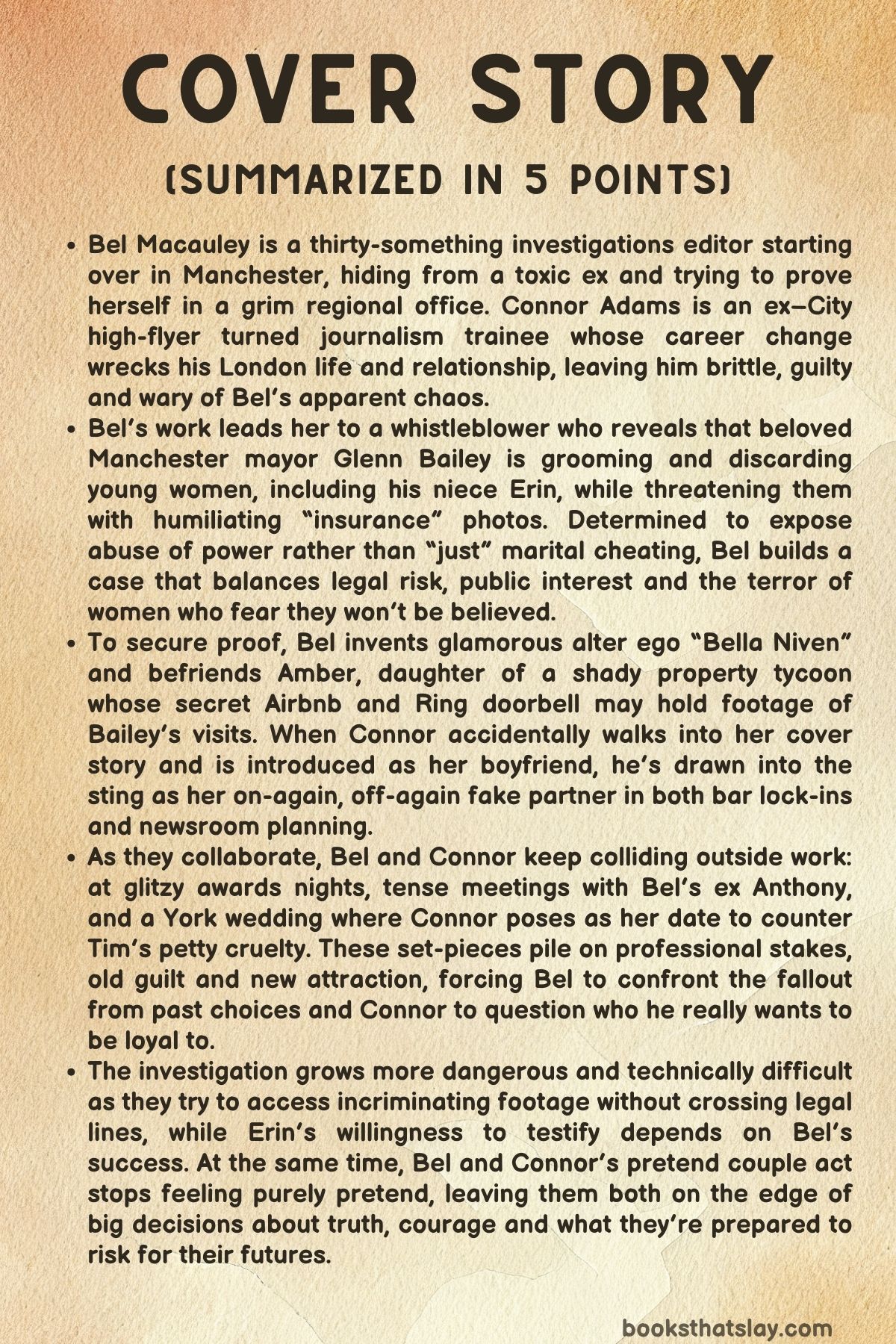

Cover Story by Mhairi McFarlane is a contemporary romantic comedy threaded through with office politics, investigative journalism and the messy business of starting over in your thirties. It follows Bel Macauley, an award-winning journalist fleeing a toxic affair, and Connor Adams, a burned-out City financier trying to rebuild his life as a trainee reporter.

Thrown together in a grim Manchester office, they clash professionally and personally while working on a high-stakes exposé of a beloved mayor. As Bel goes undercover and Connor confronts his past, their fake relationships, cover stories and real emotions start to collide in increasingly dangerous – and romantic – ways.

Summary

Bel Macauley, thirty-four and newly installed as investigations editor in Manchester, is determined to reinvent herself. She has a prestigious podcast under her belt, a stylish but overpriced flat in Ancoats, and a best friend, Shilpa, who alternates between chaos and fierce loyalty.

What Bel also has is a secret: she has moved cities and deleted half her life to escape Anthony Barr, a married ex-lover who will not stop sending obsessive emails. At work, she shares a shabby “nerve centre” with northern editor Aaron Parry, where their sarcastic friendship is disrupted by the arrival of a new trainee, Connor Adams.

Bel expects a clueless twenty-two-year-old and instead gets Connor, early thirties, immaculate suit, and clear disdain for her hungover fried-egg-roll entrance. From his side, Connor has walked away from a six-figure private equity job, is on a fraction of the salary, and is terrified his old depression is returning.

His girlfriend Jennifer resents the loss of their shiny London life, and Connor senses she cares more about their postcode than his wellbeing. First impressions between Bel and Connor are frosty: she thinks he is entitled and humourless; he thinks she is careless with people and overly pleased with herself.

In quieter moments, Bel and Aaron discuss her hit podcast episode, where she secretly tested a bar-safety “Ask for Amy” scheme to show how often staff failed to protect women. Connor challenges her methods, worrying about low-paid workers being dragged into public shame.

The clash exposes a difference in how they see power and responsibility. Soon after, Bel receives anonymous emails from “Grendel 505” offering a story about a powerful man and younger women.

She follows strict safety rules and meets the source, Ian, in Southern Cemetery. Ian reveals that his niece Erin was drawn into a secret sexual relationship with Glenn Bailey, Manchester’s hugely popular mayor, who now threatens to ruin her if she speaks out.

Bailey’s public image is saintly: teetotal, devoted family man, tireless civic leader. Erin’s experience is the opposite.

He seduced her after she left her internship, took her to a discreet Airbnb, then discarded her and hinted he had compromising images he could use against her. Erin is too frightened to go public, and Ian is racked with guilt but terrified of Bailey’s influence.

Bel can see the makings of a huge story but lacks evidence. She and Ian agree to continue talking via secure apps while she looks for other leads.

Bel’s personal life remains knotted. A night out with Aaron and Connor leads to cocktails with Shilpa, who is glamorous, blunt and instantly flirty with Connor.

In parallel, Shilpa gleefully shows Bel an Instagram picture of Bel’s ex-boyfriend Tim on a double date with his new partner, Rhiannon, a woman Bel actually likes. The news hits Bel harder than she admits.

Connor, drafted briefly into the conversation, suggests that when an ex clearly wants a reaction, the best move is not to give them one. Later, alone, he falls down an Instagram rabbit hole, piecing together Bel’s history with Tim and quietly revising his view of her.

The mayoral investigation deepens when Bel meets Ian again at a tiny café near Strangeways. Ian explains that Bailey used a Didsbury Airbnb owned by Gloria Kendrick, a property magnate with a murky past.

Bookings are handled by Gloria’s daughter Amber on a dedicated iPad, and the house has a Ring doorbell that stores months of footage. If Bel can prove Bailey visiting the property with Erin, Ian says, his niece will consider going on record.

Bel sees the risk but also the opportunity. She decides the only route is to get close to Amber herself.

Bel creates an alter ego, “Bella Niven”, a remote-working knitwear designer who is a glammed-up version of her real self. With blow-dries, rented accessories and a carefully crafted social media backstory, Bella becomes a regular at Amber’s bar, Ci Vediamo.

Bel studies Amber’s Instagram, mimics her social rhythms and stakes out a table where she can observe the bar and, hopefully, the hidden iPad. To accelerate their connection, she and Shilpa stage a dramatic fake FaceTime row about an extravagant hen trip.

Amber overhears, takes pity on Bella, and soon they are drinking together, bonding over weddings, money and difficult friends. Amber invites Bella to her thirty-fifth birthday lock-in and takes her number, exactly as Bel hoped.

The plan nearly collapses when Connor, scouting a hotel nearby, spots Bel in full Bella mode. With no time for explanations, she introduces him to Amber as her boyfriend.

After a startled pause, Connor throws himself into the story, supplying details of how they “met” at a Halloween party and performing the role of attentive partner. Once he leaves, Amber declares him gorgeous and is even more invested in her new friend.

In the taxi home, Bel realises that Connor, infuriatingly, has just become essential to her undercover work.

Their partnership tightens after a night when a neighbour’s pug sets off a false alarm and Bel, scared, clings to Connor. In the morning, Amber texts calling Connor a catch and swooning over how he looks at Bel.

Both are wrong-footed by this, noticing a shift they are not ready to discuss. At work, Bel quietly asks to keep Connor on the Glenn Bailey investigation and does not mention that his involvement started by accident.

When he discovers this, he realises she has risked her reputation to protect him and reconsiders his judgement of her.

Bel visits Ian’s house and meets Erin properly. In a slow, careful conversation, Erin explains that she never sent Bailey any nude photos.

Instead, he secretly took pictures of her while she slept and later used them as “insurance”, threatening to leak them if she complained. She is terrified of being dismissed as a silly fangirl and of seeing her career wrecked.

Erin agrees to go on the record only if Bel can first prove that Bailey uses the Airbnb. Bel promises to try, aware that the stakes have just risen.

Meanwhile, Connor’s family life arrives in the form of his charismatic brother Shaun, who visits Manchester for a weekend of toned-down fun. In a gold bathtub at Hotel Gotham, Connor confesses his breakup with Jennifer and his doubts about his old career.

Shaun, hearing about Bel and the Bailey sting, thinks she sounds formidable and that Connor might finally have met his match. At dinner with Shaun, Bel and Shilpa, Bel sees a more relaxed, funny version of Connor, while Shilpa later tells Bel that Connor is kinder and more principled than she allows herself to admit.

She hints that Bel is attracted to him; Bel furiously denies it, with little conviction.

Professionally, the barriers mount. On a stormy day at Bel’s flat, she and Connor pitch a detailed plan to their editor Toby and lawyer Albert: get Amber drunk at the lock-in, encourage her to bring the iPad out, observe the passcode and quietly swap it with a blank device while uploading the Ring footage elsewhere.

Toby and Albert shut the idea down as theft. Any copying must be done on-site; there will be no removing the iPad from the premises.

The scheme suddenly looks unworkable, yet Bel refuses to abandon the story and insists they still attend Amber’s birthday, hoping for an opportunity.

At the Northern Media Awards, Bel is acutely aware of both Glenn Bailey and the cameras; she even persuades the photographer not to capture unposed shots. Bailey approaches her to compliment her work, playing the charming fan, while she smiles and nods, knowing what he has done to Erin.

Later, Connor spots a goateed man watching Bel too intently and realises it is Anthony, the ex whose harassment drove her north. When Anthony confronts Bel outside, guilt-tripping her and using her full name in a proprietorial way, Connor intervenes.

He pretends someone important wants to see her inside, gently removes Anthony’s hand from her arm and guides Bel back up the steps. Only when they are safe does he admit he invented the interruption.

The gesture lodges deeply with Bel.

Soon Bel faces another emotional test: Tim’s sister Verity is getting married in York, and Bel is invited. Verity, influenced by Tim, tries to tuck Bel away at a back table and assumes she is coming alone.

Irritated at Tim’s pettiness, Bel lies that she is bringing a date. To make the lie real, she messages Connor and asks him to be her fake boyfriend for the weekend, warning there will be one bed.

After a moment of jokey resistance, he agrees and turns up with a suit and overnight bag.

At the hotel, Connor charms Bel’s family, who adore him on sight, and they are upgraded to an absurdly romantic suite. Before the wedding, Tim storms into the room to confront Bel.

He reveals he has pieced together Anthony’s obsession and concluded that Bel emotionally betrayed him before their breakup. He calls her a liar and a hypocrite.

She insists she did not sleep with Anthony while still with Tim, but she cannot completely untangle timelines to his satisfaction. At the height of the argument, Connor emerges from the bathroom, half-dressed, and calmly introduces himself.

He states there is a limit to how much of that he can hear someone say to “my girlfriend.” Tim, wrong-footed by the existence of a real boyfriend, retreats.

Bel breaks down once he has gone, calling herself a terrible person. Connor holds her and tells her she is not a monster, just human.

At the wedding, their “social North Pole” table of misfits turns out warm and fun, yet Bel still feels exposed under Tim’s glare. In the toilets, she overhears Verity and Rhiannon speculating that Connor is probably a gay colleague drafted in as a prop, and that Bel is trying to fix her self-esteem with an implausibly hot fake partner after cheating on Tim.

Humiliated, she tells Connor. He suggests that, if she wants the gossip to stop, they should kiss like a real couple somewhere they might be seen but not obviously performing.

On the edge of the dance floor, under cover of the music, Connor kisses Bel properly for the first time. The chemistry between them is undeniable, and Bel is shaken by how right it feels.

Back in their room, they climb into bed to watch a film, talking and cuddling until kissing starts again. Clothes are half off when Connor stops it.

He tells her he loved fake dating her but does not want to reduce their connection to a one-night stand they might both regret. Bel, full of old wounds, hears only rejection and assumes he does not desire her enough.

The rest of the night is stiff and overbright.

The next morning, Connor goes to breakfast alone and deepens his bond with Bel’s family, while she hides upstairs, determined to protect herself. On the drive back to Manchester, they talk lightly, skirting around the previous night.

Outside her flat, they thank each other for everything, promise vaguely to stay in touch, and say they will see each other at the office Christmas party. Bel privately decides she will not go; the farewell feels final.

Back in his near-empty Manchester flat, Connor goes for a run and realises that it is not the city he cannot bear to leave; it is Bel. What he feels is not a casual crush but love.

Sleeping with her once would not ease it; it would make walking away impossible. As he finishes packing, he opens a card his brother Shaun told him to save for departure day.

Inside, Shaun has written that Connor is in love with Bel and should do something about it. Laughing in disbelief, Connor tells his dad they need a quick detour to Ancoats.

Bel, alone in her flat, is certain she has ruined everything. Connor has gone, and she believes their friendship has been wrecked by her clumsy attempt to sleep with him.

When the doorbell rings, she braces herself for an unpleasant encounter with Anthony, but it is Connor, nervous and out of breath. She has clearly been crying.

Instead of blurting out a confession, she frames her feelings as a hypothetical story about “this guy at work” who she loathed at first, then grew to rely on, who saved her in difficult moments and became the person she trusted most. On their last night together she threw herself at him; he turned her down, and now he is leaving and she has realised she loves him.

Connor, heart racing, asks if the man is him. Bel admits that it is.

He shows her Shaun’s card and tells her Shaun is right: he loves her too. They talk honestly for the first time, admitting how fear made them cautious and sarcastic when they wanted the opposite.

He explains he stopped things at the wedding because he wanted something real, not because he lacked desire. She admits she was trying to play it cool rather than tell him he mattered.

At that moment, Connor’s dad appears at the door, desperate for the bathroom; Bel shows him in, then returns to Connor. With the pretence finally dropped, they kiss each other as themselves, and it is better than anything they imagined.

Connor and his dad drive south with Connor glowing, calling Bel “everything.” Bel phones Shilpa to tell her that she and Connor are together at last; Shilpa shrieks and reveals that Connor once said he could not imagine anyone loving Bel more than Tim had. After they hang up, Bel and Connor text back and forth, joking about how they could have slept together earlier if they had not been so cautious and how jealous they would have been of each other’s future partners.

They tease each other and flirt shamelessly, both dizzy with the relief of finally matching what they say to what they feel. With the Glenn Bailey investigation still hanging over them and a Manchester–London divide to navigate, they start a new chapter, this time with no cover stories between them.

Characters

Bel Macauley

Bel is the emotional and moral centre of Cover Story, a woman whose competence as an investigations editor contrasts sharply with the chaos of her inner life. At work she is sharp, witty and brave, the kind of journalist who will secretly test bar safety schemes and plan a complex undercover sting on a powerful mayor.

She has a strong sense of public interest and is prepared to put herself in uncomfortable situations to expose abuses of power, whether that is Glenn Bailey’s predatory behaviour or the failure of venues to protect women. Yet this same courage is complicated by a tendency to push herself to the brink, masking anxiety and exhaustion with junk food, self-deprecating humour and deliberately scruffy presentation.

Her personal history explains a lot of this contradiction. Bel is still shaped by two huge relational wounds: the obsessive, frightening affair with Anthony Barr, and the guilt over breaking Tim Hornby’s heart.

With Anthony she experienced coercion and harassment, to the point of uprooting her entire life, changing her number and leaving social media. With Tim she did the hurting: she ended a long relationship with a fundamentally decent man, while also having an emotionally blurred overlap with Anthony.

Bel internalises both experiences as proof that she is somehow dangerous and damaged, which feeds her self-loathing and her belief that she deserves to be punished by the Hornby family’s coldness. This makes her extremely self-aware and compassionate with other women who have been exploited, like Erin, but harsh and unforgiving with herself.

Bel’s relationship with deception is particularly interesting. Professionally, she believes in undercover work as a necessary tool against powerful liars.

She creates the persona of Bella Niven with almost frightening skill, adjusting her clothes, hair, voice and online presence to infiltrate Amber’s world. But as she grows to like Amber, she feels increasing guilt about how much she is using that friendship.

Similarly, she persuades Connor to participate in the undercover story and in the fake dating at Tim’s wedding, and then starts to blur the lines between performance and reality. The novel shows her learning that some forms of lying are costly even if the cause is just; the same armour she uses at work also prevents her from being emotionally honest.

Bel’s arc is one of learning to stop running and to accept that she can be flawed and still worthy of love. At the start she has fled York, fled Anthony, fled Tim’s disapproval and is hiding in Manchester as if geography can absolve her.

She projects negative traits onto Connor, insisting he is arrogant, shallow and unkind, partly because it is safer to assume the worst than to risk being wrong again about a man. Over time, as Connor repeatedly defends, supports and comforts her, she is forced to revise her assumptions.

By the end, when she confesses her feelings in the form of a “story about a guy at work,” she is finally willing to be vulnerable without a disguise. Her decision to stop defining herself by her worst mistake and to accept Connor’s love marks a move from self-punishment to self-acceptance.

Connor Adams

Connor starts Cover Story in free fall. He has walked away from a lucrative private equity career into a junior journalism role, effectively demoting himself in status, pay and certainty.

This decision looks irrational to people like Jennifer, but it comes from a deep unease with the life he has built. The City job has become his entire identity, trapping him in a high-earning but hollow role that exacerbates his depression.

There is a quiet desperation in his arrival in Manchester with his elderly father in the rain: Connor is trying to rebuild himself from the ground up, but he has no guarantee that this new path will work.

Character-wise, Connor is deeply conscientious and empathetic, but those qualities are initially hidden behind politeness and ironic detachment. He worries that Bel’s bar investigation might result in low-paid staff getting punished, which reveals a strong instinct to protect people who have little power.

He continues to visit the parents of a colleague who died by suicide, long after others have moved on. He remains connected to his own parents and brother, even when his life is in upheaval.

Yet in his romantic life he has been astonishingly passive: he lets his relationship with Jennifer wither rather than confronting its emptiness, and he postpones breaking up because he is conflict-averse and hopes circumstances will do the work for him.

Connor’s perception of Bel shifts gradually and is closely tied to his own emotional growth. At first he sees her as sloppy, unprofessional and smugly self-righteous, judging her hungover entrance and junk food habit.

As they work together, he notices her rigour, bravery and scrupulous thinking about the Glenn Bailey story. Bel’s decision not to drop him in it with Toby over the Didsbury incident quietly changes his view: he realises she has protected his reputation at cost to herself.

His feelings deepen during the undercover work and then at the York wedding, where he sees the full weight of guilt and judgement she lives under. His response in the hotel scene—physically comforting her while firmly refusing a one-night stand—shows his essential decency.

He wants something real, not a fleeting encounter that they will both regret.

A key part of Connor’s arc is moving from avoidance to active choice. He stops letting life happen to him and starts asserting what he wants, whether that is leaving finance, ending things with Jennifer, or finally rushing back to Bel’s flat instead of driving south.

Shaun’s card merely puts into words what Connor has already half accepted: he is in love with Bel, and he must act on it. His declaration at the end, and his willingness to risk rejection, signal his emergence from emotional paralysis.

Through Bel and the investigation he reconnects with his younger, idealistic self who wrote for the student paper, and he reconciles his need for meaningful work with his capacity for deep personal attachment.

Shilpa

Shilpa is Bel’s oldest friend and the human embodiment of “beautiful chaos.” She is messy, impulsive and occasionally selfish, living on Bel’s sofa, eating cereal and dropping drama like confetti. Yet beneath that unruly surface she is fiercely loyal and emotionally intelligent.

She is the person who knows both Bel’s worst mistakes and best qualities and stays firmly in her corner anyway. Her outrage about Anthony’s behaviour is protective rather than gossipy; she is the one who repeatedly raises the possibility of involving the police, recognising the danger Bel downplays.

Socially, Shilpa loves spectacle and performance. She stages the fake FaceTime fight about hen-do costs with relish, turning real frustrations about modern wedding culture into a weaponised scene to hook Amber’s sympathy.

She is also highly attuned to group dynamics, flirting with Connor and Aaron early on and instantly reading the chemistry between Bel and Connor that Bel is determined to ignore. Her casual remark that she cannot understand why Bel is so hard on Connor, followed by the dawning realisation that Bel is attracted to him, acts as a catalyst for Bel’s self-awareness.

Shilpa’s own romantic history, particularly with Rufus, mirrors some of the book’s themes around ego, social media and passive-aggressive performance. The double-date Instagram photo with Rufus and Tim’s new partners is a deliberate attempt to provoke, which Shilpa both indulges in and critiques.

She and Bel use humour and vengeance fantasies to manage their hurt, but Shilpa is also the one who appreciates Connor’s advice about not giving exes the reaction they crave. Ultimately she functions as Bel’s chosen family, grounding her in a sense that she is lovable, fun and worth fighting for, even when Bel herself doubts it.

Aaron Parry

Aaron is Bel’s office partner and comic foil, representing both the best and the worst of old-school regional journalism. On the surface he is sardonic, scruffy and perpetually unimpressed, mocking Bel’s attempts to brighten the grim Manchester office and teasing her about age, food choices and laziness.

Their banter establishes a sibling-like dynamic that initially excludes Connor and makes the newcomer feel like an intruder. Underneath the jokes, though, Aaron respects Bel’s skills and gradually acknowledges Connor’s work ethic, even if he communicates this in the vaguest possible way.

His background—being the third generation of a journalism “dynasty” via the Manchester Evening News—sets him up as a foil to both Bel and Connor. Where they had to hustle sideways into investigations and journalism from other paths, Aaron has inherited a defined route.

This makes him pragmatic and somewhat jaded; he is wary of risk and occasionally sceptical about big, ambitious projects. Yet he also provides continuity and local knowledge, knowing the cops, the pubs and the city’s rhythms.

His suspicion that there is “more going on” between Bel and Connor gives the reader an external confirmation of their chemistry, even as the two leads strive to act normal.

Tim Hornby

Tim is the ghost of Bel’s past and the embodiment of a “good man” who has been badly hurt. For much of Cover Story, we know him only through Bel’s memories of their shared childhood, their cousin-like closeness and their eventual romance that felt safe and inevitable.

Breaking up with him, especially with the emotional overlap of Anthony, has left Bel tormenting herself about having betrayed someone fundamentally kind. When Tim finally appears in person at Verity’s wedding, he is brittle, bitter and determined to rewrite the narrative in a way that restores his dignity.

His confrontation with Bel in the hotel suite is painful because both of them are partially right. Tim is justified in feeling that vital information was withheld and that there was an emotional betrayal, even if there was no physical affair before the breakup.

But he slips from hurt into cruelty, tallying Bel’s “lies,” calling her fake and hypocritical, and later briefing Rhiannon and Verity with a version of events designed to humiliate Bel. His comments about Connor probably being a gay colleague roped in as a prop reveal how much he needs to reassure himself that Bel’s new relationship can’t be real.

Tim becomes a cautionary figure: a decent person who, when wounded, chooses petty vengeance instead of healing.

At the same time, the novel does not demonise him completely. He is still the boy who once adored Bel, and his alarm at the idea of her losing self-respect hints that he knows she is more than her worst decisions.

His presence at the wedding, glaring from the speeches, embodies the way past choices can haunt a person socially. By forcing Bel to confront him head on rather than avoid the family forever, the book allows her to see that his judgement is not the final word on her character.

Anthony Barr

Anthony is the personal-scale predator whose shadow stretches over Bel’s present, a parallel to Glenn Bailey’s public-scale abuse of power. He is married, obsessive and entitled, framing himself as the wronged lover who is owed closure long after Bel has made it clear she wants no further contact.

His long, intense emails and refusal to accept the end of the affair push Bel into extreme avoidance: new city, new number, total social media wipe. When he appears at the Northern Media Awards, he deliberately uses her full name “Isabel” and references himself as “the one who came before you,” asserting ownership over her history in front of Connor.

Anthony’s behaviour illustrates how harassment can cloak itself in the language of romance and unfinished business. He is less obviously monstrous than Glenn, but his insistence on cornering Bel, his arm-grab outside the town hall and his refusal to respect her boundaries are chilling.

He represents the threat that can follow a woman long after an affair ends, and his presence explains why Bel is so skittish about being misjudged as the “bad guy” in her story with Tim. Connor’s decision to intervene with calm politeness, offering Bel an exit, doubles as a direct rebuke to Anthony’s coercive approach and symbolically rescues Bel from the pattern of being trapped in that dynamic.

Jennifer

Jennifer, Connor’s long-term girlfriend, is not portrayed as evil so much as ruthlessly pragmatic. She is invested in a particular version of adulthood: the expensive Stoke Newington flat, the path to a bigger property, the promise of children funded by a high income.

Connor’s decision to leave the City threatens that entire blueprint. Her drunken comment about him being a “trophy wife” exposes how she sees him: attractive, decorative and valuable mainly because of the lifestyle he can help maintain.

When he stops making big money, he becomes, in her eyes, a bad investment.

Her reaction to his discovery of her cheating is telling. Rather than grappling with what it says about their relationship, she wants to keep things going, as if the real loss would be status and stability rather than Connor himself.

Shaun’s assessment that she is acquisitive and hates losing a prize reinforces this reading. Jennifer thus functions as a mirror for Connor’s old life: glossy, outwardly successful, inwardly hollow.

His emotional numbness when he realises he no longer cares what she is doing online marks his quiet detachment from that world and from a version of himself who tolerated being valued for all the wrong reasons.

Glenn Bailey

Glenn Bailey is the charismatic, beloved Mayor of Manchester whose public image is the polar opposite of his private behaviour. In public he is a sober family man, civic hero and apparent supporter of women—he even flatters Bel’s podcast and claims to order his staff to listen to it.

In private he seduces much younger women like Erin, leverages his power and celebrity to ensure their secrecy and then discards them cruelly. His threat to frame Erin as a “slutty young girl” and his use of secretly taken nude photos as “insurance” show a calculated understanding of how misogyny and victim-blaming work in his favour.

Glenn represents a specific kind of modern villain: the socially liberal, media-savvy man who knows exactly what language of consent and empowerment to use in public while weaponising structural inequalities in private. His dealings with Gloria and the corrupt Ibiza property case also suggest a willingness to enter morally murky, possibly criminal territory whenever it suits him.

The Didsbury Airbnb functions as a physical symbol of his double life: an off-the-books pleasure palace that exists only because various people agree not to ask questions. Exposing Glenn is not just about one man’s sleaze; it becomes a test of whether institutions and the media will tolerate abuse when the abuser is popular and politically useful.

Erin

Erin, Ian’s niece, is the human face of Glenn’s predation. At twenty-four, she is young, ambitious and thrilled to be noticed by a celebrity mayor during her placement.

Glenn’s attention initially feels like mentorship and romance wrapped together, flattering her ego and offering the illusion of specialness. Once she leaves the office, their secrecy and the clandestine trips to the Airbnb intensify the power imbalance, isolating her from colleagues who might have offered reality checks.

The moment Erin reveals that the supposed “nudes” were actually non-consensual photos taken while she slept is crucial. It reclaims her from the stereotype of the foolish young woman sending reckless selfies and makes clear that Glenn’s behaviour is abuse.

Her terror about being cast as an embarrassing fangirl and her fear that speaking up will ruin her career reflect the real-world dynamics that keep women silent. Erin’s decision to cooperate only if Bel can first prove Glenn uses the Airbnb shows both caution and courage: she understands the stakes and demands that the story not rest solely on her word.

Her vulnerability deepens Bel’s determination and gives the investigation a personal urgency beyond professional ambition.

Ian

Ian is the reluctant whistleblower whose conscience finally outweighs his fear. As a communications worker for Glenn, he is close enough to see patterns that others can deny, but far enough down the hierarchy to be easily crushed if the Mayor turns on him.

His guilt is twofold: he helped Erin secure the placement that led to her exploitation, and he has continued working in an office he knows is saturated with hypocrisy. Reaching out to Bel under the pseudonym “Grendel 505” and arranging a meeting in a cemetery underscores his secrecy and dread.

Ian’s demeanour—nervous, hesitant but driven by concern for Erin—contrasts sharply with Glenn’s charm. He understands how much power the Mayor wields and how ruthless he can be, yet he is still willing to risk his career to give Bel a lead.

His practical suggestions about the Airbnb, the Ring doorbell and Amber’s iPad show that he has thought carefully about how to make the story provable, not just cathartic. Ian represents the difficult role of the insider who chooses integrity over self-preservation, and his involvement gives Bel’s investigation both legitimacy and emotional stakes.

Amber

Amber is one of the most morally ambiguous figures in Cover Story because she inhabits the grey space between complicity and ignorance. She runs Ci Vediamo and manages bookings for the Didsbury Airbnb, coming from a wealthy background that has insulated her from many consequences.

At first she is simply a target: the gatekeeper Bel needs to charm in order to access the Ring footage. The fake hen-do argument is designed to appeal to exactly the kind of woman Amber appears to be—someone immersed in wedding politics, costs and friendship drama.

Once Amber steps in with free champagne and genuine sympathy, she becomes harder to see as just an obstacle. She offers Bella kindness, solidarity and friendship, opening up about her life, inviting her to a birthday lock-in and even enthusing about Connor as a “gorgeous” boyfriend.

She is generous and gossipy rather than malicious, and there is no explicit evidence that she knows the full extent of Glenn’s behaviour. The tragedy of Amber’s role is that her warmth is being mined and exploited for a cause that is, objectively, in the public interest.

Bel’s growing guilt about deceiving her highlights the collateral damage of undercover journalism: sometimes, to expose a great wrong, you end up hurting people who never meant to do harm.

Gloria Kendrick

Gloria is a largely offstage presence whose history colours the entire Didsbury operation. A ruthless property magnate with a previous arrest in a major Ibiza fraud case, she is used to pushing the boundaries of legality and consequence.

The fact that Glenn chooses her property for his secret trysts signals that he is comfortable surrounding himself with morally dubious allies. Gloria’s reliance on a family-only booking system and a tightly controlled iPad suggests both a desire for discretion and an ingrained habit of doing business just out of sight of regulators.

Although we see Gloria primarily through Bel’s research and Ian’s account, she stands as a symbol of the kind of entrenched moneyed power that makes corruption resilient. Her suspended sentences in the Ibiza case reinforce the theme that wealthy people often skate by with minimal punishment, even when caught.

In that context, Bel’s argument to Toby and Albert—that Glenn’s association with Gloria is a corruption and blackmail risk—becomes even more pressing. Gloria embodies the kind of background rot that allows a politician like Glenn to act with impunity.

Toby

Toby, Bel’s editor, personifies the balancing act between journalistic ambition and institutional caution. He is impressed by Bel’s talent and trusts her judgement enough to hear out a risky undercover plan, but he is also acutely aware of complaints regulators, libel laws and the financial vulnerability of modern newspapers.

His first concern is whether the Glenn story is truly in the public interest, or just a sex scandal dressed up as something more. Bel’s insistence on the power imbalance and the corruption angle eventually convinces him, showing that he is persuadable when presented with a solid ethical framework.

Toby’s decision to bring the paper’s lawyer, Albert, into the conversation underscores his procedural mindset. He wants the story, but only if it is bulletproof.

His willingness to authorise up to six weeks of undercover work, within strict expense and oversight limits, signals both support and anxiety. Through him, the novel acknowledges that journalism is not just about individual bravery; it is also about institutions prepared to absorb legal risk.

Toby’s cautious yes allows Bel’s investigation to move from idea to reality.

Albert

Albert, the in-house lawyer, represents the legal conscience of the newsroom. Where Bel is driven by moral outrage, and Toby by a mix of ethics and commercial calculation, Albert is focused on what can be justified before regulators and in court.

His intervention around the iPad plan is crucial: he draws the line at theft and insists that any copying of the Ring footage must be done on-site. This constraint forces Bel and Connor to rethink their strategy, reminding them—and the reader—that even righteous causes have to operate within legal bounds.

Albert’s role is relatively small in terms of page time but significant thematically. He embodies the tension between what feels fair and what is lawful.

By siding with Bel on the overall public-interest value of the investigation but blocking her most intrusive tactic, he nudges the story toward a more complicated, less vigilante-style resolution. He also personifies the invisible safeguards that separate responsible journalism from outright vigilantism or hacking.

Shaun

Shaun, Connor’s exuberant brother in Washington, is both comic relief and emotional catalyst. He loves elaborate party weekends and teases Connor about his life choices, but he also sees his brother more clearly than Connor sees himself.

It is Shaun who recognises the pattern of Connor ending up in the wrong career and the wrong relationship, and it is Shaun who gently but firmly pushes him to admit that Bel is special. His story about the eulogy and Connor’s ongoing visits to the bereaved parents shows that he understands his brother’s depth of feeling and capacity for loyalty.

The card Shaun makes Connor promise not to open until departure day—bluntly stating “You’re in love with Bel. Do something about it.”—is a turning point.

It crystallises what has been obvious to everyone else, including the reader, and gives Connor the final nudge he needs to act. Shaun represents the affectionate, slightly chaotic sibling voice that refuses to let Connor hide behind politeness and inertia.

His presence reminds us that behind every major choice there are often family members cheering, teasing or cajoling in the background.

Rhiannon

Rhiannon, Tim’s long-time childhood friend and new partner, sits at an awkward intersection of loyalty and complicity. On one hand, she is someone Bel previously liked, which makes her presence at the wedding particularly painful.

On the other, she becomes the confidante to whom Tim vents his revised version of history, including the idea that Bel cheated and is now patching her self-esteem with an “implausibly hot” fake boyfriend who is probably gay. Rhiannon’s participation in bathroom gossip with Verity shows how easy it is to slide into reinforcing a narrative without ever hearing the other side.

Her discomfort at the wedding—caught between her loyalty to Tim and the residual warmth she may feel for Bel—adds another layer of social tension. Rhiannon’s role underlines one of the book’s quieter themes: stories about relationships are rarely told neutrally.

They are curated and passed along, shaped by hurt pride and the desire to feel righteous. In standing alongside Tim, she becomes part of the social machinery that judges Bel, but the novel leaves open the possibility that, in time, she might understand there was more complexity to the breakup than she was told.

Verity Hornby

Verity, Tim’s sister, uses wedding logistics as a subtle weapon. Her decision to place Bel at the “social North Pole” table at the back, then claim it was Bel’s own request, is an exercise in polite cruelty.

She frames herself as merely accommodating while actually enacting punishment on Tim’s behalf. Her call about the plus one, and her repetition of Tim’s assertion that Bel is “definitely single,” further expose how embedded family gossip is in her worldview.

The bathroom scene where Verity and Rhiannon dissect Bel’s supposed motives for bringing Connor shows her eagerness to interpret everything as a pathetic attempt at image repair. Verity embodies the collective judgement of the Hornby clan, unwilling to see Bel as a complex person who made a painful choice and instead casting her as the villain in a simple story.

Through Verity, the novel explores how families can become moral juries, handing down sentences that are hard to overturn.

Bel’s Family: Mum, Miles and Yasmin

Bel’s mother, brother Miles and his girlfriend Yasmin form a counterweight to the Hornbys’ coldness. Her mum is anxious about table plans but fundamentally wants everyone to get along.

She welcomes Connor with open arms, quickly deciding he is “wonderful” and even imagining how Bel’s late father would have adored him. This maternal endorsement hits Bel hard, both because it affirms her choice in partner and because it highlights how long she has felt unworthy of uncomplicated approval.

Miles and Yasmin are open, friendly and delighted by Connor, exchanging numbers with him and building an independent rapport. Their warmth demonstrates that not all of Bel’s past is hostile territory.

She has a family that loves her, even if they do not fully understand her guilt about Tim. The fact that Connor easily slots into this group, charming them without effort, reinforces the sense that he is a good match for her: he fits into her real life, not just the heightened world of investigations and undercover work.

Connor’s Dad

Connor’s father brings a quiet, older-generation presence to the story. He helps his son move to Manchester, worryingly watches his mood and ultimately drives him south again.

His concern about Connor’s depression is understated but constant; he recognises that this career change is not just a whim but a survival strategy. When Connor diverts to Bel’s flat on the way out of the city, his dad goes along with only gentle teasing, and his comically timed dash to the loo during the love confession scene adds a touch of farce to an intense moment.

After Connor and Bel finally get together, his dad’s observation that Connor looks truly happy carries weight because it comes from someone who has seen him at his worst. Calling Bel “everything” in front of his father signals how serious Connor is about her, and his dad’s acceptance rounds off the theme that love, to be sustaining, must integrate with family and everyday life, not exist only in secret, heightened moments.

Bryant, Cicely, Rufus and Other Minor Figures

Several minor characters in Cover Story serve as texture and thematic reinforcement. Bryant, the detective contact Aaron chats with at Schofield’s, signals Bel’s embeddedness in a network of sources and the porous boundary between journalism and policing.

Cicely, the nightmare former intern, appears mainly through jokes but frames the office’s initial dread about Connor and highlights the precariousness of trainee roles. Rufus, Shilpa’s ex-husband, co-stars in the performative double-date Instagram photo that catalyses some of Bel and Shilpa’s talk about vengeance and dignity, embodying the pettiness of social-media-era breakups.

Even small roles—like the woman who tells Bel she is “lucky” to have a boyfriend who looks like Aaron Taylor-Johnson, or the bar staff who fail the Ask for Amy test—contribute to the book’s exploration of perception versus reality. They remind us that strangers make quick, confident judgements about who is lucky, who is safe and who is powerful, while the truth beneath those snapshots is far more complicated.

Together, the ensemble of minor characters builds a world in which reputation, storytelling and power structures constantly interact, setting the stage for Bel and Connor’s intertwined professional and romantic journeys.

Themes

Journalism, Truth, and the Ethics of Undercover Work

In Cover Story, journalism is not a neutral profession but a constant negotiation between truth, harm, and personal cost. Bel’s work as an investigations editor shows how exposing powerful wrongdoing requires ingenuity, persistence and a willingness to push at ethical boundaries, yet the book never lets her forget that real people live inside her stories.

Her “Ask for Amy” podcast episode lays the groundwork: she secretly tests a safety scheme in bars, prioritising the protection of women over bar staff who might be disciplined for their failures. Connor’s cool question about whether workers were punished forces the reader to see that even righteous investigations can hurt the powerless as they challenge institutions.

That tension only heightens in the Glenn Bailey case. Bel’s plan with Amber’s bar and the Airbnb iPad requires a constructed persona, a network of lies, and deliberate emotional manipulation of someone who is not the main villain.

Lawyers and editors act as gatekeepers, insisting she cannot steal the iPad or put the paper at risk of regulatory punishment, but these limits also show how the system polices what counts as justified intrusion. The methods are discussed not as swashbuckling heroics but as painstaking logistics.

Connor’s move from private equity into journalism also frames investigative work as a moral reorientation. He gives up wealth to pursue something that feels socially meaningful, but the culture of journalism he finds is not simple idealism; it is office snark, resource constraints, regional politics and awards nights where the supposedly objective press mingles with politicians like Glenn.

The story keeps asking whether journalism genuinely serves the vulnerable, like Erin, or whether it sometimes uses their pain to create compelling narratives. Bel’s decision to involve Connor in the undercover operation, and her secrecy about how much she has protected him with Toby, underscores that investigations rely on trust and shared risk.

Journalism in the novel becomes a profession where methods, motives and consequences must be constantly reexamined, even while the public clamours for clear-cut heroes and villains.

Power, Coercion, and Sexual Exploitation

The Glenn Bailey storyline exposes how power can be abused in ways that leave almost no physical trace yet devastate the lives of those targeted. Glenn presents himself as a sober, family-oriented Mayor, a civic celebrity whose reputation is built on service and virtue.

Behind that spotless image is a pattern of grooming and discarding much younger women whose careers depend on his goodwill. Erin embodies this dynamic: a young intern seeking experience, flattered that such an important man notices her, swept into a relationship that she initially believes is mutual and special.

Glenn insists on secrecy, framing it as something romantic rather than isolating, and once he has got what he wants, he threatens to destroy her reputation if she speaks. The twist that she never actually sent nude photographs, and that he took images of her sleeping without consent, captures the horror of coercion that exploits both trust and unconscious vulnerability.

His threat of revenge porn weaponises the shame women are taught to feel about their bodies and sexuality, particularly in professional contexts. Ian’s guilt, as the uncle who helped Erin into the job, shows how power abuses ripple beyond victims into families and workplaces.

The Didsbury Airbnb itself operates like a hidden annex to Glenn’s office: off the official books, controlled by an elite property family, equipped with a Ring doorbell whose surveillance can be turned to his advantage. Bel’s own history with Anthony, the obsessive ex who stalks her across cities and platforms, runs parallel to Erin’s fear.

She has changed numbers, deleted social media, moved to Manchester, yet still cannot fully escape him. The novel shows that when powerful men and charismatic abusers act, the burden of self-protection falls almost entirely on women, who must uproot their lives while the men retain status and comfort.

Bel’s determination to bring Glenn down is driven not only by professional ambition but by recognition of this pattern; she understands that Erin’s story is not an isolated scandal but part of a larger culture where coercion is dressed up as romance and then rewritten as “slutty young girls using him” the moment a woman resists.

Identity, Reinvention, and Starting Over

Bel and Connor are both in the middle of re-making themselves, and Cover Story treats reinvention as both thrilling and painful. Bel has relocated to Manchester, taken a new job, and rented an expensive duplex that she can barely afford because it represents a break with the life Anthony tainted.

The flat, the new office, the reconfigured friendship with Shilpa as an almost permanent houseguest all express her desire to be someone who escaped and survived. Yet the past keeps intruding: Anthony’s emails, Tim’s presence at the wedding, the Hornby family’s quiet judgement.

Reinvention here is not a clean slate but a constant effort to manage how much of the old story still leaks into the new one. When Bel creates her undercover persona “Bella Niven,” that pressure intensifies.

Bella is an exaggerated version of who she might be in another life: more glamorous, girlish, glossy. She rents designer accessories, curates a whole social media tone in her head, adjusts her hair, nails and voice.

The seductive ease with which Amber accepts Bella suggests how readily the world responds to an edited self. At the same time, the deception gnaws at Bel; she likes Amber, knows she is exploiting that warmth, and wonders what parts of Bella are actually her own suppressed desires.

Connor’s arc mirrors this but from a different angle. He leaves behind a six-figure City identity that gave him status but also depression and a sense of hollowness.

His girlfriend Jennifer, who saw him as a “trophy wife,” anchors him to a life built on appearance and income; stepping into a trainee journalist role means accepting lower pay, a less glamorous postcode, and the feeling of being back at the bottom. Reinvention here is risky because it disrupts established relationships and forces him to confront how little of his previous life was built on genuine understanding.

As he settles into Manchester, the new version of himself emerges through small choices: reporting on strange local stories, being the diligent intern, allowing friendships with Bel and Aaron, opening up to Shaun and his father. Both protagonists are learning that reinventing yourself is less about one dramatic leap and more about daily acts of choosing different values, even while the old story keeps calling you back.

Money, Class, and the Cost of Security

Money shapes almost every relationship and decision in Cover Story, not as background detail but as a constant force that constrains choices and creates resentment. Connor’s career change is framed not only as idealistic but economically drastic.

He moves from private equity to a low-paid trainee role, immediately destabilising his London life. Jennifer’s fury about their Stoke Newington flat, the impossibility of ever getting somewhere larger, and the future children they might not afford highlights how class aspiration in modern cities is built on relentless income.

Her “trophy wife” comment slices to the heart of their dynamic: she values the lifestyle his salary provides more than his wellbeing. When he loses the salary, she treats him as aesthetically pleasing but practically useless.

For Connor, stepping down the income ladder means losing social capital among his old circle, but it also exposes which relationships depended on his earning power. Manchester offers something different: cheaper living, more modest social expectations, and a workplace where prestige is tied to bylines and contacts rather than bonuses.

Bel’s finances are also fraught. She rents a stylish duplex in gentrified Ancoats at a premium, in part to reassure herself that she has started afresh and belongs to a certain urban class.

Yet she eats junk food, nurses hangovers, and worries about expenses for the undercover work. The contrast between her shabby office and aspirational home underscores how class performance can be out of sync with underlying insecurity.

Around them, wealth often aligns with moral compromise. Glenn Bailey has political power and access; Gloria Kendrick is a property magnate whose Ibiza fraud scandal shows the ruthlessness behind glossy assets.

The Didsbury Airbnb is an expensive hideaway used to shield illicit sex from public scrutiny, while Amber herself “comes from money” and can own a stylish bar without the same financial anxiety that dogs Bel and Shilpa. Even social rituals like hen parties and weddings become economic battlegrounds: Shilpa’s staged Cancun hen argument taps into real grievances about the expectation that friends will spend thousands to celebrate other people’s milestones.

Verity’s wedding arrangements, hotel upgrades, designer outfits, and Instagram performances show how class and celebration are intertwined. The book suggests that security and respectability in contemporary Britain are often priced far beyond the reach of people trying to live ethically, and that this distortion pushes characters into careers, relationships and compromises they might otherwise refuse.

Friendship, Loyalty, and Chosen Family

Bel’s survival, both emotional and practical, rests on the web of friendships she maintains, and Cover Story presents these ties as a kind of alternative family that compensates for romantic and professional turbulence. Shilpa, chaotic and frequently irresponsible, is also her fiercest defender.

She eats cereal on Bel’s sofa, mocks her “open casket” hangover face, and yet is the first to worry that Anthony’s harassment might escalate to violence. She helps stage the fake hen-do row in Ci Vediamo, risking public humiliation to support Bel’s undercover work.

That mixture of exasperation and unwavering loyalty captures how long-term friends hold complicated truths about each other: Shilpa knows Bel’s flaws but never doubts her decency. Later, Shilpa is also the one who sees Bel’s attraction to Connor before Bel can admit it, pushing her to confront feelings she would rather bury.

At work, Aaron provides another form of friendship. His teasing, the shared jokes about greasy spoons and interns, and his grudging respect for both Bel and Connor create a sense of newsroom camaraderie that softens the grimness of their Deansgate office.

He plays the role of older brother, calling out nonsense, supplying gossip, and bridging tensions when he can. Connor’s family adds an intergenerational layer to this theme.

His seventy-six-year-old father drives him to Manchester, helps move him in, and later shares the car ride south when Connor finally admits his love for Bel. Shaun, larger-than-life in Washington, sends the card that bluntly states what Connor has been dodging: “You’re in love with Bel.

Do something about it.” That message cuts through his paralysis and becomes a catalyst for the climactic confession. On Bel’s side, her mother, brother Miles, and Miles’s girlfriend Yasmin create a warm, if occasionally meddling, family context.

They adore Connor almost instantly, providing the kind of welcoming chorus that suggests Bel deserves a partner who fits naturally into her life. Finally, the alliance between Bel, Ian, and Erin shows a different kind of loyalty: the solidarity of those trying to bring down a predator.

Ian’s torment over his role in Erin’s job, Erin’s tremulous courage, and Bel’s promise to do everything she can for them form a quiet bond rooted in shared purpose rather than blood or romance. The novel suggests that these networks of care – messy, overlapping, sometimes strained – are what allow people to withstand the harm done by lovers, bosses and abusers.

Love, Vulnerability, and Emotional Growth

The relationship between Bel and Connor charts a movement from guardedness to openness, showing love as something that requires both self-knowledge and risk. When they first meet, each misreads the other.

Bel sees Connor as vain, entitled, the sort of man who will “fail upward.” He looks at her as abrasive, unprofessional, eating fried-egg rolls in sunglasses and using him as a prop in an investigation. Their banter is sharp but defensive; neither wants to be the one who cares more.

Over time, shared experiences erode those misjudgements. Connor sees Bel’s commitment to exposing Glenn, her sensitivity with Erin, and the quiet ways she protects colleagues behind the scenes, like omitting his blundering entrance from her pitch to Toby.

Bel gradually recognises his conscientious approach, his visits to the bereaved parents of a colleague who died by suicide, and his discomfort with being treated as a decorative partner in Jennifer’s life. The fake relationship scenarios – first with Amber at Ci Vediamo, then the York wedding with Tim – act as laboratories where they test what intimacy with each other feels like.

Pretending to be a couple demands physical closeness, shared narratives, and a united front against external judgement. Their kiss at the wedding, designed to silence gossip about his sexuality and her supposed desperation, breaks the boundary between pretence and genuine desire.

Yet when they almost sleep together, Connor pulls back, terrified not of sex itself but of reducing something profound to a one-night episode that would implode once he leaves. Bel misinterprets this as rejection, reinforcing her fear that she is too flawed to be truly chosen.

It takes distance, a run through Manchester streets, Shaun’s card and Bel’s halting “story about a guy at work” to draw the truth into the open: they are both in love and both frightened. Their final conversation strips away coolness and performance, making space for awkward admissions, laughter, and the chaos of Connor’s dad interrupting.

Love here is not a lightning strike of certainty but the result of two people working through old guilt, class expectations, and professional crises until they can say what they actually want.

Public Image, Performance, and Social Media

From Glenn Bailey’s curated persona to Instagram revenge posts, Cover Story is preoccupied with how people stage their lives for an audience. Glenn’s entire political career depends on a constructed image of integrity and family devotion.

Media appearances, staff loyalty, and adoring public narratives shield him from scrutiny even as he exploits women in private. His threats to Erin rely on the power of that image: he is confident that if she speaks, the public will believe him, not her, because he has spent years training them to see him as a hero.

Social media operates at a more intimate level but with similar logic. Shilpa spotting her ex Rufus and Bel’s ex Tim on a double-date Instagram post reveals how platforms become arenas for subtle warfare.

The photo is carefully framed to be “accidentally” visible, a performance designed to inflict a particular emotion: jealousy, humiliation, the sense of being left behind. Bel’s reaction to seeing Tim with Rhiannon combines genuine hurt with awareness that she is meant to see this and feel exactly that way.

Anthony’s harassment also moves through digital space: long obsessive emails, relentless attempts to bypass her blocks. Bel deletes social media and changes numbers, but that act of self-erasure shows how the victim, not the aggressor, is often the one who must lose online presence to feel safe.

In her professional life, Bel understands performance at a granular level. She knows how to stage a podcast sting, how to set up a FaceTime row that will be overheard at Ci Vediamo, and how to whisper to the awards photographer to keep her out of candid shots that could blow her undercover work.

The “Bella Niven” persona is an extreme version of this: curated outfits, rented accessories, a backstory that fits Amber’s expectations of an Instagram-friendly friend. Connor, too, has managed public versions of himself: the sleek City worker in tailored suits, the dutiful boyfriend in a photogenic London life, the apparently unbothered trainee who jokes his way through awkward office dynamics.

As the story goes on, these images fray. The wedding exposes Tim’s private bitterness behind his self-presentation as the wronged good guy.

Connor’s removal of Jennifer’s photograph from his desk is a small but telling moment where display finally catches up with reality. The novel suggests that performance is unavoidable, but it challenges the idea that these curated selves are harmless.

Public images can be used to intimidate, humiliate, protect, seduce or deceive, and learning when to step out from behind them is part of the characters’ growth.

Guilt, Shame, and the Difficult Work of Self-Forgiveness

Many characters in Cover Story carry heavy guilt, and the book treats their attempts to live with or move beyond it as one of its most emotionally charged threads. Bel is haunted by multiple layers of remorse.

She ended a relationship with Tim, a man she still acknowledges as fundamentally good, in a way that left him shattered and his family estranged from her. The partial overlap with Anthony, even if it did not involve sleeping together, feeds her self-image as someone who lied and disappointed people who trusted her.

Tim’s later accusations at the hotel door, where he itemises her supposed dishonesty, strike her where she is already vulnerable; she collapses in tears, calling herself a terrible person. On top of this, she carries the ongoing fear and shame tied to Anthony’s obsessive pursuit, as if being harassed somehow reflects badly on her judgement.

Erin’s experience with Glenn is steeped in shame that does not belong to her. She worries that others will see her as an embarrassing fangirl who misread the situation, or as a promiscuous young woman who “knew what she was doing.” Glenn’s threat to use non-consensual nude photos ensures that any attempt to speak will feel like exposing herself to ridicule and moral condemnation.

Ian’s guilt is of a different flavour: he used his position to help Erin into the Mayor’s office, intending to do something kind, and instead feels he delivered her into harm. His desire to blow the whistle is driven not only by outrage but by the need to make amends.

Connor brings his own history of remorse over the colleague who died by suicide after a disastrous deal in his finance days. He continues to visit the man’s parents, an act of ongoing penance and care that marks him as someone unwilling to simply write off the past and move on.

Even his reluctance to sleep with Bel when emotions are high at the wedding is shaped by a fear of creating yet another situation he will regret. Across these stories, the novel suggests that guilt can be both corrosive and protective.

It can keep people trapped in self-loathing, like Bel insisting her worst mistake defines her, but it can also prompt acts of responsibility, like Connor’s visits or Ian’s whistleblowing. The path toward self-forgiveness is shown as slow and fragile: Bel begins to accept that she is “human, not a monster” when Connor says it with unshaken conviction, and when her family embraces Connor rather than punishing her for the past.

The ending, with Bel and Connor finally allowing themselves happiness, does not erase what they have done or suffered, but it hints that acknowledging imperfection openly can be the first step toward living with it rather than being ruled by it.