Culpability by Bruce Holsinger Summary, Characters and Themes

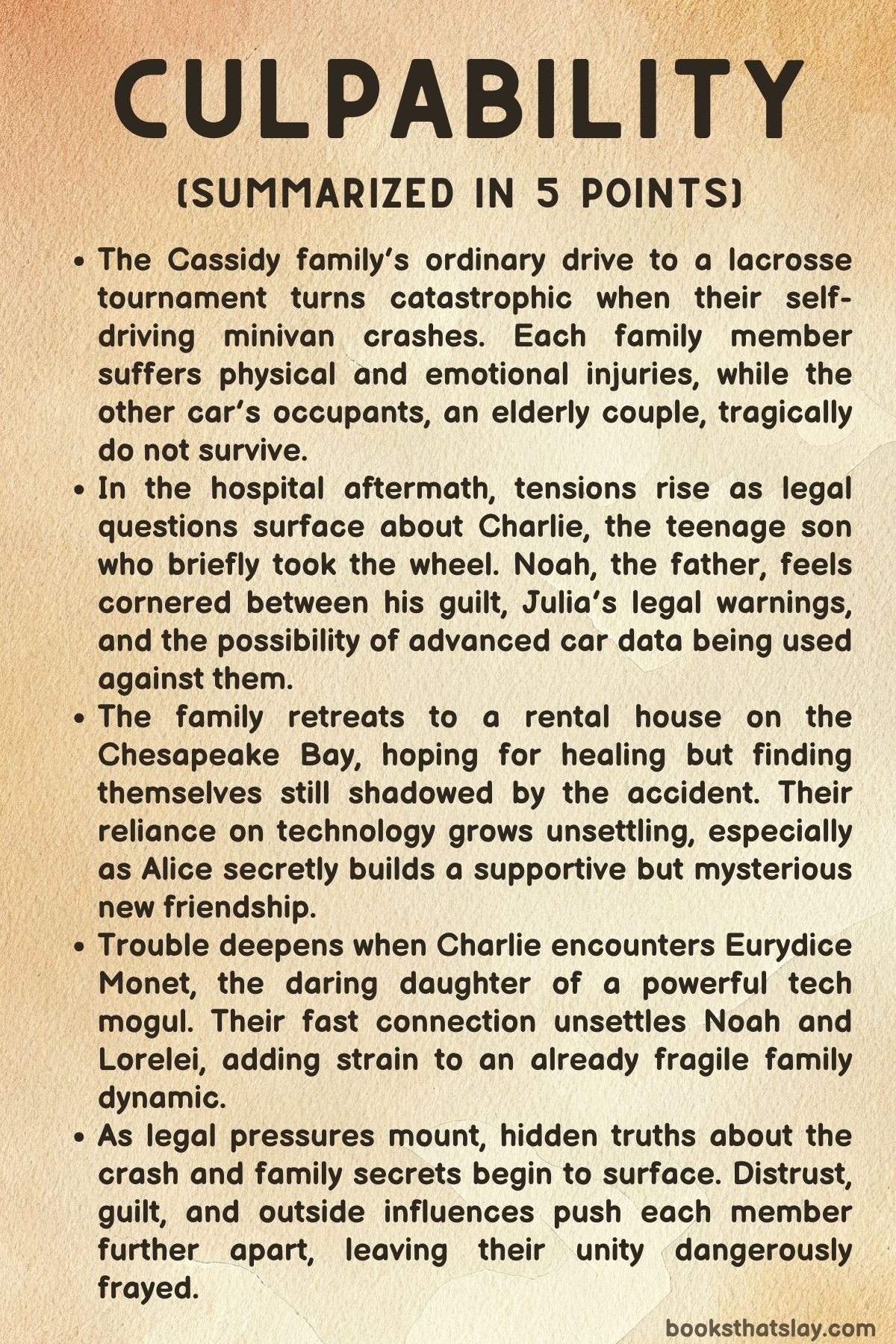

Culpability by Bruce Holsinger is a contemporary novel that explores the fragility of family, the consequences of technology, and the weight of guilt in the aftermath of tragedy. The story follows Noah Cassidy, a corporate lawyer, his wife Lorelei, and their three children after a horrific car accident caused while riding in their self-driving van.

Though the Cassidys survive, an elderly couple in the other car dies, and the family must navigate grief, blame, and the intrusion of artificial intelligence into their private lives. As secrets emerge and tensions mount, the Cassidys struggle to hold themselves together while unraveling under the scrutiny of law, technology, and their own hidden truths.

Summary

Noah Cassidy, a busy lawyer, travels with his wife Lorelei and their three children—Charlie, Alice, and Izzy—in their self-driving minivan en route to Charlie’s final youth lacrosse tournament. Tensions bubble in the car: Alice sulks, Lorelei is buried in work, Izzy plays cheerfully, while Charlie oversees the vehicle from the driver’s seat.

The family’s routine journey takes a sudden, devastating turn when Alice screams, a collision erupts, and the van flips violently. The aftermath is chaos—Lorelei’s neck injured, Alice bloodied and unconscious, Izzy’s leg trapped, and Charlie shaken but responsive.

Strangers help extract them as firefighters extinguish the other car, revealing the deaths of its elderly occupants, Phil and Judith Drummond.

At the hospital, Noah’s sister-in-law Julia and Lorelei’s brothers arrive, providing medical and legal support. The Cassidys are treated for injuries: Alice suffers a concussion, Izzy’s leg is fractured, Lorelei’s neck requires a brace, while Noah emerges unscathed.

Julia warns of legal fallout since Charlie, underage, was at the wheel moments before the crash, and Noah himself was distracted by work. Though the family is hailed in the press as the “Lucky Five,” the death of the Drummonds casts a heavy shadow.

Back home, healing proves harder than expected. Alice struggles with migraines, Izzy learns to move on crutches, Lorelei resents her brace, and Charlie grows distant, consumed by guilt.

Noah, physically fine, carries survivor’s guilt and feels inadequate as husband and father. Meanwhile, Alice begins texting a girl she met in the hospital, Emma, finding comfort in their growing friendship.

Detective Lacey Morrissey arrives to investigate, armed with data from SensTrek, the van’s artificial intelligence system, which logged every detail of the crash. Noah realizes the same technology designed to protect them could expose Charlie’s role.

Lorelei cooperates with Morrissey, leaving Noah uneasy. Seeking peace, the family rents a Chesapeake Bay house with an AI assistant named Calinda.

Despite attempts at normalcy—swimming, meals, games—their sense of safety remains fragile. Tensions flare when Charlie ventures onto the bay without a life vest, pushing Noah’s fears to the surface.

One day, Noah and Charlie paddle into a nearby cove marked with illegal “No Trespassing” signs. The place is artificial, with man-made beaches and security guards patrolling.

When Charlie slips into the water, armed guards intervene, and the two are photographed and threatened. They are startled when Daniel Monet, a powerful tech magnate, and his daughter Eurydice (nicknamed Dissee) arrive by helicopter.

Charlie catches Eurydice’s attention, sparking Noah’s unease about her influence.

Charlie soon becomes fascinated with Eurydice, researching her family online and later spending long hours with her. Their flirtation unsettles Alice, who resents her brother’s new obsession.

Lorelei meanwhile wrestles with her own inner turmoil. Once celebrated as a MacArthur “genius” grant recipient, she suffers from anxiety and guilt, heightened by the accident.

She obsesses over global tragedies and questions AI ethics, drawing parallels between their crash and reports of U. S. drones misidentifying targets in Yemen.

Eurydice boldly visits the Cassidys’ dock, deepening her bond with Charlie. He grows more carefree, while Noah grows more suspicious.

Lorelei’s anxieties sharpen, particularly as helicopters ferry guests to Monet’s lavish estate next door. When Charlie disappears with Eurydice for hours, Lorelei, panicked, confronts him and paddles to the Monet estate, forcing an uneasy introduction with Daniel Monet.

The family’s struggles worsen when Noah secretly connects Charlie with attorney Ramsay, creating tension with Lorelei, who believes legal defense will complicate matters. Charlie, angry and fearful about losing his scholarship or facing prison, lashes out at his father and withdraws.

Later, Noah discovers Daniel Monet secretly owns their rental house and arranged their air-conditioning repairs, revealing Lorelei has hidden her connections with him. This fuels Noah’s paranoia about possible secrets between his wife and Monet.

At Monet’s extravagant party, the Cassidys confront their fractured dynamics. Noah drinks heavily, suspecting Lorelei of deeper ties to Monet or even an affair.

Charlie and Eurydice’s romance unfolds publicly, while Lorelei’s disapproval of Monet’s AI projects becomes clear. As Noah’s suspicions fester, he stumbles upon Charlie and Eurydice together on the beach and, in a drunken outburst, blurts out that Alice revealed Charlie had been texting at the time of the crash.

Charlie feels betrayed, pointing out that Noah himself was distracted, making him equally culpable. Their father-son bond crumbles.

That night, Noah hallucinates a vision of Phil Drummond outside in a storm, shaken by guilt. The next morning, Detective Morrissey arrives with a search warrant for two phone numbers: Charlie’s and Izzy’s.

In a devastating turn, Izzy confesses she had been texting Charlie from the backseat moments before the crash, teasing him about Alice. Charlie’s distracted reply coincided with the collision.

Izzy sobs that she “killed those old people,” though Lorelei insists it wasn’t her fault. This revelation further fractures the family, as their fragile narrative of blame collapses.

Alice confides online to her friend Blair about Izzy’s confession, only to be taunted that she too bears blame. Meanwhile, Noah and Lorelei spiral further apart, arguing over secrets and loyalties, while Charlie withdraws completely.

When Noah goes to wake him for police questioning, Charlie is gone—vanished from the house.

By this point, every family member is caught in a spiral of guilt and mistrust: Noah consumed by paranoia, Lorelei weighed down by secrets and anxieties, Charlie fleeing into rebellion and romance, Alice brooding with bitterness, and Izzy crushed by her confession. With the investigation tightening and Charlie missing, the Cassidys are left fractured, their survival haunted not just by technology and tragedy, but by the unravelling bonds between them.

Characters

Noah

Noah, the father and central narrator in Culpability, is portrayed as a man caught between professional ambition, parental duty, and gnawing guilt. A successful corporate lawyer, he is initially consumed by work, drafting a memo during the family’s drive, and this distraction becomes a recurring symbol of his moral conflict.

After the accident, Noah emerges unscathed physically, but internally he spirals under the weight of survivor’s guilt and the suspicion that his negligence may have contributed to the crash. His strained relationship with Charlie deepens as both father and son confront each other’s culpability—Charlie for taking the wheel, and Noah for failing in his role as the supervising parent.

Throughout the novel, Noah’s paranoia about Lorelei’s ties to Daniel Monet reflects his insecurities, rooted in his more modest background and his fear of losing both control and trust within his family. He is at once protective and self-sabotaging, veering between desperate attempts to hold his family together and reckless decisions, such as drunken confrontations and exposing secrets.

Ultimately, Noah embodies the theme of flawed guardianship in a world where human frailty collides with technological oversight.

Lorelei

Lorelei is Noah’s wife and a figure of both brilliance and fragility. A MacArthur Fellowship recipient, she has long wrestled with anxiety and obsessive fears, which resurface with greater intensity after the accident.

Her injuries—both physical, with her neck brace, and psychological, in her obsessive fixation on culpability—mirror the family’s fractured state. Lorelei’s guilt is expansive: she feels responsible not only for the deaths of the Drummonds but also for broader tragedies involving AI warfare, such as drone strikes gone awry.

This obsession places her at odds with Noah, as she views the accident through a lens of systemic, technological failure rather than personal negligence. Her ambiguous connection to Daniel Monet, whether professional or more personal, underscores her complexity: she is simultaneously principled, skeptical of AI’s unchecked power, and yet entangled with its most prominent evangelist.

Lorelei’s contradictions—maternal love, intellectual rigor, fragility, and secrecy—make her a powerful yet unsettling presence in the family’s struggle to heal.

Charlie

Charlie, the eldest child, carries the heaviest burden of the accident. A star lacrosse player with a promising future at UNC, his identity as the family’s golden boy unravels after being implicated in the crash.

Initially, he withdraws into smoking, drinking, and guilt, showing the corrosive impact of both responsibility and adolescent fragility. His romance with Eurydice Monet, intoxicating and impulsive, serves as both escape and rebellion against his parents’ scrutiny.

Charlie’s confrontations with Noah highlight the generational rift—his resentment of parental authority, his desire for independence, and his sense that his father’s failures are as grave as his own. The revelation that Izzy’s texts triggered his distracted driving only complicates his guilt, showing how accidents emerge from webs of shared responsibility rather than single acts.

Charlie’s arc captures the volatility of youth under pressure, balancing his longing for freedom with the crushing fear of losing everything to one tragic mistake.

Alice

Alice, the middle child, emerges as one of the most psychologically complex figures in the novel. Injured in the crash and grappling with concussions and trauma, she responds with bitterness and cynicism, lashing out at her siblings and parents.

Her budding friendship—and possible deeper connection—with Emma, later replaced by her cryptic exchanges with Blair, demonstrates her search for solace beyond her fractured family. Yet Alice also becomes a catalyst for conflict, exposing Charlie’s texting during the accident and fueling Noah’s betrayal of his son.

Her bitterness stems not only from trauma but also from her sense of invisibility within the family, overshadowed by Charlie’s athletic success and Izzy’s childlike charm. Alice embodies both victimhood and agency: she is a wounded teenager, but also the sharp-eyed observer who punctures the family’s illusions, often with brutal honesty.

Izzy

Izzy, the youngest, represents innocence corrupted by guilt. Initially depicted as playful and carefree, she emerges as the unexpected source of the fateful texts that distracted Charlie.

Her confession to the family—tearfully insisting she “killed those old people”—is one of the most devastating moments in Culpability, highlighting how even the smallest acts of sibling teasing can ripple into tragedy. Despite her injuries and youth, Izzy carries an emotional burden disproportionate to her age, one that her parents struggle to soothe.

She becomes a symbol of the randomness and cruelty of fate, her childlike impulses colliding with catastrophic consequences. Yet, Izzy also embodies resilience, finding small joys in recovery and forcing her parents to confront the shared, distributed nature of responsibility.

Detective Lacey Morrissey

Detective Morrissey serves as both antagonist and truth-seeker. Persistent, professional, and unsettlingly precise, she embodies the intrusion of law and technology into the family’s private sphere.

Her reliance on the forensic data from SensTrek symbolizes the novel’s broader theme: the ways machines now record, judge, and expose human actions. For Noah, she is a threat, a figure who can unravel the fragile narrative they cling to.

Yet, Morrissey is not portrayed as malicious; rather, she represents impartial accountability in a world where guilt is never cleanly assigned. Her presence forces the Cassidys to reckon not only with legal consequences but also with the moral ambiguities of their choices.

Daniel Monet

Daniel Monet is the tech mogul whose presence looms over the second half of the narrative. Charismatic, powerful, and enigmatic, he embodies the seductive allure and danger of unchecked technological power.

His estate, with its artificial cove and surveillance-laden guards, symbolizes wealth’s ability to reshape both nature and law. Monet’s ambiguous connection to Lorelei raises questions of loyalty, secrecy, and influence, while his daughter Eurydice serves as both temptation and distraction for Charlie.

Monet represents the external force that destabilizes the family further, not by direct malice but by embodying the very system of AI, privilege, and control that has haunted them since the accident.

Eurydice (Dissee) Monet

Eurydice, or Dissee, is introduced as a vibrant, fearless teenager who disrupts Charlie’s brooding withdrawal. Her bold pursuit of him, her playful defiance of her father’s authority, and her magnetic charm make her both liberating and dangerous.

For Charlie, she represents a chance at joy and escape, yet her presence also widens the gulf between him and his family. Eurydice is not deeply developed in terms of backstory, but her symbolic role is powerful: she embodies the risks of temptation, the unpredictability of adolescence, and the intoxicating allure of rebellion in a world already destabilized by trauma.

Themes

Family, Guilt, and Responsibility

In Culpability, the family unit becomes both the site of trauma and the fragile framework for healing. Each member carries a distinct burden of guilt that fractures their ability to support one another.

Noah, as the father, is haunted by survivor’s guilt and by the knowledge that he was distracted by his laptop when he should have been the supervising adult. Lorelei’s guilt extends further than the accident, connecting to her own history of anxiety, professional pressures, and an acute sense of moral responsibility for both personal and global tragedies.

Charlie, at the center of the accident, becomes withdrawn and reckless, smoking and drinking to blunt the weight of knowing that his actions—or inattention—may have cost two lives. Izzy’s childish teasing, which triggered the texting that distracted Charlie, crushes her under a sense of undeserved blame, and Alice wrestles with bitterness and hidden resentments that manifest in silence or hostility.

The novel refuses to simplify this guilt into a single culprit, instead showing how shared responsibility and hidden secrets slowly unravel trust within a family. The accident functions as a magnifying glass: every flaw, every tension, every suppressed conflict rises to the surface, making the bonds that once held them together feel tenuous.

What the book captures most powerfully is how love and guilt often coexist, with each family member desperate to protect the others while simultaneously resenting the weight they impose. The Cassidys’ path to recovery is not about absolution but about negotiating the messy terrain of shared responsibility without destroying one another.

Technology and Its Threat to Human Agency

The self-driving minivan and its AI system become more than a plot device; they symbolize the paradox of technological advancement. Designed to protect, the SensTrek system records every movement, turning from guardian into silent accuser as forensic data threatens to incriminate Charlie.

Later, in the Chesapeake rental, the AI assistant Calinda echoes this theme, embedding itself into the family’s domestic space and reminding them that they are never fully free of surveillance or technological mediation. Technology here does not merely malfunction; it strips individuals of the ability to claim control over their own narratives.

Noah realizes that his word as a father carries less weight than the data harvested by the car. The family becomes trapped in a world where every choice—whether a text sent by Izzy, a distracted glance from Noah, or Charlie’s split-second instinct to take the wheel—can be dissected, recorded, and judged.

The novel extends this anxiety beyond the family’s tragedy, weaving in global examples of drone warfare and AI-driven military decisions that blur the line between efficiency and ethical disaster. Lorelei’s reflections on drone strikes underscore the terrifying consistency of this theme: whether in a war zone or on a suburban highway, technology assumes control, while humans are left to grapple with consequences they cannot fully comprehend or undo.

The book suggests that autonomy is increasingly an illusion, replaced by algorithmic judgment and opaque “black boxes” that dictate life, death, and culpability.

Power, Privilege, and Moral Corruption

The arrival of Daniel Monet and his daughter Eurydice adds a layer of social commentary, contrasting the Cassidys’ fractured family with the opulence and arrogance of unchecked privilege. Monet embodies the allure and menace of power built on technology, with his guarded estate, private helicopters, and cultlike following of admirers who view his AI innovations as salvation.

His world exists outside accountability, insulated from the consequences that haunt Noah and Lorelei. Where the Cassidys are consumed by guilt and fear of legal ruin, Monet thrives by bending systems to his will, even extending subtle control over the family by providing the rental home and orchestrating conveniences such as the AC repair.

Eurydice’s sudden intimacy with Charlie also illustrates how privilege seduces and destabilizes, offering him escape from trauma while simultaneously ensnaring him in a world governed by wealth and influence. The stark difference between the Cassidys’ fragile recovery and Monet’s unchecked dominance raises questions about who society allows to bear the weight of culpability.

Ordinary people are ensnared in legal, technological, and moral traps, while those with resources can manipulate systems to their advantage. This disparity becomes one of the novel’s most unsettling truths: guilt and responsibility are not distributed evenly, but often determined by power and status.

The Fragility of Safety and the Haunting of Trauma

Safety, in Culpability, is shown to be fragile and transient, constantly undermined by memory, chance, and fear. Even after surviving the crash, the Cassidys cannot reclaim a sense of security; every paddleboard ride, every car trip, every moment of separation threatens to collapse into another catastrophe.

Noah’s panic as Charlie drifts into rough waters, Lorelei’s fixation on tragedies beyond their immediate lives, and Alice’s bitter withdrawal all show how trauma lingers long after the physical wounds heal. The family is nicknamed the “Lucky Five,” yet the novel underlines how deceptive that label is, for luck does not erase the constant presence of danger.

Ghosts of the accident resurface in Noah’s hallucinations, in Izzy’s confessions of blame, and in the silence that hangs between family members during even mundane activities. Trauma reshapes their interactions, dictating how they speak, what they hide, and how they attempt to move forward.

The juxtaposition of ordinary pleasures—pizza, swimming, games—with looming dread underscores how survival does not equate to peace. What makes the novel resonate is its refusal to present recovery as linear or complete.

Instead, it portrays survival as living in the shadow of catastrophe, where safety can never again be assumed but must always be questioned, guarded, and negotiated.