Cultish by Amanda Montell Summary and Analysis

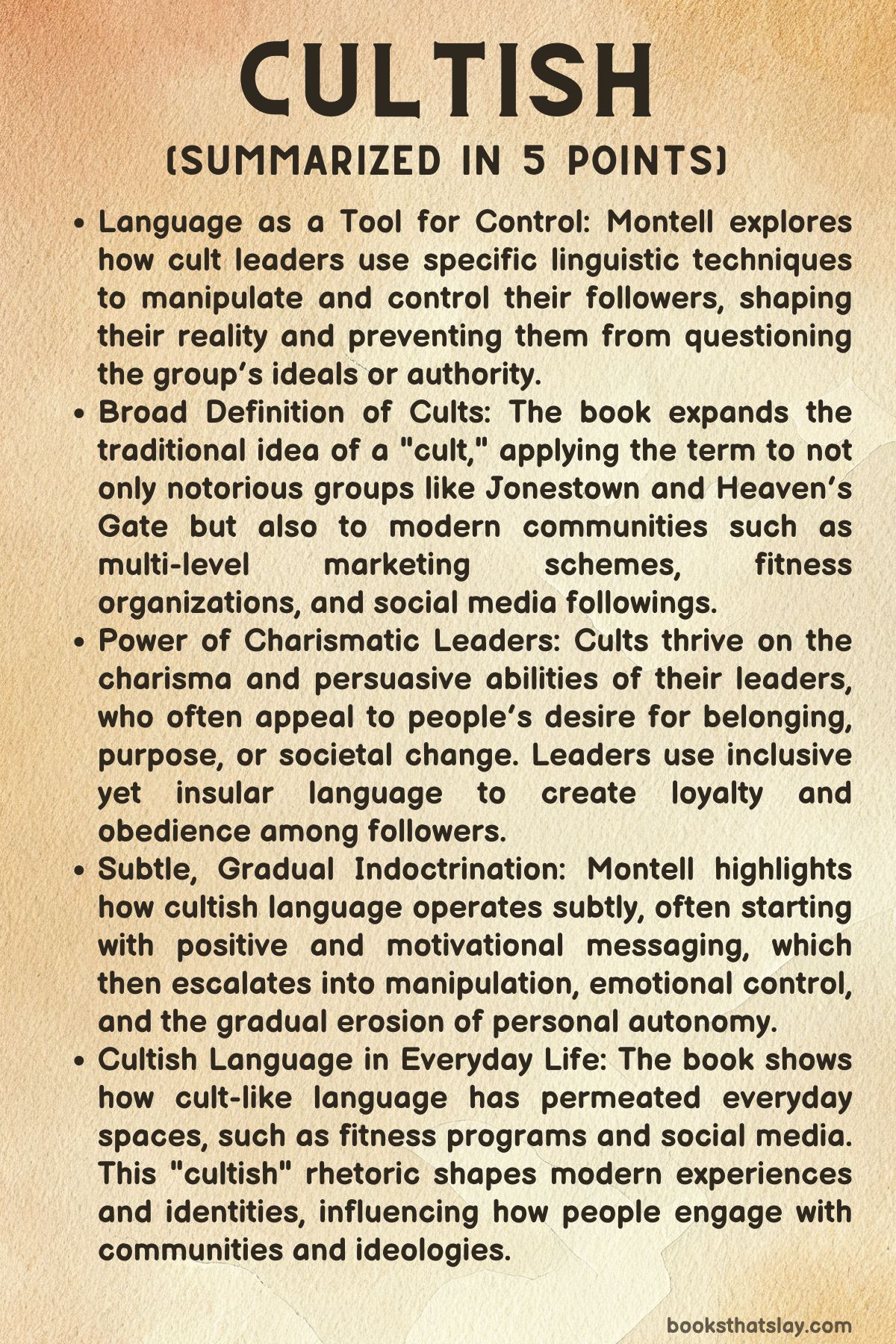

Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism by Amanda Montell delves into the fascinating world of cults, exploring how language is the central tool cult leaders use to influence and control their followers. Montell reveals how specific linguistic strategies can manipulate perception, creating a reality where members believe in the cause or community with unwavering devotion.

By examining notorious cults and other modern groups—like multi-level marketing schemes, fitness communities, and social media influencers—Montell shows how “cultish” language extends far beyond the groups we typically label as cults, shaping various aspects of modern life and human behavior.

Summary

Amanda Montell’s Cultish explores the profound influence of language in cults, uncovering how carefully crafted words and phrases can manipulate people into adopting extreme beliefs or behaviors.

Montell begins by dissecting the meaning of “cult” and how its perception has evolved over time. She dispels the myth that people in cults are simply brainwashed, pointing to deeper, more complex social and psychological forces at play.

Through personal anecdotes, Montell introduces her father’s experience in a cult called Synanon, revealing how this early exposure to cult dynamics sparked her interest in the subject.

She notes that many people are intrigued by cults because they want to understand what drives others to follow leaders with seemingly dangerous or irrational ideals.

Montell then dives into some of the most infamous cults in history, such as Jonestown and Heaven’s Gate, both of which ended in mass suicides.

These groups, led by charismatic figures like Jim Jones and Marshall Applewhite, offered their followers utopian promises at times when people were feeling particularly disillusioned with society and the government.

Jones, for instance, used his socialist ideals and powerful rhetoric to draw in followers who believed in racial equality and social justice, only for them to find themselves trapped in a deadly situation in the jungles of Guyana.

Similarly, Heaven’s Gate followers were led to believe that their deaths would take them to a higher plane of existence.

Montell highlights how language helped create an insular world where questioning the leader’s vision became nearly impossible for members.

The book also examines more contemporary and controversial religious groups, including Scientology and the Children of God.

These groups use language in ways that seem harmless or even empowering at first, but gradually strip away individuals’ autonomy. Montell herself experienced Scientology firsthand, uncovering how language is used to coax people deeper into the organization without realizing how much control they are surrendering.

These groups often rely on love-bombing, emotional manipulation, and carefully timed revelations to condition followers into blind devotion.

Expanding her scope beyond traditional cults, Montell turns her attention to multi-level marketing (MLM) companies.

She explores how MLMs adopt cult-like language to create an environment where success seems achievable for anyone willing to invest enough time and effort. Using grandiose promises of financial freedom and personal empowerment, these companies often ensnare people in a cycle of recruiting and selling.

Montell shines a spotlight on the way language plays a role in keeping participants motivated, even as the vast majority fail to reach the promised success.

The world of fitness also reflects cultish tendencies. Montell examines how fitness programs like CrossFit and SoulCycle use empowering mantras and community-building language to inspire intense loyalty among their participants.

While some groups foster a healthy sense of motivation, others blur the lines, encouraging extreme behaviors that can lead to physical harm or emotional exploitation.

Montell calls attention to how fitness groups sometimes manipulate members into pushing beyond their limits or confessing personal traumas.

Finally, Montell delves into the role of social media and its influencers, which she argues have become a new breed of cultish community.

The language of influencers, designed to engage followers and build personal brands, manipulates how people see themselves and interact with the world. In this digital age, Montell suggests, cult-like behavior has become an integral, unavoidable part of the online experience.

Character Analysis

In Cultish, Amanda Montell’s focus is primarily on groups and systems rather than individual characters, as the book is an analysis of linguistic patterns and group psychology. However, certain historical and societal figures play key roles in understanding the dynamics of cults, their leaders, and their followers.

Rather than using a traditional fictional character-driven narrative, Montell treats real-life individuals and groups as the “characters” that she investigates. These include cult leaders, followers, and entities like corporations or fitness communities that adopt cult-like strategies.

Amanda Montell (as Narrator and Author)

Amanda Montell herself is the most significant “character” in the book. She serves not only as the author but also as a guiding voice throughout the text.

Her personal connection to cults, particularly through her father’s experiences with the Synanon cult, frames her approach and gives the book a personal, investigative tone. Her father’s history influences her skepticism of cultish rhetoric and provides an emotional thread that ties the research to her own life.

Montell positions herself as both a detached observer and an insider with a familial stake, adding depth to her role as the narrator. Her awareness of the persuasive power of language emerges from this personal history, making her analysis both academic and reflective.

Jim Jones

Jim Jones, the infamous leader of the People’s Temple and the orchestrator of the Jonestown massacre, is one of the most analyzed figures in the book. Montell delves into Jones’s background, emphasizing his intelligence, charisma, and manipulation skills, which enabled him to attract a large following.

His public persona as a progressive integrationist who supported racial equality helped mask his more sinister motivations. Montell portrays Jones as a master of language, someone who used rhetoric to tap into the ideals and anxieties of his followers, ultimately convincing them to commit mass suicide.

His character becomes emblematic of the dangers of language used for coercion and manipulation.

Heaven’s Gate Leaders: Marshall Applewhite and Bonnie Nettles

Montell also analyzes Marshall Applewhite and Bonnie Nettles, the leaders of Heaven’s Gate, another notorious cult that ended in mass suicide. Applewhite, in particular, is presented as a tragic figure—an enigmatic leader who exploited people’s disillusionment with society and their desire for salvation in an extraterrestrial paradise.

He used a mixture of sci-fi spiritualism and religious language to build an insulated community of followers. Applewhite’s ability to convince his followers to participate in their own deaths illustrates the profound impact of linguistic manipulation on vulnerable individuals.

Like Jim Jones, Applewhite’s persuasive power and his followers’ ultimate sacrifice make him a key figure in Montell’s exploration of how cultish language creates an alternate reality.

MLM Leaders and Corporate Figures

In her examination of multi-level marketing companies (MLMs), Montell does not focus on specific individuals as much as on corporate figures who employ cult-like tactics to keep participants engaged. She portrays the leaders of MLMs like Amway, LuLaRoe, and Optavia as faceless figures who capitalize on positive rhetoric, false promises, and the allure of entrepreneurial freedom to manipulate participants.

These companies adopt a communal language of empowerment, framing their participants as “boss babes” or independent business owners while, in reality, exploiting them financially. Though the actual leaders of these MLMs are not personalized in the same way as figures like Jim Jones, Montell illustrates how their collective use of language creates a culture of manipulation similar to that found in traditional cults.

CrossFit and SoulCycle Leaders

In the fitness section, Montell analyzes the dynamics between fitness instructors and their followers, especially in programs like CrossFit and SoulCycle. Here, the “characters” are fitness leaders who use cultish tactics to create devoted followings.

CrossFit, for instance, is portrayed as a community that celebrates physical hardship, injury, and extreme loyalty. The leaders of these groups are not always identified by name, but Montell examines their methods—pushing participants to extremes, fostering a sense of exclusivity, and using language that encourages dependence on the group.

SoulCycle, on the other hand, highlights individual instructors who command a near-worshipful following from participants, blending motivational language with personal empowerment. Montell paints a picture of these leaders as charismatic, sometimes problematic figures who wield power over their clients by controlling the emotional and physical environments.

Social Media Influencers and Gurus

The final set of characters analyzed by Montell are the modern social media influencers and online “gurus” who shape the language and behavior of their followers. Unlike traditional cult leaders, these influencers operate on a global scale, using platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube to build micro-cults around their personalities or brands.

Montell discusses how these influencers, through carefully curated content, create parasocial relationships with their followers, who in turn develop fanatical loyalty. The influencers’ ability to manipulate identity, belief systems, and self-perception through language and imagery echoes the tactics of more traditional cults.

Montell’s exploration of these figures underscores the pervasive influence of cultish language in everyday life, even beyond the boundaries of what one might traditionally consider a cult.

Analysis and Themes

The Power of Language as a Tool for Manipulation and Identity Formation

Amanda Montell’s Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism delves into the way language functions as an insidious tool in shaping and controlling individual identities within cults, whether traditional or modern. The book explores how the manipulation of language creates a sense of belonging, a unified identity, and often, a detachment from reality.

In discussing notorious cults like Jonestown and Heaven’s Gate, Montell reveals how linguistic techniques such as repetition, specialized vocabulary, and slogans serve as mechanisms for isolating members from society, instilling fear of outsiders, and compelling loyalty to a charismatic leader. Through rituals, chants, or peculiar jargon, language becomes a means of reprogramming individuals’ perceptions, distancing them from former identities, and convincing them to redefine their existence according to the cult’s ideology.

The resonance of this linguistic manipulation is not limited to radical religious groups but extends into the world of fitness regimes, MLMs, and social media. By carefully designing language, leaders can maintain control over followers while simultaneously making them feel autonomous.

Emotional Vulnerability, Ritualistic Conditioning, and the Cultic Pattern of Coercion

Montell’s analysis uncovers the deep psychological framework behind cult indoctrination, where language is a bridge between the mind and emotional vulnerability. Cults exploit this emotional vulnerability through a series of rituals and practices that condition individuals to rely on the group for validation, safety, and purpose.

Montell points out that such conditioning often begins with love-bombing—a process where new recruits are overwhelmed with affection and attention, fostering a strong sense of belonging. This pattern then shifts into coercion through various linguistic tactics like guilt-tripping, emotional manipulation, and gaslighting, causing members to question their personal beliefs and even their own perception of reality.

The success of these rituals lies in their incremental nature—people are slowly guided into deeper involvement, often without realizing they are being manipulated. The use of praise and mantras in fitness cults like SoulCycle, or MLMs like Amway, may seem harmless at first, but Montell illustrates how such groups leverage the same mechanisms as destructive cults, subtly transitioning from positive reinforcement to coercive loyalty.

Ideological Subversion through Charismatic Leadership and Social Identity Fragmentation

Montell’s investigation into the role of charismatic leaders, particularly figures like Jim Jones or leaders within MLMs, highlights the dangerous intersection of ideology and identity fragmentation. Cults, as Montell describes, often prey on individuals who are searching for purpose, justice, or community, particularly during times of social unrest or personal turmoil.

The charismatic leader becomes a symbol of hope, an embodiment of a utopian vision, but also the nucleus around which the group’s identity revolves. Through speeches, sermons, and communications, these leaders skillfully craft ideological frameworks that are difficult to refute because they promise salvation, enlightenment, or material success.

Montell argues that what distinguishes these leaders is their ability to fragment the follower’s social identity, making the cult the primary source of meaning while diminishing external affiliations like family, career, or social connections. This fragmentation is sustained through the ongoing use of cultish language, which redefines the follower’s world into a binary “us vs. them” dichotomy, pushing them to disconnect from mainstream society.

Cultural Shifts, Crisis of Institutions, and the Rise of Secular and Micro-Cults

One of the more nuanced themes in Cultish is how Montell situates modern cult-like behavior within the broader cultural and institutional crises of our time. The distrust in government, corporations, and established religions—particularly in Western societies—has left a vacuum, which is increasingly being filled by secular groups that share cultish traits.

These groups—fitness organizations, MLMs, and even social-media followings—reflect the shifting social landscape where the line between community and cult becomes blurred. Montell suggests that the rise of micro-cults, where intense loyalty is directed towards individual leaders within broader organizations, reflects our fragmented, digital age where the search for personalized meaning and identity is at its peak.

Fitness instructors, for example, can build cult-like followings distinct from the brand they work for, engaging members in ways that echo traditional cult tactics like rituals, mantras, and emotional disclosures during moments of physical weakness. Montell’s discussion of how these fitness cults push followers towards injury, while simultaneously blaming them for any harm incurred, demonstrates how the cultural obsession with self-optimization can parallel the self-sacrificing devotion found in more radical cults.

The Language of Digital Fandoms and the Transformation of Cultish Behavior through Algorithmic Influence

In her concluding analysis, Montell broadens her scope to examine how cultish language has been weaponized in the age of social media. Algorithms curate content that reinforces echo chambers, and influencers often exploit cult-like tactics to create deeply loyal followings.

These digital spaces have transformed traditional cultish behaviors into new forms of digital fanaticism, where social media gurus and influencers manipulate language to foster dependency and tribalism among their followers. Through practices like building in-group jargon, monetizing parasocial relationships, and fostering a sense of exclusivity, these modern figures of authority establish hierarchies and dynamics that mimic traditional cult structures.

Montell argues that while these digital cults might not lead to mass suicides or dramatic acts of violence, they nonetheless demonstrate the same psychological mechanisms at play. In particular, they use language to obscure critical thinking, heighten emotional dependency, and push followers towards a singular vision of success or belonging.

This theme raises critical questions about free will in the digital age, particularly in an environment where influence is mediated through curated content and algorithmic engagement. By connecting traditional cults with modern cultural phenomena, Montell’s work challenges readers to reconsider the scope and definition of fanaticism in the 21st century.

She reveals that cultish dynamics are not relegated to fringe religious groups, but are pervasive in everyday social structures, making the power of language all the more relevant in contemporary discussions about autonomy, identity, and control.