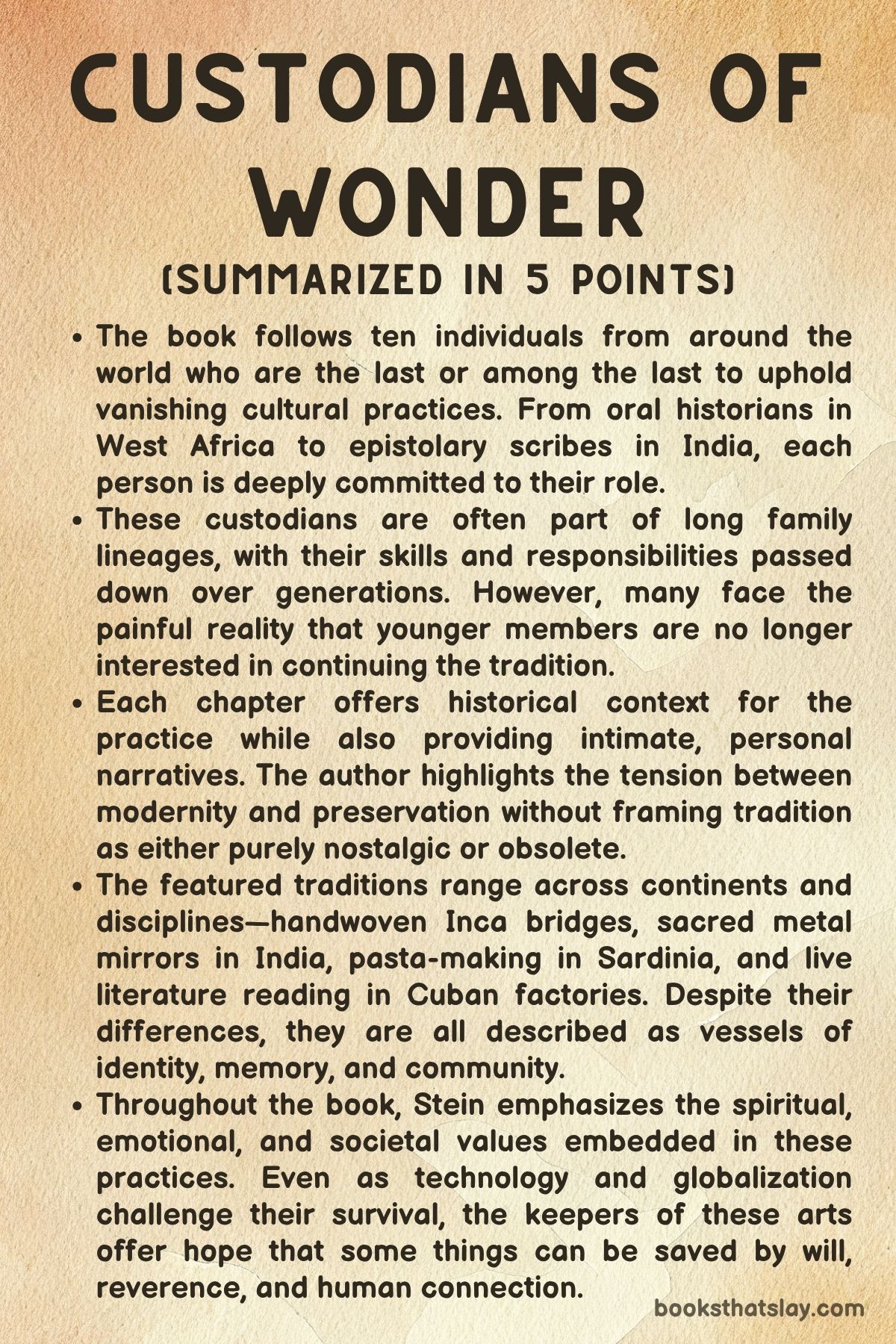

Custodians of Wonder by Eliot Stein Summary and Analysis

Custodians of Wonder by Eliot Stein is a nonfiction exploration of disappearing traditions and the extraordinary people keeping them alive in the modern world. With global breadth and emotional intimacy, Stein chronicles the lives of those who serve as living vessels of cultural memory—from griots in West Africa to soy sauce brewers in Japan and night watchmen in Sweden.

The book showcases how ritual, heritage, and identity can be passed on not through documents or technology, but through voice, rhythm, and practice. At once personal and historical, it illuminates the quiet resilience of those who refuse to let ancient knowledge vanish in silence.

Summary

Custodians of Wonder opens in West Africa with the story of Balla Kouyaté, a modern-day griot descended from the first djeli appointed by Sundiata Keita, founder of the Mali Empire. The griots, or djelis, have long served as oral historians and cultural stewards, using memory and music to sustain their civilization’s stories.

Balla, raised in Bamako, Mali, grew up steeped in this tradition while coping with a physical disability that left him unable to walk until he was seven. Guided by his father, the official keeper of the Sosso-Bala—a sacred 800-year-old balafon—Balla became a master of this ancient instrument, which is tied to both his lineage and the spiritual history of the Mandinka people.

His journey took a transformative turn when he moved to the United States in 2000 with his sister, chasing dreams of musical opportunity. Reality struck hard, as he lived undocumented and worked menial jobs while practicing his music in secrecy.

Despite these hardships, Balla’s dedication led to recognition. Collaborations with major artists and academic roles allowed him to share the balafon with a wider audience.

Eventually, he was honored as a National Heritage Fellow in 2019. The death of his wife marked a profound personal loss, yet it also led him to create a family album that helped him reconnect his American experience with his Mandinka heritage.

In returning to Mali and Guinea with his children, Balla honored a lineage of oral tradition that, even amid diaspora, continued through him.

The next story moves to Ystad, Sweden, where the fading profession of the night watchman is embodied in the quiet determination of Roland Borg. In a town that retains its medieval feel, Roland performs a role inherited from his father and grandfather, blowing his horn every fifteen minutes from the watchtower each night.

His dedication has remained firm even after suffering a stroke, revealing the depth of his bond to the town and its people. Though modern security measures now exist, Roland’s nightly presence provides a spiritual and emotional anchor for the townspeople.

His calls are more than ritual; they are a continuity with the past, comforting and human. During a dangerous episode involving a serial arsonist in southern Sweden, it was Roland who first noticed and alerted authorities, reaffirming his role not just as a symbol but as a vigilant protector.

However, the tradition faces an uncertain future. Roland’s son has chosen a more modern security job, and no official succession plan exists.

Deputies may fill in occasionally, but none carry the same familial or emotional legacy. As Roland continues his watch, the tradition hangs in the balance, its preservation reliant not on necessity but on will, memory, and emotional investment.

The book then shifts to Japan, where Yasuo Yamamoto, a fifth-generation soy sauce brewer on the island of Shōdoshima, works to rescue an endangered culinary tradition. In his warehouse, 87 towering cedar barrels—kioke—house microbial life critical to the fermentation of authentic soy sauce.

Once standard across Japan, this method now accounts for less than 1% of national production. Modern soy sauce is made quickly in steel tanks, sacrificing the complexity and richness of traditionally brewed shoyu.

Yamamoto’s awakening came after an early career in supermarkets, where he saw firsthand how mass production stripped food of meaning. Returning to his family’s Yamaroku Brewery, he recommitted to the slow, ancient methods of his forebears.

Recognizing the scarcity of kioke, he learned barrel-making himself and began holding workshops to pass on the craft. His reverence for the bacteria inside his barn—speaking of them as having personalities and sensitivities—demonstrates the intimacy of his relationship with nature.

He sees fermentation as a form of collaboration between human and microbe, a philosophy central to washoku, the traditional Japanese cuisine protected by UNESCO for its emphasis on seasonality, harmony, and spiritual gratitude.

Despite declining interest in rural traditions and an aging population, Yamamoto has built dozens of new barrels and hopes to raise international demand for traditionally brewed shoyu. His mission is not just about preserving flavor, but about upholding a worldview in which food is not a commodity but a cultural expression bound to place and practice.

His dream is that one day his children, or others inspired by his teachings, will take up the cause and continue the fermentation journey.

In a final, spiritual meditation, Custodians of Wonder introduces the centuries-old European custom of “telling the bees. ” This ritual, found in Celtic and Christian traditions, involves informing bees of major life events—births, deaths, marriages—so they may remain in harmony with the household.

Bees, seen as divine messengers or sacred beings, were thought to react emotionally to these changes. In medieval Christian thought, they symbolized purity and divine order, and their wax was considered the only acceptable candle material for religious ceremonies.

Alison Wakeman, a British beekeeper, revived the tradition after a chance inheritance of bees. Her emotional connection to the hives led her to inform them of family milestones, and she came to believe in the bees’ subtle responses.

Other beekeepers echo these sentiments, sharing stories of bees grieving or rejoicing in alignment with human events. Though science cannot prove bees understand these rituals, the practice remains a powerful metaphor for human connection with the natural world.

It reinforces our intuitive need to find kinship with creatures whose societies reflect our own values of community, order, and cooperation.

These interconnected stories in Custodians of Wonder portray people bound not by fame or wealth, but by responsibility—responsibility to a past that can only survive through memory, to a craft that only lives if practiced, and to a relationship with the natural world that demands care and reverence.

Whether sounding a horn in the snowy hours of a Swedish night, tending to bacteria in a barrel, or tapping the wooden keys of an ancient balafon, these individuals perform acts of devotion that tether us to our human essence: the desire to remember, to share, and to protect what matters most.

Characters

Balla Kouyaté

Balla Kouyaté stands as a deeply symbolic figure in Custodians of Wonder, embodying the resilience, continuity, and cultural depth of the Mandinka oral tradition. A direct descendant of the legendary griot Balla Fasséké, Balla’s life is intertwined with the preservation of a rich cultural legacy that stretches back to the Mali Empire.

His childhood in Bamako was defined by both physical adversity and profound cultural immersion. Though unable to walk until he was seven, Balla found empowerment through the balafon, the ancient xylophone-like instrument central to the Mandinka heritage.

Under his father’s guidance, he did not merely learn music—he inherited a sacred responsibility, one steeped in spiritual symbolism and historical memory.

The balafon itself becomes an extension of Balla’s identity, a relic of civilization that he is both heir to and steward of. His dedication to it is not performative but existential, anchoring him in a diasporic journey that saw him weather hardship as an undocumented immigrant in the United States.

His years of struggle—in convenience stores, car washes, and the margins of society—contrast starkly with the reverence his music now commands. Yet, these hardships sharpen his character, imbuing him with humility and tenacity.

Recognition by cultural institutions and collaboration with global artists reveal not just his talent but the power of tradition to transcend geography and time.

Balla’s character deepens through personal loss—most poignantly, the death of his wife, Kris. Her support, especially in his creative pursuits, underscores how personal relationships nourish cultural expression.

In honoring her memory through a family album and a return to West Africa with his children, Balla reaffirms his role not just as a griot, but as a father, husband, and cultural bridge. His life becomes a testament to the belief that oral history is not static; it evolves, migrating across continents and generations while retaining its emotional and spiritual core.

Whether or not he becomes the next balatigui, Balla Kouyaté has already fulfilled the griot’s most sacred function: to embody and transmit the living voice of a people.

Roland Borg

Roland Borg emerges as a quiet sentinel of tradition in Custodians of Wonder, his life an enduring testament to the sacred, if often invisible, labor of cultural guardianship. As the night watchman of Ystad, Sweden, Roland is both a literal and symbolic figure—a lone figure against the tide of modernization.

His nightly rounds and horn calls are more than ritual; they are emotional lifelines for a town that has grown to equate his presence with safety, continuity, and identity. His lineage, tracing back over a hundred years of night watchmen in the Borg family, positions him not merely as an individual but as a link in a familial and civic tradition that encapsulates the town’s historical memory.

Roland’s character is built on steadfastness, humility, and profound emotional resonance. Despite suffering a stroke, he persisted in his duties, reshaping his life to accommodate a responsibility he sees as sacred.

His relationship with Ystad is deeply personal—illustrated by small, poignant habits like phoning his wife Yvonne after each shift or watching the same Christmas movie year after year. These intimate rituals humanize him, revealing a man of great emotional sensitivity and loyalty.

His heroism, though understated, becomes apparent during the crisis of the Dawn Pyromaniac, when his vigilance helped protect the town. In that moment, Roland transcended the boundaries of tradition and became a modern-day protector.

Yet, Roland also carries the weight of looming loss. The uncertainty surrounding his succession—his own son choosing a different path—infuses his story with a quiet melancholy.

His dedication contrasts starkly with bureaucratic indifference, raising urgent questions about what happens when society loses its memory-keepers. Roland is not just a character but a cultural touchstone, proving that true tradition lies not in spectacle but in the quiet, persistent devotion to roles that make a place feel like home.

Yasuo Yamamoto

Yasuo Yamamoto, the soy sauce brewer from Shōdoshima, is a modern-day artisan-warrior in Custodians of Wonder, fighting to reclaim and preserve Japan’s endangered culinary soul. His story is a powerful reminder that heritage does not survive by accident—it requires choice, sacrifice, and passionate stewardship.

Yasuo is not simply preserving a recipe; he is resuscitating an entire worldview, one that sees fermentation as a dialogue between humans and nature. The barrels he uses—kioke—are more than tools; they are living ecosystems, repositories of bacterial life that reflect centuries of culinary evolution and spiritual harmony.

Yasuo’s transformation is central to his character. He began as a member of Japan’s consumer-driven workforce, selling products he didn’t believe in.

His decision to return to his family’s brewery marks a profound rupture with convenience and profitability in favor of authenticity and reverence. In recommitting to the ancient, four-year fermentation process, he reclaims not just a lost art, but a national identity increasingly threatened by industrial homogenization.

His work is meticulous and philosophical, informed by a deep respect for microbial life and an almost spiritual understanding of fermentation as symbiosis.

What sets Yasuo apart is his blend of tradition and activism. Recognizing that revival requires outreach, he becomes a teacher, builder, and evangelist for kioke brewing.

His efforts to train others and increase global demand for traditional shoyu reflect a rare mix of humility and vision. Even as he battles demographic decline and economic pressures, Yasuo maintains an almost monastic discipline, driven by the belief that food—real food—is culture’s deepest expression.

Through him, we see that preservation is not nostalgia; it is resistance against erasure and a courageous stand for craftsmanship in a world of shortcuts.

Alison Wakeman

Alison Wakeman’s character in Custodians of Wonder reflects a deeply personal, mystical relationship between human life and the natural world. Unlike the other protagonists, Alison did not inherit her role as a custodian—she stumbled into it, acquiring her first beehive by chance.

Yet it is precisely this unplanned beginning that makes her journey so poignant. Her initial curiosity evolves into a profound spiritual bond with her bees, one shaped by the age-old tradition of “telling the bees.” In embracing this ritual, Alison steps into an ancient lineage of folk wisdom, becoming not just a beekeeper but a participant in a metaphysical dialogue with the nonhuman world.

Alison’s character is marked by sensitivity, intuition, and reverence. Her instinct to communicate with her bees during family milestones—deaths, births, marriages—is not driven by superstition but by emotional truth.

She experiences their reactions as subtle affirmations, whether or not science agrees. This sensibility places her within a broader continuum of wisdom-keepers, people who understand that tradition is as much about feeling as it is about fact.

Her story also expands through shared experiences with other beekeepers who describe similar uncanny interactions, reinforcing the idea that these connections, while unverifiable, are deeply human.

Through Alison, the book explores the theme of kinship with nature. Her relationship with bees represents a form of ecological empathy, a response to the increasingly urgent need to reconnect with the living world.

In a time when bee populations are threatened by environmental degradation, her practice gains additional gravity. She symbolizes the quiet power of individual actions rooted in love and ritual, demonstrating that ancient traditions—far from irrelevant—can offer profound spiritual and ecological insights in the modern world.

Themes

Cultural Custodianship and the Fragility of Tradition

Across the narratives in Custodians of Wonder, a recurring theme is the precarious yet powerful role of individuals as vessels of cultural preservation. Balla Kouyaté’s inheritance of the griot tradition, Roland Borg’s nightly vigil as Ystad’s watchman, and Yasuo Yamamoto’s resistance to industrialized fermentation all illustrate how singular people, often without institutional backing, sustain ancient practices in the face of rapid modernization.

These individuals act not just as bearers of customs but as active agents keeping fragile legacies alive through personal devotion. Their work is often thankless and sustained by emotional ties, spiritual reverence, or familial obligation rather than economic incentives.

This cultural custodianship is not institutionalized or systematically ensured; it relies on intimate commitment and the sense that some things are too sacred to abandon. The griot’s oral memory, the night watchman’s horn, and the bacteria-laden barrels are living archives, each encoded with stories, rituals, and identities that are not reproducible by technology or textbooks.

The fragility of these practices underscores how easily traditions can vanish—not because they are obsolete, but because they lack successors willing or able to bear their weight. This theme asks a pressing question: what happens when a custodian dies without a disciple?

Whether in Mali, Sweden, or Japan, the future of these traditions rests on the unpredictable convergence of devotion, serendipity, and generational transmission.

Identity, Resilience, and the Immigrant Experience

Balla Kouyaté’s life story offers a deeply layered exploration of how cultural identity is preserved, adapted, and reasserted in exile. His journey from Bamako to the United States mirrors the tension many immigrants face between economic survival and cultural authenticity.

His early years as an undocumented worker reveal the compromises often demanded by migration, but his secret practice of the balafon amid hardship affirms the role of art as a means of anchoring oneself in unfamiliar territory. Balla’s story is not one of assimilation but of reclamation—of refusing to abandon the rhythms, melodies, and meanings of his lineage even when those around him failed to understand them.

The emotional and spiritual support of his wife Kris, and his eventual recognition through artistic collaborations, mark the moments when personal endurance transforms into cultural affirmation. His return to Mali with his children is not simply nostalgic; it is restorative.

It signifies the need for diasporic identities to reconnect with ancestral spaces to heal the dissonance created by dislocation. This theme highlights how resilience is not only about enduring hardship, but about preserving one’s roots and transmitting them through new languages, spaces, and generations.

Sacredness of Ritual in Everyday Life

The tradition of “telling the bees” captures how rituals—regardless of empirical validity—serve as deeply meaningful conduits of emotional, spiritual, and ecological connection. This theme extends across multiple stories in Custodians of Wonder, emphasizing that rituals are not superstitions to be discarded in modernity but practices of communion, empathy, and respect.

In Wakeman’s beekeeping, informing the hive of life’s milestones becomes a dialogue between species, an act of honoring the bees’ role as participants in the household’s continuity. These gestures, seemingly quaint, reflect an enduring belief in the sentience and sacredness of non-human life.

Similarly, Yamamoto’s reverence for his fermenting microbes echoes a spiritual relationship with nature, where even bacteria are understood as collaborators in creation. Roland’s nightly horn calls, too, function as a ritual of assurance—not merely auditory signals, but emotional beacons that connect individuals to place and time.

These practices resist the logic of efficiency and instrumentalism. Instead, they remind us that continuity, comfort, and connection often hinge on repetitive, symbolic acts that defy commodification.

In a world of growing detachment and ecological crisis, these rituals represent an alternative ethos—one where reverence supersedes rationalism and where storytelling, music, fermentation, and ceremony are not only cultural artifacts but essential ways of being.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Memory and Legacy

Each narrative in Custodians of Wonder examines the theme of generational continuity—not as a linear handoff but as a fragile, intentional act. Memory, in these stories, is not preserved through archives or digital files, but through bodies, voices, and tools passed down within families or tight-knit communities.

Balla Kouyaté’s training under his father, Roland Borg’s inherited call, and Yamamoto’s efforts to rebuild kioke all involve deliberate acts of transmission, often made difficult by modern ruptures. These are not smooth inheritances; they are contested, complicated, and sometimes interrupted.

The possibility of discontinuity looms large, especially when younger generations migrate, modernize, or lose interest. Roland’s son, for example, has chosen a different path, leaving the future of Ystad’s watch in question.

Yamamoto’s children have not yet committed to the craft, and the craft itself verges on extinction. These uncertainties reflect the tension between preserving the past and adapting to the present.

The emotional weight of legacy is palpable: it is a burden and a blessing, an act of love and of labor. Whether through the notes of a balafon, the taste of real soy sauce, or the call from a watchtower, the stories suggest that memory is not static—it must be continually reanimated by those willing to carry its flame forward.

The Conflict Between Modern Efficiency and Traditional Knowledge

One of the book’s most persistent tensions lies in the friction between mechanized progress and inherited expertise. Yamamoto’s rejection of industrialized soy sauce production embodies this conflict most starkly.

The abandonment of kioke barrels in favor of steel tanks mirrors a broader global pattern in which speed, uniformity, and cost-efficiency supplant quality, depth, and ecological harmony. Similar dynamics appear in Balla’s early experience in America, where his musical heritage holds no immediate utility in the gig economy, and in Ystad, where digital surveillance and modern security systems threaten to render the watchman obsolete.

Yet, what is lost in these transformations is not only aesthetic or sentimental—it is epistemological. Traditional knowledge is grounded in patient observation, lived experience, and intimate relationships with materials, people, and ecosystems.

It is not scalable, and that is its strength and its vulnerability. The book illustrates that modern systems often overlook these forms of wisdom because they do not produce easily quantifiable outputs.

However, the stories argue that these traditions offer something enduring: they root people in time and place, provide continuity across generations, and foster ethical relationships with the world. In resisting modern efficiency, these custodians are not resisting change—they are resisting erasure.

Their work is a form of dissent, a refusal to allow depth and meaning to be replaced by speed and convenience.