Daddy Issues by Kate Goldbeck Summary, Characters and Themes

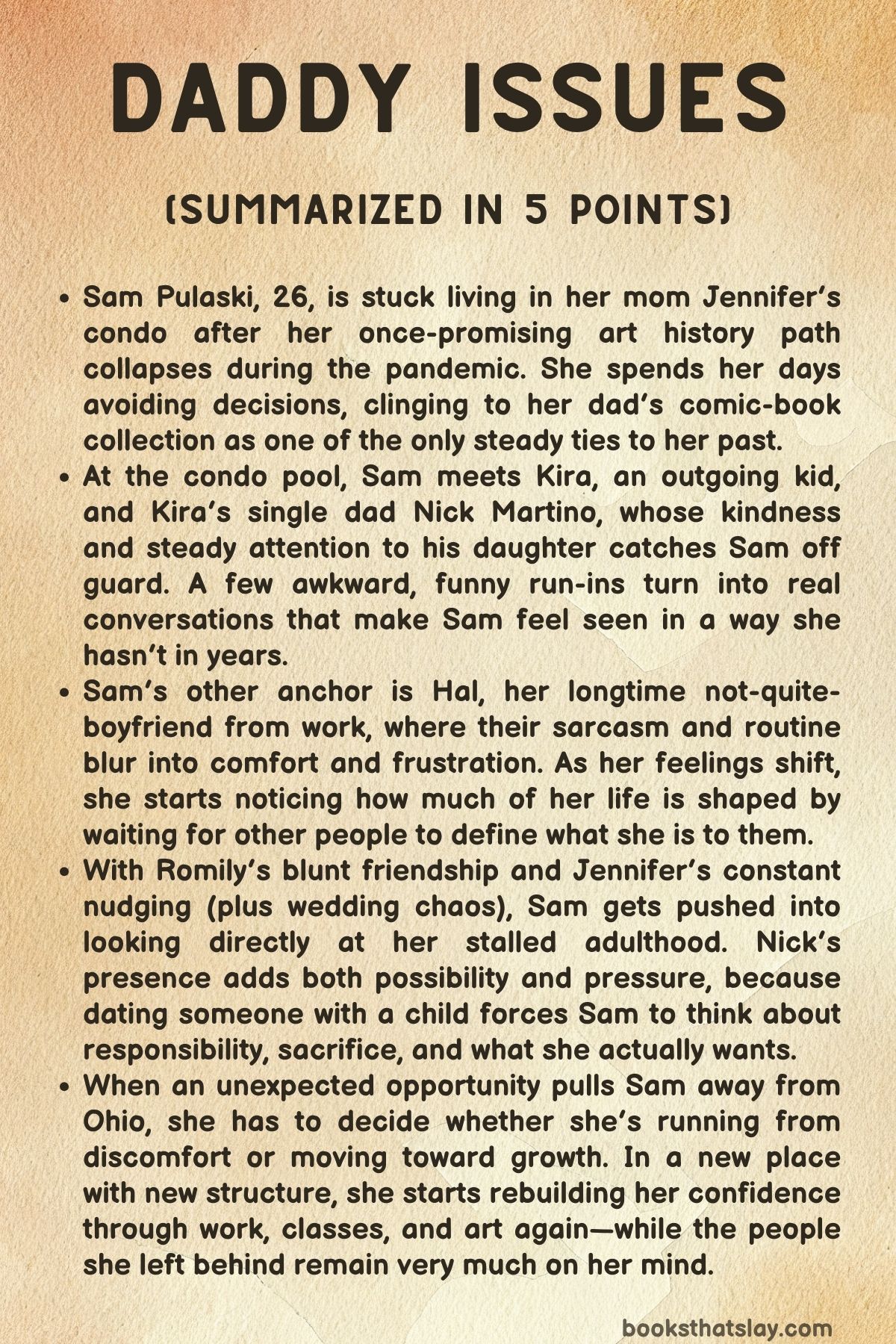

Daddy Issues by Kate Goldbeck is a sharp, modern romantic comedy about growing up when you’re already supposed to be grown. It follows Sam Pulaski, a once-promising art historian whose post-pandemic burnout has left her living with her mother, avoiding her future, and working at a tiki bar instead of in a museum.

When she meets Nick Martino—a charming single dad next door—their awkward, funny, and tender encounters challenge her cynicism and her fear of failure. Blending humor with emotional honesty, the novel explores family, love, and the messy process of finding direction after your plans collapse.

Summary

Sam Pulaski, a 26-year-old former art history student, lives in her mother Jennifer’s Ohio condo, sleeping in what used to be the home office. Once on track for an academic career in Italy, Sam’s ambitions unraveled during the pandemic, leaving her aimless and filled with self-doubt.

She spends her days scrolling through her phone and avoiding responsibility while her mother—kind but assertive—urges her to rebuild her career and social life. The only relic of her father, who left years ago, is his vast comic book collection, a lingering reminder of their brief connection through shared interests.

One day, the peace of her stagnant routine is disrupted by the noisy renovations of her new neighbor, whose hammering knocks her father’s comic boxes off the shelf. Not long after, Sam notices a father and daughter at the condo’s pool—Nick Martino and his lively daughter Kira.

Nick’s patient, kind parenting stands out amid the chaos of the pool’s usual crowd. Kira draws Sam into her imaginative games, and an awkward but endearing bond forms between them.

Nick’s warmth and humor intrigue Sam, though she brushes it off as harmless curiosity.

Sam’s own life feels frozen in comparison. Once a promising academic, she now bartends at the kitschy Lōkahi Lounge with Hal, a sarcastic ex–MFA student who has been her on-and-off lover for years.

Their relationship blurs the line between friendship and romance, sustained by banter and routine but marked by emotional stalemate. Despite her attraction to Hal, Sam realizes their connection offers no growth—just familiarity and avoidance.

When her mother’s contractor arrives to remodel the condo, Sam discovers that the man drilling next door is none other than Nick—the single dad from the pool. Their surprise recognition sparks awkward humor, mutual teasing, and subtle curiosity.

Nick, who recently moved in with Kira after his divorce, becomes an increasingly visible presence in Sam’s orbit. Her mother, meanwhile, takes an immediate liking to him and begins her own quiet matchmaking campaign, much to Sam’s embarrassment.

A series of comedic and revealing interactions follows. Sam and her friend Romily, a pragmatic data enthusiast, get locked out of the condo and end up taking shelter in Nick’s apartment.

Over pizza and small talk, Sam observes Nick’s world—a mix of single-parent exhaustion and steady affection. Kira’s boundless imagination and Nick’s gentle patience create a warmth that draws Sam in.

The evening evolves into a surprisingly intimate conversation between Sam and Nick about art, family, and the ways they’ve both lost parts of themselves over time.

At work and in her personal life, Sam continues to wrestle with her stalled ambitions and the absence of a clear identity. Her relationship with Hal frays further as she begins to see its limits.

Nick, in contrast, begins to occupy her thoughts—his humor, steadiness, and openness stirring something she hadn’t realized she missed.

Their connection deepens through a mix of humor and vulnerability. After an evening of flirtation that becomes physically intimate, Sam abruptly pulls away, overwhelmed and emotionally unprepared.

Nick’s response—gentle understanding rather than frustration—reveals his depth and solidifies their trust. Yet, complications multiply when Sam’s mother invites Nick and Kira to her wedding and simultaneously attempts to set Nick up with another woman, intensifying Sam’s confusion and jealousy.

As Sam distances herself from Hal and begins confronting her emotional patterns, her bond with Nick strengthens. They spend more time together—sharing meals, teaching her to drive, and exchanging small confidences that reveal how much they’ve both been hiding.

Nick admits to the guilt and limitations of single fatherhood, while Sam acknowledges her fears of failure and dependence. Their humor and shared pop culture references, from Star Trek to comic books, become a language of connection.

Their relationship turns romantic in earnest after a series of near misses and emotional breakthroughs. Sam meets Kira again, this time seeing firsthand how deeply Nick loves his daughter.

They navigate small joys and big fears—watching fireworks, cooking breakfast, and discussing the responsibilities that tie Nick to Ohio. When they finally sleep together, it feels like a moment of growth and mutual healing rather than escape.

But just as Sam begins to rediscover purpose, she receives an offer for a temporary college job in upstate New York. The opportunity reignites her old ambition but also threatens her newfound stability with Nick.

When she tells him, he insists he can’t ask her to stay—his priority is Kira, and he refuses to be the reason Sam sacrifices her independence. Hurt but understanding, Sam demands closure rather than lingering hope, and they part ways.

Sam leaves Ohio to start over. In New York, she rents a cramped room and begins her administrative job at a college, surprised to find comfort in the structure.

On impulse, she joins a drawing class and rediscovers her creative spark, reconnecting with the passion she buried years ago. Through the process, she rebuilds confidence and a sense of self, learning to define success on her own terms.

She also gets her driver’s license—something Nick once helped her practice for—signaling her growing independence.

Months later, she meets Hal again in New York. Their conversation, once charged with unspoken longing, now feels easy and resolved.

They part as friends, marking another quiet sign of Sam’s maturity. Eventually, she returns to Ohio, moving in with Romily and confronting her past.

Sorting through her father’s old comics, she decides to finally let go of his storage unit, symbolically releasing the weight of her childhood.

When Kira reaches out for help after an embarrassing moment at parkour class, Sam rushes to her side without hesitation. She comforts Kira, helps her through the crisis, and leaves behind her phone by accident—only for Kira to use it to write a note: “My dad really loves you.” Outside, Nick arrives to pick Kira up, and he and Sam finally face each other again.

They talk honestly about what’s changed—Sam’s new sense of direction, Nick’s ongoing divorce, and their lingering love. Both admit they still want to be part of each other’s lives.

The novel ends with a reunion filled with humor and hope. Sam tells Nick she’s ready to build a life, not as someone waiting to be rescued but as someone choosing what matters.

He invites her to Christmas Eve dinner with Kira and promises that this time, he isn’t going anywhere. Their reconnection isn’t dramatic but grounded—two people meeting again after finding themselves.

As they plan to see each other the next night, the story closes with a sense of renewal and quiet joy, showing that love, like art, is a work in progress.

Characters

Sam Pulaski

Sam Pulaski is the emotional center of Daddy Issues and the character through whom the book examines stalled adulthood, shame, and the long tail of parental absence. At twenty-six, she looks “old enough” to be stable but feels developmentally stuck, and the narrative makes that stuckness physical: sleeping on a daybed in her mother’s home office, hiding behind late mornings and doomscrolling, and carrying her father’s comic boxes like both heirloom and burden.

Sam’s intelligence and past achievement are real, which is why her collapse hits hard; she has proof she once moved through the world with direction, but the pandemic becomes the event she uses to explain everything that happened afterward, even when her deeper fear is that she will never be “special” again. Her desire is complicated because it is split between wanting to be chosen and wanting to choose herself.

With Hal, she accepts ambiguity to avoid the risk of asking for more; with Nick, she risks wanting something that has consequences. Sam’s arc is not simply romantic or careerist, but about rebuilding agency: she learns to tolerate discomfort, say what she wants out loud, and treat structure as care rather than punishment.

Her return to drawing is the clearest symbol of reclamation, because it reconnects her to the version of herself her father once praised, without requiring his presence or approval to validate it. By the end, Sam’s growth looks less like a single triumphant breakthrough and more like steady, unglamorous self-respect—getting a license, taking a job that works, setting boundaries, and choosing relationships where she can be fully present.

Nick Martino

Nick Martino initially enters as an object of fascination—an attentive father at the pool who contrasts with the scene’s aimless adults—but he quickly becomes a moral counterweight to Sam’s drift. He is warm, funny, and flirtatious, yet his defining trait is a kind of disciplined devotion: his life is arranged around Kira, and that priority isn’t performative.

Nick’s appeal lies in the way he holds steadiness and messiness together; he has boxes, collectibles, and exhaustion, but he still shows up with consistency, patience, and a willingness to talk things through when Sam dissociates during intimacy. That moment reveals the most important part of his character: he does not push past a boundary for his own gratification, and he doesn’t punish vulnerability with sulking or withdrawal.

At the same time, Nick’s ethics create conflict. When Sam faces the job opportunity, he refuses to “fight” for her in the way she craves because he believes asking her to sacrifice would be selfish, especially after hearing Jennifer’s concerns.

This makes him both admirable and frustrating: his sense of duty is genuine love, but it also becomes a shield that keeps him from articulating his own needs. His later move to finalize the divorce suggests maturation on his side too—choosing clarity over limbo—so the reunion doesn’t feel like a reset, but like a better-timed version of the relationship, one where he can be present without asking Sam to shrink and where Sam can return by choice rather than by drift.

Kira Martino

Kira is not just a “cute kid” catalyst for romance; she’s a character with agency who pressures the adults into honesty by existing loudly, curiously, and without embarrassment. Her imagination—pool games, drawings, invented hybrid-animal characters—mirrors Sam’s buried creativity, and their bond gives Sam a pathway into caretaking without requiring Sam to suddenly want motherhood.

Kira’s precocity also exposes adult awkwardness, especially around sexual language and the accidental “furries” conversation, but the book uses those moments to show what kind of adults these people are: Kira is resilient and adaptable, and Nick responds with humor instead of shame, which teaches Sam that care can be light rather than heavy. The fireworks scare is crucial for understanding Kira’s role in Nick’s life and, by extension, the stakes of dating him; when she disappears, Nick’s panic makes the parental bond undeniable, and Sam has to reckon with what it means to love someone whose first loyalty must always be a child.

Kira’s period crisis later becomes the most intimate proof of trust: she reaches for Sam in a moment of fear and humiliation, and Sam responds competently, tenderly, and fast. That scene is a turning point because it’s where Sam realizes she can be steady for someone else, and where Kira, in her blunt sincerity, effectively tells the truth the adults are scared to say.

Jennifer Pulaski

Jennifer is a parent who loves her daughter but doesn’t always know how to love without managing. She provides housing, encouragement, and patience, yet her support often comes with a gentle pressure that becomes suffocating because it touches Sam’s most sensitive wound: wasted potential.

Jennifer’s personality—warm, social, a little too comfortable oversharing—creates much of the comedy and mortification, but underneath that is a believable parental anxiety. She wants Sam safe, stable, and moving, and she mistakes nudging for helping.

Her matchmaking behavior with Nick, and her impulse to narrate Sam’s quirks in front of him, reveal a boundary problem that isn’t malicious so much as habitual; Jennifer treats her adult daughter like a project she can talk into flourishing. Her engagement to Perry also forces a family transition: Jennifer is building a new life stage while Sam is stuck in an old one, which intensifies Sam’s sense of being left behind.

The later frank conversation between mother and daughter is important because Jennifer’s arc is learning that love is not the same as steering. She doesn’t stop caring, but she starts listening differently—making space for Sam’s slower, self-directed rebuild rather than trying to push her into a life that looks correct from the outside.

Perry

Perry functions as a quietly stabilizing presence and a surprising mirror to Nick. Where Nick embodies devoted parenthood, Perry represents an honest alternative: someone who does not want kids and does not pretend otherwise.

That honesty could read as cold, but in context it becomes a kind of integrity; Perry isn’t cruel to Sam, and their bond grows through straightforward, low-drama support like driving her to the BMV and celebrating her permit. Perry’s admission about finding other people’s kids irritating complicates Sam’s romantic calculus because it highlights that “family” can be built in different configurations, and that being good to someone does not require having parental instincts.

Perry also models what it looks like to enter a family as an outsider with care. At the airport, Perry’s willingness to name insecurity, seek information, and reassure Sam that she is not an interloper gives Sam something her father never provided: a reliable adult who shows up without making her earn it.

Perry’s role is less about romance and more about demonstrating that commitment can be practical, present, and chosen—especially for someone who has spent years chasing affection that stayed ambiguous.

Hal

Hal is the relationship that teaches Sam how easy it is to confuse intimacy with progress. He is witty, charismatic, and emotionally withholding in a way that can look like cool detachment but functions like a trap: Sam keeps orbiting him because he gives her enough closeness to feel wanted while avoiding the vulnerability of definition.

Their origin story—him defending her at a comic store and getting fired—makes Hal feel like someone who “sees” her, and their shared humor turns monotonous work into a private world, which is why the attachment lasts. Yet Hal’s affection often arrives wrapped in jokes that undercut seriousness, and the line about head scratches being “better than sex” lands as a perfect summary of his emotional stance: he enjoys comfort, but on terms that keep him safe and unaccountable.

Hal is not painted as a villain; he is another stalled person whose talent and cynicism mask fear. What changes is Sam’s tolerance.

Blocking him is less revenge than a declaration that she will no longer interpret vagueness as depth. When they meet again later, the softness in their goodbye suggests Hal mattered, but in a way that belongs to a past version of Sam—someone who accepted uncertainty because certainty felt too risky to request.

Romily

Romily is the story’s analytical conscience, translating messy feelings into frameworks without stripping them of meaning. Her bluntness can feel abrasive, but it’s a form of care that suits Sam, because Sam’s problem is not a lack of insight—it’s avoidance—and Romily refuses to let avoidance masquerade as sophistication.

The PowerPoint party concept and the “casual continuum” are comedic on the surface, but they reveal Romily’s deeper role: she gives Sam language for patterns Sam already senses, especially the way “nonexclusive” arrangements can become holding pens for people who are afraid to ask for more. Romily also balances head and heart; she warns Sam about dating a single parent not to judge Nick or Kira, but to force Sam to acknowledge the real constraints involved.

Importantly, Romily doesn’t “solve” Sam. She stays present through embarrassing moments like getting locked out, through spirals, and through the long aftermath when Sam returns to Columbus and they live together.

In a book obsessed with parental bonds, Romily is chosen family: steady, unsentimental, and there when Sam needs a witness to her growth.

Shawna

Shawna mostly appears as possibility rather than person, and that is exactly her narrative function. She is the “reasonable match” Jennifer tries to engineer for Nick, representing the way other adults attempt to tidy complicated feelings into socially acceptable pairings.

For Sam, Shawna triggers jealousy and humiliation because she forces Sam to confront that she wants Nick, and she wants to be wanted back, not just liked. Nick’s response—that Shawna messaged him but he hasn’t met her—also clarifies his character; he is open to moving forward but not easily swept into someone else’s plan.

Shawna’s limited presence underscores a key theme: the story isn’t a love triangle, it’s a test of whether Sam will name her desire instead of hiding behind plausible deniability.

Peggy

Peggy is a late-arriving but pivotal figure because she offers Sam something Sam has been missing since her academic path collapsed: a mentor who makes creativity feel accessible rather than evaluative. Peggy’s teaching style—playful prompts, childlike materials, an insistence that everyone belongs—directly counters the perfectionism that shut Sam down after that college art grade.

Where Sam’s earlier world rewarded prestige, specialization, and gatekeeping, Peggy’s classroom rewards mess, experimentation, and showing up. The impact is practical: Sam draws again, fills notebooks, invents characters, and rebuilds a relationship to art that is about expression rather than proof.

Peggy’s role highlights that Sam’s healing is not only romantic; it is also pedagogical and communal, rooted in environments that invite her back into herself.

Christina

Christina is present only through reference, but she embodies the social ecosystem Jennifer inhabits: friends who trade life updates, marriages, divorces, and eligible singles like they are logistics. By being the conduit through which Shawna is introduced, Christina represents the external pressure of “normal adult timelines” that Sam feels judged by.

Even without much page-time in the summary, Christina’s existence matters because it shows how easily Sam’s private uncertainty becomes public conversation among well-meaning adults, intensifying Sam’s shame and making her feel observed in her own home.

Themes

Stalled Adulthood and the Aftermath of Disrupted Plans

Sam’s life is defined by the gap between who she expected to become and the person she can currently tolerate being. Living in her mother’s condo, sleeping on a daybed in what used to be a home office, and waking into cycles of doomscrolling and avoidance, she carries a constant awareness that time is passing while she stays still.

The collapse of her academic path after the pandemic isn’t treated as a single event that ended something; it becomes a long echo that keeps rewriting her self-image year after year. What makes the stagnation painful is that Sam has receipts of competence—internships, research, papers, professional proximity to serious art—yet those achievements feel like artifacts from a different life rather than proof she can rebuild.

That mismatch feeds shame, and shame feeds inertia. Even her job at Lōkahi Lounge functions as a kind of holding pattern: it pays, it numbs, it provides a familiar stage for jokes and small rebellions, but it doesn’t offer a narrative of growth that she can believe in.

Around her, adulthood is moving forward through other people’s milestones: her mother’s engagement, Perry’s steady presence, Nick’s daily parenting responsibilities. Those lives make Sam’s drift more obvious, which is why she both resents and needs the pressure to “get it together.” The story shows stagnation not as laziness but as a protective response—if she doesn’t try, she can’t fail again in public.

That’s also why small steps carry such weight: a learner’s permit, a temporary job, auditing a class, filling notebooks with messy drawings. These choices aren’t framed as sudden transformation; they are proof that structure can be kinder than freedom when freedom is contaminated by fear.

Fathers, Abandonment, and the Complicated Hunger to Be Chosen

Sam’s relationship with her father is less a relationship than a lingering wound with a collectible label stuck to it. The comic collection he left her is both a gift and an emotional anchor: it’s tangible proof he once shared time with her, praised her, and treated her interests as special, but it also becomes a substitute for actual presence.

The book studies how abandonment can create a strange kind of loyalty, where the child keeps tending the remaining objects as if care can reverse the original leaving. Sam holds on to those boxes not only because they matter to her identity, but because letting go would mean admitting that the bond is mostly memory and hope.

Her father’s early “prodigy” praise also lands as a trap: it teaches her that love and attention arrive when she performs exceptionalism. When she receives a disappointing grade in college art, she doesn’t just change majors; she changes the rules for how she can be acceptable.

Art history becomes safer because it offers external validation and clearer metrics, but it also moves her away from the vulnerable act of making. Nick’s presence as a devoted father intensifies this theme by providing a living contrast.

Watching him with Kira, Sam is confronted by what she didn’t get: consistency, attentiveness, and a parent whose instincts are anchored in the child’s needs. That contrast produces admiration, jealousy, tenderness, and grief all at once, especially during the fireworks incident when Nick’s panic reveals how deeply he is bonded to his daughter.

The story also widens the idea of “dad issues” beyond biology by showing Perry learning the emotional labor of stepping into a parental role without pretending it’s simple. The airport conversation with Perry matters because it offers Sam something her father never did: someone showing up at the hard moment, naming their uncertainty, and staying anyway.

The blank father-daughter journal later becomes the final symbolic blow—an object meant to hold shared words that instead contains absence—pushing Sam toward the choice to stop subsidizing the fantasy of her father’s return.

Art, Creativity, and Reclaiming the Self After Shame

Sam’s creative identity isn’t lost because she lacks talent; it’s lost because creativity became entangled with judgment. Early on, drawing is linked to her father’s admiration and the warm certainty of being “special.” When academia and grading enter the picture, that certainty collapses into evaluation, and evaluation turns art into a place where she can be measured and found lacking.

Switching to art history allows her to remain near art while avoiding the vulnerability of producing it. That coping strategy works until her scholarly path collapses too, leaving her with both a broken plan and a broken relationship to the act that once gave her joy.

The turning point isn’t a triumphant return to mastery; it’s the permission to be messy without being punished for it. The class in the Hudson Valley, with its childlike materials and direct insistence that everyone belongs, reframes creativity as practice rather than proof.

Sam’s notebooks fill not because she suddenly becomes fearless but because repetition gives her a new kind of safety. Drawing becomes a private language for processing her life—characters based on people she knows, scenes that let her control the pacing, panels that hold what she can’t say out loud.

The book also uses comics as a philosophy of identity: Sam explains the “magic” between panels, the unseen moments the reader supplies. That idea maps onto her own life, where the most important changes happen in the quiet spaces—between a blocked number and a first honest conversation, between a breakup and a new routine, between wanting and choosing.

Even the comic collection shifts meaning over time. At first it is an inheritance loaded with longing; later it becomes something she can sell, sort, and handle as an adult with agency.

Reclaiming art is also reclaiming the right to change: she doesn’t have to be the “prodigy” child or the almost-PhD scholar to justify her existence. She can be someone who learns again, imperfectly, and still counts.

Intimacy, Consent, and the Body as a Site of Memory

The sexual and romantic moments in the story are never just about desire; they are about safety, agency, and how the body reacts when the mind is overloaded. The car scene with Nick is crucial because it refuses the common romance shortcut where chemistry overrides discomfort.

Sam’s dissociation interrupts the encounter, and the narrative treats that interruption as meaningful information rather than a hurdle to push through. Nick’s response—stopping, listening, and accepting her boundary without punishment—becomes a form of intimacy in itself.

It establishes a standard Sam hasn’t consistently experienced: that her “no” or “not now” does not threaten the relationship. This matters because Sam has spent years in a dynamic with Hal where emotional needs are minimized through humor and ambiguity.

With Hal, closeness exists, but it isn’t named; sex and comfort happen, but commitment remains out of reach, which trains Sam to accept partial forms of care. In contrast, Nick’s patience allows Sam to stay present later when she chooses sex on her own terms, after the Bundt cake gesture and the sense that she is seen as a whole person rather than a convenient companion.

The book also connects sexuality to control and self-worth. Sam’s jealousy when her mother tries to set Nick up with Shawna isn’t only romantic; it’s the old panic of being replaceable.

Her demand for a clean break later is similarly bodily—she wants certainty because uncertainty keeps her nervous system locked in waiting. Even her mention of a past abortion is presented as part of a larger conversation about choice and maternal expectation.

She doesn’t romanticize motherhood or treat it as inevitable; she names her reality and lets it coexist with her affection for Kira. Overall, intimacy here is built through accountability: communicating overstimulation, tolerating awkwardness, refusing to use sex as proof of value, and learning that desire can be mutual without being coercive.

Situationships, Emotional Avoidance, and the Cost of Unnamed Relationships

Sam and Hal’s long-running “more than a fling but never defined” relationship shows how ambiguity can become a lifestyle rather than a transitional phase. Their bond is real—shared humor, familiarity, a private world of routines and jokes—and that reality is exactly what makes the non-commitment feel confusing rather than straightforward.

The book portrays how situationships often persist not because nobody cares, but because caring is safer when it can be denied. Hal’s emotional detachment isn’t villainized; it’s presented as a pattern that benefits him by preserving independence and benefits Sam by providing closeness without forcing her to risk rejection through asking for more.

But the benefit rots over time. Sam’s growing discomfort surfaces in small stings, like the comment that her head scratches are “better than sex,” which reads as affectionate until it quietly places her in a role: soothing, convenient, not requiring reciprocity.

Romily’s PowerPoint and later “casual continuum” framing gives Sam language for what she’s living—how people can get stuck in a middle zone where the relationship has the emotional consequences of dating without the protections of dating. Language matters because unnamed relationships allow each person to rewrite the meaning of events in their favor.

Sam blocking Hal is a small act with big symbolic weight: it is her choosing clarity over habitual access. Importantly, the story doesn’t suggest that commitment automatically equals happiness.

Instead, it shows that the refusal to define things can become a way of avoiding accountability. When Sam starts something with Nick, she becomes more aware of how much she has been settling for.

Nick asks direct questions, makes explicit plans, and takes her seriously enough to be honest about constraints. That directness highlights how much emotional energy Sam spent interpreting Hal’s ambiguity.

The eventual meeting with Hal in New York provides closure without revenge; they acknowledge what they were to each other and separate without the earlier desperation. The theme lands on the idea that adulthood often requires grieving the comfort of half-relationships, because even the wrong closeness can feel better than the fear of being alone.

Parenting, Stepparent Anxiety, and Learning to Care Without Claiming Ownership

Nick’s identity as a father isn’t background detail; it is the central reality that shapes every romantic possibility in the story. Kira is not an obstacle written to create cute scenes; she is a full person whose needs set the ethical boundaries of the adults’ choices.

Nick’s parenting is shown in ordinary moments—pizza offers, bedtime routines, patient explanations—as well as in crisis, like the fireworks panic when Kira goes missing. That panic reveals the intensity of parental attachment and the particular kind of fear that comes with responsibility you can’t set down.

For Sam, witnessing that bond is both moving and destabilizing. She is drawn to Nick partly because he represents steadiness and care, but being close to that care forces her to confront what she didn’t receive from her own father.

It also brings up the question of what role she is allowed to have in Kira’s life. Sam’s anxiety after reading online forums about dating a single parent captures the cultural noise around stepmother narratives: the warnings, stereotypes, and horror stories that turn love into a risk assessment.

The book doesn’t argue that these fears are irrational; it shows how easily public stories can colonize private hope. Perry’s airport conversation adds another layer by addressing stepparent uncertainty directly.

Perry admits to seeking guidance, worrying about being an interloper, and trying to approach the role with care. That honesty models a kind of family-building that isn’t based on entitlement.

Sam’s eventual moment of caregiving—helping Kira during her first period—becomes the clearest demonstration of earned trust. She acts quickly, practically, and gently, not to “win” Nick but because Kira needs an adult who won’t shame her.

Kira’s note, “My dad really loves you,” matters because it frames Sam’s place as something Kira can perceive and endorse, not something Sam seizes. When Sam and Nick reunite, it’s with the understanding that love here includes a child, schedules, and patience.

Care becomes a practice: showing up, respecting the parent-child bond, and choosing commitment that doesn’t erase anyone else’s needs.