Days at the Morisaki Bookshop Summary, Characters and Themes

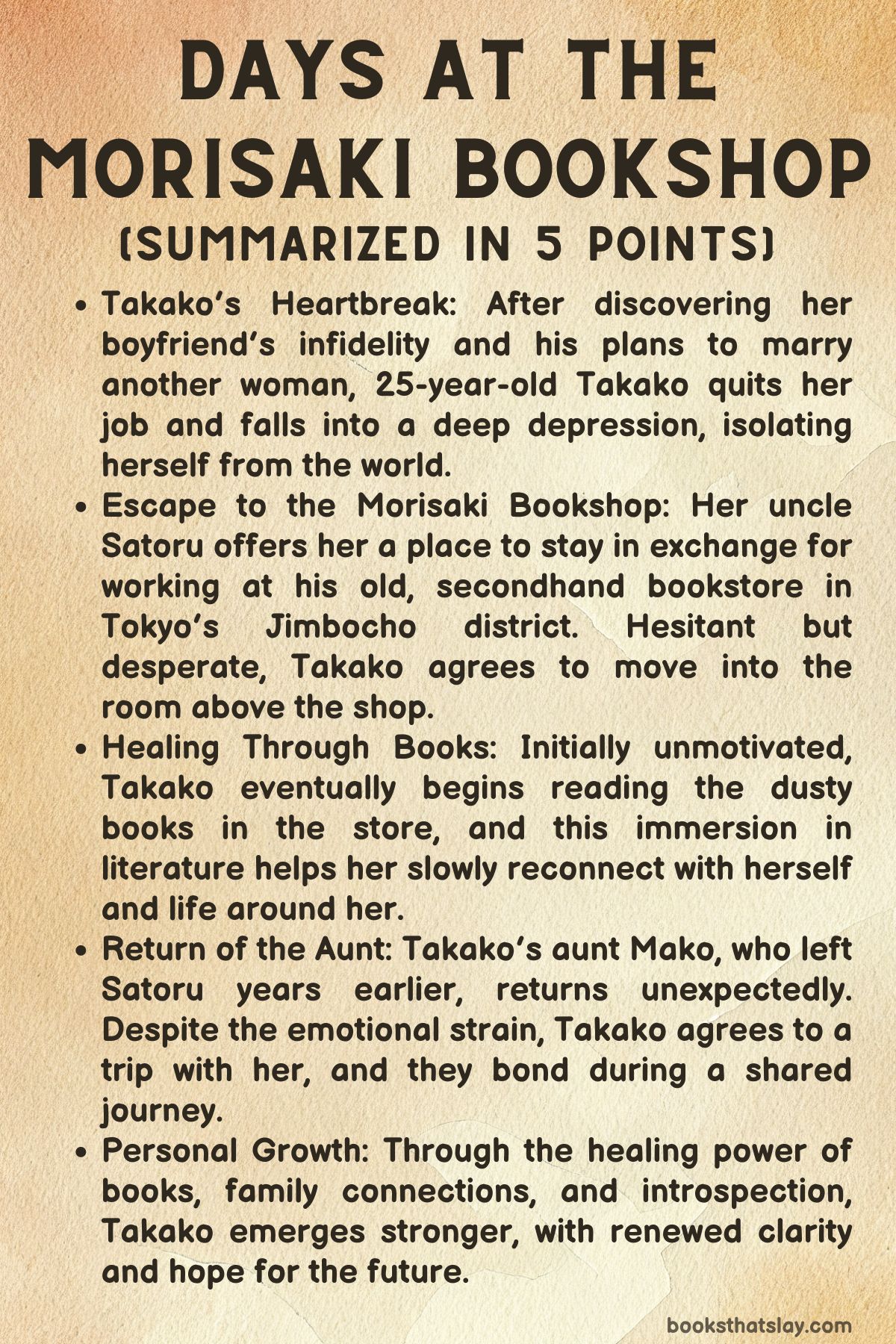

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop by Satoshi Yagisawa is a heartwarming, introspective novel about personal growth, family connections, and the solace of books. Set in Tokyo’s charming Jimbocho district, famous for its secondhand bookstores, the story follows a young woman named Takako who, after facing personal heartbreak, seeks refuge at her uncle’s bookshop.

What starts as a reluctant escape turns into a journey of rediscovery as she rebuilds her life through literature, relationships, and quiet moments of reflection. With its simple yet profound storytelling, this short novel offers a touching escape for anyone looking to be enveloped in warmth and introspection.

Summary

Takako, a 25-year-old woman, is hit hard by life when she learns that her boyfriend—a colleague at her office—has been seeing someone else and plans to marry her.

This news sends Takako into a downward spiral. Struggling with the weight of heartbreak and betrayal, she quits her job and withdraws from the world, spending her days in a haze of sadness and inactivity.

With no motivation or direction, she isolates herself in her apartment, feeling stuck in a deep emotional rut.

Out of nowhere, she receives an unexpected call from her uncle, Satoru, a man she hasn’t been particularly close to.

Satoru owns an old family bookstore, the Morisaki Bookshop, located in the Jimbocho district of Tokyo, a place renowned for its many secondhand bookstores. He offers her a lifeline of sorts: move into the room above his shop for free, and in exchange, help out with running the place.

Though initially hesitant and unsure if this will pull her out of her depressive slump, Takako eventually agrees. The prospect of reducing her living costs and the idea of a change of scenery push her toward the decision.

When Takako arrives, she is struck by the musty, almost forgotten quality of the bookshop. The place is cluttered with old, dusty books that seem to reflect the stagnant nature of her own life.

Her uncle, Satoru, is an eccentric yet kindhearted man with his own emotional baggage—he was left heartbroken when his wife, Mako, walked out on him five years earlier. Despite the gloominess of the setting, the bookshop slowly begins to weave its magic around Takako.

Initially, she spends her days aimlessly, watching time slip by. But as the weeks pass, Takako starts picking up random books from the shelves, immersing herself in their stories. This habit of reading gradually becomes her anchor.

Through the books, she begins to rediscover herself. Each story she dives into allows her to reflect on her own situation and slowly pulls her out of her emotional fog. As she begins to interact more with the bookstore’s regular customers and other characters around Jimbocho, she reconnects with life.

She forms new relationships, and a subtle shift takes place—she begins to heal.

However, the narrative doesn’t end there. Just as Takako starts feeling stable again, her aunt Mako, the very woman who abandoned Satoru, reappears.

Mako proposes an impromptu trip, and though Takako is initially unsure about reconnecting with her, she eventually agrees to the journey.

The two women set off on a hike, staying in a quiet tea house nestled in the mountains. During this trip, Takako learns about the complexities of Mako’s life and her reasons for leaving. What begins as an awkward reunion turns into a chance for emotional healing.

Mako’s return and her revelations give both Takako and Satoru an opportunity for closure, and the novel concludes on a note of quiet optimism, with Takako emerging stronger and more in tune with herself.

In its essence, Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is a tale of finding solace in unexpected places—whether it’s within the pages of a book or the bonds of family.

Through the simple beauty of everyday life, it reminds us that healing is often a slow, yet profoundly transformative process.

Characters

Takako

Takako, the central protagonist of the story, is a 25-year-old woman in a state of emotional and personal crisis at the beginning of the novel. Her character is initially portrayed as deeply wounded, having been betrayed by her lover, who not only was unfaithful but also plans to marry another woman.

This betrayal leaves Takako in a state of depression, marked by her withdrawal from daily life and her job. Her early portrayal shows a woman who is fragile, uncertain, and lost. She spends her days in bed, unable to summon the energy or will to move forward.

Takako’s transformation begins when she reluctantly accepts her uncle Satoru’s invitation to stay at the Morisaki Bookshop. Her character arc is one of slow yet steady personal growth, as she begins to find solace in the world of books and the quiet, musty charm of the bookshop.

Through reading, she begins to reconnect with herself, gradually rediscovering her identity and purpose. As she interacts with the bookshop’s customers and develops new relationships, she moves from a place of emotional paralysis to one of cautious hope and renewal.

Takako’s story is ultimately about healing and self-discovery. Her eventual openness to a new romantic relationship marks the conclusion of her emotional journey.

Satoru

Satoru, Takako’s uncle, is a pivotal character in her transformation and in the story’s emotional depth. He is a somewhat eccentric figure who runs the Morisaki Bookshop, which has been in the family for three generations.

Though his eccentricity is evident in his demeanor and the slightly chaotic atmosphere of the shop, Satoru is also marked by his own personal tragedy. His wife, Mako, abandoned him five years prior to the events of the novel. Despite this, he remains hopeful, albeit tinged with sadness.

Satoru’s offer to Takako to live in the bookshop is not only an act of kindness but also one of self-interest. He too is lonely and possibly hopes that her presence will bring some warmth back into his life.

His character is layered with a quiet resilience, and he shows immense patience and understanding toward Takako, even as she initially resists his attempts to help. Satoru’s bond with books reflects his inner world—a life of introspection and retreat from emotional vulnerability, at least until the return of Mako disrupts his carefully constructed peace.

Mako

Mako is introduced in the second half of the book as Satoru’s estranged wife, the woman who left him without explanation five years ago. Her return brings both conflict and resolution to the narrative.

Mako’s character is shrouded in mystery, and her abrupt departure from Satoru’s life is a source of lingering pain for both him and, indirectly, for Takako. When she reappears, she offers Takako the opportunity to embark on a journey—a physical and emotional one—up a mountain where they stay in a tea house and eventually begin to open up to one another.

Through this journey, Mako’s past begins to unravel, and her reasons for leaving Satoru become clearer. Her character serves as a catalyst for both Takako and Satoru’s emotional growth.

For Takako, Mako represents a figure of complexity and unresolved pain, but she also provides an example of facing the consequences of past actions. Mako’s eventual reconciliation with her own choices and the bond she forms with Takako in the process adds emotional depth to the story. It further emphasizes the theme of healing and self-discovery.

The Bookshop and Its Customers

While not personified in the traditional sense, the Morisaki Bookshop itself functions almost as a character within the novel. It is described as old, musty, and full of dusty secondhand books, symbolizing both the weight of history and the potential for new beginnings.

The bookshop serves as the backdrop for much of Takako’s transformation. It is a space where various colorful customers come and go, contributing to her re-engagement with the world.

These regulars provide Takako with a window into lives beyond her own, helping her re-establish a sense of community and belonging. The bookshop’s patrons, though not explored in significant depth individually, contribute to the overall charm of the story. Their presence reflects the subtle beauty of human interaction and the solace that can be found in shared spaces like bookstores.

Themes

The Interplay of Solitude and Rebirth Through Isolation

At its core, Days at the Morisaki Bookshop delves into the transformative power of solitude, as manifested in Takako’s withdrawal from society following the emotional collapse triggered by her lover’s betrayal. However, this solitude is not depicted as a descent into mere isolation or depression; rather, it is a fertile ground for rebirth.

Takako’s seclusion in the musty, claustrophobic confines of the Morisaki Bookshop symbolizes an internal journey of introspection, much like a cocoon where personal reconstruction can take place. The dusty books that surround her become metaphors for forgotten stories—perhaps her own neglected potential—waiting to be uncovered and revived.

The transition from passive, bed-bound inertia to tentative engagement with the world outside mirrors the slow but inevitable process of rebirth that solitude can engender. In a world where personal value is often tied to social productivity, the novel suggests that disengaging from the external can be a necessary step toward reclaiming a sense of self.

Emotional Paralysis and the Slow Process of Healing

One of the more profound thematic explorations in the novel is the way emotional trauma manifests as a form of physical and psychological paralysis. Takako’s initial reaction to her lover’s betrayal is to retreat into a state of near-catatonic immobility—quitting her job and spending days in bed.

This stagnation is representative of a common but often overlooked human response to emotional injury: the tendency to cease functioning altogether when overwhelmed by grief or betrayal. Healing, as portrayed in this narrative, is not a linear or swift process but one that mirrors the slow, deliberate, almost imperceptible shift from stillness to movement.

The physicality of her slow return to daily tasks at the bookstore, as well as the symbolic act of reading dusty, long-forgotten books, serves as a metaphor for the often painstaking process of emotional recovery. Rather than offering a quick fix, the novel respects the slow, layered nature of healing—a return to life through small, almost mundane acts of self-care and re-engagement with the world.

The Rediscovery of Identity Through Intellectual and Sensory Exploration

Takako’s journey in Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is not merely a recovery from emotional despair but also a rediscovery of identity. As she immerses herself in the world of books, the act of reading serves as a vehicle for intellectual and sensory exploration.

The books she consumes become more than just an escape from her present condition; they are mirrors, guiding her through the labyrinth of her own inner life. The novel suggests that identity, especially when fractured by emotional crises, can often be rebuilt through the act of engagement with art and literature.

The dusty, timeworn books are not just relics of the past but invitations to a deeper connection with human experience. Takako’s intellectual journey is paralleled by the sensory experience of the bookshop itself—the smell of old paper, the quiet shuffle of customers, and the serene isolation of the bookstore.

The Tension Between Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Japan

Though not overtly political or sociological, the novel offers subtle commentary on the tensions between tradition and modernity in contemporary Japanese society, symbolized by the Jimbocho district and the Morisaki Bookshop itself. The bookstore, an emblem of a bygone era, with its dusty volumes and slow, deliberate pace, stands in contrast to the fast-paced, emotionally detached world Takako leaves behind when she quits her job.

Her initial rejection of the bookshop’s old-world charm and her gradual acceptance of its offerings can be seen as a broader reflection of Japan’s own complex relationship with modernity. The novel subtly critiques a society that prioritizes corporate achievement and consumerism over personal fulfillment.

Tradition—represented by the aging bookstore, the familial bond with Uncle Satoru, and the old books—is where one might find not only personal salvation but also the answer to deeper societal malaise. The novel asserts that there is something sacred and transformative in the analog, in the handwritten note left in a book, or in the slow process of reading itself.

Familial Estrangement and the Search for Emotional Closure

A central emotional arc in the novel involves the theme of familial estrangement, as illustrated by both Takako’s distant relationship with her uncle and the more pronounced estrangement between Uncle Satoru and his wife, Mako. The arrival of Mako in the latter half of the novel forces a reckoning with unresolved family trauma, revealing the ways in which the past continues to haunt the present.

Takako’s initial reluctance to engage with her aunt mirrors her own reticence to confront her emotional wounds. The novel uses this strained family dynamic to explore how forgiveness, reconciliation, and emotional closure are not singular events but processes.

The journey that Takako and Mako undertake, both literal and metaphorical, symbolizes the slow and often painful excavation of buried emotional truths. As secrets are revealed and bonds are rebuilt, the novel emphasizes that familial ties, though fraught with complexities, remain one of the few pathways to true emotional closure.

The Bookstore as a Sanctuary: Spaces of Quiet Transformation

The physical space of the Morisaki Bookshop itself functions as more than just a setting; it is a thematic symbol of sanctuary and quiet transformation. Unlike the bustling, impersonal world outside, the bookstore provides a refuge, a place where time seems to slow down and personal reinvention becomes possible.

The novel suggests that such spaces—whether they are physical like the bookshop or metaphorical like the inner world of literature—are necessary for human flourishing. The bookstore’s atmosphere of gentle neglect, with its dusty corners and aging bookshelves, reflects a kind of neglected inner life that, once tended to, can become fertile ground for personal renewal.

Takako’s transformation is intimately tied to the bookstore itself, illustrating how certain spaces can facilitate profound internal shifts by providing the quiet, contemplative environment needed for introspection and growth.