Dead of Summer Summary, Characters and Themes

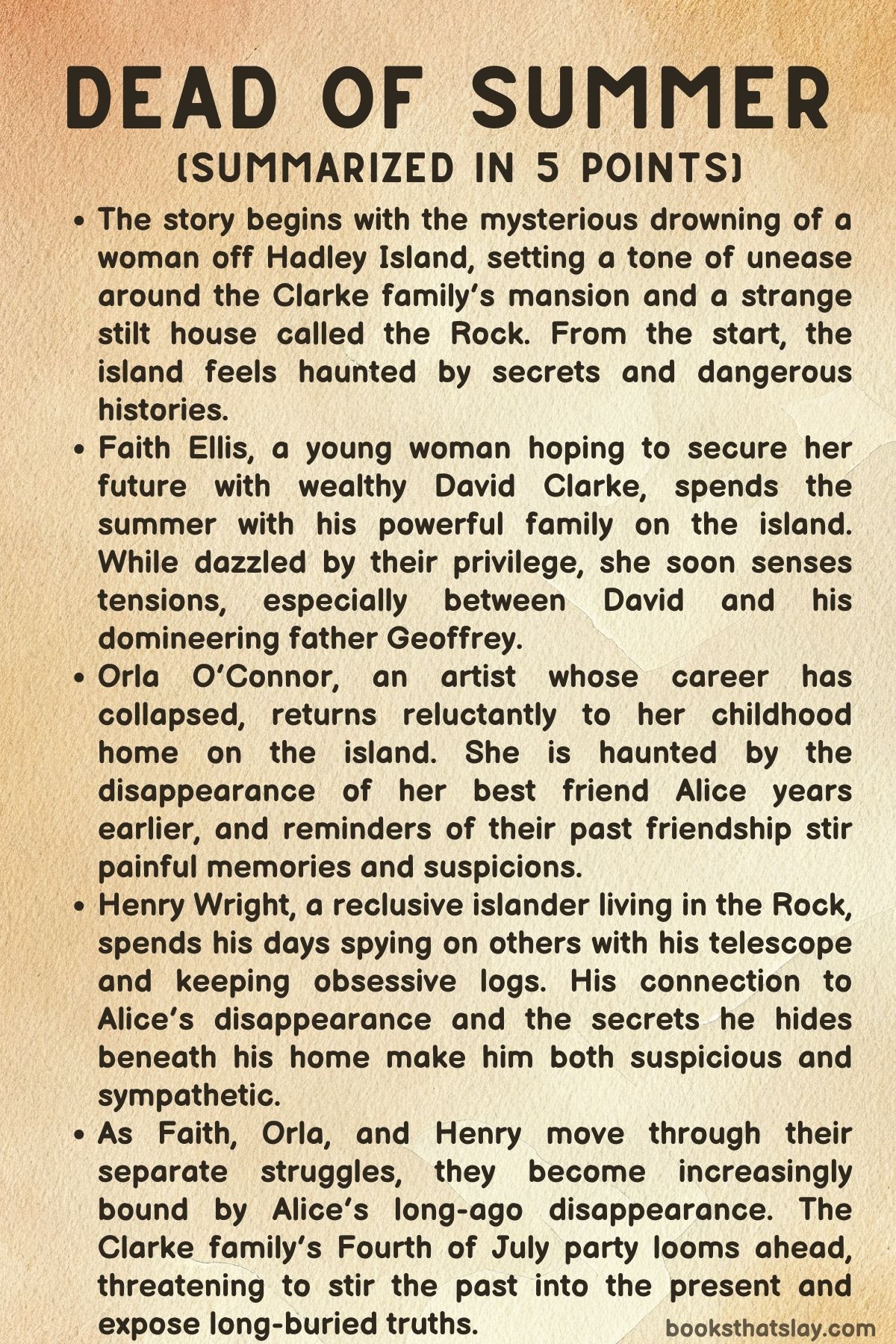

Dead of Summer by Jessa Maxwell is a suspenseful and atmospheric thriller set against the eerie backdrop of Hadley Island. The novel explores the weight of secrets, class divides, and the consequences of silence through the perspectives of three central characters—Faith Ellis, Orla O’Connor, and Henry Wright.

Each is bound in different ways to the unsolved disappearance of Alice Gallo, a teenage girl who vanished years ago during a summer of privilege, betrayal, and power. As new events on the island echo the past, hidden truths resurface, unraveling the carefully constructed lives of the Clarke family and those entangled with them.

Summary

The novel begins with the chilling image of a woman drowning near Hadley Island. Her desperate struggle against the dark waves sets the tone for a story that circles back to a past tragedy: the mysterious disappearance of Alice Gallo years earlier.

Faith Ellis enters the Clarke family’s privileged world through her relationship with David Clarke. Coming from modest roots, she is eager to belong, though she constantly feels out of place.

Early in the summer, she discovers an engagement ring in David’s suitcase, fueling her hope for security and acceptance. But life inside the Clarke mansion unsettles her.

Geoffrey Clarke, David’s ruthless father, dominates the household, pulling David into his business dealings and controlling their every move. Faith becomes both dazzled by the glamour and unnerved by the secrecy, especially after learning about the island’s history with Alice Gallo.

Meanwhile, Orla O’Connor reluctantly returns to Hadley Island after years away. Once a promising artist, her career collapsed after she passed off Alice’s artwork as her own.

She remains haunted by the loss of Alice, her best friend, and the betrayal that fractured their dreams. Settling back into her childhood home, Orla is tormented by memories, visions, and the decaying Gallo house next door.

The island seems alive with echoes of the past, and she cannot shake the sense that Alice still lingers there.

Out at sea, Henry Wright lives in the Rock, a stilted house with his wife Margie. Once accused of Alice’s disappearance, he has lived in exile, condemned by the islanders’ suspicions.

Henry spends his days obsessively watching the island through a telescope, recording people’s activities in detailed logs. He notices the return of the Clarke family, Orla’s reappearance, and strange movements in Alice’s abandoned house.

His observations, though obsessive, reveal glimpses of truths others wish to bury.

As the summer unfolds, tensions heighten. Faith grows increasingly isolated in the Clarke mansion.

Her attempts to settle into the family’s opulent lifestyle are shadowed by overheard arguments between David and Geoffrey, references to “the girl,” and whispered accusations about Henry Wright. Faith’s unease deepens when she breaks into Geoffrey’s office and discovers disturbing documents: photographs, nondisclosure agreements, and hints of women silenced by the family’s influence.

Her vision of marriage to David begins to fracture under these revelations.

Orla confronts her own guilt and fractured identity. When David visits her drunkenly one night, he cruelly reminds her of her fraudulent use of Alice’s artwork.

Their conversation dredges up old attractions, lingering guilt, and veiled threats. Orla’s growing paranoia pushes her closer to unraveling, especially when she finds Alice’s old mural defaced with sinister alterations.

Encounters with locals, like the fisherman Walter, further fuel her suspicions that the Clarke family has always been at the center of the island’s darkest stories.

Henry’s world begins to collapse as well. His wife dies, leaving him alone with his obsessions.

Locals accuse him again after Gemma, a young waitress, disappears. Jean, his sister-in-law, discovers his logbooks and berates him for spying.

Henry insists he saw Gemma alive with a man, but his reputation as a suspect resurfaces, echoing his wrongful implication in Alice’s disappearance years earlier.

The Clarke family’s long-abandoned Fourth of July party becomes the climax of the story. Geoffrey revives the event as a display of wealth and control, announcing his retirement and David’s succession.

During the party, Faith is proposed to publicly, though the moment feels like a performance more than a declaration of love. On Geoffrey’s yacht, she discovers Gemma held captive and narrowly escapes with her help, nearly drowning before Henry rescues them—proving himself the opposite of the monster the island believed him to be.

At the same time, Orla and David confront their past. Orla recalls the fateful night when she and David witnessed Alice drugged and exploited on the Clarke yacht.

In a fit of fear and desperation, David had shoved Alice overboard, and Geoffrey orchestrated a cover-up, shifting suspicion onto Henry. Orla, silenced by fear and shame, had remained complicit.

Alice, however, had not died. Rescued and forced into silence by Geoffrey’s power, she disappeared from the island, carrying the weight of trauma for years.

Alice’s return shocks both Orla and David. In the decaying Gallo house, she reveals the full truth—David’s guilt, Geoffrey’s cover-up, and Orla’s betrayal.

Faith arrives, aligning herself with Alice after discovering her own connections to Geoffrey’s manipulations. A confrontation ensues, culminating in the collapse of the rotting house.

David falls to his death, while Orla survives, crushed under the weight of his body but alive.

In the aftermath, the web of silence and power begins to unravel. Geoffrey’s empire crumbles as Gemma bravely testifies and Alice reclaims her voice.

Faith severs herself from David’s shadow, finding strength in her bond with Alice. Orla, though scarred by guilt, begins the path toward recovery.

Henry, once vilified, is finally vindicated and integrated back into the community.

The novel closes with reflection. Henry contemplates survival and the futility of hiding from life’s cruelties.

Orla faces her complicity while seeking renewal in her art. Alice, once silenced, reclaims her agency and place in the world.

Faith emerges with independence, freed from the Clarke family’s toxic grasp. Together, their lives stand as a testament to the enduring scars of secrets—and the liberating power of truth brought to light.

Characters

Faith Ellis

Faith Ellis is portrayed as a woman caught between the worlds of modest origins and the alluring promise of wealth and acceptance. Her discovery of the Cartier engagement ring at the start of the novel immediately defines her desire for stability, status, and belonging, while also exposing her insecurity about her place within David Clarke’s powerful family.

Throughout Dead of Summer, Faith embodies the tension between outward perfection and inner fragility. Her polished appearance and careful social performances mask deep anxieties about her past and a recurring fear of exposure.

Her journey shifts from one of passive anticipation—waiting for David’s proposal and acceptance—into active defiance, as she uncovers secrets hidden by Geoffrey Clarke and confronts the dark truths surrounding David. In the end, Faith evolves from a woman defined by others into one who asserts control, aligning herself with Alice and rejecting the cycle of silence and complicity that sustains the Clarke family’s power.

David Clarke

David Clarke is introduced as Faith’s charming and privileged boyfriend, but beneath the surface, he embodies weakness, entitlement, and the toxic inheritance of his father’s influence. His unease around Geoffrey hints at a history of control and manipulation, yet David himself perpetuates similar patterns, particularly in his treatment of women.

His teenage relationship with Orla and his role in Alice’s disappearance reveal his selfishness and cowardice, as he places his own preservation above truth or justice. Even as an adult, David oscillates between seductive charm and sinister secrecy, drawing Faith close while keeping her excluded from the truth.

His downfall occurs when his lies and violence can no longer be hidden, and his attempt to protect himself ends with his death—a symbolic collapse of the Clarke dynasty’s corrupt legacy.

Geoffrey Clarke

Geoffrey Clarke stands as the embodiment of patriarchal authority, wealth, and unchecked power in Dead of Summer. Cold, domineering, and manipulative, he exerts complete control over both his family and his associates, dictating their choices under the guise of legacy and tradition.

His revival of the Fourth of July party, long associated with Alice’s disappearance, illustrates his arrogance and his disregard for the scars left by past tragedies. Geoffrey’s moral corruption is revealed through his complicity in Alice’s silencing and his efforts to conceal David’s crime, which intertwine exploitation with financial and social domination.

His intimidation of Faith—using her past to ensure obedience—exemplifies his predatory need for control. Yet, when Gemma and Alice finally expose the truth, Geoffrey’s empire collapses, leaving him powerless, stripped of the silence that once protected him.

Orla O’Connor

Orla O’Connor is a character marked by guilt, grief, and the collapse of youthful dreams. Once an ambitious artist, her life is defined by the disappearance of Alice, her closest friend, and by her decision to appropriate Alice’s artwork to build her own career.

Her return to Hadley Island forces her to confront both the literal ghosts of her past and the metaphorical ones—her compromised integrity, her shame, and her unresolved feelings for David. Orla’s perception of herself is fractured, torn between longing for validation and fearing exposure as a fraud.

Her eventual confrontation with Alice and the truth about that fateful night is both devastating and redemptive, as she must face her complicity in maintaining silence. Though her survival after David’s death is physically brutal, it marks the beginning of an inner recovery, allowing her to start moving forward from years of stasis and regret.

Henry Wright

Henry Wright serves as both a scapegoat and an unlikely savior within the novel. Branded a pariah after being falsely implicated in Alice’s disappearance, he lives in isolation with his telescope and logbooks, obsessively watching others as a means of control over his otherwise powerless existence.

His voyeurism positions him as morally ambiguous, yet his humanity and vulnerability emerge through his care for his ailing wife, Margie, and his ultimate act of saving Faith and Gemma. Henry symbolizes the destructive power of rumor and prejudice, as his life was ruined not by his own crime but by the community’s eagerness to cast blame.

By the novel’s end, Henry is vindicated and reconnected to the community, his quiet redemption underscoring the theme of truth’s eventual triumph over lies.

Alice Gallo

Alice Gallo is the haunting figure at the heart of Dead of Summer, both literally and symbolically. Presumed drowned as a teenager, she is instead revealed to have survived, her life irrevocably altered by trauma, coercion, and enforced silence.

As a girl, she was ambitious and restless, dreaming of escaping the island with Orla to pursue art, but also pragmatic and willing to seek shortcuts to independence. Her disappearance becomes the central mystery shaping all the characters’ lives, binding them together in lies and guilt.

When she reemerges, Alice is no longer a ghostly memory but a survivor determined to reclaim her voice. Her confrontation with David, Orla, and Geoffrey not only exposes the truth but also restores her agency.

In the end, Alice transforms from victim to witness, helping dismantle the Clarke family’s power and building a bond with Faith that signifies solidarity, healing, and resilience.

Gemma

Gemma, though a more minor character, plays an important role as a mirror of Alice’s younger self and as a catalyst for the final unraveling of the Clarke family’s secrets. A young waitress with dreams of leaving for Paris, Gemma represents innocence, hope, and the vulnerability of youth within a predatory world.

Her disappearance echoes Alice’s, drawing the island back into the cycle of suspicion and fear, and her captivity on Geoffrey’s yacht exposes the continued exploitation of girls by powerful men. Gemma’s courage in speaking publicly about what happened shatters the silence Geoffrey depended on, helping shift the narrative away from blame placed on outsiders like Henry and toward the true perpetrators.

Themes

Power, Wealth, and Corruption

In Dead of Summer, power is inseparable from wealth, and wealth is inseparable from corruption. The Clarke family represents the pinnacle of privilege on Hadley Island, their sprawling mansion and control over social events reinforcing their dominance.

Geoffrey Clarke, in particular, uses his fortune as both shield and weapon, dictating the lives of those around him and silencing inconvenient truths through influence and money. This theme underscores how wealth does not merely provide comfort, but actively manipulates justice and morality.

The false accusations against Henry, the concealment of Alice’s disappearance, and the silencing of women through non-disclosure agreements demonstrate the way money is wielded to distort reality. What makes the theme powerful is how the characters are forced to measure themselves against this system—Faith, entering from a modest background, must learn to navigate the Clarke’s world of appearances, while Orla is reminded of her youthful compromises tied to ambition and survival.

The book demonstrates that corruption is not an isolated act but a culture that perpetuates itself through intimidation, secrecy, and transactional relationships. By the end, Geoffrey’s empire begins to fracture not because of a moral awakening among the powerful, but because of those previously silenced reclaiming their agency.

Wealth here is not portrayed as a mere backdrop but as an engine of abuse, shaping every decision, every silence, and every betrayal that defines the story.

Guilt and Complicity

The novel explores how guilt shapes identity and action over the years, and how complicity in silence becomes as damaging as direct wrongdoing. Orla’s life is overshadowed by the disappearance of Alice, not only because she lost her closest friend but because she failed to tell the truth when it mattered most.

Her artistic fraud, built upon Alice’s work, becomes a manifestation of her deeper moral failure, making her professional collapse inseparable from her personal shame. Faith too is caught in a similar web—her willingness to overlook David’s evasiveness and Geoffrey’s intimidation is fueled by her desire for belonging, and her silence in critical moments mirrors Orla’s earlier choices.

Even Henry, though less guilty than others, embodies complicity through passivity: his obsessive watching and failure to intervene make him a man burdened by what he did not do. This theme forces the reader to consider how silence becomes an active form of betrayal.

The guilt of omission corrodes the characters, leaving them stuck in cycles of fear, secrecy, and self-destruction. Ultimately, the unraveling of the truth illustrates that guilt cannot be permanently buried, and complicity exacts a cost far greater than immediate confrontation ever would.

The novel insists that truth withheld is itself a lie, and the weight of it presses down on every character until their choices are exposed.

Trauma and Memory

The narrative demonstrates how trauma refuses to fade, instead embedding itself into the fabric of daily life and reshaping memory into something unstable and haunting. Orla’s return to the island triggers a flood of memories that blend with paranoia and drug-induced haze, making her uncertain of what is real and what is imagined.

Her fractured recollections of Alice are more than just nostalgia; they are evidence of how trauma distorts, erasing clarity and leaving space for guilt and fear to rewrite the past. Henry too lives within memory, trapped by his logbooks and his obsessive watching, attempting to order chaos through surveillance, but in reality imprisoned by the trauma of false accusations and public humiliation.

Faith’s nightmares of exposure reflect her own fears of being discovered, linking personal insecurities with the generational trauma imposed by the Clarke family’s manipulations. The resurfacing of Alice not as a ghostly absence but as a living person emphasizes how trauma does not vanish even when the victim survives—it lingers in secrecy, silencing, and the inability to fully reclaim one’s voice.

Memory throughout the book acts less as an accurate record and more as a battlefield, a place where truth, lies, and repression struggle for dominance. This theme underlines that healing requires not just remembering, but reinterpreting memory without fear.

Identity, Belonging, and Reinvention

Questions of who belongs and who can reinvent themselves are central to Dead of Summer. Faith is the clearest example, a woman who tries to shed her modest background by reshaping herself into someone worthy of the Clarke family’s approval.

Yet her performance of identity constantly collides with her insecurities, reminding her that reinvention is fragile when rooted in deception and external validation. Orla embodies another form of reinvention—an artist who rebuilt her life using Alice’s work, attempting to claim greatness through borrowed identity, only to collapse under the weight of fraud and failure.

Even Alice’s own trajectory is shaped by forced reinvention; her silence and disappearance are a coerced transformation into someone who must live under an assumed narrative to protect herself. Henry too is bound by identity, his reputation as an outcast sealing him into the role of suspect long after the truth is buried.

Belonging, whether to family, community, or art, becomes elusive, often tied to lies or compromises. Yet by the conclusion, reinvention takes on a different form: not as a mask but as liberation.

Faith finds belonging not in the Clarke family but in her friendship with Alice. Henry finds a quieter role in community rather than isolation.

Orla begins to accept her failures while seeking authenticity. The novel presents identity not as something one fabricates for survival, but something reclaimed when the false narratives of others are stripped away.

Justice and Truth

The search for truth runs parallel with the pursuit of justice, and the novel highlights how rarely they align in a world dominated by influence and silence. Alice’s disappearance is obscured by a constructed narrative, with Henry cast as the scapegoat and Geoffrey using his wealth to control the legal and social consequences.

For years, the truth is buried not because it is unknowable, but because it is inconvenient to those in power. Orla’s lies, Faith’s silences, and David’s guilt illustrate how truth becomes fragmented when filtered through fear and selfishness.

The story suggests that justice is not found in institutions, which fail repeatedly, but in acts of personal courage. Gemma’s decision to speak out, Alice’s return and testimony, and Faith’s rejection of Geoffrey’s manipulation all embody a reclamation of truth that begins to undo decades of corruption.

Yet justice here is not triumphant; it is messy, partial, and often arrives too late to save everyone. David’s death, Orla’s career collapse, and Alice’s lost years are irreversible losses.

Still, by unearthing the truth, the survivors carve out space for new beginnings, however scarred. The novel emphasizes that justice cannot undo the past but can dismantle the falsehoods that sustain ongoing harm.

Truth, long suppressed, becomes the only form of resistance against the structures of wealth and silence that dominate Hadley Island.