Deadbeat by Adam Hamdy Summary, Characters and Themes

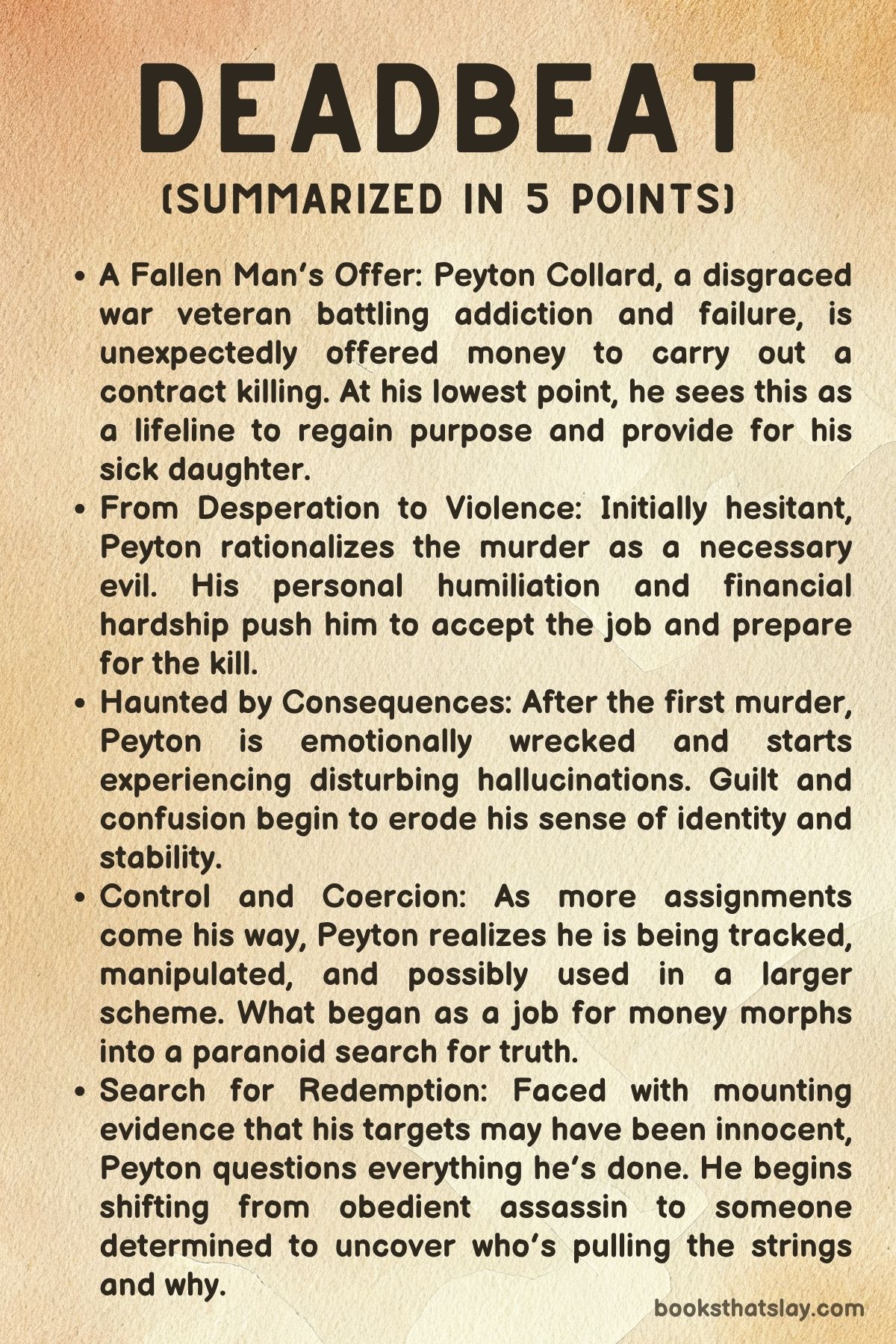

Deadbeat by Adam Hamdy is a raw, unflinching psychological thriller that examines the wreckage left behind by addiction, desperation, and moral compromise. At its core, the novel is a character study of Peyton Collard, a man broken by past mistakes, entangled in a cycle of self-destruction, and manipulated into violence under the illusion of redemption.

Hamdy builds a bleak yet propulsive narrative that explores the limits of personal responsibility and the seductive nature of vigilante justice. Through Peyton’s descent and eventual awakening, the novel scrutinizes the societal systems that fail the vulnerable and interrogates whether one can ever truly be redeemed after crossing irrevocable lines.

Summary

Peyton Collard’s life is already in shambles when the story begins. He wakes in his decrepit home in Long Beach, strung out from a combination of alcohol and ketamine.

His car is being repossessed, and in a drunken panic, he crashes into a sheriff’s vehicle. Arrested and facing multiple charges—including a parole violation linked to a prior vehicular manslaughter conviction—Peyton is at the brink of a ten-year prison sentence.

His only lifeline is Mitch Hoffman, a hopelessly outmatched public defender who advises a plea deal. Peyton is overwhelmed by guilt and regret, particularly over how his daughter, Skye, will suffer in his absence.

Unexpectedly, Peyton is released on a $100,000 bail paid by an anonymous benefactor. He receives a package containing a grand in cash and a link to a website that offers him $100,000 to kill a man named Walter Glaze, described as a criminal with a history of drug dealing and violence.

Strapped for money and haunted by Skye’s deteriorating health and stalled dreams, Peyton is tempted. His research confirms Glaze’s shady associations, but Peyton remains morally torn.

Seeking validation, he confides in Jim, a veteran who casually endorses killing criminals. Peyton also attempts to reconnect with Skye and his ex-wife Toni, but finds himself met with disappointment and alienation.

His resolve hardened by rejection and the dream of providing for Skye, Peyton begins tracking Glaze. A visit to Ultima, Glaze’s nightclub, leads him to a surreal encounter with Attica Douglas, an alluring woman who introduces him to new drugs and temporarily revives his sense of worth.

When Glaze appears at the club, Peyton lashes out and is quickly thrown out. Humiliated and drunk, Peyton decides to acquire a firearm from a pawn shop contact, inching closer to fulfilling the contract.

He returns to his ex’s home for a final visit and meets Jack, Toni’s new partner—a painful reminder of all he’s lost. Later, he meticulously plans the hit: wearing black, writing a farewell letter to Skye, and arming himself.

But the murder does not go as intended. Glaze discovers Peyton before he can act.

In the ensuing chaos, Peyton botches the attack and gets beaten. Fueled by rage, he stalks Glaze again, kidnaps him at gunpoint, and after a struggle, kills him in a panic.

He attempts to stage a robbery to cover up the murder, but guilt consumes him. Though a package of $100,000 arrives, confirming his success, Peyton is haunted by the psychological aftermath.

His visions of Glaze’s death and ghost hint at deepening trauma and remorse. Another hit offer arrives, this time for a woman named Farah Younis.

Peyton accepts the job and receives $200,000. Still under suspicion by LAPD detective Rosa Abalos and threatened by gangsters, Peyton buries the murder weapon and tries to start a new life.

He rents a house in Laurel Canyon and stashes some money.

Despite attempts at normalcy, Peyton’s violence spirals further. A brawl involving Jim and gangsters Cutter and Curse ends with Peyton in possession of yet another weapon.

He tries to prove to Toni and Skye that he’s changing, even hiring a high-profile lawyer, Anna Cacciola. But the third assignment—murdering Father Richard Gibson, a retired priest accused of abuse—pushes him to the edge.

He goes through with it, shooting Gibson after a confrontation. Yet, something about the peaceful surroundings and Gibson’s final words disturbs Peyton deeply.

Later, Peyton searches the internet and finds that online evidence framing his victims as villains has disappeared. In their place are stories showing them as decent, generous people.

He realizes with horror that he has been used to murder innocent individuals. This unraveling truth sends Peyton into a psychological spiral.

He resumes drinking and taking drugs, culminating in an embarrassing outburst outside Toni’s home, witnessed by Skye.

He receives his next assignment: killing Alice Polmar. Peyton follows her and plans the hit, but in a moment of clarity, he fakes her death instead, staging the scene to protect her.

When he returns home, Rosa arrests him, but the discovery that Alice is alive challenges the legal assumptions of his guilt. He escapes police custody and hides with Felicity, a woman carrying her own history of violence and trauma.

Their shared pain builds a tentative connection, and she helps him investigate the real architect behind the murders.

Their search reveals that all of Peyton’s targets had received organ transplants from Freya Persico—the young woman Peyton killed in his past accident. The trail leads to her father, Joseph Persico, a powerful man dying of cancer who orchestrated the murders to recover organs containing his daughter’s genetically engineered cells.

Persico manipulated Peyton’s desperation, engineering the hits under the guise of justice.

Peyton confronts Persico, who reveals a final threat: he had plans to harm Skye. A violent confrontation ends with Persico’s death—killed by his own high-tech security system.

Peyton frees a drugged Rosa, erases security footage, and escapes. Though later arrested, Peyton is eventually released due to legal maneuvering by Anna and evidence implicating Persico and his criminal associate, Frankie Balls.

Now a free man, Peyton retrieves his hidden cash and begins rebuilding his life. He lives quietly with Felicity in Topanga, working with his hands and remaining sober.

His relationship with Skye and Toni is strained but not beyond repair. Though he has committed unforgivable acts, Peyton tries to live honorably going forward.

In the final reflections, Peyton acknowledges his sins but refuses to shy away from them. He recognizes the systemic failures that led to his downfall and challenges readers to confront their own complicity in the systems that perpetuate suffering.

By the end, Peyton’s story is framed as fiction, though its emotional truths and moral questions leave a lasting impact.

Characters

Peyton Collard

Peyton Collard is the fractured soul at the heart of Deadbeat, a man whose journey is marked by desperation, addiction, and a fragile yearning for redemption. Once a father and perhaps once a dreamer, Peyton’s life has disintegrated into a haze of ketamine, alcohol, and guilt.

His opening scenes portray him at rock bottom—inebriated, broke, and being hauled away by the police after crashing into a sheriff’s car. This physical and psychological crash is emblematic of the deeper spiral he has long been engaged in.

Peyton’s criminal past, especially the vehicular manslaughter that took an innocent life, is not just a stain on his record but a wound he cannot stop reopening.

What defines Peyton most compellingly is the tension between his guilt and his love for his daughter, Skye. She becomes his North Star in a nightmarish moral fog.

When he receives the offer to kill Walter Glaze for money, the temptation is not driven purely by greed, but by a fractured paternal instinct—a belief that the blood money might cure his daughter’s possible illness and rescue her dreams. As the story progresses, Peyton morphs from a reluctant assassin to someone convinced, at least temporarily, that he’s delivering justice.

But each act of violence chips away at his psyche. He hallucinates his victims, drowns in guilt, and eventually realizes the manipulation he’s suffered.

By the end of his arc, Peyton is no longer merely a man reacting to trauma but someone actively reckoning with his role in a systemic horror. He may find a semblance of peace in Topanga, but the question of whether he’s truly redeemed lingers.

Skye Collard

Skye Collard is the emotional anchor and moral mirror of Deadbeat. Thirteen years old and remarkably mature for her age, Skye represents the purity and potential that Peyton fears he has irreparably damaged.

Her presence in the narrative is subtle yet immensely powerful—every action Peyton takes, no matter how misguided, is in some way tied to his desire to do right by her. Skye’s dreams of becoming a doctor juxtapose painfully with the world her father drags her through—a world of broken promises, drug-fueled outbursts, and criminal repercussions.

She doesn’t have much dialogue, but her emotional presence speaks volumes.

Skye’s gradual disillusionment with her father is heartbreaking. Where she once saw him as a hero, she now sees a ghost of a man, stumbling through bad decisions.

The moment she witnesses Peyton outside her house in a drunken breakdown is pivotal—it crystallizes her understanding that her father might never become the man she hopes he can be. And yet, her existence remains Peyton’s only tether to reality, the last shred of goodness he clings to.

Her capacity for disappointment is matched only by the hope she somehow still inspires.

Toni

Toni, Peyton’s ex-wife, is a figure of exasperated strength and emotional fatigue. She has borne the weight of Peyton’s collapse, raising their daughter almost entirely on her own while managing the emotional scars left behind by his negligence.

Her attitude toward Peyton is sharp and justifiably bitter—she does not coddle his excuses or feed into his self-pity. Instead, she forces him to face the consequences of his absence and betrayal.

Toni becomes not just a voice of reason in the story, but also a symbol of reality—a stark contrast to Peyton’s delusions and justifications.

Her interactions with Peyton are laced with frustration, but there is an underlying grief as well—a mourning of what could have been if Peyton hadn’t fallen so far. When she introduces Jack, her new partner, it’s more than a romantic detail; it’s a signal to Peyton that life has moved on without him.

Despite everything, Toni does not villainize him entirely. She allows him small chances to connect with Skye, indicating that while trust is broken, it is not beyond repair.

Toni is a moral compass in the narrative, a reminder that actions have rippling consequences.

Jim

Jim, Peyton’s only real friend, serves as both a lifeline and an accelerant to his downward spiral. A former Marine hardened by violence, Jim lives in a world where morality is subordinate to survival.

He operates as Peyton’s access point to the tools of violence—supplying him with a gun, offering practical advice, and occasionally dragging him out of life-threatening trouble. Jim embodies a rugged, almost nihilistic sense of camaraderie.

His belief that “killing bad guys is just life” reflects a deeply fatalistic worldview that seeps into Peyton’s own justifications.

Yet Jim is more than just a criminal enabler. He’s a reflection of what Peyton might become if he fully gives in to moral surrender.

Their friendship is one forged in trauma, and Jim’s descent mirrors Peyton’s. In key scenes, such as the shootout with Cutter and Curse, Jim proves loyal, but his loyalty is a double-edged sword—it enables destruction even as it protects.

He does not judge Peyton, but neither does he guide him toward redemption. He’s the friend who won’t abandon you, even if it means holding the door open to hell.

Walter Glaze

Walter Glaze is introduced as a target—a supposedly nefarious drug dealer and nightclub owner—but evolves into a symbol of Peyton’s moral confusion. At first glance, Walter is arrogant and dismissive, especially in his brief interaction with Peyton at the Ultima nightclub.

But as Peyton investigates further and eventually confronts him, Walter reveals complexity. He pleads for his life, offers help, and reacts with humanity in his final moments.

This complicates Peyton’s understanding of justice. Walter is not the cartoon villain Peyton imagines but a man with ties, history, and nuance.

His murder marks a crucial turning point in the narrative. It is the first irreversible crossing of a moral boundary for Peyton.

The guilt that follows is not just about the act, but about the realization that Walter may not have deserved to die. Later revelations that paint Walter in a more generous light retroactively condemn Peyton’s actions further, showing that he has become a pawn in someone else’s vendetta.

Rosa Abalos

Detective Rosa Abalos serves as both antagonist and unlikely savior. Sharp, methodical, and driven, Rosa represents law and order in a world where rules have become elastic.

She suspects Peyton but lacks the evidence to bring him down fully. Her dogged pursuit puts pressure on him at critical moments, and yet she also inadvertently protects him—such as when her presence scares off Cutter and Curse.

Rosa is not portrayed as a villain; rather, she is one of the few characters still clinging to institutional justice in a landscape overrun by vigilantism.

In the final act, Rosa becomes a victim of the same manipulation that ensnared Peyton. Her drugging and imprisonment by Joseph Persico underscore how vulnerable even the righteous are in a world dominated by money and obsession.

Her survival, and eventual release by Peyton, suggests that while systems are flawed, individual justice may still have a role to play.

Felicity

Felicity is a late but vital addition to the narrative, offering Peyton a glimpse of what healing might look like. A woman haunted by her own past act of violence, Felicity provides understanding without judgment.

She and Peyton connect not through romance alone, but through a shared language of pain and regret. Her presence softens the tone of the final chapters, offering a counterweight to the story’s grim descent.

Through Felicity, Peyton begins to believe in transformation—not as erasure of guilt, but as a path toward responsibility and change. She is not his salvation, but a companion on the road toward it.

Joseph Persico

Joseph Persico is the story’s final, chilling antagonist. Wealthy, dying, and entirely unrepentant, Persico embodies a warped quest for immortality.

Manipulating Peyton to retrieve the organs transplanted from his deceased daughter, Persico’s motivations are grotesquely personal. His actions reveal a deeper rot—how power and privilege can co-opt even the most intimate tragedies.

Persico is not only responsible for multiple deaths but also tries to harm Skye, making him the most reprehensible figure in the narrative. His death, ironically caused by his own security measures, is a fitting end to a man undone by his obsession.

He forces readers—and Peyton—to confront how easily grief can be weaponized into destruction.

Themes

Addiction and Self-Destruction

Peyton Collard’s life is entrenched in a vicious cycle of substance abuse and emotional self-destruction. From the opening scene, where he awakens in a haze of alcohol and ketamine, the narrative makes it clear that his dependency is not only physical but psychological.

Addiction operates as both a symptom and a coping mechanism for deeper wounds—guilt over past decisions, particularly the death caused by his earlier vehicular manslaughter, and an overwhelming sense of failure as a father. These substances offer him a fleeting escape from the shame and despair that consume him, but they also magnify his vulnerabilities, leading him to choices that further sabotage his life.

His drug use repeatedly clouds his judgment—whether when stumbling into the Ultima nightclub, accepting dangerous substances from strangers, or descending into fits of paranoia and rage that drive his actions.

The narrative doesn’t romanticize addiction but instead presents it in stark, unflinching realism. The physical and emotional degradation is mirrored in the decaying world around him—abandoned cars, pawn shops, grimy city buses, and cheap whiskey bottles.

Even when given moments of reprieve, like interacting with Skye or meeting Felicity, Peyton struggles to maintain sobriety, indicating how deeply addiction is rooted in his identity. His periodic lapses are never treated as isolated incidents but as part of a broader pathology, revealing how difficult it is to escape addiction without genuine transformation.

In this regard, Deadbeat critiques societal neglect of mental health and rehabilitation, portraying addiction as not just a personal failure but a reflection of systemic failure as well.

Fatherhood and the Burden of Redemption

Peyton’s motivations are shaped almost entirely by his relationship with his daughter Skye. Her existence is the fragile tether that keeps him anchored to any semblance of hope or morality.

Despite his repeated failures, Peyton’s vision of redemption revolves around her—his desire to provide, to protect, and ultimately to be seen through her eyes as someone worthy of love and respect. The tragedy is that his interpretation of fatherhood becomes warped by desperation.

He begins to equate redemption with financial provision and vengeance masked as justice, convincing himself that killing criminals is an act of love. The narrative shows how his fatherhood becomes a double-edged sword: a redemptive motivator and a source of crushing guilt.

Skye’s disillusionment with Peyton is heartbreaking but necessary. She evolves from admiration to pity, from excitement at his rare appearances to silent judgment.

This transition forces Peyton to confront the uncomfortable reality that emotional presence matters more than heroic sacrifices or grand gestures. His efforts to stage murder as moral necessity crumble under the weight of Skye’s silent disappointment and Toni’s cold clarity.

Even in the final chapters, when Peyton seeks a quiet life, his reconnection with Skye is tinged with the recognition that some wounds might never fully heal. Deadbeat explores how fatherhood is not about one grand act of redemption, but about consistency, honesty, and a willingness to confront one’s own darkness for the sake of another.

Peyton’s journey becomes a meditation on how easy it is to mistake control for care and how redemption, when rooted in ego, can lead to further ruin.

Moral Ambiguity and the Illusion of Justice

At the heart of Peyton’s transformation into a killer lies a carefully constructed illusion—that his victims are monsters, that his actions serve justice, and that he is acting out of moral necessity. This theme is unravelled methodically as he discovers that Walter Glaze, Farah Younis, and Father Richard Gibson were not the villains he was led to believe they were.

The anonymous AI-generated assignments and fake websites are a cruel distortion of truth, allowing someone like Joseph Persico to manipulate others into committing atrocities under the guise of righteousness. Peyton becomes a puppet in a system that weaponizes moral grayness for personal gain, showing how easily notions of justice can be corrupted when filtered through desperation and misinformation.

Peyton’s attempts to rationalize his actions fail when confronted with the humanity of his victims. Father Gibson’s art and final plea, Farah’s community service, and Glaze’s calm attempts at de-escalation all challenge Peyton’s self-constructed narrative.

This leads to a devastating realization: he is not a vigilante, but an executioner manipulated by a system of lies. The theme is especially resonant in a time when online misinformation and algorithmic manipulation affect real-world violence and perceptions of justice.

Peyton’s crisis becomes a reflection of how easy it is to believe one is on the right side, especially when that belief serves to mask guilt and fear. Deadbeat does not offer easy answers but forces readers to confront the discomforting idea that moral clarity is often a luxury unavailable to those in crisis, and that justice can be used as a smokescreen for revenge.

Capitalism, Desperation, and the Commodification of Violence

The commodification of violence emerges as a disturbing undercurrent throughout Deadbeat. Peyton is not offered help, rehabilitation, or support—instead, he is presented with a cash incentive to kill, the very embodiment of capitalist exploitation.

His desperation is monetized; his emotional instability, economic ruin, and paternal guilt are turned into levers for profit and power by Persico. The structure that traps Peyton is not just criminal but economic.

He is offered cash for murder, dangles between homelessness and a cottage in the hills, and must choose between his soul and his daughter’s diabetic care. These choices reflect a brutal hierarchy where survival depends not on morality, but on one’s willingness to participate in systemic cruelty.

The AI-generated messages and impersonal envelopes of cash represent a dehumanized economy where human life is assigned a price tag. Even justice is outsourced to private interests who hide behind digital layers.

As Peyton sinks deeper into this system, his decisions stop being truly his own; instead, he becomes a disposable cog in a larger machine driven by money and revenge. The system doesn’t care whether he lives, dies, or falls apart—only that he completes the task.

In this way, Deadbeat critiques a society that treats the poor and desperate as both perpetrators and victims of violence, reinforcing cycles of exploitation under the guise of justice and opportunity.

Identity, Guilt, and the Possibility of Transformation

Peyton’s arc is marked by a shifting sense of self that constantly clashes with his past and present actions. His efforts to reinvent himself—whether by impressing Attica at the nightclub, building a home in Laurel Canyon, or presenting as a doting father—are rooted in the hope that identity is fluid, that he can outrun his past through good intentions or new surroundings.

But these attempts collapse under the weight of guilt, which stalks him in the form of literal and figurative ghosts. His identity is haunted, fractured by the knowledge that he has become what he once feared: a killer, an absentee father, a pawn in someone else’s game.

Guilt becomes the force that both paralyzes and propels Peyton. He writes heartfelt letters, rehearses conversations, and seeks forgiveness, but true change begins only when he acknowledges the depth of the harm he’s caused and the complicity he carries.

Felicity’s presence is critical here. She doesn’t offer absolution, but a mirror, showing that pain doesn’t necessarily erase the capacity for decency.

Their relationship marks the first time Peyton begins to build rather than destroy, to confront rather than escape.

Still, Deadbeat resists a tidy resolution. Peyton is not redeemed in a traditional sense; he is still broken, still guilty.

But he is also changed. His final actions—saving Alice, exposing Persico, protecting Skye—stem not from the desire for reward or redemption, but from a place of clarity.

The story suggests that transformation is possible, but only through painful honesty, sustained effort, and a rejection of the illusions we create to justify our darkest choices.