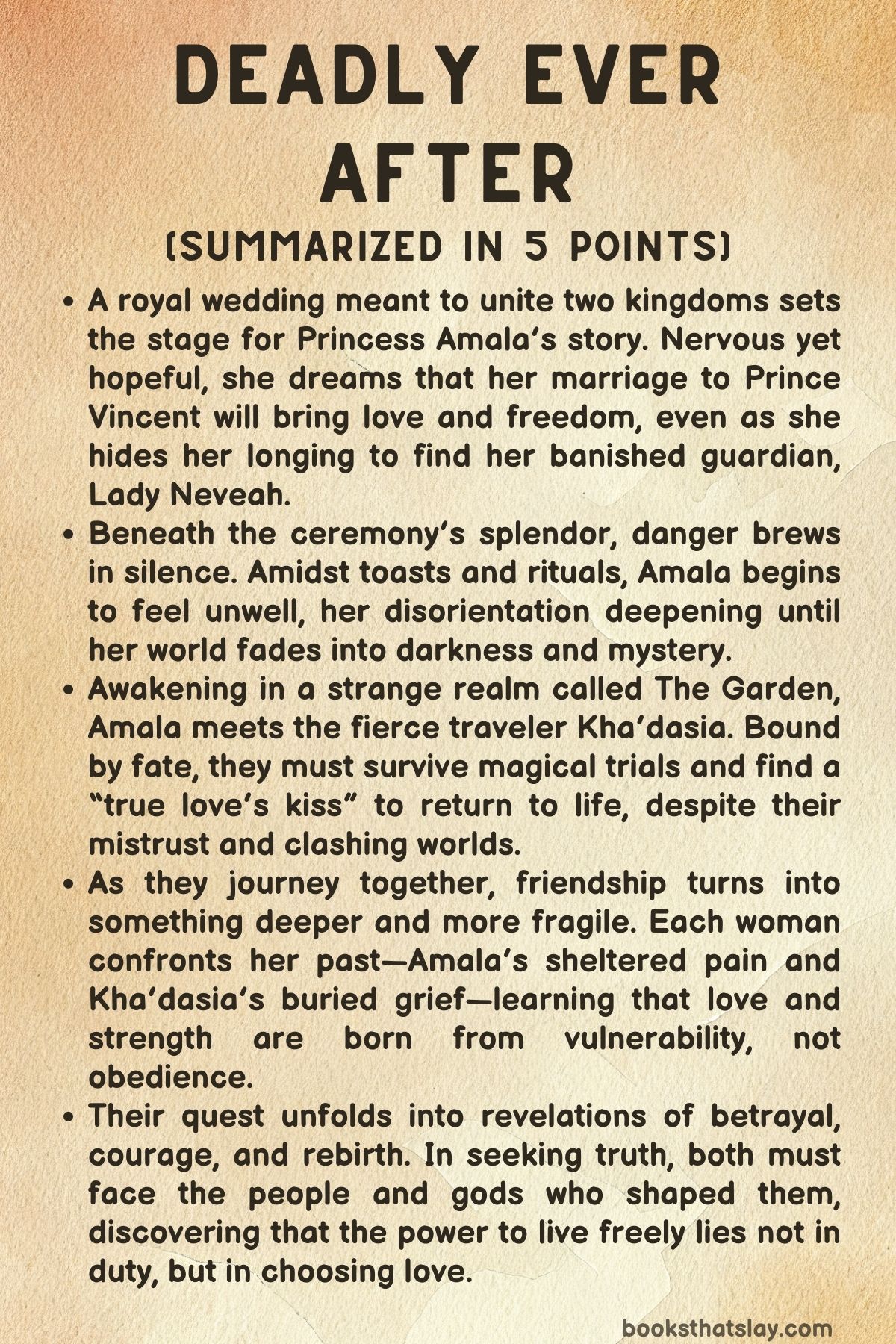

Deadly Ever After Summary, Characters and Themes

Deadly Ever After by Brittany Johnson is a fantasy romance about a princess who discovers that “duty” was never meant to cost her life. Amala of Rosewyn enters a political marriage expecting safety, status, and maybe love—only to be betrayed at the celebration meant to crown her future.

When death nearly claims her, she wakes in a strange in-between realm with its own rules and deadlines. Forced to travel with a sharp-edged survivor named Kha’dasia, Amala must confront lies about faith, family, and her own desires. What begins as survival becomes a choice about who she is—and who she wants beside her.

Summary

Princess Amala of Rosewyn prepares for her wedding to Prince Vincent of Iman while attendants dress her and braid her hair. She writes privately to Khari, Vincent’s younger brother, trying to steady her nerves.

Amala wants this marriage to become more than a political bargain, and she clings to Vincent’s moonstone rose necklace as proof that affection might grow into something real. She also carries a quieter wish: that Vincent will help her find Lady Neveah, the former lady-in-waiting who once cared for her like a mother before being banished.

Tradition forbids anyone from seeing the bride before the ceremony, yet Khari slips into Amala’s room anyway, teasing her and offering comfort. Their warmth ends when Amala’s father arrives.

He treats the breach as a threat to the alliance and a danger to their bloodline, invoking religious fear and public disaster to keep Amala obedient. He destroys her letter, orders her attendants to hide her tears, and makes it clear that her personal happiness does not matter compared to the power the marriage promises.

In the Azalea Courtyard, the wedding proceeds amid extravagant gemstone decor that feels more like a display of wealth than the garden Amala once imagined. The priest leads them through ritual vows and a harsh ceremonial wine.

Vincent kisses Amala with practiced certainty. She responds, wanting to believe in the life ahead, but the moment lands differently than her dreams.

The court celebrates, and the couple moves into a crowded reception where Amala is pulled from one greeting and speech to another.

As the night stretches on, Amala barely eats. Wine is pressed into her hands again and again for toasts until her body begins to sway and her thoughts blur.

Vincent dismisses her discomfort as mild intoxication and kisses her in a way that leaves her feeling cornered instead of cherished. Queen Dominique, Vincent’s mother, draws Amala into a quiet room and steadies her.

In a rare show of softness, Dominique admits she does not open her heart easily, but she values family above all. She insists Vincent cares for Amala and offers support even if the court never fully accepts her.

Starved for maternal comfort after years of isolation and loss, Amala clings to the queen’s reassurance.

Back in the hall, the evening fragments into confusion. Voices warp, faces smear, and Amala struggles to find Vincent.

Then the world lurches: she is dragged into a cold cellar, pain tears through her side, and a shadow looms over her. The last thing she registers is the fact that she has been attacked.

Amala wakes in a bright field wearing a soft lilac dress, unburdened by corsets and ceremony. An older woman tending a garden speaks as if she can hear Amala’s thoughts.

The woman asks a simple question: does Amala want to live or die? Amala remembers the stabbing and panics about Vincent, but the Elder says he is safe for now.

Amala chooses life—and the calm scene ruptures. Storm clouds gather, earth splits, and she falls into a dense forest.

Elsewhere in that forest, Kha’dasia struggles through a looping wilderness where landmarks repeat and escape feels impossible. She is a hardened traveler driven by unfinished business and the ache of someone she lost.

She fights off threats and realizes she is trapped in a place that refuses to let her move forward. When she hears movement nearby, she hunts it down, expecting danger.

Kha’dasia shoves Amala out of harm’s way from a falling tree, then immediately pins her with a blade, demanding answers. Amala, exhausted and frightened, offers little beyond her name and the fact that she has nowhere to go.

Their clash is interrupted by Aledia, a powerful guide who calls the realm “The Garden,” a space between life and death designed to restore people on the edge. Aledia gives them a map and a deadline: five days to reach the Coliseum of the Wilted.

She also sets a cruel condition. To return to life, they must receive a true love’s kiss.

A kiss that is not true will kill them.

Kha’dasia rejects the premise and refuses partnership, until Aledia forces her to witness a vision of her own body dead in the real world, her horse grieving beside her. The proof rattles her.

Night falls, and danger arrives in the form of a massive wolf-like creature with scales and claws. It hunts Kha’dasia through the trees, driving her to fight rather than flee.

She nearly crushes its skull—until she sees its reflection in lake water and recognizes Princess Amala. The “monster” shifts, and Amala stands there, shaken and human.

Kha’dasia is horrified that fear almost made her a killer.

They build a fire and argue, then slowly settle into wary cooperation. Amala admits she never learned to fight; she survived by surrendering and hoping cruelty would end quickly.

Kha’dasia mocks that instinct but cannot ignore Amala’s vulnerability—or her own unexpected urge to protect her. Amala shares memories of being kept confined as a child, sneaking out only in secret, and being scolded by Lady Neveah for risking her life.

Their shared honesty turns into a fragile partnership: Kha’dasia will help Amala reach Vincent, believing his kiss is the safest answer.

An Elder named Hydeia appears and redirects them toward a mountain. The climb is brutal.

Amala slips, panics, and is injured, and Kha’dasia carries her when she can no longer keep pace. The physical closeness stirs feelings neither woman names, but tenderness keeps breaking through Kha’dasia’s hard edges.

At the summit, Hydeia shatters Amala’s worldview by revealing that Ados—the god Amala’s father used to control her—is not real. The creator is Poppy, the Grand Elder, and the Elders guide without controlling human choices.

Amala realizes her father’s cruelty was never holy command, just his own will. Hydeia also hints that Kha’dasia once held a royal life too, a truth Kha’dasia tries to bury.

As they travel, they find a hidden library and the Book of Remembrance, which records their lives. Amala sees proof of her isolation, her bond with Neveah, and signs that her death was not an accident.

Later, sheltering on a storm-tossed ship, Amala opens a trunk and finds a rose-colored compact mirror that shows scenes from the living world when names are spoken. She watches Vincent mourning—then sees another woman join him in bed.

Amala insists grief explains it, while Kha’dasia calls it betrayal. The sea destroys the ship, and they are thrown into the ocean.

Kha’dasia hears her brother Damien’s voice and discovers she can breathe underwater, saving Amala and helping her kill a sea beast with stolen explosives and quick planning.

In a desert and then a dark cave, their emotional walls crack further. Each faces a mirror version of herself: Kha’dasia battles her own self-loathing; Amala is forced to admit how long she accepted suffering and how deeply her feelings for Kha’dasia have grown.

When the illusions break, they reunite bloodied but closer. A music box pulls them into a marble palace that turns out to be Kha’dasia’s past.

She relives the day before Damien’s death, finally facing the grief she never processed. Rage at her parents’ secrecy ignites, and the palace twists into a nightmare that drives them onward.

They reach the Coliseum of the Wilted, only to be told the task is incomplete: there has been no true love’s kiss. A woman named Kiana forces a final test—fight or die.

Amala refuses to harm Kha’dasia. Kha’dasia tries to sacrifice herself, believing Amala deserves life more.

When they collapse, Kha’dasia confesses love but urges Amala back toward Vincent. Amala stops her and chooses Kha’dasia.

They kiss, and the Garden answers: Kha’dasia is saved, fading in light as the magic takes hold.

Amala awakens back in her world inside a glass coffin prepared for her funeral. She breaks free and escapes with Khari’s help.

She learns she was believed dead after a fall, but she knows she was attacked, and she suspects Queen Dominique. When Amala confronts Vincent, he turns violent, trying to finish what was started.

Kha’dasia returns—alive—and saves her. Together with Khari, they storm the funeral and expose Dominique and Vincent.

Under pressure and evidence, Dominique confesses, driven by jealousy and resentment.

Then Amala’s father reveals himself as the deeper traitor. He admits he knew of the plot and used it to seize control, even confessing he killed Lady Neveah.

Amala attacks him but refuses to become a murderer. Chaos collapses the hall, and her father dies in the destruction he helped set in motion.

Amala and Kha’dasia escape the palace, wounded but free.

Days later, they wake under a tree beyond Iman, no longer running from what they feel. They speak honestly, share kisses without fear, and choose a future defined by their own will.

The ground glows and flowers bloom as if the Elders are offering a final blessing. Their torn clothing transforms into regal garments, marking not a perfect ending, but a new life they will shape together.

Characters

Amala

Amala begins Deadly Ever After as a princess trained to treat her own life as a bargaining chip, and that conditioning shows up everywhere in her early choices: she’s nervous but determined to “do this right,” she clings to tradition even when it hurts her, and she keeps trying to manufacture comfort out of symbols like Vincent’s moonstone rose necklace. What makes her compelling is how clearly her softness is not weakness but survival—she has spent years learning to be agreeable in a home ruled by fear, and she mistakes endurance for virtue because that’s what her father rewards.

The turning point in her arc is not simply discovering betrayal and murder; it’s discovering that obedience was never sacred. The Garden forces her to look at the part of herself that kept excusing cruelty as fate, and she eventually names what she wants without apologizing for it: safety, agency, and love that doesn’t demand she disappear.

By the end, Amala’s power looks different than the kind her father worships—she refuses to become a killer even when vengeance would be easy, and that refusal reads as a hard-won identity rather than naïveté. Her love for Kha’dasia becomes the clearest proof of her growth: she stops treating love as a prize awarded for dutiful performance and starts treating it as a living choice that requires honesty, risk, and self-respect.

Kha’dasia

Kha’dasia enters Deadly Ever After as a person built out of motion and defense—sharp, suspicious, and brutally practical—because vulnerability has historically cost her too much. She’s the kind of survivor who trusts her blade more than people, and her first instinct around Amala is to control the situation by dominating it, even when that dominance is fueled by fear and confusion.

Yet her hardness is never hollow bravado; it’s grief made functional. The loss of Damien sits inside her like an untreated wound, shaping her tendency to lash out, to assume abandonment, and to preempt pain by acting like she doesn’t need anyone.

The Garden doesn’t merely test her physically; it corners her emotionally, especially when she’s forced into reflections of herself that articulate what she’s been trying to outrun—self-loathing, guilt, and the terror that love always ends in loss. What ultimately changes her is not a single revelation but repeated moments of care that she doesn’t “deserve” by her own harsh accounting: carrying Amala up a mountain, tending her injuries, calming her fear, and then realizing that protecting someone can be an expression of love rather than a burden.

Her confession in the Coliseum lands with such impact because it’s the first time she stops translating love into sacrifice and allows herself to want something for herself. When she returns to the living world, Kha’dasia still carries her edges, but they’re no longer weapons pointed inward; they become boundaries she can choose, not walls she cannot lower.

Prince Vincent

Vincent in Deadly Ever After is designed, at first, to look like the storybook answer to Amala’s hopes: charming, confident, generous with romantic gestures, and comfortable performing devotion in public. That early polish matters because it shows how easily affection can be staged inside political marriage—Amala reads the necklace and the kiss as promises, while Vincent treats intimacy like something he can take as proof of ownership.

His behavior at the reception, where Amala is steadily pushed past the point of clarity and he still chooses desire over care, reveals a core trait: he prioritizes what he wants in the moment and explains away the consequences. Later, his rapid shift from mourning to replacement love, and then to violence when Amala reappears, reframes him as someone whose loyalty is conditional and whose “love” is tightly tied to control and convenience.

Vincent isn’t written as a complex moral puzzle so much as a mirror for Amala’s early illusions; he represents the kind of romance that looks safe until it is tested, and once tested, it becomes coercion. His defeat matters less as a plot victory and more as a symbolic unmasking—Amala’s happy ending cannot be built on a man who treats her life like an obstacle to be removed.

Khari

Khari functions as a rare, steady warmth inside Deadly Ever After, but his warmth isn’t passive; it’s defiant in a world that runs on intimidation. The fact that he breaks strict wedding tradition to see Amala, jokes with her, and feeds her a stolen cookie isn’t just a cute detail—it shows how he resists the palace’s culture of fear through small acts of human kindness.

His dynamic with Amala carries the tone of chosen family, the kind of relationship where affection is safe because it isn’t transactional, and that safety becomes crucial when her own blood family weaponizes “duty” against her. He also serves as an early warning system: his discomfort with Dominique and his readiness to challenge authority hint that the royal façade is brittle.

Later, when Amala returns to life and Khari helps her flee, his role becomes openly protective, but still grounded in respect—he doesn’t try to decide her story for her, he helps her survive long enough to tell it. Even when violence erupts around them, Khari’s defining trait remains moral clarity: he sees cruelty clearly and refuses to be normalized into accepting it.

Queen Dominique

Dominique is one of the most strategically written figures in Deadly Ever After because she can convincingly perform both comfort and menace, sometimes within the same scene. When she pulls Amala aside at the reception and steadies her, she offers something Amala is starved for: maternal attention that feels private and sincere.

That tenderness is important because it demonstrates how power can weaponize intimacy; Dominique’s “support” positions her as a gatekeeper of belonging, teaching Amala that approval is something to earn. Her stated value—family above all—reads, in hindsight, like the ideology that justifies everything she does, including violence, because she defines family as possession and hierarchy rather than love.

The later confession exposes the engine beneath her composure: envy and resentment disguised as royal duty, specifically her rage at the idea that Amala could “steal” respect that Dominique believes should funnel toward her. Dominique is not simply evil for spectacle; she embodies the way a court can rot behind etiquette, where the most dangerous person may be the one who can cradle you gently while planning your removal.

Her unraveling at the funeral confrontation matters because it strips away the mask and shows what she truly cannot tolerate—loss of control.

King Calvin

King Calvin is the clearest embodiment of tyranny in Deadly Ever After, and what makes him frightening is how personal his tyranny is. He doesn’t only rule; he colonizes Amala’s inner life by teaching her that happiness is irrelevant, that tradition is life-or-death, and that divine punishment will fall if she disobeys—threats designed to make her police herself.

His cruelty is intimate and performative: ripping up her letter, humiliating her tears, and reducing her to a vessel for political merger. Later revelations confirm what his earlier behavior already implies—he believes ends justify any means, including the murder of Lady Neveah and complicity in his daughter’s death, as long as it consolidates power.

His eventual seizure of both kingdoms is the logical extension of the way he has always treated people: as pieces on a board, valuable only when useful. Even his death, crushed by a collapsing chandelier, feels thematically aligned—he is finally destroyed by the very grand spectacle and architecture of rule that he relied on to intimidate others.

Calvin’s presence in the story primarily exists to define what Amala must unlearn: the lie that authority equals righteousness.

King Zahair

Zahair’s role in Deadly Ever After is quieter than Calvin’s, but significant because he represents a different model of kingship—one rooted in legitimacy and stability rather than fear. His devastation when Dominique is exposed reads as genuine, suggesting a ruler who expected loyalty to mean mutual respect, not manipulation.

The fact that he orders Dominique’s arrest once the truth becomes undeniable positions him as someone who can place justice above personal attachment, even when that choice shatters his family. His imprisonment by Calvin underscores the central tragedy of the political world Amala comes from: power does not always reward the decent, and lawful authority can be overthrown by sheer ruthlessness.

Zahair’s character matters because he makes the coup feel like more than palace drama; it’s a takeover of an entire moral order, where cruelty attempts to replace governance.

Lady Neveah

Neveah is less present on the page than other characters in Deadly Ever After, yet she exerts enormous gravitational pull because she represents the first version of love Amala trusted—steady, protective, and genuinely nurturing. Amala’s longing to find her is not nostalgia; it’s a need to reconnect with a time when care did not feel conditional.

The banishment creates a wound that shapes Amala’s hunger for maternal comfort later, which is why Dominique’s brief kindness lands so powerfully—and why that kindness becomes such an effective trap. When it is revealed that Neveah was killed, the loss reframes Amala’s childhood not just as lonely, but actively stolen; the one person who tried to guard her softness was eliminated by the same system that demanded her obedience.

Neveah therefore becomes a moral reference point in the story: she symbolizes the life Amala might have lived if love had been allowed to protect her instead of being punished for it.

Aledia

Aledia appears in Deadly Ever After as an agent of cosmic rule-setting, and her impact comes from how she disrupts the characters’ assumptions about fairness and control. She is powerful, calm, and almost playful in how easily she neutralizes violence, which immediately signals that The Garden is not a place where brute force is the highest language.

By explaining the five-day limit and the condition of the “true love’s kiss,” she frames their ordeal as an emotional trial disguised as a survival quest. Importantly, she refuses to comfort them the way a benevolent rescuer might; instead, she gives them information and lets them collide with the consequences, implying that growth requires choice rather than rescue.

Her vision to Kha’dasia—showing the reality of death—pushes Kha’dasia from denial into engagement, turning the quest into something she must actively claim. Aledia’s function is to introduce the story’s governing philosophy: love is not a decorative reward at the end of pain, but a transformative force that demands honesty.

Hydeia

Hydeia’s role in Deadly Ever After is that of a blunt spiritual disruptor—less mystical comfort, more surgical truth. She challenges the protagonists not just on direction but on worldview, forcing them to confront the possibility that the religious framework used to control Amala is fabricated.

By naming Poppy as the true creator and denying Ados, Hydeia doesn’t merely reveal lore; she detonates Amala’s inherited guilt and rewrites the meaning of her suffering, making it clear her father’s cruelty was a choice, not destiny. Hydeia also pokes at Kha’dasia’s identity by revealing her own royal origins, which matters because it threatens Kha’dasia’s carefully constructed self-image as someone who belongs nowhere and owes nothing.

Her insistence that love, trust, and vulnerability are the real keys reframes their partnership from convenience to necessity, pushing them toward the emotional risk both resist. Hydeia’s presence therefore acts like a philosophical checkpoint: she forces both women to consider that freedom requires them to stop outsourcing their worth to authority, bloodline, or doctrine.

Kiana

Kiana arrives in Deadly Ever After at the moment when emotional truth can no longer be postponed, and she embodies the story’s harshest test: the demand that love be proven under threat of loss. Her insistence that the Coliseum marks completion while simultaneously declaring that Amala has failed creates a cruel paradox that forces action—no more traveling, no more bonding slowly, no more pretending the kiss can wait.

By conjuring swords and turning the situation into an apparent duel to the death, Kiana externalizes the internal conflict both women have carried: the fear that choosing love will destroy someone. Whether she is seen as an enforcer, a judge, or a ritual figure, her narrative purpose is to compress the story into a final decision where honesty becomes survival.

In that sense, Kiana is less a fully domestic character and more a symbolic mechanism—she transforms the unspoken into an ultimatum, making the eventual confession and kiss feel earned rather than convenient.

Grand Elder Poppy

Poppy represents the thematic heart of Deadly Ever After, not because she is constantly present, but because she articulates what the entire ordeal was designed to teach. When she appears after the kiss, she validates love as the strongest magic, but she also frames love as liberation rather than possession—an important distinction given how many characters have tried to claim Amala as property.

Her “second chance” to Amala is not framed as a reward for obedience; it’s permission to live truthfully, to hold softness and strength together without shame. Poppy’s presence also redefines the Elders’ role: guides rather than puppeteers, emphasizing that the protagonists’ growth came from their choices, not divine intervention.

The final transformation—flowers blooming, clothing shifting into regal garments—lands as symbolic affirmation of rebirth, but the deeper gift is ideological: Amala and Kha’dasia are no longer trapped inside other people’s scripts for them. Poppy becomes the voice of that freedom, marking the end of survival-as-submission and the beginning of life-as-authorship.

Damien

Damien’s influence in Deadly Ever After is profound despite his limited “present-time” involvement, because he is the central grief that shaped Kha’dasia long before The Garden. He exists in her mind as both comfort and unfinished goodbye, and that unfinished goodbye is what fuels her anger, her distrust, and her compulsion to keep moving—if she stops, she has to feel.

When Kha’dasia relives the day before his death, the story reframes her toughness as mourning that never got closure, and his gentle acceptance becomes a counterweight to her self-punishment. He doesn’t demand that she stay or suffer to prove love; he recognizes her survival as already meaningful, which exposes how cruelly she has judged herself.

Damien’s symbolic role is to show Kha’dasia the version of love that does not control, bargain, or manipulate—love that releases. That memory becomes one of the emotional stepping-stones that makes it possible for her to accept love again with Amala.

Butterscotch

Butterscotch, in Deadly Ever After, is a small but striking embodiment of loyalty and innocence amid surreal violence. The vision of the grieving horse anchors Kha’dasia’s death in something raw and real—an animal’s uncomplicated mourning that contrasts with the political, performative grief in royal spaces.

Butterscotch also reinforces Kha’dasia’s life before The Garden as tangible and grounded; she is not only a fighter in an abstract quest, but a person who had a companion, habits, and attachments. In a story where love is repeatedly tested, the horse quietly represents devotion without calculation, reminding the reader that care can exist without strategy.

Themes

Love and Transformation

Love in Deadly Ever After extends far beyond romantic affection—it becomes a force of spiritual and moral transformation. The novel begins with Amala’s naïve, idealized belief in her arranged marriage to Prince Vincent.

Her love at this stage is shaped by duty, fantasy, and political necessity. Yet as her journey progresses through death and rebirth, that same concept evolves into something raw, redemptive, and self-defining.

The Garden, the liminal space between life and death, serves as the crucible in which her understanding of love is reformed. Her relationship with Kha’dasia, forged through shared suffering, trust, and sacrifice, stands in stark contrast to the hollow love she once attached to Vincent.

Their bond is not built on appearance, expectation, or social convenience but on mutual recognition of pain and the courage to face it. The “true love’s kiss” that ultimately saves them both is not a reward for compliance but an awakening—proof that love is strongest when it transcends tradition, gender, and even mortality.

By the end, love becomes synonymous with freedom; it no longer belongs to royal decrees or divine law but to personal choice. This transformation from possession to partnership marks the emotional and moral axis of the novel, illustrating that love, in its truest form, dismantles illusion and redefines the boundaries of the self.

Power, Patriarchy, and Rebellion

Throughout Deadly Ever After, power operates as a suffocating hierarchy, one that enforces obedience under the guise of divine will. Amala’s father and Queen Dominique both embody systems of control rooted in gender and authority—one through religion, the other through political manipulation.

Amala’s early life is dictated by male dominance, where her worth is reduced to her utility in alliances, and even her emotions are treated as liabilities. Her father’s invocation of Ados, the false god, functions as a tool to sanctify his cruelty.

This divine justification reflects the broader critique of how institutions—be they monarchies or religions—use faith to reinforce patriarchal order. Yet the revelation from Elder Hydeia that Ados is not real dismantles that power’s foundation.

Amala’s defiance thereafter is not just personal rebellion but a reclamation of truth against centuries of imposed lies. Kha’dasia, too, fights against structures that dictated her identity—a fallen princess turned survivor who rejects the nobility that betrayed her.

Together, the women expose the rot beneath royal grandeur, proving that liberation demands both external resistance and internal courage. By confronting their fathers, queens, and gods alike, they become architects of their own authority, embodying rebellion not as chaos but as restoration of justice and selfhood.

Identity and Self-Discovery

Amala’s journey from sheltered princess to reborn survivor encapsulates the theme of identity as a dynamic, painful evolution. Her story begins in isolation, her sense of self molded entirely by expectation and confinement.

She is defined by others—her father’s ambitions, Vincent’s promises, her people’s prayers. Yet the trauma of her murder and her passage through the Garden strip away these external definitions, forcing her to confront who she is when stripped of title and privilege.

Kha’dasia’s parallel struggle adds a mirror dimension; she, too, has fled an identity defined by nobility and guilt, carrying the weight of her brother’s death and her own perceived failures. The Garden becomes a literal and metaphorical landscape of mirrors, where both women must confront their reflections—not as vanity, but as confession.

The mirror scenes crystallize this theme: identity cannot be inherited or assigned; it must be claimed through acknowledgment of one’s contradictions. When Amala finally rejects her father’s ideology and claims her agency, and when Kha’dasia forgives herself and accepts love, both women transcend the roles imposed upon them.

Identity, in the novel, emerges not as a static truth but as an act of continual self-definition, earned through honesty and empathy.

Death, Rebirth, and the Cycle of Renewal

Death is not an ending in Deadly Ever After but a threshold for transformation. From the moment Amala is stabbed on her wedding night, the narrative reframes mortality as a state of transition rather than termination.

The Garden itself symbolizes this liminal existence—a place where life and death coexist, where choices carry metaphysical consequence. Each trial the protagonists endure mirrors the stages of renewal: denial, confrontation, sacrifice, and rebirth.

The journey through forests, mountains, oceans, and deserts parallels spiritual resurrection, dismantling the illusion that death erases meaning. For Kha’dasia, confronting her brother’s death allows her to reconcile the living and the lost, while for Amala, resurrection grants her not just breath but awareness—the courage to live authentically.

The final sequence, in which they awaken under a blooming tree as flowers rise from the earth, affirms the novel’s cyclical vision: every ending births a beginning. Death, then, becomes the price of awakening, and rebirth becomes a moral choice—to live truthfully after having faced the darkness.

This theme ties the novel’s fantasy elements to universal questions about forgiveness, endurance, and the human capacity to change.

Faith, Truth, and the Illusion of Divinity

Religion in Deadly Ever After is portrayed as both a weapon and a delusion. Amala’s world operates under the shadow of Ados, a god invoked to justify hierarchy, punishment, and fear.

Her father’s invocation of divine wrath to control her reflects how faith can become a mechanism of obedience rather than enlightenment. The revelation from Elder Hydeia that Ados is a fabrication and that the true cosmic balance lies with the Elders—particularly the nurturing, truth-bearing Poppy—upends the moral order that once ruled Amala’s life.

The discovery dismantles not faith itself but blind faith, replacing it with understanding and personal spirituality. By confronting this deception, Amala learns that the divine does not dwell in authority but in empathy, love, and moral choice.

Faith, therefore, transforms from submission to insight. The story’s moral arc reclaims the sacred from the corrupt, suggesting that truth is the only form of divinity worth worshiping.

This dismantling of false gods resonates beyond its fantasy setting, critiquing any system that uses sanctity to sustain oppression while reaffirming belief as a deeply human, self-guided force.