Death in Venice Summary, Characters and Themes

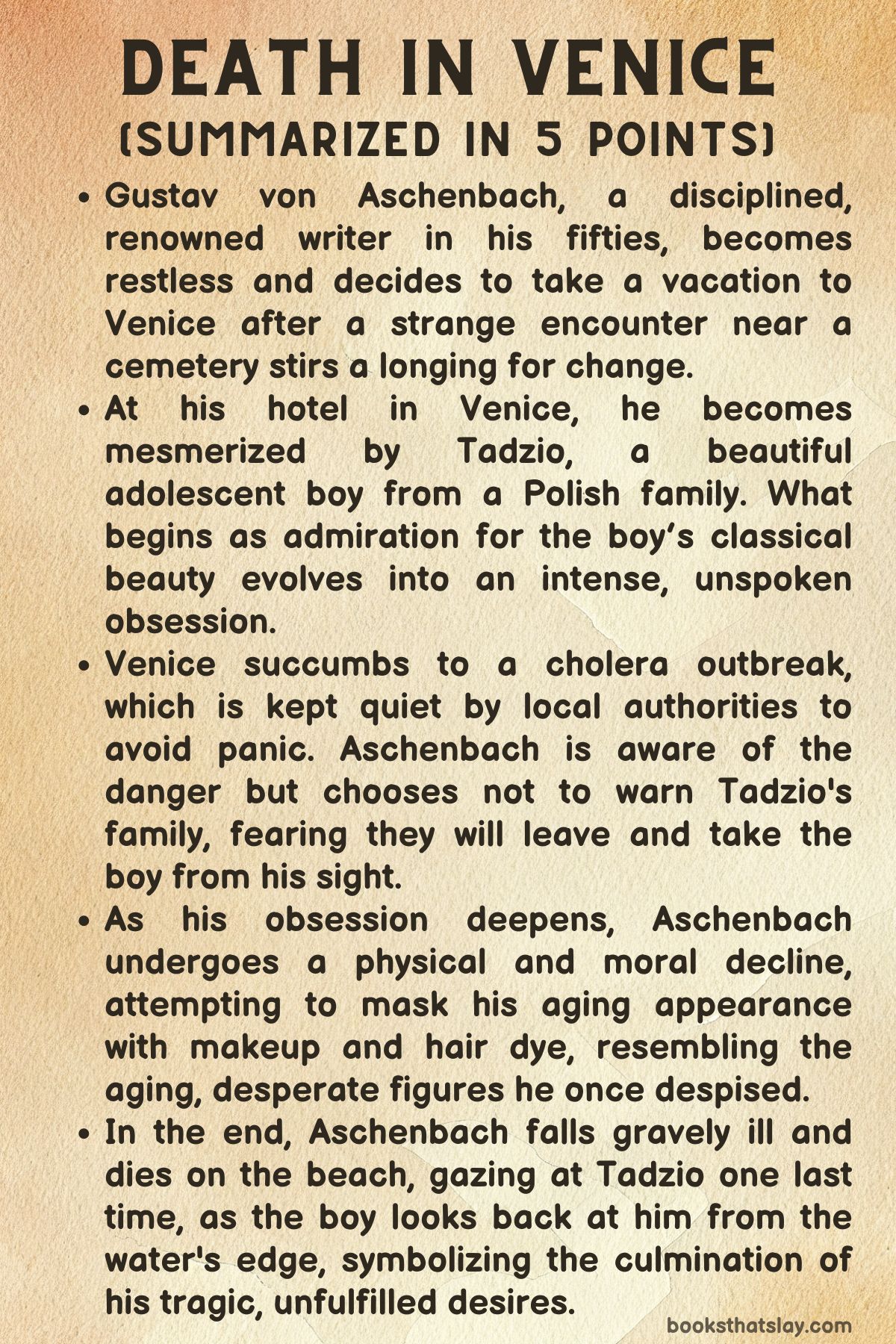

Death in Venice, written by Thomas Mann and published in 1912, is a novella that delves into the themes of beauty, obsession, and moral decay. Set against the backdrop of a mysterious, cholera-ridden Venice, the story follows Gustav von Aschenbach, a disciplined and celebrated writer, who becomes captivated by the youthful beauty of a boy named Tadzio.

As his obsession deepens, Aschenbach’s once-ordered life spirals into inner turmoil, mirroring the city’s gradual descent into sickness. The novella explores the conflict between desire and restraint, art and decay, ultimately leading to Aschenbach’s tragic demise.

Summary

The protagonist, Gustav von Aschenbach, is a distinguished author in his fifties who has recently been granted a title of nobility. Renowned for his strict, ascetic lifestyle and dedication to his craft, Aschenbach is a widower who has poured his passion entirely into his art.

However, when we first meet him, he is feeling unusually restless. During a stroll near a cemetery, a strange encounter with a rough-looking foreigner stirs something within him. This brief but unsettling moment, accompanied by a vision of an exotic, threatening landscape, ignites a desire for travel.

After an aborted attempt to visit Pula, Aschenbach decides on Venice, drawn to the city’s allure. Upon arrival at the luxurious Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido, he notices a strikingly beautiful adolescent boy among a family of Polish tourists. The boy, Tadzio, dressed in a sailor suit, captivates him.

Aschenbach initially interprets his fascination with Tadzio as an admiration for idealized beauty, reminiscent of classical art. Though he plans to leave Venice soon after, the oppressive summer heat and his growing attachment to Tadzio cause him to stay.

What starts as a seemingly innocent admiration quickly transforms into something more intense. Aschenbach spends his days watching Tadzio at the beach, following him through the streets of Venice, and becoming consumed by the boy’s every movement.

When Tadzio smiles at him one day, it feels like a moment of mutual recognition, further fueling Aschenbach’s obsession. Yet, even as his feelings grow stronger, they remain silent and unspoken.

Meanwhile, Venice is quietly descending into crisis. There are warnings about an illness spreading through the city, but Aschenbach ignores the signs, even as the pungent smell of disinfectant fills the air.

The disease, it turns out, is cholera, though the authorities deny its severity to avoid scaring away tourists. Aschenbach considers warning Tadzio’s family, knowing they would likely leave if they understood the danger. However, he chooses not to, unwilling to lose sight of the boy.

As his obsession deepens, Aschenbach begins to deteriorate, both physically and mentally. He tries to preserve his fading youth by dyeing his hair and using makeup, becoming an almost grotesque version of the elderly man he had once scorned on the journey to Venice.

He continues to follow Tadzio through the city, even as Venice grows hotter and more oppressive, mirroring his own inner disintegration.

Finally, as Tadzio’s family prepares to depart, Aschenbach, weakened and ill, makes his way to the beach one last time. Tadzio, after a brief altercation with another boy, walks to the water’s edge, glancing back toward Aschenbach as if beckoning him. But Aschenbach, trying to rise, collapses in his chair.

His body is discovered shortly afterward, his obsession having consumed him entirely.

Characters

Gustav von Aschenbach

Gustav von Aschenbach is the central character of Death in Venice and represents a man of rigid discipline and moral austerity. A celebrated author ennobled for his artistic achievements, Aschenbach has led a life marked by self-control and intellectual rigor, suppressing all personal desires in favor of artistic creation.

His early widowhood has deepened his sense of isolation and detachment, qualities that further emphasize his internal struggles as he seeks to balance his repressed emotions with his public persona as a figure of high culture. Aschenbach’s character is defined by a profound conflict between his disciplined outer self and the awakening of his inner desires.

The novella captures his psychological unraveling as his admiration for the young Polish boy, Tadzio, intensifies into an unhealthy obsession. His initial fascination with Tadzio’s beauty as an ideal of aesthetic perfection evolves into a more deeply troubling attraction, which disrupts his previously rigid sense of self-control.

He attempts to mask the reality of his deteriorating emotional state by indulging in superficial efforts to regain youth, such as dyeing his hair and applying makeup—acts that reflect his descent into a state of self-delusion. Aschenbach’s pursuit of beauty, initially framed as an intellectual and artistic quest, eventually exposes his vulnerability to the irrational and the Dionysian, leading to his moral and physical downfall.

The journey from intellectual distance to obsessive infatuation reveals Aschenbach’s struggle with his repressed sensuality, which manifests not only in his obsession with Tadzio but also in his increasingly poor decision-making. His refusal to leave Venice, even after becoming aware of the cholera epidemic, illustrates his growing detachment from rationality.

In the end, Aschenbach’s collapse into death is symbolic of his complete surrender to passion and decay, marking the tragic conclusion of a life that had previously been devoted to the pursuit of order and form.

Tadzio

Tadzio is the beautiful Polish boy with whom Aschenbach becomes obsessed. Described as being around 14 years old, Tadzio is presented as an almost ethereal figure, representing classical beauty in its purest form.

His physical appearance, with its delicate features and resemblance to a Greek sculpture, makes him an object of aesthetic admiration, and in Aschenbach’s mind, he comes to symbolize the Platonic ideal of beauty. Tadzio’s character, though central to the novella, remains largely enigmatic.

He does not speak directly in the story, and most of his significance comes from Aschenbach’s perception of him rather than any direct insight into his personality. Tadzio represents an unattainable ideal, a symbol rather than a fully realized human being.

He embodies youth, beauty, and innocence, which stand in contrast to Aschenbach’s aging body and his repressed desires. Despite the fact that Tadzio is an object of admiration for Aschenbach, the boy remains somewhat detached, only offering fleeting glances and smiles that intensify the writer’s obsession.

In the final scenes, Tadzio’s behavior becomes more symbolic, particularly during the moment when he stands at the edge of the sea and looks back at Aschenbach. This act, interpreted by Aschenbach as a beckoning, reflects the unattainable and elusive nature of beauty and desire, which Aschenbach strives to follow but ultimately cannot reach.

Tadzio remains an inscrutable figure, whose beauty captivates but also leads Aschenbach to his downfall, representing both the allure and the destructiveness of unchecked obsession.

The Polish Family

The Polish family, of which Tadzio is a part, serves as a background to Tadzio’s character and further emphasizes Aschenbach’s position as an outsider. The family is aristocratic, well-mannered, and seems largely unaware of the growing obsession Aschenbach harbors for Tadzio.

The family members, especially Tadzio’s mother, represent a certain ideal of decorum and high-class respectability, which only heightens the tension between Aschenbach’s hidden desires and the appearance of respectability he tries to maintain. Tadzio’s elder sisters, described as severely dressed and nun-like, provide a sharp contrast to Tadzio’s beauty and youth.

Their presence reinforces the idea that Aschenbach’s attraction to Tadzio is unusual and forbidden, as the boy stands out in stark contrast to the rest of his family. The family, though silent and passive, creates the social context in which Aschenbach’s feelings seem more inappropriate and dangerous.

The Red-Haired Men

Throughout Death in Venice, Aschenbach encounters several red-haired men, who appear to function as symbolic figures representing danger, foreignness, and death. The first red-haired man, encountered near the cemetery at the start of the novella, ignites Aschenbach’s journey toward Venice.

His rough, foreign appearance and aggressive stare disturb and stimulate Aschenbach, foreshadowing the unsettling experiences that will follow. The second red-haired man, the gondolier, furthers this sense of unease.

He appears skull-like, emphasizes his outsider status by rowing Aschenbach without permission, and evokes themes of death and the passage into an underworld. His presence on the gondola evokes imagery of Charon, the ferryman from Greek mythology who transports souls to the land of the dead, reinforcing the idea that Aschenbach’s journey to Venice is also a journey toward his own demise.

The third red-haired man, a street singer, performs bawdy and Dionysian songs, which contrast sharply with Aschenbach’s usual tastes. His performance serves as a symbol of the seductive power of the irrational, drawing Aschenbach further into his descent into obsession and irrationality.

Each red-haired figure progressively leads Aschenbach closer to his physical and moral deterioration, reinforcing the themes of decay and inevitable death.

The Barber

The barber plays a relatively minor but symbolically important role in Aschenbach’s transformation. As Aschenbach becomes more fixated on his appearance and youth in his pursuit of Tadzio, the barber represents the external forces that encourage his delusion.

Persuading Aschenbach to dye his hair and apply makeup, the barber helps Aschenbach physically transform into the very image of the old man he once found so repulsive on the ship. The barber’s role is crucial in symbolizing Aschenbach’s futile and desperate attempts to hold on to youth and vitality.

His encouragement of Aschenbach’s vanity serves as a manifestation of the superficiality of Aschenbach’s obsession, illustrating the extent to which Aschenbach is willing to deceive himself in order to pursue the ideal of beauty represented by Tadzio. The grotesque transformation marks the final stage of Aschenbach’s descent into self-destruction.

Themes

The Eros-Thanatos Dichotomy and the Obsession with Youthful Beauty

At the core of Death in Venice lies the tension between Eros (the life instinct, symbolized by desire and beauty) and Thanatos (the death instinct, symbolized by decay and mortality). Gustav von Aschenbach, a disciplined, ascetic man who has lived a life of strict intellectualism and artistic refinement, is initially repelled by disorder and aging, as seen in his disgust towards the elderly man on the boat who attempts to appear youthful.

Yet, Aschenbach finds himself irresistibly drawn to Tadzio, whose physical beauty represents a pure, unattainable form of youth, vitality, and artistic ideal. Aschenbach’s growing obsession with the boy corresponds with his gradual embrace of death, culminating in his collapse on the beach as he gazes upon Tadzio for the final time.

This relationship between Eros and Thanatos becomes increasingly pronounced as the novella progresses. Aschenbach’s passion for Tadzio, which he initially interprets as an artistic appreciation of beauty, transforms into a corrosive infatuation that consumes his entire being.

In a sense, Aschenbach’s death is not merely physical but the death of his rational self, consumed by an unfulfilled longing for unattainable youth and beauty. His bodily collapse on the beach mirrors the crumbling of his moral and intellectual faculties, highlighting Mann’s exploration of how the pursuit of beauty can lead to personal destruction when divorced from moral restraint.

The Dionysian vs. Apollonian Conflict

Mann’s novella vividly depicts the struggle between the Apollonian (order, rationality, self-discipline) and the Dionysian (chaos, desire, sensuality) forces within the human psyche. Aschenbach, at the beginning of the novella, embodies the Apollonian ideal. He is a model of restraint and intellectual rigor, an artist who has built his success on self-discipline and denial of base instincts.

His life is carefully constructed around the values of structure, morality, and classical beauty. However, his journey to Venice initiates a profound transformation in which the Dionysian forces, symbolized by Tadzio’s youthful allure and Venice’s humid, decaying atmosphere, begin to erode his defenses.

As Venice succumbs to the chaos of the cholera epidemic, so too does Aschenbach’s Apollonian self. The cholera outbreak symbolizes the city’s descent into a chaotic, Dionysian underworld where beauty, desire, and death intermingle.

As Aschenbach’s obsession with Tadzio deepens, he experiences a vivid, dream-like vision filled with orgiastic imagery, a clear manifestation of his submission to Dionysian impulses. The collapse of reason and self-control is complete when Aschenbach allows himself to be transformed into a grotesque parody of youth, dyeing his hair and painting his face like the elderly man he had once despised.

Mann’s portrayal of this conflict suggests that an over-reliance on rationality, devoid of sensual experience, may lead to its eventual subversion by primal forces lurking beneath the surface.

Decadence and the Fall of Civilizations with Venice Being a Metaphor for Decay

Venice, as depicted by Mann, is not merely a picturesque setting for Aschenbach’s internal drama but a symbol of decay and moral degradation. It serves as a broader allegory for the collapse of civilizations. The city, once a symbol of cultural and economic prosperity, is now depicted as a place of rot, disease, and corruption.

This setting mirrors Aschenbach’s own spiritual and physical decline. Mann draws on Venice’s rich historical connotations as a city teetering on the edge of ruin to enhance the sense of inevitable decay that permeates the novella.

The cholera epidemic, initially downplayed by the authorities and unnoticed by the tourists, serves as a stark metaphor for how societies, just like individuals, can be consumed by internal rot despite outward appearances of beauty and vitality. As Aschenbach walks through Venice’s labyrinthine streets, filled with the stench of disinfectants, he becomes aware that the city is suffocating under the weight of its own corruption.

This is further symbolized by Aschenbach’s own disintegration. As he abandons his once-sterile life of intellectual rigor for a feverish obsession with Tadzio, his pursuit mirrors Venice’s descent into chaos. Mann suggests that all civilizations, like individuals, are vulnerable to their own latent desires and suppressed instincts, which, when uncontained, can lead to their undoing.

Art, Aestheticism, and Moral Ambiguity

Death in Venice also functions as a meditation on the artist’s relationship with beauty and the ethical ambiguities inherent in the aesthetic pursuit. Aschenbach’s passion for Tadzio is consistently framed in terms of the classical ideals of beauty, as the boy’s form evokes images of Greek statues and divine perfection.

However, Mann complicates the notion of aesthetic appreciation by exposing how Aschenbach’s artistic gaze blurs the boundaries between disinterested admiration and corrupt desire. In this sense, the novella interrogates the extent to which aestheticism can be separated from moral responsibility, particularly when it crosses into the realm of obsession and voyeurism.

Aschenbach’s internal rationalizations of his behavior, couched in the language of artistic transcendence, serve to highlight this moral ambiguity. He convinces himself that his love for Tadzio is an expression of his devotion to beauty and art, but his actions—stalking the boy, whispering declarations of love to himself—suggest otherwise.

Mann portrays the artist’s quest for beauty as inherently perilous, an endeavor that can lead to both creation and destruction. This ambivalence reflects Mann’s critique of fin-de-siècle aestheticism, particularly the idea that the pursuit of beauty can be justified at any cost.

In Death in Venice, the artist’s quest for beauty becomes entangled with vanity, desire, and self-deception, raising uncomfortable questions about the ethical limits of artistic creation.

The Plague and the Social Illusions of Stability

The cholera epidemic in Venice operates as a powerful symbol of the fragility of social order and the illusions of stability that often mask underlying chaos. Throughout the novella, Venice’s authorities downplay the threat of disease, maintaining an illusion of safety and normalcy for the tourists.

This deliberate concealment of the epidemic speaks to the broader theme of societal denial in the face of existential threats. Just as Aschenbach refuses to confront the true nature of his obsession with Tadzio, the city of Venice ignores the growing plague that is ravaging its population, preferring to maintain a façade of order and beauty.

The plague also parallels Aschenbach’s personal decline, suggesting that social decay and individual moral decay are intertwined. The novella explores how societies, like individuals, construct illusions of control and stability in the face of impending disaster.

This theme resonates beyond Venice, reflecting broader concerns about modernity and the fragility of cultural institutions in the face of irrational forces. Whether they be disease, desire, or moral corruption, Mann’s Venice is not just a physical space but a psychological one, where the latent forces of destruction ultimately erupt, consuming both the city and Aschenbach.