Discontent by Beatriz Serrano Summary, Characters and Themes

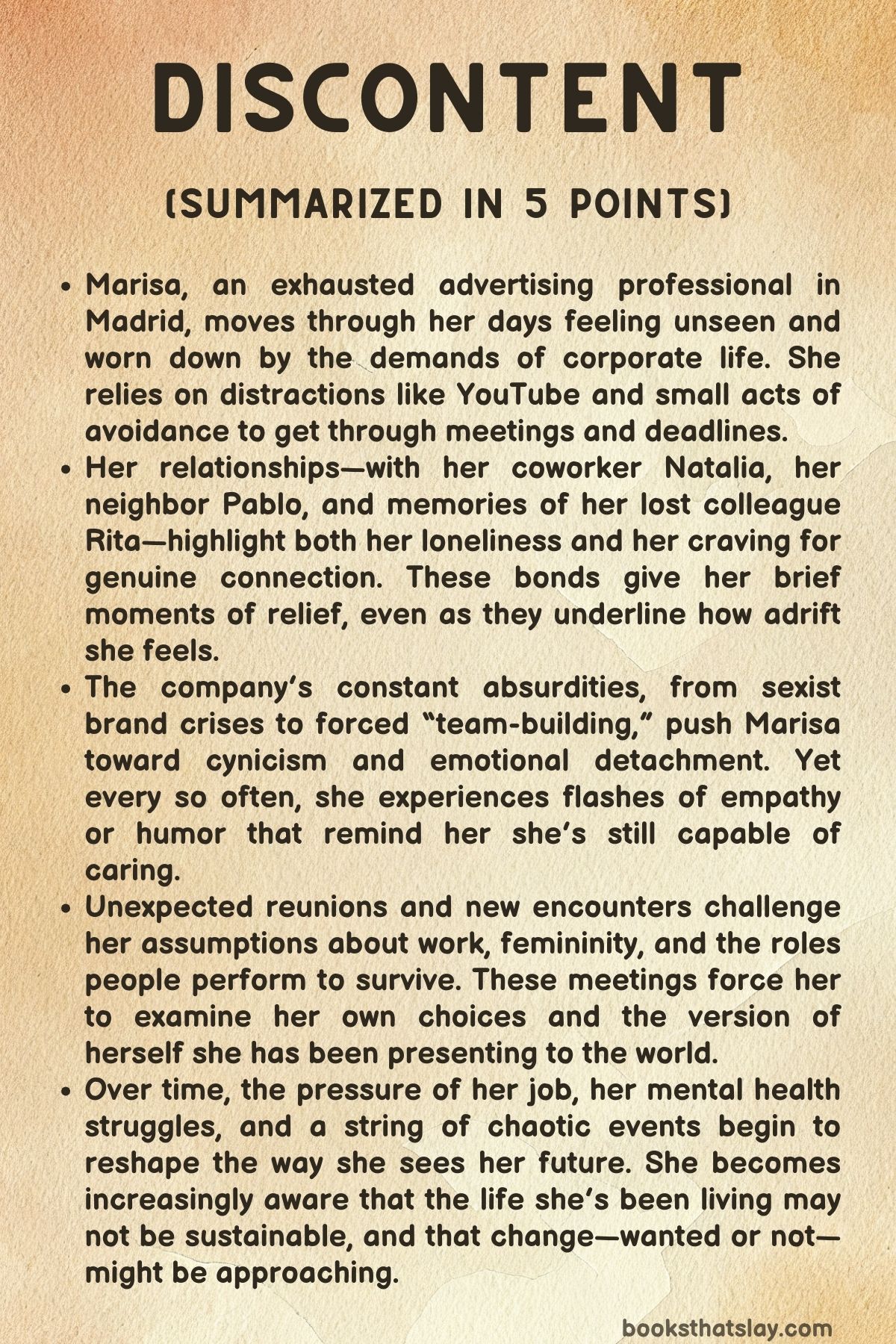

Discontent by Beatriz Serrano is a sharp, darkly funny portrait of a woman pushed to the edge by modern work culture, digital overstimulation, and the quiet fractures of loneliness. Through the eyes of Marisa, an advertising professional in Madrid, the book explores burnout, shallow corporate rituals, and the longing for real connection in a world where everyone is performing.

Serrano blends humor and despair with precision, highlighting the contradictions of a life spent selling fantasies while struggling to believe in anything. The result is a candid, unsettling, and often surprisingly tender account of a woman trying to understand what a livable life could look like.

Summary

Discontent follows Marisa, a weary creative strategist in a Madrid advertising agency whose daily life feels like an exhausting performance she can barely maintain. From the outset, she compares herself to an internet case of supposed captivity—Marina Joyce—imagining that only particularly attentive observers could detect her own decline under the surface.

Each workday begins with cheery but empty video calls, forced seasonal planning, and the routine of pretending to care about campaigns she finds meaningless. She often distracts herself with doodles or YouTube searches while strategically offering fake deadlines to manipulate expectations.

By the end of every meeting, she feels drained, as though she has been silently asking for help no one can hear.

Her reflections reveal eight years of climbing the ranks in advertising, despite feeling she lacks the spark others assume she has. She understands the industry as a system built on manufacturing desires and insecurities, yet she has also been shaped by the very illusions she helps promote.

She teaches in a master’s program, fully intending to appropriate her students’ best ideas for her own presentations, and relies on her hardworking junior Natalia to absorb most of the practical labor, knowing Natalia’s eagerness will keep her compliant.

Her private office—secured with a flimsy argument about equality and workspace independence—serves mostly as a refuge for her true passion: binge-watching YouTube. She slips between conspiracy videos, tutorials, and random bits of internet culture until work intrudes again.

After responding perfunctorily to a call about an eyelash curler campaign, she indulges in schadenfreude by mocking a disastrous flash-mob proposal online. Needing escape, she leaves for the Prado Museum, where Ativan steadies her enough to appreciate Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

She finds comfort in the painting’s depiction of human possibility and returns home calmer.

Her evening is spent answering emails, dreading an upcoming company retreat full of motivational theatrics, and considering buying MDMA to endure it. She sits on her terrace thinking about her casual relationship with her neighbor Pablo.

After a nap and a small ritual of grooming, she invites him over. They talk about daily monotony, the subtle manipulations of dating culture, and their shared sense that life moves in repetitive loops.

Their intimacy offers temporary relief, but she wakes alone the next morning and resumes her regular routine.

Work brings more absurdities: a dispute over stolen coffee capsules, another meeting about creative tasks, and then the sudden announcement of a minute of silence for Rita, a former colleague whose death shocked Marisa deeply. The mention of Rita triggers an internal fracture.

Rita had been a rare source of honesty and intellectual companionship at the agency, someone who recognized Marisa’s panic attacks and encouraged her to seek help. After Rita’s death—rumored to be a suicide—the office quickly moved on, leaving Marisa to privately take Rita’s belongings home, where they remained untouched in a box she could not face.

Amid these emotional undercurrents, Marisa is asked to help select speakers for the retreat. Her boss’s clumsy attempt at gender equality leaves her irritated, but she still plays along and proposes options even she knows the company won’t choose.

Exhausted, she leaves work early and wanders through a 24-hour supermarket, filling her basket with indulgent groceries for a solitary feast. At home, she cooks, watches more YouTube, fields a perfunctory call from her mother, and medicates herself to sleep.

The next day begins with artificial confidence but quickly descends into a “crisis cabinet” meeting over a sexist tweet posted by a client’s brand during a cooking show. Marisa refuses to let the most junior employee take the blame and writes an apology that blends acknowledgment with empty corporate positioning—exactly what the client wants.

Natalia is thrilled; Marisa feels only fatigue. Seeking a break, she takes herself to an upscale Japanese restaurant, where she unexpectedly meets Elena, her closest friend from university, now transformed, glamorous, and self-possessed.

They reconnect instantly and agree to meet that evening.

Their reunion becomes a night of heavy drinking, confessions, and revived intimacy. Elena describes her unconventional life—abandoning traditional work, doing beauty treatments, and surviving through arrangements with wealthy men.

She insists her choices are deliberate acts of agency. Marisa is both fascinated and unsettled, aware of how different their paths have become.

Elena eventually takes Marisa home, undresses her gently, removes her makeup, and comforts her like she used to. After Elena leaves, Marisa spirals into panic and finally opens the box of Rita’s belongings.

Drawings, notebooks, and a portrait of herself reveal Rita’s intense interior world. The shock destabilizes Marisa further, and she turns again to YouTube to soothe herself to sleep.

Hungover the next morning, she skips work and orders delivery food. She forces herself to assemble ideas for a Christmas campaign using her students’ work, feeling vampiric as she consumes their creativity.

Pablo visits that evening, bringing beer. They talk about her impulsive plan to travel to Fuerteventura and about the awkward moment he shared with Elena when both women drunkenly tried to enter his apartment the night before.

The night ends quietly, offering her a moment of stability.

Friday arrives: the company retreat she has long dreaded. She boards the bus with coworkers she finds impossible to relate to, craving a different life.

At the forested retreat site, management opens with a forced tribute to Rita, which Marisa experiences as painful hypocrisy. Her colleagues say empty things while ignoring their role in Rita’s isolation.

The day’s main activity is paintball. Marisa is assigned to a team led by Maika, a hypercompetitive coworker.

As they navigate the forest, Marisa struggles with exhaustion and emotional overload. She hides behind a pallet, smokes a joint, and spirals into a panic attack.

With no medication and no emotional anchor, she imagines confessing her true pain to her mother. After slowly recovering, she attempts to rejoin the game but accidentally shoots Maika, who retaliates by firing directly at her head in a moment of rage.

When Maika sees Marisa’s distress, she softens and calls for help.

Emilio, a young paintball monitor, takes charge. He immediately recognizes that Marisa is high and gently guides her back to safety, promising juice and food.

In her hotel room, they smoke together and flirt lightly. Before leaving, he kisses her, and Marisa feels a rare flicker of uncomplicated warmth.

She eats, rests, and prepares herself for the evening’s speeches.

A bombastic “divinity coach” delivers an over-the-top motivational talk filled with religious imagery and clichés, and her coworkers respond with earnest enthusiasm. On her way to get more wine, Marisa is told she is now the second speaker and has fifteen minutes to prepare.

She rushes to her room, throws together an absurd PowerPoint full of stolen internet content, and then makes a reckless decision: she empties an entire stash of MDMA into the pitchers of pineapple juice meant for the audience.

Her talk becomes a strange blend of humor, dance, loud music, and fake wisdom. The MDMA kicks in; her coworkers loosen, dance, hug, and laugh more freely than she has ever seen them.

The night turns chaotic but oddly affectionate. Even Maika dances with her.

For a brief time, Marisa feels part of a group rather than trapped inside her own alienation.

When overwhelmed, she slips outside and falls asleep under the stars, wrapped later in a shawl someone places over her. In the morning, she sees her reflection and thinks, surprisingly, that she looks good.

The day had been chaotic, frightening, and risky, yet something inside her feels lighter.

Back at the office, the consequences unfold. HR opens an investigation after a speaker ends up hospitalized with drugs in his system.

Mandatory tests are ordered. Department heads panic.

Maika writes in frantic all-caps emails. Throughout the chain, Marisa’s automated out-of-office reply keeps firing, cluttering the thread and irritating everyone.

No one acknowledges that she is responsible for the drug incident.

Time passes. One hot September morning, Marisa walks through Madrid, irritated by the heat and her cheap sandals.

At a busy intersection, her bag spills, and she crouches to gather her belongings. Lost in her thoughts, she doesn’t see the speeding food-delivery cyclist who crashes into her.

The collision triggers a chain reaction involving scattered pizzas, a smashed bike, and a car swerving over something “squishy,” which turns out to be her. The surrounding crowd freezes before emergency services arrive.

Even injured, Marisa laughs faintly upon hearing that the cyclist asked whether he could still deliver the pizzas.

At the hospital, doctors list her injuries: dislocated shoulder, broken ribs, cracked hip, broken wrist, extensive bruising, and the loss of three fingers on her right hand. Friends and family visit; Pablo and Elena remain constants.

Her parents stay several nights before exhaustion forces them home. Her boss visits with hollow sympathy.

When Marisa gestures to her bandaged hand and says she cannot return to work, he dodges the implication.

Over time, the pain eases, flowers wilt, and visits dwindle—except from Pablo and Elena. A doctor bluntly informs her she may face long-term or permanent disability.

When she jokes about playing the guitar again, he shakes his head.

Elena arrives one day with quality groceries and better pillows, explaining that a lawyer friend believes Marisa can claim substantial compensation from both the delivery company and the rider, as well as receive long-term disability benefits due to the accident occurring on her way to work. The sum might allow her to avoid returning to the agency entirely.

Marisa practices eating with her left hand while Elena encourages her. Pablo arrives with beer, and the three of them share a makeshift picnic.

Watching them, Marisa recognizes them as her chosen family. She imagines how she will live on in office legend as the woman who lost three fingers in a bizarre accident, her absence becoming mythologized without requiring her participation.

As she eats ripe tomatoes in her hospital bed, she grasps what truly matters: the quiet presence of people who care, the comfort of a good bed, the simple pleasure of food that tastes real, and the possibility of a life no longer dictated by the empty grind of work. In this moment, she understands she may finally be free to build a life that feels like her own.

Characters

Marisa

Marisa stands at the center of Discontent, an advertising creative whose inner world is defined by exhaustion, dread, and a constant oscillation between numbness and hyper-awareness. Her daily life is a performance she no longer believes in: the forced smiles on video calls, the inflated timelines, the empty “girlboss” posturing she slips into on good days when her anxiety briefly loosens its grip.

Her work in advertising has hollowed her out, teaching her to sell illusions while privately succumbing to the very insecurities those illusions exploit. She is cynical, self-mocking, and deeply perceptive—an observer who sees through corporate hypocrisy, patriarchal expectations, and performative feminism, yet feels unable to escape them.

Her coping strategies reveal the fracture lines in her psyche: compulsive YouTube binges, Ativan, weed, sarcastic comments on strangers’ videos, reckless decisions like drugging her coworkers, and impulsive intimacy with her neighbor. Marisa carries unresolved grief for Rita, whose death mirrors her own internal unraveling, and she fears becoming as invisible as the YouTuber Marina Joyce—noticed only by “true fans” while silently begging for help.

After her accident, stripped of her job’s demands and her body’s former ease, she allows herself to imagine a different kind of life, one defined not by productivity but by connection, pleasure, and slowness. She emerges not reborn but softened, discovering that survival sometimes begins with something as small as good tomatoes, a soft pillow, and people who love you.

Rita

Rita is both a ghost and a moral compass in the story—an absence with as much weight as any living character. Quiet, intelligent, and sharp-eyed, she shared Marisa’s skepticism about their industry and was one of the few colleagues who spoke to her with genuine curiosity and compassion.

She recognized Marisa’s panic attacks before Marisa herself did and urged her toward therapy, her attentiveness hinting at a depth of emotional sensitivity that ultimately made the office environment unbearable. Her suicide haunts the narrative not as a dramatic twist but as a quiet indictment of an industry and culture that valorizes burnout and punishes vulnerability.

Marisa stores Rita’s belongings in a sealed box like an emotional time capsule she is afraid to open—a symbol of guilt, fear, and the resemblance she sees between Rita’s collapse and her own trajectory. When she eventually confronts the box, what she finds is not a clear explanation but an intimate glimpse into Rita’s pain—a reminder that invisibility can be deadly.

Rita’s memory becomes a mirror in which Marisa measures her own fragility, a constant question about what could happen if she continues living the life she despises.

Natalia

Natalia is Marisa’s junior coworker—eager, hardworking, and still naïve enough to believe the corporate myth that passion and extra effort will be rewarded. She idolizes Marisa in a way that both flatters and troubles the older woman.

Marisa both exploits and protects her: assigning her the bulk of the work while also shielding her from scapegoating, giving her just enough praise to keep her afloat, and watching with a mix of affection and dread as Natalia mirrors the same early-career enthusiasm she once had. Natalia represents the younger version of Marisa—the version who still believed in the industry, who thought talent mattered, who hadn’t yet learned that advancement often comes from simply surviving long enough.

Her small crises, such as the panic over stolen coffee capsules, expose how deeply she internalizes corporate pressure. In Natalia, the reader sees both the cruelty of a system that thrives on youthful devotion and the inevitability of future burnout unless she escapes.

Ramón

Ramón, Marisa’s boss, is the face of corporate absurdity—charming, oblivious, and perpetually delegating real responsibility downward. He expects emotional labor from Marisa, positioning her as the office’s “feminist advisor” while ignoring the misogyny baked into the firm’s culture.

He is opportunistic yet oddly affectionate, offering forehead kisses at the hospital that blur the boundaries between paternalistic concern and workplace manipulation. Ramón fragments into contradictions: he is proud of Marisa when she saves a crisis, but indifferent to her well-being; he wants the team-building retreat to feel meaningful, yet is blind to the damage it causes; he calls the accident “a disaster,” but mostly because of the paperwork.

His presence highlights how institutions depend on people like him—leaders who maintain order while remaining insulated from emotional consequences.

Maika

Maika embodies ambition turned feral. Hypercompetitive, aggressive, and obsessed with control, she treats paintball like warfare and the office like a battlefield.

She weaponizes corporate language, thrives on scapegoating, and adopts the neoliberal model of empowerment that rewards cruelty as efficiency. Yet beneath her sharp edges lies a vulnerability revealed only briefly—such as when she softens after seeing Marisa’s panic attack or when she covers Marisa with her shawl after the drug-fueled retreat.

She is both antagonist and unexpected caretaker, a contradiction that reflects the book’s rejection of simple villains. Maika is a product of the system as much as its enforcer, simultaneously terrifying and strangely human.

Pablo

Pablo, Marisa’s neighbor and sometime lover, offers a kind of low-stakes intimacy—physical comfort with emotional ambiguity. Their relationship is grounded in convenience, fondness, and shared loneliness rather than commitment.

He drifts in and out of her life like a warm draft from an open door, offering beer, conversation, sex, and occasionally blunt honesty. Pablo represents a version of companionship that is imperfect but real, unburdened by the expectations of romance.

After Marisa’s accident, he shows up consistently—bringing beer to the hospital, joking gently, and integrating into her fragile support system. He becomes part of her “found family,” a reminder that love can take forms that the traditional script never accounts for.

Elena

Elena reappears in Marisa’s life like a spark—glamorous, self-invented, and unapologetically liberated from traditional work. She refuses to romanticize labor, treating femininity, beauty, and sexuality as strategic tools rather than moral virtues.

She is the mirror opposite of Marisa: where Marisa is exhausted by performance, Elena controls it with artistic precision. Their reunion awakens dormant desires in Marisa—desires for freedom, art, pleasure, and genuine connection.

Elena undresses her gently, removes her makeup tenderly, and confronts her with the possibility of a different life. After the accident, she becomes a fierce caretaker, bringing comfort items, high-quality food, and legal advice.

She is the friend who appears not only in crisis but in the aftermath, the one who pushes Marisa toward the idea that a life outside of corporate servitude might actually be possible.

Emilio

Emilio, the young paintball monitor, is a brief but meaningful presence. His calm, grounded manner during Marisa’s panic attack creates a rare moment of safety in a story dominated by anxiety.

He sees her clearly in a way no coworker does, naming her distress without judgment and offering practical comfort—orange juice, a pastry, a slow walk back to the hotel. Their kiss is tender rather than sexual, a fleeting connection driven by kindness rather than need.

Emilio symbolizes an alternative mode of masculinity: attentive, intuitive, and disinterested in power. His presence lingers as a reminder that care can come from unexpected places.

Themes

Corporate Alienation and the Performance of Professional Identity

In Discontent, corporate life functions not as a backdrop but as a suffocating ecosystem in which the protagonist’s daily existence is shaped, drained, and ultimately distorted. Her workplace is a polished machine powered by superficial interactions, manufactured enthusiasm, and unspoken competition, yet beneath that veneer lies a profound hollowness that she experiences as an almost physical pressure.

She does not consciously choose her professional persona; instead, it materializes through years of habitual self-betrayal—forced smiles in video calls, fabricated excitement during brainstorming sessions, strategic half-truths about deadlines, and a constant need to appear competent. This long-term performance erodes her sense of self, leaving only a shell that must be animated each morning for the benefit of colleagues who would barely recognize the person underneath.

The rituals of office life take on an absurdist quality: corporate condolences reduced to clichés, feminist rhetoric used as décor for managerial decisions, and team-building activities treated as spiritual renewal. Her growing belief that only “true fans” could perceive her internal cry for help underscores how invisible a person becomes when functioning inside an institution that prioritizes productivity over humanity.

What makes her alienation more cutting is that she understands the mechanics of the illusion—she is responsible for creating advertising narratives that manipulate consumer insecurities—yet she feels unable to step outside the system. Professional identity becomes an ongoing negotiation between survival and self-erasure, and the cost of maintaining the façade accumulates quietly until she barely remembers what it would mean to feel present in her own life.

Emotional Exhaustion, Anxiety, and the Search for Relief

Emotional depletion spreads through her days like a slow fog, shaping her behaviors and decisions with a weight she struggles to articulate even to herself. Anxiety is not an episodic event but a constant undercurrent that she manages with Ativan, avoidance, and distraction.

YouTube becomes both escape and anesthesia, offering the sense of companionship and stimulation she cannot find at work or through meaningful relationships. Her panic attacks appear without clear triggers, often in transitional moments when her mind briefly surfaces from routine, as if her body is the only one acknowledging the depth of her distress.

These episodes reveal how close she remains to psychological collapse despite outward competence. Relief comes in scattered, unreliable forms: shared cigarettes with Pablo, art at the Prado, long showers, drugs during the retreat, and late-night videos of people eating.

None of these resolve her exhaustion; they simply grant temporary suspension. Even her reckless decision to drug the entire team is less an act of rebellion than a desperate attempt to create one moment of collective release—an artificial eruption of joy that mirrors her own need to feel something other than dread.

After the accident, the exhaustion finally catches up to her body: broken bones, lost fingers, and forced isolation bring a strange clarity that emotional burnout alone could not produce. For the first time, she slows down, rests, and allows herself to be cared for, suggesting that the body’s collapse becomes the turning point her mind could never initiate on its own.

Exploitation, Ethical Ambiguity, and the Violence of Contemporary Work Culture

The novel exposes how modern labor environments normalize exploitation through subtle coercion, moral camouflage, and emotional manipulation. The protagonist is both victim and participant in these dynamics: she exploits Natalia’s eagerness for approval, siphons ideas from students without guilt, and performs feminist discourse only when it serves her professional interests.

Yet she is simultaneously exploited by managers who offload responsibility onto her under the guise of empowerment, and by a corporate culture that expects limitless flexibility while rewarding minimal authenticity. Ethical boundaries blur until they feel irrelevant; everyone is simply trying to survive.

The minute-of-silence for Rita exemplifies this hypocrisy: colleagues responsible for her isolation now publicly mourn her, turning her death into an empty ritual that allows the company to perform moral awareness without accountability. The retreat, framed as an opportunity for personal growth, instead becomes an arena for forced vulnerability, absurd motivational speeches, and physical danger.

Her decision to spike the drinks stems from an acute awareness that the system itself is already violating boundaries—she merely pushes its logic to an extreme. After the accident, corporate concern once again reveals itself as procedural rather than emotional; the company’s primary reaction is administrative, rooted in liability rather than compassion.

Through these moments, the book insists that workplace violence rarely appears as aggression; it arrives as indifference, as expectation, as the slow grinding down of individuality in service of institutional stability.

Loneliness, Connection, and the Need for Witnesses

Loneliness in the novel is pervasive, quietly shaping her interactions even when surrounded by people. She drifts through friendships, romantic entanglements, and family relationships without ever feeling fully seen.

Her terrace conversations with Pablo provide momentary comfort, but the connection remains intermittent, fragile, and defined more by habit than intimacy. Elena’s reappearance disrupts this emotional drought: their reunion awakens dormant tenderness, care, and mutual recognition that her corporate life has long denied her.

Elena offers a form of witnessing that validates her vulnerabilities rather than exploiting them, especially in the scenes where she removes Marisa’s makeup or restructures her hospital bed to make it livable. This contrasts sharply with the office environment, where she is reduced either to a function or to a stereotype.

The presence of found family—Elena, Pablo, and eventually the delivery boy Emilio in a brief but grounding encounter—shows that connection emerges in unexpected pockets, outside the structures that claim to provide community. Helping her recover, sharing simple food in a hospital room, and sitting beside her without demanding performance all demonstrate the power of companionship that does not require emotional labor.

These relationships give her a sense of belonging she has never felt in professional settings, and through them, she realizes that what she craves is not admiration but understanding. Her accident, while devastating, becomes the catalyst for recognizing that life’s value rests not in achievement or recognition but in people who remain present even when she is at her most vulnerable.

Mortality, Trauma, and the Reconfiguration of Self

Death shadows the narrative long before the accident. Rita’s suicide hangs over the protagonist as a reminder of what happens when internal suffering remains unseen, and she fears that she is moving along the same trajectory without acknowledging it.

Her intrusive thoughts, fantasies of disappearance, and fascination with her own potential breakdown reveal a mind acutely aware of its fragility. The accident forces this confrontation into reality: the loss of her fingers, the brutality of the collision, and the shock of surviving create a rupture in her identity.

She must reimagine herself physically, professionally, and emotionally. The trauma strips away the illusions she maintained—about returning to normal, about the necessity of her job, about her place within the corporate hierarchy.

For once, she cannot perform competence because her body refuses to. Paradoxically, this vulnerability becomes freeing.

She sees how quickly the office will mythologize her, using her story without requiring her presence, and recognizes that she no longer needs to participate in the cycle of endless striving. Through pain, she gains a clearer sense of what matters: comfort, companionship, and the possibility of a life that does not demand constant self-compromise.

Trauma does not enlighten her; it removes the distractions that once kept her trapped, allowing her to rebuild her sense of self around autonomy rather than expectation.

The Hunger for Meaning and the Possibility of Reinvention

Beneath the protagonist’s cynicism lies a persistent longing for meaning, even when she mocks the very idea of purpose. Her fascination with YouTube conspiracies, her visits to the Prado, her conversations about monotony with Pablo, and her recurring thoughts about Rita all hint at a desire to understand her place in the world.

She is deeply aware that life feels repetitive and empty, yet she keeps searching—for beauty, for humor, for escape, for connection. The spontaneous joy of dancing at the retreat, the adrenaline of the crisis cabinet, the intimacy with Elena, and the kindness of Emilio all serve as fleeting reminders that life can still surprise her.

After the accident, reinvention becomes not a fantasy but a practical necessity. She must learn to eat with her left hand, consider a future without returning to the agency, and imagine a life supported by disability benefits rather than professional advancement.

What emerges is not a grand revelation but a shift toward simplicity: the realization that she can build a life defined by comfort, companionship, and autonomy rather than performance. Reinvention, in her case, is not about dramatic transformation but about quietly stepping away from the structures that once dictated her identity.

Her final reflections show a woman beginning to construct a future grounded in small but meaningful pleasures, acknowledging at last that survival does not require constant striving, and fulfillment might be found in the understated moments she once overlooked.