Doll Parts by Penny Zang Summary, Characters and Themes

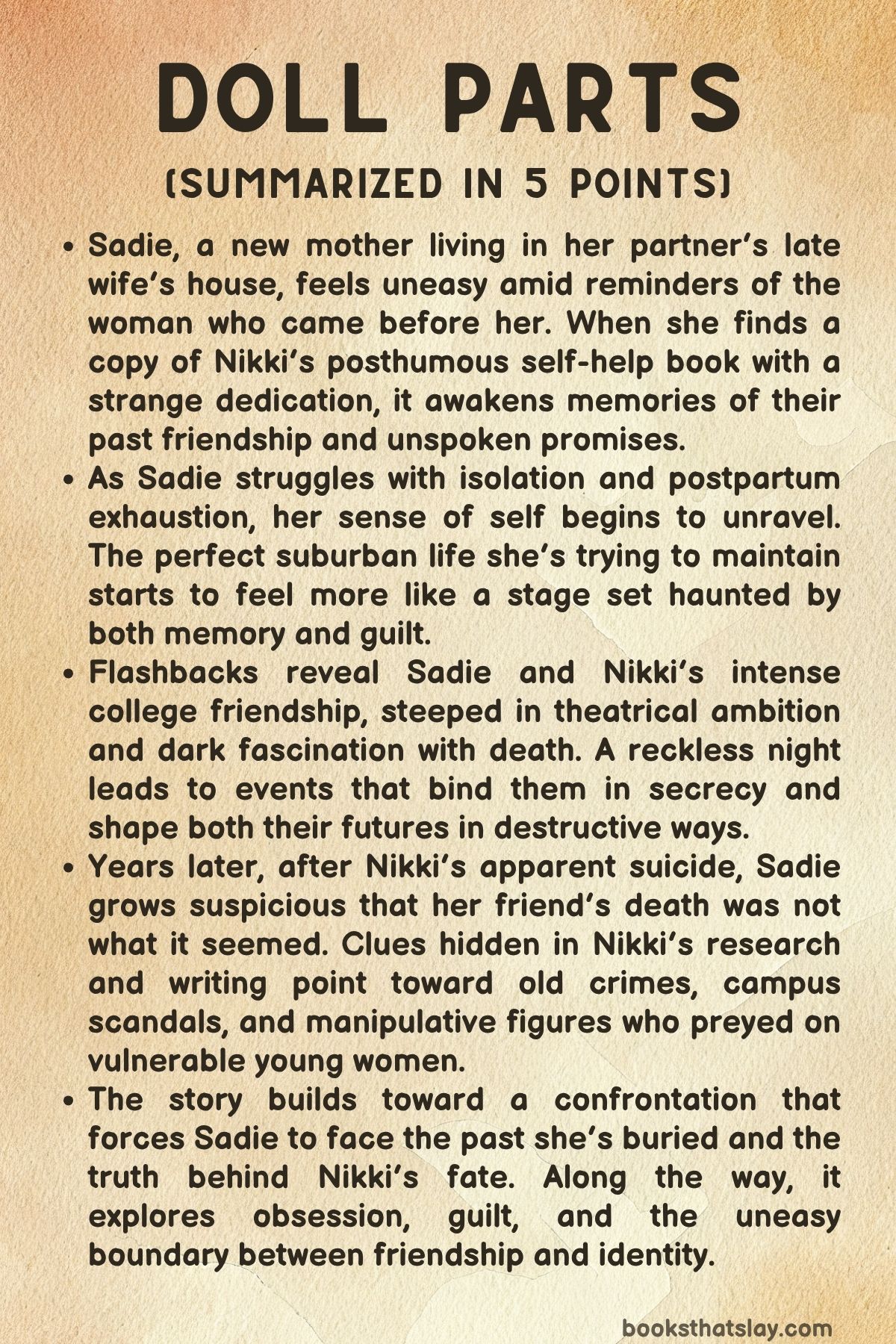

Doll Parts by Penny Zang is a dark psychological thriller that blurs the lines between memory, motherhood, and madness. It follows Sadie, a new mother haunted—literally and figuratively—by the ghost of her partner’s late wife, Nikki, a self-help author with a murky past.

When a mysterious book and old secrets begin resurfacing, Sadie is drawn into a spiral of paranoia, guilt, and obsession that unravels the truth about Nikki’s death and their shared history. Moving between past and present, the novel explores trauma, female friendship, and the sinister undercurrents hidden beneath suburban perfection.

Summary

Sadie lives in an immaculate suburban home with her partner, Harrison, and their baby, Rhiannon. The house, however, is not hers—it belonged to Harrison’s late wife, Nikki, a celebrated self-help author who supposedly took her own life.

Surrounded by Nikki’s untouched belongings and memories, Sadie feels like an intruder in another woman’s world. When a package arrives containing copies of Nikki’s new posthumous book, The Self-Care Cure, Sadie is unnerved to find a dedication reading, “To my bestie: I would never leave without you. I pinkie swear. ” The message reawakens memories of their intense college friendship, which ended almost two decades ago under mysterious circumstances.

In her isolated new-mother routine, Sadie struggles with exhaustion and anxiety. She performs domestic rituals—sterilizing bottles, managing chores, exercising—while suppressing her growing sense of unease.

Harrison treats her distress as simple “baby blues,” but Sadie’s unease deepens when she begins hearing strange noises through the baby monitor and seeing lights under the locked office door that once belonged to Nikki. The sense of haunting feels real—Nikki’s presence seems to linger, accusing and watchful.

The story shifts to the past, to Loch Raven College, where Nikki and Sadie first met as students. Nikki, grieving her mother’s suicide, was a quiet scholarship girl drawn to Sadie’s wild energy.

Together, they built a friendship that was all-consuming and strange—filled with secret jokes, Polaroids, and late-night confessions. They acted in a macabre student play, Night of the Living Dead: Miss World Edition, a gothic satire that mirrored their fascination with death and beauty.

Their campus, plagued by recurring suicides of young women known as the “Sylvia Club,” created a constant undercurrent of morbidity.

Nikki’s life at Loch Raven darkened under the influence of Professor Weedler, a predatory teacher obsessed with the deaths of women like Sylvia Plath. His inappropriate attention and morbid lectures trigger Nikki’s memories of her mother’s death.

Sadie, impulsive and protective, drags Nikki to a college party to cheer her up. There, they swap dresses—a small act that will later carry heavy meaning.

As the night spirals, Nikki drinks too much, hallucinates faces in mirrors, and loses her grip on reality. Sadie leaves with another student, promising to return, while Nikki’s night ends in trauma and confusion.

Years later, Nikki is dead, and Sadie reconnects with Harrison at the funeral. The body in the casket wears an orange dress—the same one Sadie had once worn the night everything went wrong.

Harrison tells her it was Nikki’s wish to be cremated in that dress. Sadie, convinced that Nikki would never take her own life, grows close to Harrison and eventually moves into Nikki’s home, taking her place as both partner and mother figure.

Yet the arrangement feels cursed. When Sadie begins receiving posthumous emails from Nikki’s pseudonym, Annie Minx, she interprets them as messages meant specifically for her.

The ghost of their shared past refuses to rest.

Haunted by guilt, Sadie begins to investigate Nikki’s death. She discovers Nikki’s hidden research on the “Sylvia Club”—the group of dead Loch Raven students—and the suspicious suicides that occurred across decades.

Her search leads her to locked drawers, missing notebooks, and encrypted files on Nikki’s computer. As she digs deeper, she encounters Lucille, a determined journalist investigating a cold case linked to Loch Raven.

Lucille suggests that Nikki was close to uncovering a long-buried scandal before her death. Sadie’s paranoia intensifies when she notices a navy-blue sedan following her through the neighborhood.

Inside is Lucille, who admits that new police files suggest Nikki may have been involved in a hit-and-run years earlier—the death of a professor named Weedler.

Flashbacks reveal the horrifying truth. One night, desperate to plead for her scholarship, Nikki went to Weedler’s home with Sadie.

Weedler tried to assault her, and Sadie intervened. Later, while driving away in panic, they hit someone on the road—Weedler himself.

Believing him dead, they rolled his body to the roadside and fled, terrified that no one would believe them. When the news broke that Weedler had been killed in a hit-and-run, the college erupted in scandal.

Nikki and Sadie swore secrecy, making a pinkie promise to protect each other forever.

Back in the present, Sadie’s mental state deteriorates. She hallucinates Nikki’s ghost appearing eyeless and accusatory, whispering, “You owe me.” She suspects Harrison knows more than he admits, and even begins to question her neighbor Bernie, who seems overly interested in Nikki’s life. Meanwhile, Lucille continues to push the investigation, linking Weedler’s death, Nikki’s supposed suicide, and a string of unexplained student deaths to one figure: Dr. Gallina, a Loch Raven professor who was once part of the original “Sylvia Club.

As Sadie follows the trail back to the college, she meets Caroline, Nikki’s daughter, who is also seeking answers. Caroline’s calm intelligence contrasts Sadie’s unraveling nerves, and together they begin piecing together Nikki’s hidden work.

They discover that Gallina not only encouraged suicidal ideation among students but may have manipulated their deaths for her own academic gain. Nikki, once her student, had begun investigating her before she died.

The story builds toward a violent confrontation at a memorial honoring “Annie Minx. ” During the ceremony, Caroline stages a mass performance by students dressed in black, turning the event into a public reckoning for Loch Raven’s history of silence.

Gallina, appearing to control the narrative, secretly possesses Nikki’s blue spiral notebook—evidence of everything. Sadie sees her holding it and rushes to the rooftop of Hope Hall, where Gallina, Caroline, and Lucille are already gathered.

In a chaotic struggle, Gallina admits that she manipulated young women into suicidal despair, claiming it was “a form of help. ” She also implies that Nikki’s death was not suicide but an “accident” engineered by others.

Sadie and Gallina fight; both fall through a glass skylight, but only Sadie survives.

Afterward, Gallina is arrested, wheelchair-bound, and publicly disgraced. Witnesses come forward confirming she pushed a student years ago.

Bernie disappears, likely complicit. Lucille’s reporting exposes the decades of abuse, while Caroline and Sadie form a fragile bond, caring for Rhiannon together.

They uncover Nikki’s final plan—her apparent suicide was staged as insurance against her killers, complete with coded messages and hidden assets meant to protect Sadie and her daughter.

In the end, Caroline reads a message Nikki left behind under her pen name, Annie Minx, assuring Sadie that she was never truly gone and that her life was meant to continue. Sadie, scarred but alive, accepts this truth.

She understands that Nikki orchestrated her survival, that their promise endures beyond death—not as haunting, but as inheritance. The story closes with Sadie holding her child, aware that the ghosts of the past still linger but no longer own her.

Characters

Sadie

Sadie is the emotional core of Doll Parts, a woman whose journey oscillates between guilt, obsession, and fragile resilience. Once a vivacious and reckless college student, she is now trapped in a cycle of domestic perfection and psychological decay.

Her life with Harrison, Nikki’s widower, symbolizes her attempt to reclaim a past she destroyed and to inhabit a role that was never truly hers. Motherhood intensifies her vulnerability; her postpartum state heightens every insecurity, every haunting echo of Nikki’s presence in the house they share.

Sadie’s unraveling manifests in hallucinations, paranoia, and a compulsive need to uncover the truth behind Nikki’s death. Yet beneath her instability lies a profound sense of loyalty—her fixation on Nikki is part guilt, part love, and part an identity crisis.

Sadie’s past with Nikki defines her entirely; the pinkie-swear they made to never leave each other becomes both a promise and a curse. As the narrative progresses, she transforms from a passive sufferer into an active seeker of truth, reclaiming fragments of herself through confrontation with the ghosts—both literal and psychological—that bind her to Nikki and Loch Raven.

Nikki

Nikki embodies the intersection of brilliance and fragility, a young woman scarred by inherited trauma and academic exploitation. Her mother’s suicide leaves her adrift in grief, and her scholarship status at Loch Raven College positions her as both privileged and preyed upon.

Her intellect and curiosity about “sad girls” like Sylvia Plath lead her into a morbid fascination that mirrors her own unraveling. As an author—first as a student researcher and later as Annie Minx—she channels her pain into a voice of empowerment, yet her self-help persona is riddled with irony: she cannot heal herself.

Nikki’s relationships, especially with Sadie, blur the lines between friendship, obsession, and symbiosis. Their bond is simultaneously nurturing and toxic, with Nikki alternating between dependence and control.

In death, she becomes a spectral figure, her posthumous messages and lingering presence forcing others to reckon with buried truths. Nikki’s tragedy is not just her demise but her transformation into an idea—one that others consume, misinterpret, and immortalize without ever understanding the living woman behind it.

Harrison

Harrison represents control, order, and repression in a world of chaos. As Nikki’s widower and Sadie’s partner, he embodies the unsettling continuity between the two women’s lives.

His calm demeanor masks emotional detachment and a quiet authoritarianism; he dictates Sadie’s routines, minimizes her distress as “baby blues,” and keeps the house as a mausoleum for his first wife. Through him, Doll Parts examines male complicity in women’s suffering—how a man’s insistence on normalcy can smother the instability festering beneath.

Yet Harrison is not purely villainous; he is a man bound by guilt and self-deception, seeking comfort in routine. His relationship with Sadie, echoing his past with Nikki, suggests his inability to engage authentically with women as equals.

Instead, he becomes the keeper of their ghosts, maintaining appearances while denying their pain.

Professor Weedler

Professor Weedler is the novel’s embodiment of academic predation and the corruption of intellectual power. Charismatic yet sinister, he exploits his authority over vulnerable students like Nikki, fetishizing their trauma under the guise of scholarship.

His lectures on Sylvia Plath and other “tragic women” reveal an eroticized fascination with female suffering. Weedler’s manipulation of Nikki—his unwanted advances, condescension, and exploitation—exposes the institutional rot of Loch Raven College, where young women’s pain becomes academic currency.

His death, struck by a car in an ambiguous accident involving Nikki and Sadie, becomes the moral and narrative fulcrum of the novel, linking guilt, secrecy, and the legacy of violence that permeates the women’s lives. Even in death, Weedler’s influence lingers, shaping both the Sylvia Club’s mythology and Nikki’s lifelong fixation on uncovering the truth about systemic predation.

Dr. Gallina

Dr. Gallina is a chilling figure who bridges mentorship and manipulation.

At first appearing as a caring faculty member, she gradually reveals herself as a puppet master orchestrating the fates of “sad girls” through calculated psychological grooming. Her history at Loch Raven spans decades, with her presence threading through every generation of suicide and despair.

Gallina’s philosophy—that despair can be transformed into choice—becomes a perverse justification for her role in pushing young women toward self-destruction. She exploits grief under the guise of guidance, masking predatory curiosity with intellectualism.

In her final confrontation with Sadie, Gallina’s narcissism and god-complex fully emerge. She perceives herself as an architect of transformation, incapable of remorse.

Her downfall exposes the generational cycle of exploitation that both Nikki and Sadie inherit and resist.

Caroline

Caroline, Nikki’s daughter, represents renewal and the reclamation of agency. Growing up in the shadow of her mother’s myth and her father’s emotional distance, she becomes a bridge between past and present.

Caroline’s discovery of her mother’s secrets and her eventual alliance with Sadie mark her as a moral compass in a story dominated by deceit. She inherits Nikki’s intelligence and courage but refuses to be consumed by the same self-destructive impulses.

Her act of publicly reading Nikki’s final message underlines her strength as both witness and survivor. Through Caroline, the novel closes the loop of maternal trauma—transforming inherited despair into truth-telling and resistance.

Bernie

Bernie begins as a seemingly harmless, humorous neighbor—a grounding presence for Sadie in her chaotic suburban life. Yet as the narrative unfolds, her role darkens.

Beneath her folksy demeanor lies complicity; as Gallina’s mother and an informant, she becomes the connective tissue between the suburban domestic sphere and the academic world’s corruption. Bernie’s betrayal is subtle and psychological—she spies, manipulates, and ultimately aids Gallina’s schemes.

Her duality underscores Doll Parts’ central theme: that evil often hides within the ordinary, that the comforting neighbor or mentor may be the very source of rot. Bernie’s disappearance at the end feels like an extension of her parasitic nature—she feeds on others’ pain and vanishes when the truth surfaces.

Diana Noble

Diana functions as a social mirror, reflecting the world’s obsession with curated perfection. As a neighbor entwined in Nikki’s past and a participant in Sadie’s unraveling, she represents both complicity and conscience.

Her initial avoidance of Sadie suggests guilt or fear, but later she emerges as an unlikely ally, helping with Rhi and participating in the confrontation with Gallina. Diana embodies the modern, performative woman—social-media driven, self-aware yet self-deceptive—whose empathy flickers through layers of irony.

Through her, the novel critiques the performative culture of wellness and the façade of support among women conditioned to compete rather than connect.

Lucille

Lucille is the investigative voice of the narrative, a reporter who refuses to let history stay buried. Her relentless pursuit of the truth about Weedler’s death and Nikki’s past forces the story’s hidden layers to surface.

Lucille operates in the moral gray zone—motivated by ambition but also genuine conviction. Her confrontations with Sadie and Gallina push the plot toward revelation.

She symbolizes the voice of accountability, the external force that challenges the cyclical silence surrounding women’s suffering. In the end, Lucille’s presence ensures that the story of Loch Raven and its ghosts is not erased again.

Rhiannon

Rhiannon, though an infant, symbolizes innocence and the fragile continuity of life. She is the quiet center around which Sadie’s chaos spins, representing both hope and burden.

To Sadie, Rhiannon is a mirror—her cries echo Sadie’s suppressed fears, her dependence amplifies Sadie’s own helplessness. The baby’s presence grounds the supernatural and psychological elements of the story, reminding readers that amidst all the ghosts, there is still a future to protect.

Rhiannon’s survival, ultimately in Diana’s care, stands as a testament to resilience and renewal, closing the novel’s cycle of trauma with the faintest promise of peace.

Themes

Identity and Inheritance of the Self

The story in Doll Parts explores identity as something unstable, layered, and often inherited through the ghosts of others rather than discovered within oneself. Sadie’s sense of self is fragmented between her present role as a mother, her past as Nikki’s best friend, and her uncomfortable position as the new wife inhabiting the dead woman’s home.

The walls, the furniture, even the air of the house feel borrowed, leaving Sadie to question whether she is living her own life or performing someone else’s unfinished script. The presence of Nikki’s possessions—her lipstick, her robe, her locked office—becomes a literalization of this possession of identity.

Sadie’s every action echoes a ghost’s memory, and her struggle to define herself apart from Nikki mirrors the broader idea of how women’s identities are shaped by societal roles, expectations, and the lingering influence of others. Nikki, too, was defined by others—her professors, her readers, her husband—each turning her trauma into something consumable.

The posthumous publication of her book under a pseudonym reinforces this idea: even in death, her name and image are curated for others’ comfort. The novel portrays identity as something that cannot remain intact when built on the silence, guilt, and borrowed dreams of others.

Through the parallel lives of Sadie and Nikki, Penny Zang constructs a haunting examination of how identity can become both an inheritance and a burden, leaving women to inhabit spaces—both literal and emotional—designed by those who came before them.

Female Friendship and Obsession

At the heart of Doll Parts lies a friendship that transcends ordinary intimacy, becoming a consuming force that defines both women’s lives. Sadie and Nikki’s bond begins in youth, filled with creative energy and shared vulnerability, but it quickly takes on darker undertones of dependency and control.

Their pinkie-swear—“I would never leave without you”—serves as both a promise and a curse, binding them long after physical separation and even death. The novel depicts how female friendship, often idealized in popular culture as nurturing and supportive, can also harbor jealousy, rivalry, and unhealthy attachment.

Sadie’s later life becomes a replay of her connection to Nikki, suggesting she never escaped its emotional gravity. Her relationship with Harrison, Nikki’s widower, becomes another extension of that obsession—Sadie literally steps into Nikki’s life, taking her place as wife and mother, as though possession could substitute for reconciliation.

The friendship’s intensity, laced with guilt and unresolved trauma, echoes the theme of doubleness: Sadie and Nikki are mirrors of each other, each reflecting what the other cannot face alone. Their relationship critiques the myth of the singular self, showing instead how identities blur within intimacy, especially when love and envy intertwine.

The haunting that drives Sadie is not just supernatural; it is emotional residue from a friendship that never allowed either woman to exist independently.

Motherhood and the Performance of Perfection

Motherhood in Doll Parts is portrayed as a performance that isolates rather than fulfills. Sadie’s routines—sterilizing bottles, tracking caffeine, adhering to schedules—create an illusion of control, but beneath this surface lies anxiety, guilt, and profound loneliness.

Her postpartum experience exposes the societal pressure to embody “the good mother,” a role marked by self-denial and constant vigilance. The suburban setting of Hidden Harbor amplifies this expectation, where other mothers appear flawless, curated for social media and public perception.

Sadie’s inability to meet those invisible standards drives her deeper into self-doubt, as every deviation—her exhaustion, her unease, her inability to “bounce back”—is treated as pathology. The novel critiques the commodification of wellness and self-care, epitomized by Nikki’s career as a self-help author.

Nikki’s book, The Self-Care Cure, becomes an ironic emblem of this contradiction: a woman’s marketed advice about healing masks her private despair and eventual death. Through Sadie’s experience, Penny Zang reveals how modern motherhood, especially under capitalist and patriarchal scrutiny, becomes an impossible balance between nurturing others and erasing oneself.

The performance consumes Sadie until her individuality blurs, reinforcing that the myth of the perfect mother is both unattainable and destructive, a script written to suppress rather than celebrate maternal complexity.

Guilt, Trauma, and the Haunting of Memory

The haunting in Doll Parts operates as both a psychological and moral phenomenon. Sadie is haunted not only by Nikki’s literal ghost but also by the unresolved guilt of their shared past—the accident that may have caused Weedler’s death and the lies that followed.

The supernatural elements of flickering lights, laughter through baby monitors, and eerie dedications in books serve as manifestations of Sadie’s conscience, externalizing the trauma she cannot face directly. Guilt becomes a living entity that infiltrates her domestic life, linking motherhood with the act of caretaking for ghosts.

The more she represses her past, the more it asserts itself through hallucination and paranoia. For Nikki, trauma was the inheritance of her mother’s suicide, a wound that shaped her relationships and her writing.

The repetition of suicides at Loch Raven College—embodied by “The Sylvia Club”—underscores how trauma replicates itself across generations and institutions, especially for women whose pain is aestheticized rather than treated. Zang uses haunting as a metaphor for unacknowledged suffering, where the dead demand not vengeance but recognition.

The novel refuses easy closure; guilt is not absolved through confession but lingers as part of the living, suggesting that survival itself carries the burden of remembrance.

Power, Exploitation, and the Violence of Institutions

Throughout Doll Parts, the academic and domestic spheres function as twin systems of control over women’s bodies and stories. Loch Raven College, with its predatory professors and complicit administrators, becomes a breeding ground for exploitation disguised as mentorship.

Professor Weedler’s obsession with “dead women” like Sylvia Plath literalizes how institutions eroticize female suffering, turning it into intellectual spectacle. His manipulation of Nikki, under the guise of academic authority, exposes the coercive structures that punish vulnerability and reward silence.

Dr. Gallina’s later revelation as both mentor and predator extends this critique, showing how even women within power structures can perpetuate harm.

The “Sylvia Club,” an informal network of dead female students, becomes a grim archive of institutional neglect. In the domestic sphere, similar dynamics persist: Sadie’s dependence on Harrison mirrors the college’s power imbalance, as he infantilizes her grief and dismisses her intuition as hormonal instability.

The novel ultimately portrays institutions—universities, marriages, motherhood itself—as systems that consume women’s emotional and creative labor while erasing their autonomy. Zang’s portrayal of these settings reveals how exploitation often masquerades as care, how control hides behind the façade of guidance, and how the cycle of violence endures through the normalization of silence and compliance.

Death, Performance, and the Construction of Legacy

Death in Doll Parts is not an end but a continuation of performance. Nikki’s suicide—or possible murder—is choreographed like a scene, complete with costume, script, and stage.

Her posthumous presence, through books, emails, and apparitions, becomes another act in the theater of her life. Sadie’s attempts to reconstruct Nikki’s story transform her into both detective and performer, reenacting the same roles that Nikki once inhabited.

The recurring motifs of theater, masks, and costumes reflect how both women navigate identity through performance, even when authenticity is impossible. The novel questions what remains of a person after death: is it the curated image left behind, the stories told by others, or the lingering influence on those who survive?

Nikki’s transformation into “Annie Minx,” a brand of empowerment masking despair, exposes how death can be commodified, how legacy becomes another form of control. Sadie’s final reconciliation with Nikki’s memory is not about uncovering truth but accepting ambiguity—understanding that both life and death are stages where meaning is constructed rather than found.

In this way, the novel transforms death into an artistic act, one that mirrors the living world’s obsession with appearances, leaving readers to question how much of what survives is truth and how much is performance.