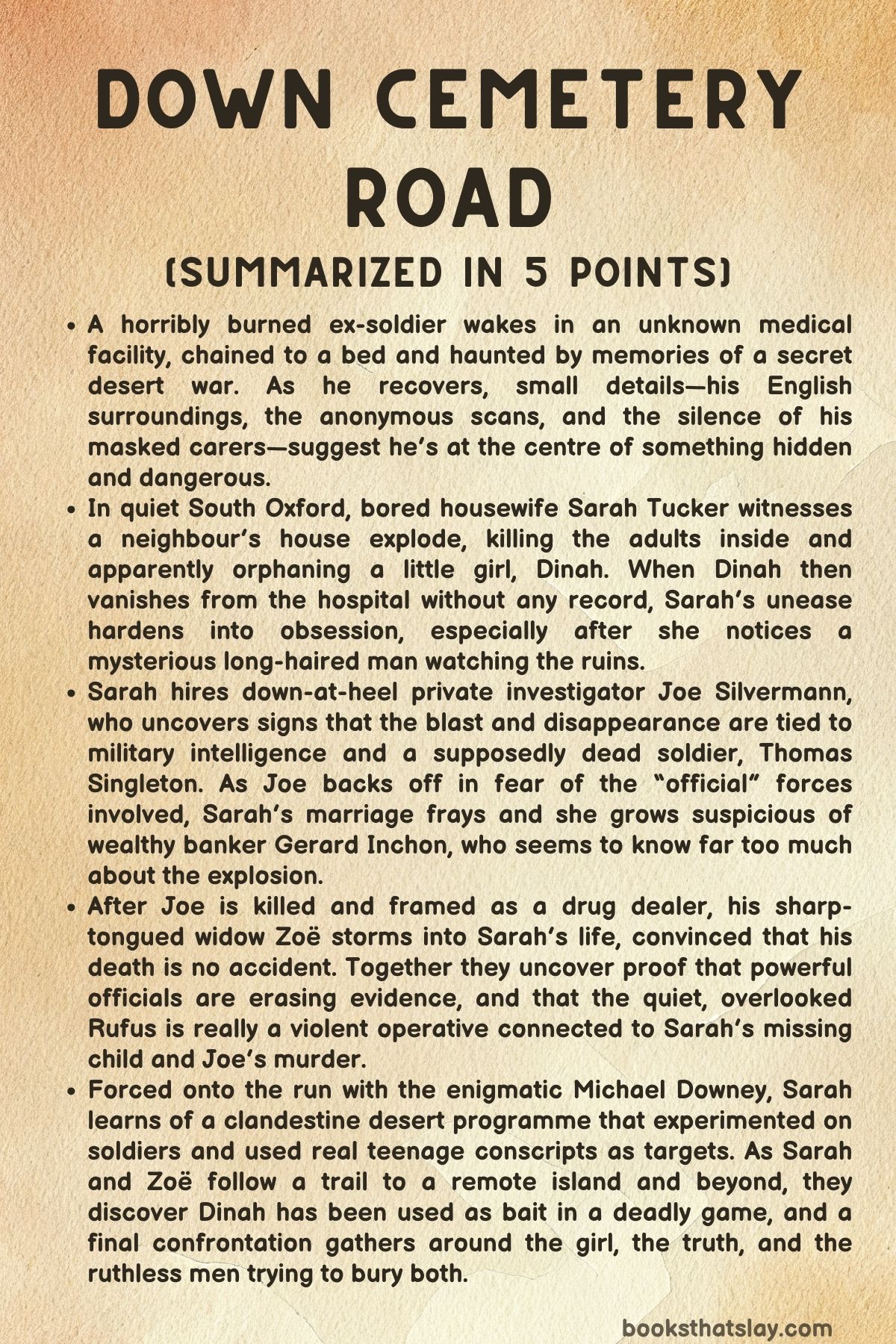

Down Cemetery Road Summary, Characters and Themes

Down Cemetery Road by Mick Herron is a darkly funny, quietly furious thriller about ordinary people stumbling into the machinery of the secret state. Set in Oxford’s terraces and rainy lanes rather than glamorous spy capitals, it follows Sarah Tucker, a bored woman with a stale marriage, who becomes fixated on a missing child after a house on her street explodes.

What starts as neighbourly concern turns into a hunt for the truth about a vanished girl, a dead soldier who will not stay dead, and a botched covert operation that powerful people are desperate to erase.

Summary

Down Cemetery Road opens with a burned man strapped to a hospital bed, convinced he is a prisoner in some foreign facility. In agony, he relives memories of a desert battlefield where teenage Iraqi conscripts are slaughtered from the air.

Masked staff with matching olive skin and hazel eyes tend to him with chilling detachment. When he finally manages to glimpse out of a window, he realises he is not in the Middle East at all, but in England.

The war he remembers and the life he has now been assigned clearly do not match.

The story switches to South Oxford, where Sarah Tucker is hosting a dinner party with her banker husband, Mark. Their guests include aggressive businessman Gerard Inchon, his polished wife Paula, and Sarah’s chaotic friend Wigwam with her quiet partner Rufus.

Over dinner, Gerard mocks Sarah’s stalled career and labels her a bored housewife, while they talk about war, profit and morality. The argument is cut short when a neighbouring riverside house explodes, partly collapsing into the water.

Shocked, they watch emergency services respond, but no one can do anything useful.

The ruined house belonged to Maddie Singleton. She has been killed, but her small daughter, Dinah, has miraculously survived, apparently protected by a wardrobe.

Another body, a man, is found in the wreckage. Sarah becomes obsessed with the child, especially after learning that Dinah’s soldier father, Thomas Singleton, supposedly died years earlier in a helicopter crash.

Troubled and restless, Sarah feels her own empty life reflected in the fate of this unwanted catastrophe and cannot shake the sense that something about the blast is being hushed up.

When Sarah visits the hospital to check on Dinah, a hostile administrator refuses to help and eventually claims the girl is “no longer in the hospital,” offering no explanation. Outside, a long-haired man with a military manner, Michael Downey, questions Sarah about the Singletons and then walks away.

The police dismiss her concerns. Convinced the authorities are hiding something, Sarah hires private investigator Joseph Silvermann, a clever but down-at-heel Jewish ex-Oxford student.

Joe discovers that Dinah’s hospital records mysteriously stop after admission, and that the dead man in the house is Thomas Singleton himself, officially already dead once.

Joe’s police contact panics after sharing this, warning of an information clampdown. Joe realises the blast is tied to national security and refuses to continue, fearing the consequences of crossing military intelligence.

He believes Dinah is being held somewhere safe but inaccessible. Before he walks away, he shows Sarah an old photograph of Singleton with another soldier: Michael Downey, the man she met outside the hospital.

Now Sarah knows the bearded watcher is connected to the girl, the explosion and the army.

Meanwhile, in London, senior officials try to contain the fallout from the Singleton operation. Amos Crane, a cold, analytical controller, and his violent brother Axel, a field agent, are mired in the mess created by the bombing.

Their superior Howard must reassure his own boss that nothing will leak. The dead man Downey had been tasked to help silence, the surviving child, and now a nosy woman in Oxford all represent loose ends that have to be tied off.

Sarah’s private life frays further. A drunken weekend at Gerard Inchon’s country cottage deepens her suspicion of him; he seems to know more than he should about the explosion and enjoys hinting that danger is coming her way.

Back in Oxford, Joe is abruptly killed and framed as a drug dealer. Under pressure, Sarah signs a police statement that supports the frame-up, then sinks into a haze of prescribed tranquilizers, her sense of reality eroding.

Joe’s widow, Zoë Boehm, storms into Sarah’s house, furious about the lies told about her husband. She is sharp, angry and unwilling to be pushed aside.

Convinced Joe was murdered and the drugs planted, she forces Sarah to walk through everything that has happened. Zoë has also seen Michael Downey watching the house.

Shamed, Sarah retracts her statement to the police, despite threats. A misdirected letter from Joe reaches her posthumously, confirming that Singleton has been reported dead twice and pointing her toward the Ministry of Defence.

Danger arrives in the shape of Rufus, Wigwam’s mild partner, who turns out to be Axel Crane under another name. He mocks Sarah, admits to killing Joe and hints he has disposed of Wigwam.

He locks the door, fashions a garrote from dental floss and attacks her. Sarah barely survives by triggering Joe’s personal alarm in his face, disorienting him.

As Axel moves in to finish the job, Michael Downey bursts through the door and shoots him dead. Shortly afterwards, Amos Crane and Howard view the aftermath; Amos decides to brand his own brother a terrorist and vows to hunt down Downey.

Downey smuggles Sarah out through Oxford’s streets, discarding his gun in drains and using multiple rail tickets to create false trails. On a station platform, Sarah quietly witnesses Mark kissing another woman, confirming that her marriage is hollow.

Downey leads her to a hotel in Malvern, where he finally explains his past. He and Singleton were part of a secret training unit in the desert, repeatedly sprayed with an unknown agent and officially recorded as dead.

Sent one day to capture “hostiles,” they instead found frightened teenage Iraqi conscripts being used as live targets. Stranded between duty, conscience and betrayal by their own side, they understood they would never be allowed normal lives.

Later, convinced that Downey is still alive and that Dinah is being held offshore as bait, Sarah teams up with Zoë. They hire a boatman, Jed, to reach a barren island with a single stone farmhouse.

Inside, they find two apparent corpses and, below ground, a dying woman in a child’s decorated room, Dinah’s teddy bear beside her. Government fixer Howard appears, coolly confirms that Dinah has been used to draw Downey out, and lets the women leave, believing he can track the bear’s hidden device.

The island “corpses” turn out to be playing dead for him; Downey has already rescued Dinah and left. Howard follows the teddy’s signal across country.

At the same time, Amos murders a pharmaceutical salesman named David Keller and takes his car and identity, picking up Sarah and Zoë by the roadside under the guise of helping stranded travellers. Sarah remembers a woodland chapel Downey once described and has “David” drive them there, not realising she is being delivered straight into Amos’s hands.

In the tiny stone church, they find Downey weak and ill, clutching Dinah and a gun. There is a brief reunion before Amos returns, revealed as the same man who first brought the teddy to Dinah.

He disarms them and toys with Zoë, showing off his skill with firearms. Zoë uses Joe’s advice about keeping the chamber under the hammer empty to make him misjudge a pistol, then seizes a moment and shoots him dead with Downey’s gun.

Amos’s personal crusade ends on the chapel floor.

Outside, Howard reaches the woods, tracking the teddy. Sarah, trying to get Dinah away in Downey’s old car, finds the keys missing and instead retrieves a shotgun from the boot.

Howard approaches, wounded from a fall but still armed, and offers Sarah a choice between silence and slaughter, hinting that everyone she cares about can be erased. When she drops the shotgun, he reveals he never intended any deal and fires at her.

The sabotaged shells explode in the barrel, destroying his arm instead. Sarah, shaken, still tries to save his life with a tourniquet before discarding the remaining ammunition.

She runs back through the trees to the chapel, lifts Dinah from the car and promises that things will be all right, though she has no guarantees. Zoë emerges alive from the church, lighter in hand.

With Amos dead, Howard maimed and exposed, and Dinah finally out of state control, Sarah, Zoë and the child stand at the edge of the woods facing an uncertain future. The conspiracy has been broken open, but the cost in lives, trust and innocence is far from small.

Characters

Sarah Tucker

Sarah Tucker begins Down Cemetery Road as a restless, self-diagnosed “bored housewife,” trapped between an underused intellect and a hollow marriage. At the dinner party with Gerard Inchon, she is belittled for her failed publishing job and mocked for her supposed Bored Housewife Syndrome, and that humiliation crystallizes something already simmering: a deep dissatisfaction with being reduced to a decorative spouse.

The explosion at the Singletons’ house gives that vague frustration a moral focus. Her fixation on Dinah is not simply maternal projection, although her own stalled conversations with Mark about having a child sharpen the resonance; it is also a refusal to accept the official narrative when something feels wrong.

The more institutions stonewall her—the hospital administrator, the police, the evasive bureaucracy—the more her stubbornness, curiosity and anger harden into a kind of improvised heroism. Sarah spends much of the book drugged, gaslit, intimidated and literally strangled, yet each time she claws back agency, whether by hiring Joe, standing up to Inspector Ruskin, retracting her coerced statement, or ultimately facing Howard in the woods.

She is not a trained operative or a brilliant strategist, but she is doggedly moral, and the climax shows her transformation from an insecure, self-doubting woman into someone capable of recognising a bluff, letting a man shoot himself with a sabotaged weapon, and still having enough humanity left to tourniquet his arm. Her final act of taking Dinah into her arms and walking toward Zoë is the culmination of that arc: she has chosen, against all pressure, to side with the vulnerable rather than with the powerful, even though she knows the cost will be the shattering of her old life.

Michael Downey

Michael Downey is introduced through glimpses: the long-haired, watchful man by the river, the stranger in the hospital car park, the offstage name in an old newspaper cutting. As his history unfolds, he emerges as the novel’s most haunted figure, a soldier damaged not only by combat but by his own side’s experiments.

In the desert training programme, he and Thomas Singleton are sprayed with unknown substances, used as expendable assets, and written off as dead in official records. The boy soldiers in his recurring memories are not enemies but terrified conscripts, turned into live targets for an exercise that masquerades as counter-terrorism.

Downey’s trauma is as much moral as physical: he has participated in something unforgivable, then discovered that he and Singleton are now liabilities to be erased. This knowledge drives him off the grid and sets up his obsession with protecting Dinah, whom he treats as his own child even though she is biologically Singleton’s.

He oscillates between ruthless competence and a kind of weary fatalism. He kills Ruthless/Rufus without hesitation, discards weapons methodically, leaves false ticket trails, and keeps moving because he understands exactly how his pursuers think.

At the same time, he is terminally ill from whatever he inhaled in the desert and fully aware that he is on borrowed time. That gives his actions a sacrificial edge: rescuing Dinah from the island, keeping her safe, and trusting Sarah and Zoë at the chapel become his way of salvaging a fragment of decency from a life deformed by state violence.

The burnt, restrained man who dreams of melting soldiers in the opening scene echoes Downey’s condition and mental landscape, positioning him as the embodiment of the book’s central horror: what happens when a government treats its own soldiers as disposable test subjects.

Zoë Boehm

Zoë Boehm strides into the story abrasive, furious and uncompromising, but that hard shell is built over fresh grief. She has just lost Joe, her ex-husband and still-beloved mess of a man, and her first move is to confront Sarah for having “got Joe killed” and for lying about his supposed drug dealing.

Zoë’s anger has multiple targets: the police who framed Joe, the invisible people who ordered his death, and Sarah herself as the civilian who, in Zoë’s eyes, stumbled into a world she did not understand. Yet Zoë does not retreat into bitterness; instead she picks up Joe’s unfinished trail.

That choice shows her stubborn loyalty and her refusal to let Joe’s memory be rewritten as that of a corrupt loser. Over the course of the book she becomes Sarah’s uneasy ally and, eventually, genuine partner.

On the island, she forces herself to go down into the basement despite her horror, because she knows that if she does not, no one will. She is practical where Sarah is impulsive, always calculating leverage—Jed’s cheque, the knowledge they can take to the press, the fact that they are more useful alive than dead.

Her competence culminates in the chapel confrontation with Amos Crane: she remembers Joe’s gun-safety advice about keeping the chamber under the hammer empty, uses that to draw out Amos’s arrogance, and then kills him with Michael’s gun when he overplays his hand. The scene fuses Joe’s legacy, Zoë’s quick thinking, and her willingness to shoot to protect others.

By the end, Zoë has become a kind of dark mirror to Sarah: where Sarah’s courage is rooted in sudden moral awakening, Zoë’s is tempered by long familiarity with danger and loss, and the two together form a fragile, improvised resistance cell against a state that assumes women like them can be bullied into silence.

Joseph Silvermann (Joe)

Joseph Silvermann begins as a faintly comic figure: the Oxford-educated private investigator in a shabby office, more excited to talk about theatre than about fees, half-flirting, half-showing off. His professional world is mundane—cheating spouses, missing kids of the ordinary kind, routine checks—and his main flaw is an inability to take things as seriously as he should.

Yet when Sarah hires him to look into Dinah’s disappearance, Joe proves more capable than his persona suggests. He works his contacts in the hospital, interprets the missing paper trail correctly as a sign of high-level interference, and follows his nose to the truth about Thomas Singleton’s official double-death.

His decision to get out once he realises the matter has shifted into national security territory is, ironically, a wise one, but the system will not permit even partial knowledge to linger. Joe is murdered and framed as a drug dealer, his file on Sarah deleted, his reputation dirtied to make any questions about his death seem like sentimental delusion.

From beyond the grave, however, he still shapes the narrative: his letter to the Ministry, his note to Sarah about Singleton, and the rape alarm she uses to fight off Rufus all carry fragments of him forward. In a story about how easily institutions make people disappear, Joe stands for the ordinary, flawed person ground up in the machinery; his death is a warning, but also the spark that hardens both Sarah and Zoë into the more resolute versions of themselves.

Amos Crane

Amos Crane is the cool, cerebral face of state violence. He works in darkness, literally and figuratively, surrounded by screens and data that he insists are only clues, never the whole story.

He sees himself as a professional controller, someone who uses ruthlessness efficiently rather than flamboyantly, in contrast to his brother Axel’s recklessness. For Amos, people are variables in a problem set rather than humans; Downey is a dangerous anomaly, Dinah is bait, Deedee and the island crew are assets to be manipulated, and even his own subordinates are instruments to be deployed or discarded.

Yet beneath the detached intelligence lies something more personal and unhinged, revealed when Axel is killed. Amos’s pursuit of Downey becomes not just an operational necessity but a vendetta, a mission to avenge his brother regardless of collateral damage.

His charm when talking to superiors and his calm during damage-control operations mask a deep-seated belief that he and men like him are the guardians of a democracy that must never admit how it is really protected. This self-justifying narrative allows him to rationalise atrocities and to plan the neutralisation of inconvenient witnesses like Sarah and Zoë as if he were simply tidying up files.

His death in the chapel, shot by Zoë after he briefly toys with her, is narratively satisfying because it punctures that sense of invincibility: the man who treats everyone else as expendable misjudges one “civilian” woman and pays the price instantly.

Axel Crane / Rufus

Axel Crane, known for most of the book by the innocuous name Rufus, is a study in hidden monstrosity. On the surface he appears as Wigwam’s quiet, somewhat mild-mannered partner, the sort of man who barely speaks at dinner parties and fades into the background while louder personalities like Gerard dominate the conversation.

This camouflage makes the revelation more chilling when he shows up at Sarah’s back door and drops the mask. The taciturn husband morphs into a sadistic killer who mocks Sarah’s trauma, sneers crudely about Joe’s death, and relishes revealing that he has likely murdered Wigwam as well.

His almost playful use of a garrote fashioned from dental floss, the way he locks the door and drops the key into a tea cup like a magician’s flourish, all emphasise a cold delight in control and suffering. As Axel Crane, he is the reckless field operative whose decisions—like using a bomb in a civilian terrace—trigger the entire crisis.

He is the man whose methods Howard has to “clean up” and whose excesses Amos both exploits and tries to manage. That such a figure lives for years as a barely noticed presence in Sarah’s social circle underscores one of the book’s nastier suggestions: that agents of state brutality can hide in plain sight, passing as gentle spouses and dinner guests until the moment they are activated.

Howard

Howard is the world-weary middle manager of the secret state, a man whose job is to clean up the mess left by cowboys like Axel but who is himself deeply compromised. Introduced being berated by his superior “C” over the Singleton explosion, he resents both the recklessness of the field and the hypocrisy of those above him.

Yet he is no whistleblower; he is a fixer. He is the one who arranges information clampdowns, who sends teams to manage the island where Dinah is held, who treats Deedee’s life as a piece of theatre in a staged scene designed to manipulate Downey.

On the island, his briefcase and bland exterior contrast sharply with the violence around him, but his lack of reaction to a dying woman shows how hollow his empathy has become. In the woods outside the chapel he tries to recast himself as the reasonable voice of the system, offering Sarah a choice between cooperation and catastrophe, claiming that secrecy protects democracy and that he personally was not responsible for the desert atrocity.

The moment Sarah drops the gun, he discards the pretence of negotiation and reveals that the deal was a lie, aiming the sabotaged shotgun at her as if it were simply another tool. The weapon’s explosion, destroying his arm, is a grimly literal payback: the apparatus of covert force maims one of its own enforcers.

Sarah’s instinctive effort to save his life afterwards complicates him further; he is not a cartoon villain but a hollowed-out bureaucrat whose capacity for moral reasoning has been eroded by long service to an amoral system.

Mark Trafford

Mark, Sarah’s banker husband, embodies a comfortable, conformist vision of success that becomes increasingly untenable as the story progresses. At first he seems merely self-absorbed and mildly patronising: he dismisses Sarah’s frustrations, presses her about having a child on his timetable, and treats money as both a practical concern and an instrument of control, as seen in Sarah’s guilt over spending on Joe without telling him.

Their arguments show how little he understands the depth of her dissatisfaction; he minimises her sense of purpose around Dinah, prefers not to look too closely at anything that might disturb his orderly career, and uses charm and flowers to plaster over real fractures. As the conspiracy thickens, Mark’s moral cowardice comes into clearer focus.

He is willing to let Sarah be painted as a drug user, does not fight hard for Joe’s reputation, and by the time Amos pressures him after Rufus’s death, he is a man who can be silently “managed” by threats to his job and freedom. Sarah seeing him kiss another woman on the station platform crystallises what has been true all along: his loyalty is to his own comfort and status rather than to her.

In a novel about betrayal by institutions, Mark represents betrayal on a more intimate scale, a husband who prefers complicity and denial to standing beside his wife in a dangerous truth.

Gerard Inchon

Gerard Inchon is the charismatic, manipulative businessman whose wealth and self-confidence allow him to play social ringmaster. At Sarah’s dinner party, he revels in needling her, diagnosing her Bored Housewife Syndrome, mocking Rufus, and speaking with chilling detachment about war and nuclear weapons as business opportunities.

His view of the looming Middle Eastern conflict is stripped of any human concern; he talks in terms of markets, profit and political leverage, revealing an ideology where ruthlessness is a virtue. In the Cotswolds cottage, his curated rusticity and careful performance as genial host show how adept he is at constructing images, whether of a country retreat or of himself as a self-made survivor of a harsh upbringing.

Sarah’s drunken suspicion that he might have planted the bomb at the Singletons’ house plays into the book’s pattern of mistrust toward those who wield economic power, even if the text never confirms a direct operational link. More concretely, his late-night hints that she should “get out while she can” and that she does not know who her friends are suggest he is more tuned in to the darker workings of the world than he pretends.

Gerard occupies the shadowy border where finance, politics and covert operations may overlap, a figure who may not get his hands dirty directly but thrives in a system that allows atrocities as long as they are good for business.

Paula Inchon

Paula, Gerard’s wife, exemplifies the role of the trophy spouse in the world the novel skewers. She is impeccably dressed, bored, and largely decorative, someone who appears in carefully staged photographs at charity events and in tastefully designed rooms but whose inner life remains mostly offstage.

Her boredom at the country weekend, her absence from serious conversations, and her passivity in the face of Gerard’s manipulations highlight how women in this social tier are often expected to be part of the décor. At the same time, the duplication of the bedroom from London to the Cotswolds hints at Gerard’s control over every aspect of their life together, raising the question of how much Paula is complicit and how much she is another person trapped in his curated world.

She functions less as an individual than as a symbol: a reminder that surfaces can look serene while deeply compromised men move money and influence behind the scenes.

Wigwam

Wigwam, Sarah’s old friend, initially offers a contrasting lifestyle to Sarah’s middle-class domesticity. Eccentric, slightly chaotic, partnered with the apparently gentle Rufus, she represents a kind of bohemian escape route: the friend who lives differently, whose house and manners do not align with Mark’s bank-approved world.

Wigwam’s presence at the dinner party and later visits to Sarah’s home give Sarah moments of solidarity and relief. That makes the later revelation of Rufus’s true nature even more brutal.

When Rufus sneers that he has “dealt with” Wigwam, the implication that she has been murdered lands not only as a plot shock but as a symbolic extinguishing of an alternative way of living. Wigwam’s likely offstage death underscores how far the conspiracy’s reach extends into ordinary lives and how the collateral damage of covert operations includes not just anonymous civilians but the people who briefly offer warmth and difference to the protagonist.

Dinah Singleton

Dinah is at once a character and an emblem. As a four-year-old child, she has very little direct voice in the narrative; we see her through flashes of red overalls and yellow jelly shoes, through Sarah’s obsessive mental images, through the hospital that refuses to talk about her, through the island bedroom decorated with drawings and the big blue teddy bear, and finally in the chapel and the 2CV where she waits with eerie calm.

Dinah is the moral centre of the story’s quest: her disappearance is the puzzle that awakens Sarah, the bait used by Amos and Howard to draw out Downey, and the symbol of innocence exploited by men who think nothing of blowing up a family home. The revelation that she is biologically Thomas Singleton’s child but emotionally claimed by Downey deepens that symbolism; she is literally the product of the desert programme’s survivors, the next generation that those experiments were supposed to protect but instead have endangered.

Dinah’s stoic behaviour, such as her simple pointing from the teddy bear to Amos and calling him “that man again,” gives her a kind of quiet power. She sees enough to connect faces, yet she is still too young to understand the stakes.

The novel ends with her in Sarah’s arms, suggesting a fragile hope that at least one child might escape the cycle of secrecy and violence that destroyed her parents.

Thomas Singleton

Thomas Singleton is dead long before the main events of Down Cemetery Road, yet his presence saturates the story. Officially, he died in a helicopter crash off Cyprus years earlier; in reality, he was part of the secret desert programme with Michael Downey, declared dead on paper so he could be used in experiments that would never be admitted in public.

When the Oxford explosion reveals that Thomas has just been killed again, his double-death becomes the smoking gun Joe follows and the basis of the letter he sends to the Ministry. In Downey’s recollections, Thomas is the one who maims a teenage conscript to force surrender, suggesting a man hardened by war and willing to do ugly things for a perceived greater good.

Later, when they discover their official status as dead men, Thomas realises before Downey how deep the betrayal runs and how impossible it will be to return to normal life. Dinah’s existence as his child, raised in a house that becomes ground zero for a covert operation, shows how thoroughly the system has infiltrated and destroyed his family.

Thomas embodies the tragic figure of a soldier who believes he is serving his country and is instead sacrificed twice: first in the desert, then in the bombing of his home.

Maddie Singleton

Maddie Singleton, Thomas’s wife and Dinah’s mother, is another victim who never gets to speak for herself. To the community she is the soldier’s widow who lost her husband in a foreign helicopter crash and then, years later, dies in an explosion that collapses her riverside house into the water.

Wigwam’s account of Maddie’s life—living alone with Dinah, managing grief, maintaining a fragile domestic routine—gives her a sketchy outline that the blast violently erases. Maddie’s death makes the horror of the operation tangible for Sarah: this is not an abstract national security issue but the obliteration of a woman she might have known.

The fact that Dinah survives upstairs, shielded by a wardrobe, heightens the pathos. Maddie represents the unseen spouses of soldiers whose lives are shaped and sometimes destroyed by decisions taken in distant offices by men like C, Howard and the Cranes.

“C”

The senior official referred to only as “C” occupies the top tier of the secret hierarchy. He is furious about the Singleton explosion not because civilians died or a child is missing, but because the operation was messy and risked exposure.

In his conversation with Howard, he demands that Downey be silenced and that the scandal never see daylight. C embodies the cold logic of institutional self-preservation.

He does not dirty his hands with fieldwork, yet his insistence on deniability and his willingness to sanction further cover-ups make him morally central to the catastrophe. By keeping him nameless, the book suggests that he could be any number of faceless senior figures; what matters is not personal quirks but the role itself, a position whose primary function is to ensure that the system survives even when it has committed atrocities.

Jed

Jed, the boatman who takes Sarah and Zoë to the island, is a minor but telling character. He represents the practical, working-world outsider who has inadvertently brushed up against covert operations.

He knows helicopters have landed on the island; he senses that the place is “popular” in ways that are not purely recreational. Yet he still treats the job as a transaction, insisting his boat is safe, haggling over the fee, and finally handing back Zoë’s cheque as a form of mutual insurance—if something happens to them, people will ask questions.

Jed’s awareness that names, receipts and visible traces can provide a measure of protection echoes Zoë’s own strategic thinking. By the end, when Sarah and Zoë tell him to forget they were ever there, he becomes a quiet witness to the fact that strange, dangerous things happen on the edges of ordinary coastal life, and that survival sometimes means deliberately not knowing too much.

Brian, Paul and Deedee

The trio on the island—Brian, Paul and Deedee—are minor characters who illustrate how the secret state co-opts and discards ordinary people. Brian fakes his death outside the farmhouse, lying face up with an apple in his hand, playing the role of a corpse to deter further investigation.

Paul’s body in the kitchen, shot through the chest, is part of the same grisly tableau, later revealed to be a staged scene designed to make Michael think everyone is already dead or to frighten him away. Deedee, badly beaten and bleeding in Dinah’s decorated room, overacts her “death” because she has been coerced into playing a part.

The revelation that Michael simply walked in and took Dinah, and that Deedee later genuinely died from her injuries, underlines how little regard Howard and his colleagues have for the lives they manipulate. These three are not high-level operatives; they are caretakers, hired help, small-time accomplices who nevertheless end up dead or traumatised.

Their fate shows that in a system built on secrecy, even those on the lowest rung can be forced into roles that destroy them.

David Keller

David Keller is a victim whose significance lies in his absence. A pharmaceutical rep travelling the roads, he is murdered offstage by Amos Crane, who then appropriates his car and identity.

When Sarah and Zoë accept a lift from “David,” the scene reads like an apparently lucky break, but the reader knows they are sitting feet away from a ghost. Keller’s murder demonstrates the casual way Amos removes obstacles: a random man in the wrong place becomes a convenient skin suit, his life erased to smooth the path to the chapel confrontation.

The contrast between Keller’s mundane job and the deadly game being played using his name reinforces the theme that ordinary lives can be co-opted and erased without ever appearing in the official story.

Inspector Ruskin

Inspector Ruskin is the face of the regular police within the novel, and his behaviour shows how easily official structures can be bent to serve hidden agendas. When Sarah calls to retract her statement about Joe dealing drugs, he responds not with concern for the truth but with threats about wasting police time and possible charges.

His goal is not justice but compliance; he wants the inconvenient witness to shut up and accept the narrative already written. Ruskin’s bullying tactics mirror Howard’s more sophisticated manipulation, suggesting a continuum from everyday institutional pressure to the extreme coercion of the secret service.

For Sarah, standing up to Ruskin is one of the first moments where she chooses to risk legal trouble rather than collude in a lie, a small but crucial step in her moral evolution.

Themes

State Power, Secrecy, and the Disposable Citizen

State authority in Down Cemetery Road operates like a hidden machine that decides who counts as real and who can be erased from the record. The Singleton explosion is not an accidental tragedy but the surface sign of an operation run by men like Amos Crane and Howard, whose careers depend on keeping certain truths buried.

Thomas Singleton and Michael Downey have officially “died” once already in a helicopter crash off Cyprus; when the bomb kills the Singletons again, the system simply rewrites reality a second time. The state’s power here is not only about guns and surveillance; it is about ownership of information—who knows what, whose story is permitted to exist.

Hospital records vanish, police files are sealed, witnesses are leaned on until they retract statements. Even the dead man in the opening hospital scenes is kept in a permanent limbo: restrained, scanned, anaesthetised, never properly informed of where he is or why he’s being held.

Civil institutions that ought to protect citizens—the police, the Ministry, the Army—form a single nervous organism that prioritises “containment” over justice. When Howard tries to bully Sarah with Official Secrets legislation and vague promises of leniency for Mark, he is using the law as a weapon rather than a safeguard.

Yet the book also shows this power as fallible and absurd: Howard loses an arm when the sabotaged shotgun explodes; Amos, the great controller, dies in a small chapel in front of a child. The state can erase lives on paper, but it cannot fully control chance, personal loyalty, or the stubborn persistence of human witnesses.

Through this tension between ruthless capability and unexpected vulnerability, Down Cemetery Road questions the moral claim of governments to act in secret “for the greater good,” and suggests that once secrecy becomes a habit, citizens become expendable assets rather than people.

War, Trauma, and the Afterlife of Violence

Combat does not stop when soldiers are shipped home in Down Cemetery Road; it simply changes shape. Michael Downey’s desert memories of boy soldiers melting under helicopter fire refuse to remain buried inside his head.

They seep into the narrative so strongly that the reader almost shares the disorientation: hospital scans blur with desert nights, present danger echoes past atrocities. The desert training programme that Michael and Thomas Singleton endured adds a further layer of psychological damage.

They are repeatedly sprayed with an unknown substance, told they are already dead, and used in operations where “targets” turn out to be terrified teenage conscripts. Violence is not only physical here; it is a systematic unpicking of identity, turning men into tools who can later be written off as convenient corpses.

The burned man’s confusion at the start and Michael’s terminal illness suggest that whatever the army used on them keeps killing them slowly, long after official hostilities ended. Trauma becomes a kind of internal exile: Michael cannot live openly, cannot settle, cannot trust authority, yet he is still bound by loyalty to his friend’s child, Dinah.

Even the civilian characters are touched by war’s aftershocks. Sarah’s life in Oxford seems domestically safe, but the explosion on the riverbank demonstrates how quickly military decisions made in distant deserts spill into ordinary streets.

The new Middle Eastern war playing on hotel television screens while Michael recounts his past underlines that the cycle continues: fresh conflicts are already generating the next generation of damaged soldiers and secret operations. The book suggests that the true cost of war is not captured in casualty numbers or victory speeches; it continues through nightmares, secret illnesses, and the quiet, desperate acts of people like Michael who try to salvage one small piece of innocence—here, a little girl—from the wreckage created in the name of strategy.

Boredom, Domestic Stagnation, and the Search for Purpose

Sarah’s life at the start of Down Cemetery Road might seem almost cosy from the outside: a South Oxford home, a banker husband, dinner parties with successful friends. Yet her inner landscape is defined by restlessness and dissatisfaction.

Gerard sneeringly labels it “Bored Housewife Syndrome,” but the book treats her frustration as something more serious than a lazy cliché. Sarah’s stalled publishing career, her uncomfortable dependence on Mark’s income, and their simmering disagreement about having a child create a sense that her life has been placed in a holding pattern decided by others.

The explosion next door is not just a plot trigger; it is an emotional shock that reveals how thin her domestic arrangements really are. Instead of being content to watch events from her window and accept the official line, she fixates on Dinah’s fate and on the missing father, refusing to let the story end at the edge of her garden.

Hiring Joe with money she hides from Mark is an act of rebellion but also of self-definition: she is choosing a project that matters to her, not to anyone else. As her investigation draws her into contact with intelligence officers, assassins, and traumatised veterans, it also exposes the moral flimsiness of the world she previously inhabited.

Gerard’s expensive cottage, the boutique rustic décor, the dinner-table banter about nuclear war and profit all come to feel like a gaudy shell over something rotten. By the time Mark’s infidelity is revealed on the train platform, Sarah’s desire for a conventional, polished life has already been eroded.

Her decision to continue searching for Dinah, to stand up to the police, to face down men with guns, springs from the same soil as her early boredom; the difference is that she has found something worth risking herself for. The book suggests that domestic stagnation is not simply a private misery; it can also be the starting point for unexpected courage, once a person refuses to let their life be managed entirely by others’ expectations.

Moral Ambiguity, Complicity, and Corruption

Few characters in Down Cemetery Road can be neatly labelled as purely good or purely evil; instead, the narrative is filled with people whose choices are shaped by fear, ambition, loyalty, or exhaustion. Government operatives such as Howard and Amos justify dubious acts by appealing to national security, but their behaviour frequently reveals motives far less noble: career survival, personal rivalry, the desire to maintain control.

Howard tries to make himself sound like a weary guardian of democracy, but he also lies to Sarah, threatens her, and participates in schemes that involve bombing a family home and kidnapping a child. Amos is even more chilling, treating lives as pieces on a board; yet his fierce protectiveness of his brother Axel shows a twisted strain of loyalty that complicates a simple villain label.

On the other side, Michael Downey is both rescuer and perpetrator. He once maimed a teenage conscript to force a surrender and participated in the desert operations that produced the boy soldiers’ suffering, yet he later dedicates himself to protecting Dinah, and the book implies that guilt plays a powerful role in this transformation.

Sarah herself is far from spotless. She lies to her husband about money, snoops in Gerard’s private files, and, under pressure, signs a false statement accusing Joe of dealing drugs, a betrayal that contributes to his death.

Her later attempt to retract the statement shows conscience, but the damage is already done. Even seemingly minor figures like Jed and the island inhabitants participate in staged scenes and manipulations, their cooperation bought or coerced.

This dense layering of dubious decisions suggests that corruption is not a single dramatic event but a chain of compromises, each one making the next easier. The book does not excuse atrocities, but it shows how ordinary people can be drawn into them through a mixture of self-protection, institutional loyalty, and the slow erosion of their ability to say no.

At the same time, it allows room for redemption: Sarah’s refusal to be intimidated, Zoë’s determination to clear Joe’s name, and Michael’s rescue of Dinah represent attempts to pull away from that web, even if they can never fully wash their hands of what has happened.

Truth, Memory, and the Struggle for a Coherent Story

Throughout Down Cemetery Road, the fight is not only over people and documents but over which version of events will be accepted as real. Official records declare Thomas Singleton dead in a helicopter crash and then again in the house explosion; Michael Downey is also reported dead in the past, and yet he keeps reappearing, alive and inconvenient.

Joe’s work as a private investigator revolves around teasing out hidden narratives—who cheated, who lied, who disappeared a child—but when the intelligence services intervene, even his careful gathering of facts can be wiped away. His file on Sarah vanishes from the office; a police contact who spoke too freely tries to erase his own loose talk by returning the bribe and invoking a clampdown.

Sarah’s own memory is constantly under attack as well. Heavy tranquiliser use leaves her groggy and doubting her perceptions, while the authorities encourage her to see herself as unstable, hysterical, or selfish.

When news reports ignore Dinah’s disappearance and the newspaper coverage dwindles, Sarah begins to question her instincts: perhaps the girl is safe and she is simply obsessive. The novel shows how easy it is for official silence to make people mistrust their own recollections.

On the other hand, memory also becomes an act of resistance. Sarah’s refusal to forget the image of Dinah in red overalls pushes her to keep asking questions.

Zoë’s insistence that Joe never dealt drugs challenges the police narrative and eventually forces Sarah to confront her own complicity. Michael’s memories of the desert operation are the opposite of the army’s official story; he knows the “bad guys” were frightened kids, not hardened terrorists, and this knowledge drives his distrust.

By the end, the recovery of Dinah and the exposure of some of the truth about the desert programme do not result in tidy legal accountability, but they do create a shared understanding between Sarah, Zoë, and Michael that counters the state’s false version. The book suggests that maintaining a coherent, honest story about what has happened may be the only form of justice available when institutions have the power to erase or rewrite the official record.

Female Agency, Friendship, and Resistance

Women in Down Cemetery Road are often underestimated, sidelined, or openly mocked, yet they gradually become the driving force of the plot. Sarah begins as the person at the dinner table whose opinions are brushed aside by Gerard and Mark, treated as a sentimental bystander to “real” conversations about war and business.

Her friend Wigwam is seen as eccentric; Rufus presents as the strong, decisive partner. Zoë initially appears in the background as the widow of a more “important” man, Joe, whose professional life and investigative skills supposedly made him the central player.

Over time, this perception flips. Joe is dead; Gerard’s power proves hollow; Mark is revealed as weak and compromised.

Meanwhile, Sarah and Zoë push the story forward through stubbornness and mutual support. Zoë’s confrontation at Sarah’s house—accusing her of lying, forcing her to retract her statement—is not just about defending Joe’s reputation but about refusing to let the narrative be controlled by bullying men in suits.

When Sarah and Zoë travel together to the island, they confront corpses, darkness, and the possibility of their own disappearance. Their decision to go down into the basement corridor despite every instinct screaming at them not to shows a kind of courage that is both practical and emotional.

They do not see themselves as action heroes; they are scared and occasionally nauseous, but they keep moving. Even earlier female figures, like Maddie Singleton and the dying carer Deedee, underscore how easily women are used as collateral in operations they never chose.

Yet the ending shifts the focus to a small, resilient triad: Sarah, Zoë, and Dinah. Sarah’s act of lifting Dinah into her arms and walking out of the woods towards Zoë marks a new kind of alliance, built on shared risk and shared knowledge rather than on romantic or economic dependency.

The book’s power lies in how it takes women who are dismissed as bored, fragile, or peripheral and places them at the centre of resistance against both domestic betrayal and state violence.

Performance, Deception, and Staged Realities

Acts of performance occur again and again in Down Cemetery Road, blurring the line between authenticity and role-playing. The “guerrilla theatre” shooting in the café is the most explicit example: an actor appears to be gunned down at the next table, shocking Sarah and Joe, only to leap up for a bow.

This incident trains both characters—and the reader—to question surface appearances. Later, the intelligence world applies a much darker version of the same principle.

On the island, a man lies “dead” with an apple in his hand; another corpse in the kitchen has been positioned to suggest a savage execution. Deedee stages a drawn-out death scene after being beaten into compliance, turning her real suffering into a controlled performance designed to mislead Michael.

Brian pretends to be a corpse so convincingly that even hardened operatives move past him. These fakes are not harmless theatre; they are tools in a larger effort to manipulate reactions and misdirect investigation.

The intelligence community itself operates as a producer of performances. Official statements, carefully leaked stories, and staged accidents like the Singleton explosion all function as narratives aimed at specific audiences: the press, internal superiors, the general public.

Even Gerard’s persona as the jovial, crude businessman is a kind of performance, masking his history and his connections. On a smaller scale, domestic life involves its own stagecraft.

Mark plays the role of concerned husband while hiding infidelity and complicity; Sarah plays the role of serene hostess while seething internally. The book suggests that survival in such a world requires learning to read these performances and, sometimes, to stage counter-performances of one’s own.

Zoë’s use of Joe’s advice about leaving a chamber empty, and Sarah’s apparent acquiescence to Howard’s demands followed by the sabotaged shotgun, are both examples of turning the logic of performance back on those who usually direct it. In this landscape, being able to distinguish show from substance becomes a vital skill, and failure to do so can be fatal.

Children, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Protection

At the emotional core of Down Cemetery Road stands a child who spends much of the book offstage. Dinah Singleton is initially little more than an image in Sarah’s mind—red overalls, yellow jelly shoes, a tiny survivor pulled from a collapsed house.

Precisely because she is small, largely silent, and apparently powerless, she becomes the focal point of competing agendas. For Sarah, Dinah represents a chance to do something meaningful with her life, a living argument against passive acceptance of official stories.

For the intelligence services, Dinah is bait, a means of drawing out Michael Downey and then justifying further clandestine action. The book’s most disturbing moments come when it becomes clear that the state is perfectly willing to risk or exploit a child’s safety to secure its objectives; the teddy bear tracking device is both grotesquely cute and chilling.

In the background loom the boy soldiers of Michael’s desert memories, teenagers snatched from their own contexts and used as live targets. The moral outrage of that earlier operation spills into the present through Michael’s determination that Dinah will not be treated in the same way.

The ethics of protection are constantly tested. Mark, who wants a child in the abstract, fails to protect his own marriage and shows no appetite for confronting the dangers that have engulfed his neighbour’s daughter.

Sarah, who has resisted motherhood partly out of fear and uncertainty, ends up assuming a fiercely protective role towards Dinah, risking legal trouble and physical harm. Michael, whose hands are far from clean, shows a stubborn commitment to the girl that contrasts sharply with the cool calculations of the officials who claim to act for the country.

By the time Sarah lifts Dinah into her arms near the chapel, the book has made it clear that genuine protection cannot be outsourced to systems that treat people as data points. It must be enacted by individuals willing to see a child not as leverage or symbol, but as a person whose safety matters more than secrecy or reputation.

Class, Money, and Unequal Power

Money flows quietly underneath the plot of Down Cemetery Road, shaping whose voices carry weight and whose concerns are ignored. Gerard Inchon’s wealth allows him to host weekends in a Cotswolds cottage artfully designed to look rustic while actually being the product of expensive professional labour.

His charity photographs, framed in his private study, signal how the rich can purchase public virtue while making ruthless decisions in business and politics. Gerard’s flippant talk about war as an opportunity and his contempt for people like Rufus emphasise his belief that the world is a competitive arena in which only the tough deserve to win.

Mark, as a banker servicing clients like Gerard, occupies a lower rung of the same hierarchy, anxious to stay in his patron’s good graces, willing to look away from ethical questions as long as his career and lifestyle remain intact. Sarah’s financial position is more precarious.

Her shock at Joe’s day rate, her guilt about spending household money on the investigation without telling Mark, and her dependence on tranquilizers prescribed under his name all show how economic vulnerability can narrow a person’s options. The intelligence operatives occupy another zone of privilege: they may not be rich in a conventional sense, but they sit close to the levers of power, able to threaten people with Official Secrets charges, to erase records, and to shape media coverage.

Ordinary citizens—Maddie Singleton, Jed the boatman, hospital staff, local police—are pushed around by both moneyed elites and secretive bureaucrats. When Sarah threatens to go to the press, it is one of the few tools an ordinary person has to counter these forces, yet even that tool is limited by editors’ attention spans and the risk of legal threats.

The novel suggests that class and money do not simply determine comfort levels; they decide whose fear counts and whose outrage can be safely ignored. By tracing how wealth, career considerations, and institutional status interact, the book highlights the uneven distribution of risk: some people are protected by layers of privilege, while others—like Dinah and Michael—are left to face the consequences of decisions made in distant boardrooms and sealed offices.